His Sheet Music is available in our Library

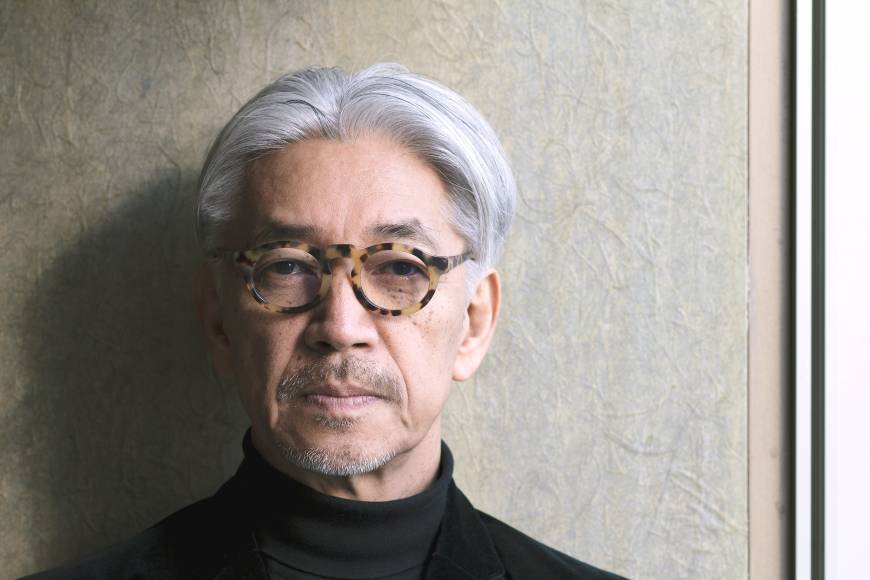

Ryuichi Sakamoto offers his thoughts on politics, Japan and how his music will change ‘post-cancer’.

Ryuichi Sakamoto interview

“The Professor” is back in town. Last weekend, Ryuichi Sakamoto took the stage at Tokyo Opera City for the debut concert of the Tohoku Youth Orchestra, a 105-strong ensemble of young musicians from Iwate, Miyagi and Fukushima prefectures, which counts him as its musical director.

Though he isn’t inclined to make a fuss about these things, the occasion also had personal significance for the 64-year-old composer and musician, a longtime New York resident. It was the first concert Sakamoto had played since undergoing treatment for throat cancer in 2014, canceling all engagements in what must be one of the music industry’s busiest work schedules. As he later remarked, it was the first extensive time off he’d had for 40 years.

“It’s the closest I’ve come to death during my lifetime,” he tells The Japan Times, speaking the day after the Tohoku Youth Orchestra concert. “I feel differently since I came back from that place, compared to before. I want to capture the mood I have now, post-cancer, in my music.”

Sakamoto’s unobtrusive return to the limelight was heralded by the soundtracks that he composed for Yoji Yamada’s “Nagasaki: Memories of My Son” and, in collaboration with Carsten Nicolai (aka Alva Noto), for Alejandro G. Inarritu’s “The Revenant.” (The latter film, which earned him a Golden Globe nomination, opens in Japan on April 22.)

Now there’s also the prospect of a new album of original material, his first since 2009’s “Out of Noise.”

“I have a lot of sketches and ideas, but when you don’t use them they get stale,” he says. “You’re changing every day, right? Your curiosities and ambitions change, your ear changes, the music you like changes — and the music you want to make, too … I’m planning to begin work on an album when I get back to New York, but I think I’m probably going to start from scratch.”

Prior to that, Tokyo audiences can catch Sakamoto again next weekend, when he presides over a three-day festival at Yebisu Garden Place, to mark the 10th anniversary of his Commmons label. Rather than perform a headlining set himself, he’ll be playing support roles throughout the weekend: sitting in with some of the musicians, hosting discussions and providing piano accompaniment for communal rajio taisō (radio calisthenics) sessions with the crowd.

Sakamoto established Commmons in 2006 with the rather lofty goal of creating “a place where new relationships can be built between the music industry, the audience, artists and creators.” In addition to releasing music by artists such as Boredoms, Sotaisei Riron and Kotringo, the label has provided a platform for its founder’s prolific musical output, as well as a series of scholarly journals.

One of Sakamoto’s current areas of inquiry is traditional Japanese music, once a blind spot in his otherwise rich musical vocabulary. He studied composition and ethnomusicology at Tokyo University of the Arts, leading his Yellow Magic Orchestra bandmate Yukihiro Takahashi to nickname him “Professor” — a moniker that stuck. Yet the musical system employed by noh theater remains something of a mystery.

“I could understand Bach, but not noh,” he says with a laugh. “It has a 600-year history — it’s very deep.”

Sakamoto has been based in New York since 1990, and seems to value the perspective that life as an expatriate has given him on his native country; his increasing appreciation of Japanese performing arts such as noh, kabuki and gagaku is one example.

“When I lived in Japan, I only noticed the bad aspects of the country,” he says. “I didn’t really like Japan then, but when I moved overseas I was able to appreciate the good side more. The quality of the craftsmanship, the temples and Japanese gardens. … As I’ve got older, I’ve started to appreciate the precious parts of Japanese culture that you don’t find in other countries.”

When he first relocated to the States, Sakamoto was that rarest of things: a Japanese celebrity with global clout. Both in his solo work and with YMO, the techno-pop trio he formed with Takahashi and Haruomi Hosono in 1978, he had positioned himself at the vanguard of synthesizer- and sample-based music.

But it was his movie soundtracks that clinched his international renown, including for Nagisa Oshima’s “Merry Christmas, Mr. Lawrence” (in which he co-starred opposite the late David Bowie) and Bernardo Bertolucci’s “The Last Emperor,” which won him an Academy Award in 1988.

Sakamoto’s subsequent career may not have yielded such boundary-breaking music, but in other ways it has been awfully prescient. He began to use environmentally friendly packaging for his albums in the early 1990s, and was powering his tours on renewable energy long before Radiohead took up the idea. He was also an early adopter of Internet technology, staging his first live online broadcast of a concert in 1995.

“Internet speeds were still really slow then,” he recalls with a laugh. “We’d call it a concert, but you were basically watching static images that changed once every 10 seconds. The audio was all choppy, too.”

While Japanese labels were enjoying record-breaking CD sales during the late ’90s, Sakamoto had already anticipated how online distribution would upend the music industry. He lobbied for changes in the way that copyright licensing body JASRAC (Japanese Society for Rights of Authors, Composers and Publishers) handled music rights online, and cautioned the retail behemoths that their boom times were about to end.

“I was telling the Tower Records people in 1996 or 1997: ‘(CD shops) are going to disappear, you need to think about it,’ ” he says. “I thought they’d be able to get in early and make something like what we have with the iTunes Store now, but they couldn’t seem to do it.”

After spending his career championing technological innovation, Sakamoto is a little rueful about where things have ended up. In a world of YouTube, Spotify and Apple Music, few young people would think to pay to listen to music. Life isn’t much easier for session musicians: Why hire a band for a TV or film soundtrack when you can use sophisticated software synthesizers instead?

“There are still young people hoping to become professional musicians, but it’s so tough now, they’d be better off giving up,” he says. “I’d tell them to get a different job and play music as a hobby.”

“Everybody’s hurting now, whatever the genre,” he continues. “The only people making money are DJs.”

Sakamoto has a talent for statements like this. Famously outspoken, in recent years he’s lent his voice to campaigns on issues including the relocation of the U.S. Futenma air base in Okinawa, government restrictions on free speech, and the police crackdown on all-night dance clubs.

But he’s most closely associated with environmental causes, notably his advocacy of renewable energy and staunch opposition to nuclear power. Following the triple meltdown at the Fukushima No. 1 nuclear plant in March 2011, Sakamoto quickly emerged as an influential figurehead in the anti-nuclear movement. In 2012, he organized the No Nukes festival at Makuhari Messe in Chiba, inviting Kraftwerk and a roster of well-known Japanese artists.

As a veteran of Japan’s late-1960s student protest movement, which he joined when he was still a high-school student, he was comfortable amid the demonstrations that galvanized the country during 2011 and 2012.

“With the demos we held in the ’60s, everyone was wearing helmets and masks, holding poles and fighting with riot police — it was totally different,” he says. “I think the way we do it now is better. Anyone can take part.”

He expresses regret about the political retrenchment that has occurred since the election of Shinzo Abe’s LDP administration in December 2012: “For a couple of years there, I hoped that genuine democracy might take root in Japan … I felt there were more people who were openly speaking their minds, without being influenced by others.”

Does he worry a lot about Japan’s future?

“I do, I do. One of the unfortunate things that’s happened in the three or so years since Abe came to power is that Japanese people are going on about how brilliant Japan is: ‘This is great! This place is amazing!’ There are too many TV programs and campaigns like that, and I’m getting a little sick of it. It’s fine if people from outside the country praise you like that, but to say it yourself — things like ‘Cool Japan’ — I don’t think that’s ‘cool.’ ”

Being one of the country’s most internationally renowned cultural icons, Sakamoto may seem like an obvious ambassador for the government’s campaign to promote Japanese soft power overseas. So it’s surprising when he says that he hasn’t even been approached by the apparatchiks behind Cool Japan.

Maybe it’s because the campaign originates within the halls of the Ministry of Economy, Trade and Industry — the main cheerleader for Japan’s nuclear power industry.

“I hate them, and I think the feeling’s mutual,” he says.

The organizers of the 2020 Tokyo Olympics can also strike Sakamoto’s name from their invitation list. Although he composed and conducted the music for the opening ceremony at the Barcelona Games in 1992, he says that he wouldn’t be interested in taking part when the event returns to Japan.

Asked why, he reels off a list of the problems that continue to afflict the Tohoku region: the tens of thousands of people still living in temporary housing, the nuclear disaster evacuees unable to return home, the ongoing problems with cleanup efforts at the Fukushima No. 1 nuclear plant.

“It’s not ‘under control’ at all, is it?” he says, echoing the words used by Abe in his speech to the International Olympic Committee in 2013. “They should be making that their first priority.”

For Sakamoto, the way to end Japan’s current malaise is through encouraging fresh thinking — though he concedes that this is difficult in “a society where it’s hard to say things that others don’t agree with.”

“You won’t get original thinking in an environment like that. The ideas won’t come, and the talented people will just end up going overseas,” he says as we wrap things up.

“I’ve been saying this for a long time,” he concludes, “but if you take Sony, which is a company that really represents Japan, and compare it to Akira Kurosawa — just one person — Kurosawa is probably worth more worldwide. A lot of people don’t seem to get that.”

Rock/Pop/Contemporary Music/New Age Sheet Music

坂本 龍一 Ryuichi Sakamoto Full Album 2020 – 坂本 龍一 Ryuichi Sakamoto Best Of

Track List:

0:00 Energy Flow 4:08 The Last Emperor 8:38 Rain 12:00 Merry Christmas Mr Lawrence 16:05 The Last Emperor OST 22:04 The Sheltering Sky 28:05 Forbidden Colors 32:56 A Flower Is Not A Flower 39:38 Undercooled 43:14 Solitude 48:11 BABEL 53:26 Blu 58:42 Amore 1:03:52 Wuthering Heights 1:10:16 Opus 1:15:10 Rain 1:18:22 Moon 1:22:03 Anna