Browse in the Library:

Search Posts by Categories:

Oscar Peterson Plays “Fly Me To The Moon” with sheet music in our Library.

Please, subscribe to our Library. Thank you!

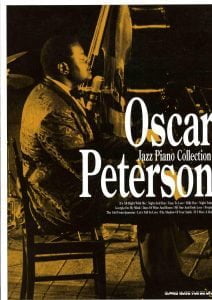

Oscar Peterson

Oscar Emmanuel Peterson, CC, CQ, OOnt, jazz pianist, composer, educator (born 15 August 1925 in Montréal, QC; died 23 December 2007 in Mississauga, ON). Oscar Peterson is one of Canada’s most honoured musicians. He is widely regarded as one of the greatest jazz pianists of all time. He was renowned for his remarkable speed and dexterity, meticulous and ornate technique, and dazzling, swinging style.

He earned the nicknames “the brown bomber of boogie-woogie” and “master of swing.” A prolific recording artist, he typically released several albums a year from the 1950s until his death. He also appeared on more than 200 albums by other artists, including Ella Fitzgerald, Dizzy Gillespie, Billie Holiday and Louis Armstrong, who called him “the man with four hands.” His sensitivity in these supporting roles, as well as his acclaimed compositions such as Canadiana Suite and “Hymn to Freedom,” was overshadowed by his stunning virtuosity as a soloist.

Also a noted jazz educator and advocate for racial equality, Peterson won a Juno Award and eight Grammy Awards, including one for lifetime achievement. The first recipient of the Governor General’s Performing Arts Award for Lifetime Achievement, he was inducted into the Canadian Music Hall of Fame and the International Jazz Hall of Fame. He was also made an Officer and then Companion of the Order of Canada, and an Officer in the Order of Arts and Letters in France, among many other honours.

Childhood, Family and Education

Oscar Peterson was the fourth of five children. He was raised in the poor St. Henri neighbourhood of Montreal, also known as Little Burgundy. His parents hailed from St. Kitts and the British Virgin Islands. (See also Caribbean Canadians.) His mother, Kathleen, was a domestic worker. His father, Daniel, was a boatswain in the Merchant Marines who became a porter with the Canadian Pacific Railway.

A self-taught amateur organist and strict disciplinarian, he led the family band in concerts at churches and community halls. He insisted that all of the Peterson children learn piano and a brass instrument. Each in turn taught the next youngest child.

Oscar began playing trumpet and piano at age five. He focused solely on piano at age eight following a year-long battle with tuberculosis. (The disease claimed the life of his eldest brother, Fred, at age 16.) Oscar’s first instructor was his sister, Daisy. She became a respected piano teacher in Montreal’s Black community. Her later pupils included the jazz musicians Oliver Jones, Joe Sealy and Reg Wilson. Peterson’s brother, Chuck, became a professional trumpet player. His other sister, May, taught piano. She also worked for a time as Oscar’s personal assistant.

Peterson studied piano during his youth and teens with teachers of widely different backgrounds. At the age of 12, he briefly took piano lessons from Louis Hooper, a classically trained Canadian veteran of the Harlem jazz scene of the 1920s. Later, Peterson attended the Conservatoire de musique du Québec à Montréal. At 14, he studied with Paul de Marky, a Hungarian concert pianist in the 19th-century tradition of Franz Liszt. Peterson was also a classmate of trumpet player Maynard Ferguson. They played together in a dance band led by Maynard’s brother, Percy.

Early Career

At age 14, Peterson entered an amateur contest sponsored by radio personality Ken Soble. (He was encouraged to enter by his sister Daisy, who also helped pay for his studies.) Oscar won the $250 first prize. Shortly thereafter, he began his own weekly radio show, Fifteen Minutes Piano Rambling, on the Montreal station CKAC. In 1941, he was featured on CBM’s Rhythm Time. By 1945, he was heard nationally on the CBC’s Light Up and Listen and The Happy Gang.

Peterson’s growing command of the keyboard reflected his classical background. However, the influence of the popular American pianists Nat King Cole, Teddy Wilson and especially his idol, Art Tatum, steered him towards a future in jazz. Even a chronic case of arthritis, which first became apparent in his teens, could not slow his progress. During his teen years, he received offers from Jimmie Lunceford and Count Basie to move to the US and join their bands. His parents felt he was too young and wouldn’t allow it.

Oscar Peterson emerged as a celebrity in Montreal’s music scene in the early 1940s. He dropped out of high school at age 17 to play as a featured soloist in Johnny Holmes’s popular (and otherwise white) dance band from 1943 to 1947. Peterson’s father was skeptical of letting his son leave school to pursue a career in music. He reportedly told Oscar, “If you’re going to go out there and be a piano player, don’t just be another one. Be the best.”

Canada’s First Jazz Star

Peterson made his first recordings for RCA Victor in March 1945. These early releases, notably “I Got Rhythm” and “The Sheik of Araby,” reveal the talent for boogie-woogie that earned him the nickname “the brown bomber of boogie-woogie.” They also reveal the extraordinary technique that would characterize his playing throughout his career. Peterson made sixteen 78s (32 songs in total) for RCA Victor between 1945 and 1949, The last of these suggest the influence of bebop. These songs were compiled on CD by BMG France in 1994; they were repackaged by BMG Canada in 1996 as The Complete Young Oscar Peterson (1945–1949).

The popularity of these records established Peterson as the first jazz star that Canada could truly call its own. His exposure on CBC Radio and his two tours of Western Canada in 1946 also contributed to his growing fame. By 1947, he was headlining Montreal’s Alberta Lounge with his own trio. It consisted of Austin “Ozzie” Roberts on bass and Clarence Jones on drums. (Guitarist Ben Johnson occasionally subbed in for Jones.) The trio was heard on Montreal radio station CFCF in broadcasts from the lounge. The other recorded document of Peterson’s Montreal years is the soundtrack for Norman McLaren’s innovative and award-winning National Film Board short, Begone Dull Care (1949).

Browse in the Library:

By the end of the 1940s, Peterson had all but exhausted the limited jazz market in Canada. Word of his talent had spread to the US. Following a tour to Montreal, Dizzy Gillespie told composer and record producer Leonard Feather, “There’s a pianist up here who’s just too much. You’ve never heard anything like it! We gotta put him in concert.”

However, Feather took no action. Similarly, American jazz impresario and record producer Norman Granz heard about Peterson through Coleman Hawkins and Billy Strayhorn. But Granz also failed to reach out to the Canadian pianist until a 1949 visit to Montreal. Granz was on his way to the airport to leave the city when he heard Peterson playing on the radio from the Alberta Lounge. He told the cab driver to take him there immediately.

American Introduction

Granz became Peterson’s manager. He decided to introduce Peterson to American audiences at a Jazz at the Philharmonic (JATP) performance at New York’s Carnegie Hall on 18 September 1949. The lineup for the show included such jazz greats as Charlie Parker, Buddy Rich, Roy Eldridge and Lester Young. Granz couldn’t secure Peterson a work visa in time for the show. So, he planted him in the audience and brought the six-foot-three, 240-pound 24-year-old onstage as a surprise guest.

Peterson’s performance with bassist Ray Brown caused a sensation. DownBeat magazine wrote that it “stopped the concert dead cold in its tracks.” The appearance was a watershed moment for Peterson. It marked the beginning of an international career of remarkable productivity and distinction.

Career Highlights

Norman Granz became a close friend and was Peterson’s manager until 1988. Under his guidance, Peterson toured with Jazz at the Philharmonic from 1950 to 1952. His bravura performances, both in concert and on record, immediately captured the imagination of the American public. The growth and persistence of Peterson’s popularity was reflected in his first-place standing in the piano category of DownBeat magazine’s readers’ poll 15 times in 23 years: in 1950–54, 1958–63, 1965–67 and 1972. He also won the magazine’s critics’ poll in 1953, in addition to many other such polls.

Peterson made his first American recordings for Granz’s label, Verve, in 1950 with Ray Brown as his bassist. Their version of “Tenderly” was especially popular. In 1951, Peterson formed a trio with Brown (who would be a stalwart of Peterson’s groups for the next 15 years) and drummer Charlie Smith. Smith was soon replaced by the guitarists Irving Ashby (formerly of the Nat King Cole Trio), Barney Kessel and Herb Ellis, who joined in 1953.

The Peterson-Brown-Ellis trio was regarded by many as the best piano-bass-guitar trio of all time. It became renowned for its passionate and spontaneous soloing, as well as its ability to play at breakneck tempos and to tackle complex arrangements.

Peterson toured Europe with JATP in 1952, 1953 and 1954. He returned annually with his trio for many years. They often accompanied the singer Ella Fitzgerald. In 1953, Peterson made the first of many appearances in Japan. In the early 1950s, while playing at a club in Washington, DC, Peterson met his idol, Art Tatum. The two became good friends. Peterson performed at the Montreal, Stratford, Shaw and Vancouver International festivals, and appeared often in Canadian nightclubs. His trio recorded a celebrated LP at Stratford — Oscar Peterson at the Stratford Shakespearean Festival (1956). It also recorded the acclaimed On the Town (1958) at Toronto’s Town Tavern.

Throughout his career, Peterson made Canada his home base. In 1958, he moved from Montreal to Toronto, and later to nearby Mississauga. Also in 1958, Ellis left the trio. In 1959, Peterson changed its composition to piano, bass and drums by adding drummer Ed Thigpen, famous for his sensitivity and meticulous brushwork. The Peterson trio of this period was celebrated for its seemingly telepathic sense of interplay and its virtuosity.

Night Train (1962), recorded with his trio, proved to be one of Peterson’s most commercially successful albums. Canadiana Suite (1964) was one of his most acclaimed. Between 1963 and 1968, he recorded a series of solo albums for MPS called Exclusively for my Friends. Following the departure of Brown and Thigpen in 1965, Peterson added bassist Sam Jones and drummer Louis Hayes. Hayes was replaced in 1967 by Bobby Durham. During the years 1967–71, Peterson recorded for the most part in Villingen, West Germany, for the Saba label (later MPS).

In 1970, Oscar Peterson began to perform solo almost exclusively. He returned to the small ensemble format in 1972 with guitarist Joe Pass and bassist Niels-Henning Ørsted Pedersen. The success of this trio rivaled that of the Peterson-Brown-Ellis group. The band expanded to a quartet in 1974 with the addition of drummer Martin Drew. In the 1970s, Peterson recorded with such artists as Ella Fitzgerald, Count Basie, Roy Eldridge, Dizzy Gillespie and Stéphane Grappelli on many of his own albums for the Pablo label.

The mid-1970s saw Peterson achieve a high degree of critical acclaim and industry recognition. He had four Grammy Award-winning albums: The Trio (1973), The Giants (1974), Oscar Peterson and the Trumpet Kings – Jousts (1974) and Montreux ’77 (1977). He also released live records of concerts in Tokyo, Amsterdam, Paris, London, Tallinn, The Hague and New York.

Despite being afflicted with arthritis since his teens, Peterson maintained a rigorous international touring schedule well into the 1980s. He played and recorded in a duo with pianist Herbie Hancock and made several appearances at the Festival international de jazz de Montreal; these included a concert with the Montreal Symphony Orchestra at the Forum in 1984. He also performed at Ontario Place and Roy Thomson Hall as part of jazz festivals in Toronto.

His album If You Could See Me Now (1983), recorded with the quartet of Pass, Ørsted Pedersen and Drew, won a 1987 Juno Award for Best Jazz Album. However, by decade’s end, his arthritis had become increasingly severe. As a result, he reduced his performance schedule to a matter of weeks each year in Europe, Japan and the US.

In 1990, he reunited with the Brown-Ellis trio, producing several acclaimed albums of their performances at the Blue Note club in New York. Live at the Blue Note (1990) and Saturday Night at the Blue Note (1990) won a total of three Grammy Awards. Last Call at the Blue Note (1990) received a Juno Award nomination.

In 1993, several months after having hip replacement surgery, Peterson had a stroke while performing at the Blue Note. His left side was especially affected. He withdrew from commitments and resumed performing gradually after a two-year recovery. A restricted ability in his left hand became noticeable; it greatly reduced the strong contrapuntal quality that he had always played with. Yet he continued to tour, compose and record. According to broadcaster Ross Porter, “What he was able to achieve, playing with half of what most other pianists had, he was still light years ahead of everyone else.”

Peterson appeared at Carnegie Hall in 1995 and at a tribute to him at New York’s Town Hall in 1996. His album Oscar Peterson Meets Roy Hargrove and Ralph Moore (1996) was nominated for a Juno Award in 1997. He played Massey Hall and Roy Thomson Hall in Toronto, and occasionally at jazz festivals, such as Toronto’s 2001 JVC festival and various European festivals. Also in 2001, he toured Seattle, Los Angeles and San Francisco. By that time, he had completed more than 130 albums under his own name, mainly for the labels Verve (1950–64), MPS (1967–71), Pablo (1972–86) and Telarc (beginning in 1990).

In 2002, Peterson published his memoir, A Jazz Odyssey: The Life of Oscar Peterson. A tribute concert held at Carnegie Hall on 8 June 2007, as part of the Fujitsu Jazz Festival, featured performances by Wynton Marsalis, Marian McPartland, Hank Jones and Clark Terry. Peterson was originally scheduled to appear but bowed out due to frail health. He died of kidney failure in his Mississauga home in December that year.

Compositions

As a composer, Peterson wrote and recorded a variety of his own jazz themes. His popular “Hymn to Freedom” (from Night Train, 1962) became an anthem of the US civil rights movement during the 1960s. Versions of “Hymn to Freedom” were recorded in the 1980s by Oliver Jones and Doug Riley.

Peterson’s most significant and best-known composition was Canadiana Suite (1964). It is an eight-part programmatic survey of Canada’s distinguishing features, including “Wheatland” (the Prairies), “Hogtown Blues” (Toronto) and “Land of the Misty Giants” (the Rocky Mountains). Described by Peterson as “a musical portrait of the Canada I love,” Canadiana Suite was nominated for a Grammy Award as best jazz composition of 1965. It has been arranged for big band by both Phil Nimmons and Ron Collier, and for orchestra by Rick Wilkins, who served on several occasions as Peterson’s orchestrator.

Peterson wrote City Lights (1977), a waltz about the City of Toronto, for the Ballets Jazz de Montreal. He also composed The African Suite (1979), A Royal Wedding Suite (1981, for the wedding of Prince Charles and Princess Diana) and Easter Suite (1984).

He composed and performed works for jazz trio and orchestra on commission from Bach 300 (premiered with the National Arts Centre Orchestra at Toronto’s Roy Thomson Hall in 1984) and for the 1988 Olympic Winter Games in Calgary. His Trail of Dreams: A Canadian Suite, inspired by the Trans Canada Trail, was commissioned by Music 2000 and premiered that year at Roy Thomson Hall.

Peterson’s compositions have been recorded by such jazz greats as Count Basie, Ray Brown, Ray Charles, Ella Fitzgerald, Roy Eldridge, Marian McPartland, Dizzy Gillespie and Milt Jackson. His other works for jazz group over the years included “Hallelujah Time,” “Blues for Big Scotia,” “The Smudge,” “Bossa Beguine,” “A Little Jazz Exercise,” “Tippin’,” “Mississauga Rattler,” “Samba Sensitive” and a variety of informally conceived blues works. Parts of Peterson’s suites (e.g., “Nigerian Marketplace” from African Suite) have been played and recorded as independent pieces.

For film, Peterson wrote and recorded “Blues for Allan Felix,” heard in the Woody Allen comedy Play It Again Sam (1972). He composed scores for the feature film The Silent Partner (1977), which won a Canadian Film Award in 1978, and the documentaries Big North and Fields of Endless Day. The latter was a National Film Board/Ontario Educational Communications Authority-produced history of Black Canadians. His score for the biographical documentary In the Key of Oscar received a Gemini Award in 1993.

Style and Approach

Through his studies with Paul de Marky, Peterson followed in the pianistic tradition of Franz Liszt. Impressionist and late-Romantic influences were also detected in his playing. After a concert in Toronto in 1950, Hugh Thompson observed in the Daily Star, “His version of ‘Tenderly’ leans heavily on Debussy and Ravel in its harmonies, and his ‘Little White Lies’ had definite echoes of Rachmaninoff.”

In jazz, Peterson acknowledged the influence of Art Tatum, Teddy Wilson, Hank Jones and Nat King Cole (whom Peterson resembled especially on the rare occasions he sang). Peterson’s style can be heard as the product of a transitional period in jazz, the 1940s. Even in his later years he moved freely from stride to bebop.

Gene Lees, writing in Maclean’s in 1975, quoted the Argentine composer-pianist Lalo Schifrin as saying, “Oscar is a true romantic in the 19th-century sense, with the addition of the 20th-century Afro-American jazz tradition. He is a top-class virtuoso.” Lees added, “This response is common. Peterson has astounding speed. Only Phineas Newborn and the late Art Tatum, one of his idols and mentors, have equaled him. And he has a power of direct swing that Tatum never equaled.

His ideas are not always original; on a poor night, he falls back on his own highly identifiable phrases of musical vocabulary and some he got from others, such as a curious spinning chromatic figure of Dizzy Gillespie’s. But these alone can be electrifying — the brilliantly clear and perfectly balanced runs, like streams of sparks, the great chords whacked into perfect place in the swing with the left hand that plays tenths effortlessly and could, I suppose, if he wanted, encompass twelfths, the dizzying passages in octaves that utilize a left hand as proficient as the right.”

Criticism and Praise

Paradoxically, Peterson’s greatest strength, his technique, brought him his greatest criticism: that his performances, for all their facility, were an overwhelming mélange of style over substance and lacked emotional warmth. In 1973, Times of London music critic John S. Wilson wrote, “For the last 20 years, Oscar Peterson has been one of the most dazzling exponents of the flying fingers school of piano playing.

His performances have tended to be beautifully executed displays of technique but woefully weak on emotional projection.” The New York Times noted in his obituary that, “many critics found Mr. Peterson more derivative than original, especially early in his career. Some even suggested that his fantastic technique lacked coherence and was almost too much for some listeners to compute.” JazzTimes critic Thomas Conrad described Peterson’s achievements as “more athletic than aesthetic.” He claimed that songs which should have been occasions for self-revelation became, in Peterson’s hands, “elegant, flawless and detached.”

Noted musicologist Max Harrison and New Yorker columnist Whitney Baillett found Peterson’s style to be glib and superficial. No less a figure than Miles Davis criticized Peterson’s ability for interplay, saying that, “nearly everything he plays, he plays with the same degree of force. He leaves no holes for the rhythm section.”

The Toronto Star’s Peter Goddard once observed that, “wowing audiences with flash fingering bothered critics who thought speed was all he had… In the 1950s hailed as ‘the greatest living jazz pianist,’ by 1961 it was an opinion that ‘would not be considered in serious jazz circles,’ snapped British critic Burnett James.”

However, Peterson’s champions typically outnumbered his critics. Duke Ellington nicknamed him “the Maharaja of the keyboard” and said he was “beyond category.” In the early 1990s, esteemed American pianist Hank Jones said, “Oscar Peterson is head and shoulders above any pianist alive today. Oscar is the apex. He is the crowning ruler of all the pianists in the jazz world. No question about it.” Acclaimed pianist Marian McPartland described him as “the finest technician that I have seen,” and pianist and conductor André Previn called him “the best” among jazz pianists.

Following Peterson’s death, the Independent described him as “an explosion of talent” who “could overwhelm any style of jazz piano and… swing harder than any other player. In fact, the best way to define the elusive quality of ‘swing’ might be to use a Peterson performance as an illustration. He had a deep knowledge of jazz history and could play two-fisted stride, or complex and intricate bebop. His timing and imagination also made him one of the great ballad players. He had everything, with only an occasional penchant for rococo decoration to detract from his achievements.”

Influence on Other Pianists

Peterson’s influence on his fellow musicians is difficult to estimate. His extraordinary level of skill made his playing difficult to emulate directly, as did his lack of affiliation with a particular style or idiom. However, he was an early inspiration to many pianists. Herbie Hancock once wrote, “Oscar Peterson redefined swing for modern jazz pianists for the latter half of the 20th century… I consider him the major influence that formed my roots in jazz piano playing. He mastered the balance between technique, hard blues grooving, and tenderness.” Nanaimo, BC, native Diana Krall once called Peterson “the reason I became a jazz pianist. In my high school yearbook it says that my goal is to become a jazz pianist like Oscar Peterson.”

Career as Educator

Peterson operated the Advanced School of Contemporary Music in Toronto from 1960 to 1962 with Phil Nimmons, Ray Brown and Ed Thigpen. The school was closed after only three years due to the demands of Peterson’s performance schedule. But it drew jazz students from cities throughout North America. The faculty grew to include Erich Traugott (trumpet), Jiro “Butch” Watanabe (trombone) and Ed Bickert (guitar). Peterson’s own pupils included Skip Beckwith, Carol Britto, Brian Browne, Wray Downes and Bill King.

Peterson also wrote four volumes of his Jazz Exercises and Pieces for the Young Jazz Pianist, which were published in the mid-1960s. He was also present at the inception of the Banff Centre for the Arts Jazz Workshop in 1974. He returned to an academic setting in 1985 as adjunct professor of music at York University. He also served as chancellor there from 1991 to 1994 and became an honorary governor in 1995. He also assisted in establishing the Oscar Peterson Jazz Research Centre at Winters College, York University’s school of fine arts.

Radio and TV Broadcasts

After his early career on CBC Radio, Peterson was not heard with any regularity on the network, save for his recordings. That changed in the 1970s, when Jazz Radio-Canada broadcast concert performances, and That Midnight Jazz and The Entertainers offered profiles. Peterson himself was host for the short series Oscar Peterson’s Jazz Soloists (1984) and Jazz at the Philharmonic (1990).

He was seen in several specials on CBC TV, including: Oscar Peterson Inside (1967); A Very Special Oscar Peterson (1976); Oscar Peterson’s Canadiana Suite (1979), a performance with a 37-piece orchestra of his Canadiana Suite with corresponding scenic footage; and the 13-episode series, Oscar Peterson and Friends (1980). He was also host in the mid-1970s of CTV’s Oscar Peterson Presents (1974), and BBC TV’s Piano Party (1976) and Oscar Peterson Invites… (1977). CBC Radio presented a seven-part documentary on him in 1994. The CBC TV biography series Life and Times featured him in the 2003 episode “Oscar Peterson: Keeping the Groove Alive.”

Canadian Sidemen

Although most of Oscar Peterson’s groups were US-based, he periodically employed Canadians as his sidemen. Among them were bassists Michel Donato, Steve Wallace and David Young; drummers Terry Clarke, Jerry Fuller, Stan Perry and Ron Rully; and guitarist Lorne Lofsky.

Personal Life

Peterson was married four times, first to Lillian Fraser (1944–58), with whom he had two sons and three daughters. After his marriage to Sandra King (1966–76), he had one daughter with his third wife, Charlotte Huber (1977–87). His marriage to Kelly Peterson (née Green), with whom he had one daughter, lasted from 1990 until his death in 2007.

Honours

Peterson received a multitude of honours and awards, from international recognition of the highest order to schools and scholarships named in his honour. During the 1976 Olympic Summer Games in Montreal, he was awarded a key to the city. In 1978, he was inducted into the Canadian Music Hall of Fame. In 1990, the Festival international de jazz de Montréal established the annual Oscar Peterson Award to recognize “a performer’s musicianship and exceptional contribution to the development of Canadian jazz.” In 1993, he was awarded the Glenn Gould Prize. That award’s namesake is considered Peterson’s only rival among Canadian pianists.

Concordia University named a concert hall in Peterson’s honour in 1998; it also created the Dr. Oscar Peterson Jazz Scholarship with Verve Music Group Canada in 2000. In 1999, Peterson became the first Canadian and the first jazz musician to receive the Praemium Imperiale Award, the arts equivalent of the Nobel Prize, from the Japan Art Association.

In 1991, Peterson began to deposit his papers at the National Library of Canada (now Library and Archives Canada). It curated a major exhibition about him titled Oscar Peterson: A Jazz Sensation. It opened on Canada Day 2000 and ran until September 2001.

In 2000, Peterson received the UNESCO International Music Prize and a citation from US President Bill Clinton recognizing his achievements. Also that year, his album, The Trio, was designated a Masterwork by the Government of Canada’s AV Preservation Trust. In 2001, the cities of San Jose, Oakland and San Francisco, California, declared the week of 28 August to 2 September “Oscar Peterson Week.” The US House of Representatives presented him with a commendation in recognition of his contributions to society.

In 2002, Peterson became the first person inducted into the Canadian Jazz and Blues Hall of Fame. He also received a lifetime achievement award that year from the Urban Music Association of Canada. In 2003, Mississauga named a street Oscar Peterson Boulevard, and the government of Austria issued a stamp in his honour. In 2005, a public school in Mississauga was named after him, and Canada Post made him the first living person other than a reigning monarch to appear on a stamp. In 2008, “Hymn to Freedom” was inducted into the Canadian Songwriters Hall of Fame.

In 2010, York University’s Department of Music created the $40,000 Oscar Peterson Entrance Scholarship. In 2013, Peterson was posthumously inducted into Canada’s Walk of Fame. A life-sized sculpture of Peterson, unveiled on 30 Jun 2010 by Queen Elizabeth II and the Duke of Edinburgh, sits permanently outside the National Arts Centre in Ottawa.