Browse in the Library:

and subscribe to our social channels for news and music updates:

Search Posts by Categories:

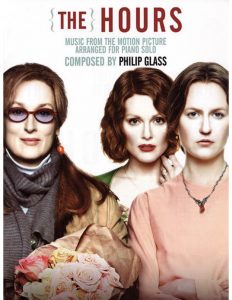

Philip Glass – The Hours – Piano solo (with sheet music)

Sheet Music download here.

Philip Glass Biography

Born on January 31, 1937, in Baltimore, MD; married four times; children: three. Education: Graduated from the University of Chicago, 1956; graduated from the Juilliard School of Music.

The American composer Philip Glass continues to have a tremendous impact on contemporary music. His brand of music is often described, much to his chagrin, as minimalism. Glass’s music and his approach to creating it are thoroughly modern, even revolutionary, making him one of the most provocative, commercially successful, and controversial composers of his generation.

“Glass’s music can be found not only at the opera where he reigns supreme as American’s most successful living composer, but at the ballet, on television, in symphony halls, films, jazz clubs, and even the occasional sports stadium,” wrote William Duckworth in Talking Music.

Philip Glass was born on January 31, 1937, in Baltimore, Maryland. His interest in music developed from an early age, thanks to the eclectic tastes of his father who owned a radio repair shop/record store. Glass heard everything from the extremely popular Elvis Presley records to obscure composers such as Foote and Gottschalk. His father typically brought home the 78 RPM records that did not sell. The biggest impressions on Glass during this period were made by Schoenberg, Anton Webern, and Berg.

Glass began playing violin at the age of six, flute by eight. The bright young man advanced quickly as a scholar and musician. “Musicians have something like a calling, a religious calling,” he told Duckworth. “It’s a vocation. I think it happens before we know it’s going to happen. At a certain point you realize that’s the only think you can take seriously.”

He entered a program for gifted youth at University of Chicago at the age of 15. He quit flute about this same time because he says he knew he could not make a career of it. “Had I not been ambitious, I would not have noticed that it was a limited repertoire. I would have been happy to play the Telemann, Vivaldi, the few Mozart pieces, and the handful of modern works, which of course I tried.” In addition to academic subjects, he studied musicology on his own, concentrating on Charles Ives, Webern, and William Schuman. He also began studying piano with Marcus Raskin.

After receiving a bachelor of arts degree in 1956 at the age of 19, he entered the Juilliard School of Music in New York City in 1958 and pursued composition studies with William Bergsma and Vincent Persichetti for five years. (He had mistakenly thought he would be able to study with Schuman, who was the head of the school at the time and did not teach.)

He continued to explore Ives’s music as well as that of Aaron Copland. Glass also studied with Steve Reich and, later, Darius Milhaud. He served as a composer-in-residence in Philadelphia through a Ford Foundation Grant. During those years alone, he had written 20 pieces and had been the recipient of numerous awards, including a Broadcast Music Industry Award (1960), the Lado Prize (1961), two Benjamin Awards (1961, 1962), and a Young Composers’ Award (1964).

Despite these achievements, Glass increasingly felt that his compositional style, based on 12-tone compositional theory and advanced rhythmic and harmonic forms, was no longer a meaningful. “My twelve-tone period was over by the time I was nineteen, for better or worse,” he told Duckworth. To better realize the music he wanted to created, he went Paris in 1964 to study composition with Nadia Boulanger on a Fulbright Fellowship.

He was looking to her to provide him with the musical technique he thought he needed. His studies were focused on counterpoint, solfege, and composition analysis. “One standard exercise of Boulanger’s was that from any note you had to sing all the inversions of all the cadences in every key,” Glass explained to Duckworth. “It takes about ten or twelve minutes to do, and you go through about thirty or forty formulae. So you become a technician in a certain way. Most Americans don’t have that.”

Reliance on Cyclic Rhythm

Lessons with this famous teacher had less of an impact on Glass than did his exposure to non-Western music. In some respects, Glass notes, it was as if he had discarded everything she taught him. It was while in Paris that he began his long association with Mabou Mines, an experimental theatre company for which he composed music. Outside the theatre, his music was ignored and even reviled. It was this–including physical fights sparked during concerts–that would eventually prompt him to return to the United States.

Glass traveled extensively through India, Tibet, and North Africa, and in 1965 he became a working assistant to the virtuoso sitar player, Ravi Shankar. Through notating his music for Western musicians and studying tabla with the well known Indian percussionist, Allah Rakha, Glass gained an understanding of the modular-form style of Indian music. Shortly thereafter, he completely rejected his earlier compositional style and began to rely solely on the Eastern principle of cyclic rhythm to organize his pieces.

Harmony and modulation were added later, but these typically consisted only of a few static chords. It was also through watching Shankar, that Glass realized he could indeed make a career as a composer-performer. Before 1966 Glass had composed 80 pieces. Now they all seemed irrelevant. He essentially started anew.

After returning from Europe in 1967 the composer organized the Philip Glass Ensemble, a seven-member group consisting of three electric keyboard players and three wind players with one sound engineer. The ensemble made its debut in New York on April 13, 1968, and embarked on the first of several European tours the following year. Notable works from this period include Pieces in the Shape of a Square (1968), Music in Similar Motion (1969), Music for Voices (1972), Music in Twelve Parts (1971-1974), and Music with Changing Parts (1971), a double album and the first release by Glass’s Chatham Records.

Entered Uncharted Musical Territory

Glass’ reputation as a serious composer suffered during this period, in part because he was not an academic composer. Foundations supporting new music compositions snubbed him. Through the early years of the ensemble, Glass worked temporary day jobs–as a crane operator, furniture mover, plumber and taxi driver–to support the group. He wanted to be self-sufficient, independent–“to put myself in a position where I could create what I wanted without having to answer to a council of elders about whether I was a serious composer,” he told Smithsonian. He would continue to work odd day jobs until 1978 when the combination of a grant and a commission from the Netherlands Opera freed him to fully concentrate on composition.

Glass controlled his music from its creation, including securing the copyright for it, then allowing only the ensemble to play and record it. “I felt that if I had a monopoly on the music, that as the music became known there would be more work for the ensemble,” he told Duckworth. “So for the next eleven years, the only people who played my music was the ensemble.”

It was this unique approach to the economics of music that also set Glass apart from his peers. “I figured that if I could get the publishing company working, then I wouldn’t have to work again. And it turned out to be true. In fact, you can make a living and you can do the music that you want; it takes a combination of a lot of different skills. Don’t forget I began working in a record store when I was a kid. The first thing I knew about music was that you sold it; in other words, people paid for it.”

Slowly, Glass was creating a name for himself. The appearance of the ensemble at the Royal College of Art in London in 1970 drew support for his work. In 1974 the first parts of Music in Twelve Parts were released on Virgin Records, a progressive rock label, thereby increasing his exposure to the popular music audience. Glass soon counted such popular performers as David Bowie and Brian Eno among his fans, and his influence could be heard in the rock music of Tangerine Dream and Pink Floyd.

His ability to appeal to numerous musical factions caused him to be described as a “crossover” phenomenon. Indeed, according to David Ewen, he is the only composer ever to have received standing ovations at three varied musical venues such as Carnegie Hall, the Metropolitan Opera House, and the Bottom Line, a venerable New York City music club.

Rejected Minimalism as Accurate Description

Although Glass has been inextricably linked with minimalism, he contends critics are choosing one moment in his career that has long since passed. He has said the most useful description is “chamber music that’s amplified.”

Minimalism, which was en vogue as a compositional style in the late 1960s, emphasized a simplification of the music rather than complex musical structures such as harmony, melody, modulation, and rhythm. “With minimalism, Philip Glass invented a new kind of music that attracted an enormous group of people who had never listened to classical music before and, in some cases, who still only listen to his form of it,” Joseph McLellan, classical music critic emeritus of The Washington Post told Smithsonian in 2003.

“The difficulty is that the word doesn’t describe the music that people are going to hear,” Glass told Duckworth in a late 1990s interview. “I don’t think ‘minimalism’ adequately describes it.” Even in 2003, Glass was protesting “It’s a term invented by journalists. I never liked the word,” he told Smithsonian, “but I liked the attention! … [T]he term became a kind of shorthand for people who were making music that was a radical return to tonality, harmonic simplicity and steady rhythms.”

Glass does indeed utilize repetitive cycles of rhythm, similar to Hindu ragas, which change slowly over long periods of time and are said to produce a trance-like state in some listeners. Certainly his work does fuse together the Eastern musical concepts of space, time, and change with Western musical elements such as diatonic harmony.

Einstein on the Beach

Glass’s alliance with the visual arts prompted a collaboration with Robert Wilson, the painter, architect, and leader in the world of avant-garde theater. Einstein on the Beach, one of Glass’s best known works, was enthusiastically received at its premier in Avignon, France, on July 25, 1976 and was a sellout when performed in New York at the Metropolitan Opera. More a series of “events” than an opera, this full-length stage work explores through dance and movement the same concepts of time and change that Glass investigated through music.

Several characters appear as Einstein, one playing repetitive motifs on a violin; a chorus intones repetitive series of numbers and clichés; dancers and actors perform repetitive actions, such as moving back and forth across the stage in slow motion. Einstein on the Beach has less to do with meaning than concept. “Go to Einstein and enjoy the sights and sounds,” advises Robert Wilson in one interview, “feel the feelings they evoke. Listen to the Pictures.”

Glass followed this work with other theater successes. Satyagraha, commissioned by the city of Rotterdam in 1980, is the ritual embodiment of pacifist spirituality. Based on the life of Gandhi, the opera unfolds as a series of tableaux tracing his early life. The libretto is derived solely from the Bhagavad Gita and is sung in Sanskrit. It is said to be one of Glass’ most lyric works.

Also during this decade, Glass composed The Photographer, a chamber opera based on the life of the early 20th-century inventor Eadweard Muybridge (Amsterdam, 1982) and Akhnaton, his third opera, produced at the Stuttgart Opera in 1984. In addition, Glass began scoring music for films. Most notable among this early work was Koyaanisqatsi, which was successfully received at the New York Film Festival in 1982. It marked the beginning of his collaboration with filmmaker Godfrey Reggio. This was the first in a trilogy of films. The music from this film is an integral part of the ensemble repertoire and continues to frequently be performed by the group live.

That same year, he released Glassworks, his first and one of the first ever digital recordings. It consisted of short pieces and was mixed specifically to take advantage of a new consumer electronic device called The Walkman. Glass continued composing, including numerous works for Mabou Mines, commissions for opera and art installations, and works for choreographers Lucinda Childs, Alvin Ailey, and Jerome Robbins. Glass also collaborated with Wilson on another opera, CIVIL warS: a tree is best measured when it is down, as well as Allen Ginsberg, the beat poet, on Hydrogen Jukebox.

Glass continued his collaborative efforts into the 1990s and beyond. He composed three operas based on films by the late Jean Cocteau, French author and movie director. Orphee, composed by Glass in 1993, followed the soundtrack of the film closely. In La Belle et la Bête (1994), Glass went one step further, stripping the film of its soundtrack and creating a live and carefully synchronized operatic accompaniment that took its place among his finest and most exciting works.

In Les Enfants Terribles (1996) Glass teamed with choreographer Susan Marshall to tell the story through instrumental music and dance rather than singing.

Since 1983 Glass continued to score for films such as Mishima and Thin Blue Line, prompting Billboard to note that “few classical composers can boast a relationship with film music as innovative and dynamic as that of Philip Glass.” He would later add two Academy Award nominations to his long list of accomplishments.

In 1997 Glass composed and recorded a symphony based on the David Bowie album Heroes. One reviewer remarked in New Statesman that Glass needed to be credited his help in taking a giant hammer to the wall traditionally separating classical and rock music. In the same article Glass commented that, “Just as composers of the past have turned to music of their time to fashion new works, the work of Bowie became an inspiration for symphonies of my own.”

Glass released Aguas de Amazonia in 1999 that relied heavily on a Brazilian influence, and he also produced his Symphony No. 2 (Nonesuch) which received much critical praise. He continued creating many new works and made a short solo tour of Europe. Also in 1999, Glass created a soundtrack for the film Dracula, directed by Bela Lugosi.

Glass continued to find interesting collaborative efforts as the year 2000 approached. He and Wilson worked together again with Kleiser-Walczak Construction Company on a unique digital film-performance project. “Monsters of Grace” combined ancient poetry with modern ideas and technologies.

“Monsters of Grace combines technology, poetry, animation and music into a meditative 3-D opera,” explained a contributor to ComputorEdge magazine in 1999. “The production, which takes its name from Shakepeare’s Hamlet, uses computer animated film rather than live actors, as live musicians perform the score. The production’s film is said to rival Toy Story or A Bug’s Life in its digital complexity and is the longest digital film–probably the longest stereoscopic film–to date.” It was Glass who “suggested using Coleman Barks translations of the mystic poet Rumi for Monsters of Grace lyrics.”

Work Habits Created Prolific Production

Glass works every day. This, he attributes to Boulanger’s influence. He typically works from 6 a.m. until noon; afternoons are devoted to working in the studio. He tries to listen to new works one or two times a week, and sets aside one afternoon each week to speak to people. He also uses sampling to help speed the composition process and has said he is limited only by how much music he can write, which seems to still be prolific.

“If we worked bankers’ hours we’d get nothing done!” he told Mark Prendergast, writing inThe Ambient Century: From Mahler to Trance–The Evolution of Sound in the Electronic Age. That pace continued unabated. He was named a featured composer by the Lincoln Center Festival in 2001. That same year he worked on “Shorts”–scoring short films by Reggio, Peter Greenaway and Atom Egoyan–and mounted “White Raven,” a five-act opera created with Wilson and originally commissioned in 1998 to celebrate Portuguese explorers such as Vasco da Gama.

Yet Glass continued to explore seemingly cosmic ideas about how history, social consciousness, and music are all interwoven in works such as “Galileo Galilei” (2002), and Symphony No. 5: Requiem, Bardo and Nirmanakaya, which “encompasses the history of the world in a little more than 90 minutes,” according to The Washington Times. Some reviewers observed his work has a meditative quality, no doubt linked to his practice of Buddhism.

By 2003, Glass had several more projects on which he was working including his twentieth opera “The Sound of a Voice” with Henry Hwang, and scores for the films including The Hours, which earned him a 2003 Academy Award nomination, and Naqoyqatsi, the final film in the Reggio trilogy. American Record Guide, in a March-April 2003 review said that in this latter soundtrack, that when the music is “yoked with images” the music takes on “a mysterious life.”

He also contributed the score to The Fog of War (2003), a documentary film by Errol Morris about Robert McNamara, former United States Secretary of Defense and was releasing various recordings of his works, including that film’s soundtrack, on his Orange Mountain Music label.

Still, there continued to be detractors. Writing in The New Republic in 2000, John Rockwell, editor of the Arts and Leisure section of The New York Times, took Glass to task for being tired and tedious, writing that his work “has declined in quality, and that decline can be described.” Rockwell contends that since about 1984, Glass lost faith or interest in compositional devices such as repetition and periodization, becoming “too restless, too willing to accommodate conventional taste.” He added that Glass “now panders nervously to his audience in the fear they may be bored. And his pandering undercuts the radical, hypnotic aura of his early music.”

“[A]rtists have a way of surprising, and defeating, their critics,” continued Rockwell. “At least he is still working. He did not quit while he was ahead, or retire early.” There is still no firm opinion as to the legacy Glass will leave. Prendergast observes it is Glass’s “contribution to electronic music that is most undervalued. It was Glass who popularized the early Farfisa portable organs and brought the polyphonic synthesizers of the 1970s into concert halls.”

David Schiff, writing in The Atlantic Monthly in 2001, observed Glass is “probably the only American composer since George Gershwin whose music could work equally well in a cocktail lounge … or a concert hall. The music world has not yet made up is mind whether this is a good thing.”

Philip Glass’s Career

Began playing violin and flute, early childhood; graduated from the University of Chicago, 1956; graduated from Juilliard School of Music in New York City; continued composition studies with Steve Reich, Darius Milhaud, Nadia Boulanger; began creating music for theatre while studying in Paris; worked and studied with Ravi Shankar, 1965-1966; moved back to New York and formed Philip Glass Ensemble, 1967; began prolifically creating pieces including Music with Changing Parts, 1971.

Other notable pieces include the operas Einstein on the Beach, 1976, Satyagraha, 1980, CIVIL warS: a tree is best measured when it is down, 1984; and film music for Koyaanisqatsi, 1982, Mishima and Thin Blue Line; created symphony based on David Bowie’s Heroes, 1997. Various other works include the operas Monsters of Grace, 1999, and Galileo Galilei, 2002; plus scores for the films The Hours, Naqoyqatsi, and The Fog of War, 2003.

Philip Glass’s Awards

Broadcast Music Industry Award, 1960; Lado Prize, 1961; Benjamin Award, 1961, 1962; Ford Foundation grant, 1962; Young Composers’ Award, 1964; Musican of the Year, Musical America, 1985; Golden Globe Award for The Truman Show, 1999.

Famous Works

- Selected discography

- Music in Similar Music/Music in 5ths Chatam Square, 1973.

- Music in 12 Parts Virgin, 1975; rereleased, Nonesuch, 1996.

- North Star Virgin, 1977.

- Einstein on the Beach Atlantic, 1979; rereleased, Elektra, 1993.

- Glassworks CBS Masterworks, 1982.

- Koyaanisqatsi Antilles, 1983.

- Akhnaten Columbia, 1984.

- Satyagraha Columbia, 1985.

- Mishima Nonesuch, 1985.

- Songs From Liquid Days Columbia, 1986.

- Dancepieces Columbia, 1987.

- Powaqqatsi Elektra, 1988.

- Mad Rush; Metamorphosis; Wichita Sutra Vortex CBS Masterworks, 1989.

- 1000 Airplanes on the Roof Alliance, 1989.

- The Thin Blue Line Elektra, 1989; reissued, Orange Mountain Music, 2003.

- Mindwalk 1990.

- Hydrogen Jukebox Elektra, 1993.

- Glassworks Catalyst, 1993.

- Low Symphony Polygram, 1994.

- Music With Changing Parts Elektra, 1994.

- La Belle et la Bête (Beauty and the Beast) Nonesuch, 1995.

- Secret Agent Nonesuch, 1996.

- Heroes Symphony Point, 1997.

- Kundun Elektra, 1997.

- Dracula Elektra, 1999.

- CIVIL warS: a tree is best measured when it is down: ACT V; The Rome Section Nonesuch, 1999.

- Piano Music of Philip Glass Roméo/Qualiton, 2000.

- Songs from Liquid Days Silva Classics, 2000.

- Symphony No. 5: Requiem, Bardo, Nirmanakaya Nonesuch, 2000.

- The Music of Candyman Orange Mountain Music, 2001.

- Music in the Shape of a Square Stradivarius, 2001.

- The Hours: Music from the Motion Picture Nonesuch, 2002.

- Naqoyqatsi (soundtrack), Sony Classical/Sony Music Soundtrax, 2002.

- Etudes for Piano, Vol. I, No. 1-10 Orange Mountain Music, 2003.

- The Fog of War Orange Mountain Music, 2003.