Thelonious Monk’s Harmony, Rhythm, and pianism (Part 4)

Read Part 1 here, Part 2 here and Part 3 here.

Techniques and Events in Texture and Harmony. Download Monk’s sheet music and transcriptions from our Library.

Some layers of events do promote continuity in ISC. The original melody is always present in the uppermost note of Monk’s right hand, albeit with occasional octave displacement and with limited embellishments such as minor changes in rhythm or inserted arpeggios. With the sole exception of m. 3, we can identify downbeats in Monk’s performance by the attacks of new har-monies that mark the corresponding downbeats in the lead sheet. Save for mm. 1, 11, 15, 16, 17, and the extended “measures” “29,30 and 31” these are built from shell voicings in which the root plus the seventh immediately above it are the lowest notes heard. These first-beat events track the series of harmonies, and, remembering the tune, we understand the varying times between them to represent equal durations. They ought to help us entrain a meter but do not, due to slow tempo and rubato. Some measures (such as 2 and 4) contain little or nothing more than one of these events, sustained until the next one.

Seen differently, it is because of the rubato that these first-beat moments interact with others to become reference points on the discontinuous sound-scape. Monk paints them with many refi ned techniques that the ear can distinguish and type. They can be understood in terms of how they are shaped by pianism and texture from one perspective, and as voicings from another.

These techniques of pianism and texture are presented below in ascending order of how much discontinuity and contrast they create:

• Register changes. Monk plays the melody in parallel octaves emphasizing the tune’s sixteen-measure parallel structure at mm. 1-2 and 17-18

(foreshadowed at 15-16) and again nearing the conclusion at mm.28-30.” (Mm. 17, 28, and “30” are doubly marked with added tremolo.) The registral acme and nadir of the whole song are linked via the whole-tone run later in m. “30.”

• Arpeggios (fast and slow). Monk inserts this insouciant cocktail piano flourish at mm. 5, 17, 20, 21, and “29.” He uses triad and seventh-chord collections except at m. 20, where he pointedly avoids the root and fifth in keeping with the voicing on the first beat of the measure. A slow arpeggio on the single tone Bb sets the stage for m. “29.”

• Surfacing an inner voice. Beginning with m. 6 and reemerging in mm. 10, 12, 14, 18 and 22, chromatic lines are brought out during moments of repose in the main melody. Presented fi rst as parallel voicings, the tenor line within them is the most independent, venturing forth alone at mm. 12, 14 and 18.

• Attack-sustain. A signature Monkism is to sharply attack a voicing containing a second, tritone, or seventh, and immediately release one or more tones to leave the rest sustaining. The technique stands out vividly and is closely linked to the voicing of clusters (below). It is fi rst heard at m. 6, where the A–B major ninth stands out, and then at m. 8, where, in the first chord, the sustained G is part of the melody, but in the second chord the sustained Db is an inner voice. In mm. 9 and 11 both tones involved (G and F# ) are part of the melody, whereas in m. 13 both melody and an inner voice tone remain. The sustained A# over Bm7 (a #7 in a minor seventh chord) at m. 27 spotlights this pivotal dissonant note from the original tune. A series of fi ve attack-sustain chords concludes the performance, beginning at m. “31.”

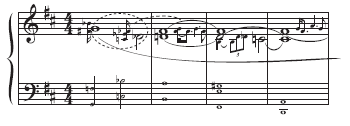

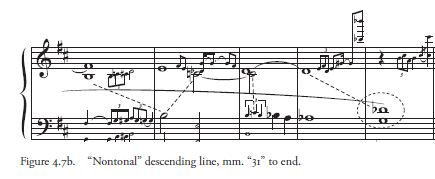

Figure 4.7a illustrates how this technique and the previous one conspire to highlight a special contrapuntal, inner-voice activity. Monk carefully leads the sustained G–Db tritone, introduced one note at a time in m. 8, stepwise down the linear distance of a tritone to the same two tones, inverted and played as a vertical interval in m. 16. We hear the lower of the two voices against ISC ’s melody in the upper until m. 16’s exposed Db , which completes the descent alone just before the melody itself vaults upward. Figure 4.7b is an example of an opposite technique: disjunct, tonally disorienting voice leading. A peculiar “nontonal” descending line, D–A# –F# –Eb –B, is brought out from m. “31” to the end; its bass support, D–B–C–Eb –D, is equally odd. Together they endure a series of pouncing attack-sustain chords. Monk is here singling out important prior moments for our re-consideration, frozen in reverse order and decontextualized.

The bass is silenced just as the A# in the line, and the voicing that introduces it, reconfi rm the significance Monk imputes to m. 27; the next event recalls the third beat of m. 8. The last two chords bring back sustained bass for the b II–I cadence, but with crunching voicings new to the performance, and reserved for its austere conclusion.

The following voicing techniques are ordered by increasing density and dissonance:

• Single tones and silence. Rare moments are reserved for withholding voicings on downbeats. An unadorned root tone played low on the keyboard is the very fi rst sound we hear, creating a powerful solo bass stratum that returns only at m. 28, on the last beat of m. “30,” the

“third beat of m. 32,” and at the very end. The sequence of these unaccompanied roots, E–Bb –A–Eb –D, supports a ii–V–I progression with two inserted tritone substitutions: an essence of jazz harmony. Measure 3, meanwhile, begins silently. Since mm. 3-4 repeat the chords of mm. 1-2, the silence retrospectively calls attention to the bass tone of

m. I, while throwing us off the scent of rhythmic regularity.

• Seventh-chord voicings, some with doublings and omissions. On beats 1 and 3, Monk often uses voicings consisting only of an unadorned

Figure 4.7a. Linear motion by tritone, mm.8-16.

complete seventh chord (mm. 7, 9, 11, 19, 23, 24, and 29, beats 1 and 3). Peterson or Evans might have played these, and their ordinariness gives them a quality of repose. Sometimes Monk omits one or more tones for a stringent sound (mm. 5, 13, 15), and sometimes he omits the third or fifth but doubles the seventh, a biting Monk sonority (mm. 2, 4, 12, 18, 20, 21). The fifth chord in the concluding attack-sustain series omits the seventh of DM7 and adds only the sixth (B).

• Voicings with avoid tones and other dissonance. Monk creates special dissonance by including avoid tones, sometimes omitting essential ones simultaneously. The voicing of A7 at the end m. 3 contains the avoid tone D. The motion over the bar line to DM7 is additionally grating because the seventh of the first voicing, G, moves by a tritone to C# instead of resolving downward, forming a bare octave C# with the melody. The abrasive voicing at m. 8 contains both the seventh (F) and #seventh (F# ) of its minor seventh chord; the latter note rubs up against the root (G). A similar situation obtains at mm. 27, “31, beat 3,” and “32, beat 3.”

• Whole-tone voicings. Monk loved the two whole-tone scales

(CDEF# G# Bb and C# D# FGAB), and a whole-tone voicing consisting of a dominant seventh chord with a fl at fifth. This chord is made up of two tritones a major third apart, and as fi gure 4.7c shows, when transposed by a tritone the pitch content does not change. With this chord it is not a matter of choosing whether to use V7 or its tritone substitution, for the two are now (enharmonically) equivalent. Measures 6, 10 (beat 3), 15, 16, 22 (minus the A# ), 26, and 28 include voicings like this. But even with this preparation, we are not quite ready for the thick whole-tone voicing at m. “30” with its triple C#.

Though we have identifi ed this region as functionally dominant harmony, when we first hear the voicing it is ambiguous: the G–C# tritone is down uncharacteristically low, and there is no root or shell as there is in most other places in ISC. Then, when Monk starts swinging the right hand, a lonely solo line suggesting a C7# harmony, we feel blindsided. This is a more conceptual kind of dissonance. Suspended in rubato, the irony of this nod to conventional jazz at the most tonally and temporally remote moment makes it the climax of the performance. The ensuing whole-tone run jolts us back to reality—Monk’s reality, that is.

Tone clusters. The very first right-hand sound we hear contains a tart cluster of the root, third, seventh, and ninth of the Em7 chord. On the third beat of m. 8, Monk lassoes the root, third, seventh, b ninth, and # ninth of C7, omitting some tones in the parallel return at m. 25.

In all, Monk’s voicings range from pure triads (unique to the final two sounds we hear) to plain seventh chords, attack-sustain events, and thornier constellations, all the way to clusters (m. 1). That these extremes are manifest at the opening and closing of the piece makes the point a bit too neatly: this is a constructed, conscious effort, a dissonance continuum that is a dimensional extension of the idea of the chord change itself. He bobs and weaves across this terrain, tracing an unpredictable path. Few com-posers in any idiom roam so widely in so short a span of time between understood areas of consonance and dissonance, developing timbre as a compositional parameter. That Monk manages this movingly in a standard tune is miraculous.

Monk works some of his signature gestures, such as whole-tone runs, into almost every performance of almost every tune. Then there are certain chords or gestures that he clearly associates with specific songs —accessories, if you will— but that he uses in different locations within the performance. The distinctive chords in mm. “31-32,” for example, are the introduction to his first recording of ISC, on his 1947 Blue Note debut. In both cases they are used once and only once, either as coda or introduction; in other words, for Monk these particular chords and voicings are associated exclusively with ISC, even though they have little to do with the tune’s chord changes. This practice is not necessarily exclusive to Monk, but in combination with the distinctive nature of the gestures themselves, it is a considerable factor in distinguishing his style.

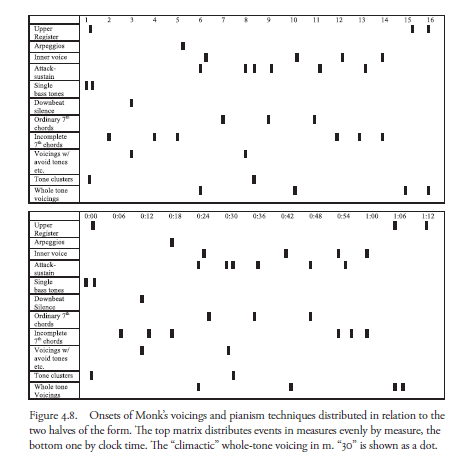

Figure 4.8 illustrates all the aforementioned techniques in two ways: evenly distributed in relation to the thirty-two-measure form, and in a quite different distribution in proportional clock time. Vertical alignments of events are linked to notated beats in the upper matrices and seconds in the lower. In the first pair of matrices, the two representations of mm. 1-16 (0:00 to 1:17) are juxtaposed; the next pair shows mm. 17-32 and the ending. The latter pair of matrices is widened in deference to the extended duration of the passage, though this causes measure width to be different from in the upper pair.

A Note on Monk’s Style.

Tracing Monk’s approach over his complete career and repertoire, one will hear the same melodies and chord voicings in the same contexts, over and over again. In almost every case, he’s “figured out” what to do and simply applies it to each version. Yet his playing sounds spontaneous, and this tossed off , vernacular feel contributes to the music’s deep empathy and all-too-human charm. Pinning this feeling down to a quantifi able list of attributes or abstracting it to an underlying aesthetic is a large task. It may have something to do with “cool,” and perhaps with some notion—to borrow a phrase from a different genre—of “keeping it real.” Making it seem loose, even by calculation, is a way of connecting with the listener, reminding us that behind the sound there is a human deciding what notes to strike (hence the hesitations in ISC, even when multiple takes reveal that Monk knew exactly what chord he would play next), and risking a wrong note every time he strikes them.

We empathize with the feeling of risk and hence take pleasure when he plays the “right wrong notes,” which range from deliberate attack-sustain tones to actual wrong notes —for without the spontaneous risk of these, a “right wrong note” is just a composed-in dissonance. No better demonstration of this can be imagined than the recently released first take of the Riverside ISC, which begins with twelve—twelve!—attempts at an opening arpeggio, all slightly different, all equally “spontaneous” yet calculated, and all unsatisfactory to Monk.

Th ere is a doggedness to Monk’s sui generis formulations—the dissonance continuum and signature gestures—that is hard to wrap one’s mind around. How is it possible that Monk could fi x on a particular, individuated way of playing a three-minute tune in 1947 —distinctive, crystal clear, and packed with formal logic and creativity—and then stick to it for twenty-fi ve years? How did Monk arrive on the scene with such individuality—one can hear the whole-tone scales even on recently unearthed live recordings from the early 1940s—and then maintain it, intact and unchanging, for his entire career? Why do none of his versions change over time? Where did it all come from?

Jazz and World Music, Monk and Personal Musicianship

These unanswerable questions are compounded and enriched by reflecting on jazz as twentieth-century America’s underdog in the realms of musical legitimacy and hybridism. For decades its creative development was hidden in plain sight. It occupied a position with respect to Western music’s institutions and structures of power analogous to the one that many of the contributions to this book (plus its predecessor and other similar writings) occupy with respect to the practice of music analysis generally. Then things changed.

Following decades of exclusion, jazz’s ultimate inclusion in the academic canons of musical value let the cat out of the bag in that world, implicitly affirming openness to all music. As jazz led the way, it gradually penetrated the awareness even of musicians who do not practice it, as other world traditions do today. It is a vehicle for the individual’s quest for self-realization. Its irreducibly hybrid origins offered a paradigm for viewing any music, if not people and social relations. We now have decades’ worth of neohybrids involving jazz and other world music, and generations at home in both jazz and other traditions. If jazz and other African-American musics had not long ago made the case for this evolution, would other traditions have been in a position to do so since? Jazz has made us more musical than we thought we could be.

The problems raised by Monk, however, transcend these issues in a way that we can suggest by recounting a transformational moment we shared. In the late 70s, European art music was just beginning to emerge from its post-war hyper-modernist isolation. At that time, Robert Moore, our composition teacher, taught a course called “American Experimentalists,” in which he cited Monk and composer Steve Reich in the same breath as in a special category among the most important musicians of the century (to date). Coming from professor back then, this link struck us as brazenly counter-hegemonic, and also a cosmic truth. He said it was their indiff erence to traditional virtuosity, combined with intense desire to perform, that forced them to be visionaries and use their minds to invent ways to bend the tradition in their directions.

There are examples of similar outsider-inspired change in other cultures. It is certainly the case that musicianship with the power to transform is more in the mind and spirit than it is in the hands or throat. And this is both unsettling and inspiring because it deflects back to each listener that the necessity of finding a concept, both a general sensibility and a specifi c idea to be developed, that can define the self and contribute to the world. But Monk had already made that clear to the two of us in sheer sound, from the instant we first heard him.

Thelonious Monk With John Coltrane (1961) (Full Album)

Browse in the Library:

and subscribe to our social channels for news and music updates:

Alto Saxophone – Gigi Gryce (# A3, B2)…. Bass – Wilbur Ware (# A1 to B2)…. Drums – Art Blakey (#A3, B2), “Shadow” Wilson (#A1, A2, B1)…. Piano – Thelonious Monk…. Tenor Saxophone – Coleman Hawkins (# A3, B2), John Coltrane…. Trumpet – Ray Copeland (# A3, B2)…. ……………………………………………… A1 Ruby, My Dear 0:00 A2 Trinkle, Tinkle 6:22 A3 Off Minor 13:03 B1 Nutty 18:19 B2 Epistrophy 24:58 B3 Functional 28:09 ……………………………………………… Recorded – New York; 1957-58.