Browse in the Library:

Beethoven – Piano Sonata No 17 in D minor op 31 2 “Tempest” performed and commented by Glenn Gould

Piano Sonata No. 17 (Beethoven)

The Piano Sonata No. 17 in D minor, Op. 31, No. 2, was composed in 1801–02 by Ludwig van Beethoven. It is usually referred to as The Tempest (or Der Sturm in his native German), but the sonata was not given this title by Beethoven, or indeed referred to as such during his lifetime.

The name comes from a reference to a personal conversation with Beethoven by his associate Anton Schindler in which Schindler reports that Beethoven suggested, in passing response to his question about interpreting it and Op. 57, the Appassionata sonata, that he should read Shakespeare‘s Tempest; some however have suggested that Beethoven may have been referring to the works of C. C. Sturm, the preacher and author best known for his Reflections on the Works of God in Nature, a copy of which he owned and, indeed, had heavily annotated.

Although much of Schindler’s information is distrusted by classical music scholars, this is a first-hand account unlike any other that any scholar reports. The British music scholar Donald Francis Tovey says in A Companion to Beethoven’s Pianoforte Sonatas:

With all the tragic power of its first movement the D minor Sonata is, like Prospero, almost as far beyond tragedy as it is beyond mere foul weather. It will do you no harm to think of Miranda at bars 31–38 of the slow movement… but people who want to identify Ariel and Caliban and the castaways, good and villainous, may as well confine their attention to the exploits of Scarlet Pimpernel when the Eroica or the C minor Symphony is being played (pg. 121).

Innovations in Beethoven’s Op. 31 No. 2 “Tempest” Sonata

The Op. 31 No. 1 & No. 2 sonatas were most likely written in Heilegenstadt, as is suggested both by their presence in the Kessler sketchbook (dating them to 1801-1802) and Ferdinand Ries’s accounts. According to Czerny, after writing his Op. 28 sonatas, Beethoven said to his friend Krumpholtz: “I am not very well satisfied with the work I have thus far done. From this day on I shall take a new way”, which Czerny later associated with the Op. 31 sonatas. Beethoven’s comment about the “new way” has created a lot of controversy, and different scholars have had different interpretation of what it meant.

Nonetheless, the sonata Op. 31 No. 2 is unquestionably one of the greatest classical sonatas and occupies an important place within Beethoven’s career. Rosen calls the opening of the Op. 31 No. 2 sonata “the most dramatic that Beethoven had yet conceived, with a contrast of tempos and motifs, and a radical opposition of mood.” The Op. 13 sonata “Pathétique” also starts off with a similar juxtaposition of tempos and motifs, but in that case, the materials present in the starting Grave/Allegro molto con brio do not germinate the rest of the movement as will be shown to be the case in Op. 31, no. 2.“The opening motif…is a motto and it will govern the entire work”.

This opening is constructed in a set of antecedent/consequent phrases. The first phrase, in Largo and pianissimo, is an upward arpeggiation of an A major chord in first inversion that starts out as a rolled chord. Nonetheless the top note of the rolled chord – A – continues melodically into a rhythmicized horizontalization of the A chord. The consequent to this is a dynamic Allegro phrase characterized by falling two-note slurs in the right hand that are contrasted by a rising bass line.

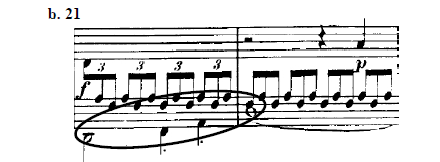

This material repeats bar 7, now transposed into F major, but there is no clear cadence to be found until bar 21, where, in a seemingly new thematic material, the last four notes of the Largo antecedent phrase are now taken up in the bass register while the right hand accompanies by tempestive fast triplets in forte.

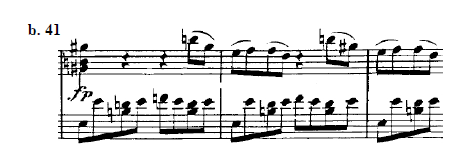

An important aspect to keep in mind here is the registral space that is opened up between the iterations of the main thematic material in the bass and the melodic responses in the right-hand line. At bar 41, the two-note slur motivic figure of the consequent phrase from bars 2-5 returns, but in a different melodic and harmonic guise.

Thus, the first two pages of the sonata generate from the first five bars, as the closing theme of the exposition (bars 75-87) derives its melodic content from the 5-4-3-2- 1 descent of the initial Allegro motive, though now in the dominant key. As Jones notes, even the chromatic turn around of bars 5-6 returns in new guises but with the same melodic pitches in bars 22 and 55.

Thus the first two pages of the sonata generate from the first five bars, as the closing theme of the exposition (bars 75-87) derives its melodic content from the 5-4-3-2-1 descent of the initial Allegro motive, though now in the dominant key. As Jones notes5, even the chromatic turn around of bars 5-6 returns in new guises but with the same melodic pitches in bars 22 and 55.

The development starts with a re-interpretation of the Largo rolled chords as arpeggios, which are longer (i.e. containing more notes) and thus allow for higher expressivity. After three permutations of the Largo motive, very unexpectedly the material of bars 21-40 (based on the Allegro part of the main theme) returns now in F# minor and fortissimo, thus completely skipping the actual Allegro theme, as it appears on bars 2-5.

Even the earlier (and sometimes not most convincing) analyses of the piece have noted the unusual nature of this development section, which is not constructed, as most developments in classical sonatas were, upon sequences and breakdown of motives, but rather it moves to a hole new key area. The idea of keeping the exposition materials practically intact (though transposed to a foreign key) is thus definitely a new element that Beethoven brings with this sonata.

Nonetheless, what does happen as expected in this development section is an increase in tension, which is in part achieved through a gradual and carefully paced ascent in the bass line, from F# to D. Rosen notes that “the use of a rising bass at moments when the tension must be heightened is indispensable to Beethoven starting with op. 2, no. 2”.

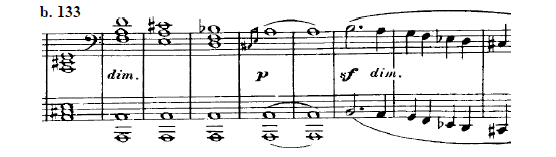

In the first movement of Op. 31, no. 2, the bass rises gradually over 20 bars (98-118) as the development section gets underway. An implied augmented sixth chord based on Bb propels the piece into a 12-bar prolongation of the A major dominant in fortissimo (bars 121- 132). Then a 5 – 4 – 3 – 2 – 1 melodic descent (for A major) in whole notes, with an A pedal in the bass, brings us to bar 137, where we get a hint of the recapitulation, through the C# and E grace notes that create an A chord.

The sforzando B flat in bar 139 then implies a dominant ninth chord, which is never played out vertically but is rather filled in horizontally as the 9th interval is outlined on the strong beats of bars 139 through 143 . It is interesting to note here that the dominant ninth plays an extremely important role in Beethoven’s compositions in preceding the recapitulation (as will also be shown even more prominently in the second and third movements) and it plays that same role here of creating a tension and an expectation of future release.

Nonetheless, it should be remembered that the main “theme” in the exposition did not include a single root position tonic chord, and thus the recapitulation at bar 143 reinstates not the stability of the tonic but rather the instability of the dominant, as present in the exposition.

Yet, we are now in a very different place than we were in the beginning, and the Largo is a much longer and more convoluted version of the first two bars. This is possibly the most extraordinary moment of the entire sonata, where the “expressive implications [of the mysterious arpeggios] are made explicit”. Within the recitative passage, the dominant ninth chord is again horizontally implied as the tension is not released but rather increased in a moment where, though in pianissimo, uncertainty of expectations is heightened to the edge.

With the second iteration of the Largo motive (starting with the original first inversion C major chord) the piece comes to a halt at the tonally ambiguous Ab of bar 158. Beethoven swiftly enharmonizes the Ab to a G# that is part of a first inversion C# major chord leading to improvisatory arpeggios in F# minor. What is lacking in this recapitulation section is the strong tonal arrival on D minor that came originally at bar 21. In fact the whole passage of bars 21-40 is not recapitulated.

The material that was originally in the dominant (starting at bar 41), as expected, is now recapitulated in the tonic, but it should not go unnoticed that the only strong cadence and arrival in the tonic (after that of bar 21) comes at the end of the movement (bar 217).

This concept is very important not only for the development of Beethoven’s personal style and that of classical music, but also in its role in the birth of romanticism. It is noteworthy that already in 1802, with Op. 31 No. 2 Beethoven creates a “sense of an unstoppable transformation process by constructing the music in unprecedentedly long spans, avoiding strong cadential closure”.

This sense of unstoppable transformation in the first movement is also due the “processual” character of its structure. I have thus far described the different musical phrases as being in the exposition, development, or recapitulation, thus conforming to the generally accepted notion of sonata form. Nonetheless one of the things that make Op. 31 No. 2 special is its redefinition of sonata form in terms of a transformational process, rather than a neatly divisible form.

It has already been mentioned the motivic relationsbetween the different materials in this movement, but it is also important to note howthese materials function structurally. At the outset of the piece, the rolled/arpeggiated A major chord in the first two bars appears to be more like introductory material that precedes the main theme than the exposition of the main theme itself.

It is only later in the piece, when this material returns, both reworked (as in bar 21) and verbatim (as in bar 143) that its significance is realized. In Dahlhaus’ words: “bar 1 first presents itself as a prelude lacking in thematic significance, later (when viewed in retrospect from bar 21) as the anticipation of the theme and finally (after it has emerged that bars 21-40 are a modulating developmental passage) as the actual exposition”. “Bars 1-2 ‘are’ not either prelude, or anticipation or thematic exposition” but they set in motion a “dialectic process, where earlier meanings continue to coexist on equal footing with later ones”.

The listener thus “follows the process of transformation” in which the motives/themes fulfill several functions at a time and the processual aspect of structure coexists with, if not supersedes the theoretical divisions of sonata form. In this case, in fact, the fact that bar 1 cannot easily be identified as either introduction or exposition is in no way a weakness. Rather, “ambiguity should be understood as an aesthetic quality” as it is “the very contradictions of the form that constitute its artistic character”. While the motivic relationships and their transformations are probably the clearest within the first movement, there are notable connections between the movements as well.

The second movement “transforms elements from the first movement in a warmer context”. The arpeggio from bar one of the first movement is now re-taken in the warmer and more stable Bb key (in root position), while the “double dotted rhythms are reminiscent of the recitative”.

continue to coexist on equal footing with later ones”12. The listener thus “follows the process of transformation” in which the motives/themes fulfill several functions at a time and the processual aspect of structure coexists with, if not supersedes, the theoretical divisions of sonata form. In this case, in fact, the fact that bar 1 cannot easily be identified as either introduction or exposition is in no way a weakness.

Rather, “ambiguity should be understood as an aesthetic quality” as it is “the very contradictions of the form that constitute its artistic character”. While the motivic relationships and their transformations are probably the clearest within the first movement, there are notable connections between the movements as well.

The second movement “transforms elements from the first movement in a warmer context”. The arpeggio from bar one of the first movement is now re-taken in the warmer and more stable Bb key (in root position), while the “double dotted rhythms are reminiscent of the recitative”. It is quite striking to note that the last two notes (F – D) outlined in the melody of the final chords of the first movement are also the same exact notes that are outlined in the first melodic passage of the second movement (bar 2), though now in the new harmonic context.

As Taub notes, it is quite important as a pianist to voice the last two chords of the first movement to the top, in such a way that they will remain in the listener’s auditory memory until they are picked up again in the second movement.

In contrast to the first movement’s design, the structure of the second movement is much simpler and more easily and unequivocally identifiable as a sonata form withoutdevelopment. On the other hand, there are several subtle compositional links with the first movement. One of the key characteristics of this movement is the registral space that is opened at the very beginning, which is reminiscent of the technique used in the first movement (bars 21-40 and 99-121).

Similarly to the first movement, “the opening thematic statement is richer in what it implies, than in what it actually contains”. As the first theme material repeats at bar 9, what was essentially hollow space in the first eight bars starts to get filled in, as the rhythmic pace also picks up.

The transition passage, with its relentless and tension-building character provided by the drum-roll figure in the bass leads into the second theme (at bar 31, in the dominant, F major), which is by contrast the most serenely beautiful material of the entire sonata. Nonetheless, after only eight bars, the tension starts building, as Beethoven introduces again the dominant ninth chord that had such a prominent role in the opening movement to prepare for the return of the tonic in the recapitulation.

The second time through the first theme (bars 51-59) Beethoven completely fills in the initial registral gap with cascading and notes that embellish the main melodic line. After the recapitulation in the tonic of the second theme and a quick motion to the subdominant (bar 85), the main theme returns for a final time at the coda (bar 89), where the registral gap again widens, and the texture gets thinner.

The last bar is a very concise distillation of the motivic material that as made up most of the movement, and at the same time it foreshadows the melodic motion (3 – 2 – 1) that the main theme of the third movement is made of.

The second movement, both because it is cast in the most traditional form of the three movements, and because of its relatively symmetric form serves as a central axis for the outer two movements, which share several characteristics, especially in terms of their harmonic language.

While, in contrast to the first movement, the third movement starts with a clear tonic D in the bass, the pedal A in the tenor voice does introduce a tonal ambiguity that, as in the first movement, is really only resolved at the end. While from the very beginning the 3/8 Allegretto sets up perpetum mobile-type rhythmic activity, it is only at bar 30 that the true “Sturm und Drang” nature of the first theme appears.

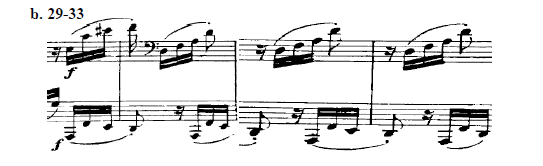

Here, now in forte (while the first eight bars were in piano) the melodic content of the first theme is transferred to the low register of the bass while the right hand imitates the left hand rhythm but off by two eighth notes, thus creating an incredible pull and tension in the rhythmic structure.

appears. Here, now in forte (while the first eight bars were in piano) the melodic content of the first theme is transferred to the low register of the bass while the right hand imitates the left-hand rhythm but off by two eighth notes, thus creating an incredible pull and tension in the rhythmic structure.

After this figure repeats transposed down to C major, through an augmented sixth chord on F we arrive at the second theme (bar 43), which is yet another reconfiguration, in a different metric and harmonic context, of the two note slur figure from the first movement theme.

We have now clearly modulated to the dominant A minor, butas in the first movement, Beethoven avoids a strong cadential closure (here in the dominant) through “elision” (bar 51) and “interruption” (bars 59 and 63). Even when A minor is reached through a perfect cadence (bars 67 and 73), the subito piano transforms the phrase endings into the start of a new forward-propelling phrases. Anotherdominant ninth chord at the last four bars of the exposition lead (after the repeat) to an unexpected F# diminished chord that starts the development section.

As Jones notes, this development section is very characteristic in its persistence of the same rhythmic pattern, derived from the first theme – in fact the second theme material appears nowhere in the development. The first theme material does appear almost verbatim and the choice of the key to which Beethoven transposes it here (bar 150) – B flat minor– is quite intriguing. After a long transitional section including, at its end (bars 189-214), a 26-bar longprolongation of the dominant ninth sonority (whose importance in preceding the recapitulation has been noted in the previous movements), the opening theme returns again in the tonic.

As expected of a recapitulation the second theme is nowrestated in the tonic. Nonetheless, the original “Sturm und Drang” material from bar 29 is nowtransposed to the key of B-flat minor.As noted earlier, in the first movement, Beethoven first uses F# minor in the beginning of the development section (bar 98) and then returns to this foreign key in the middle of the recapitulation (bar 161), where improvisatory material replaces the theme of bars 21-40, which is not recapitulated. Of course, the theme of bars 21-40 preceded the recapitulation, but it was there constructed in F# minor, the key that returns at bar 161.

A similar maneuver happens in the third movement, whereBeethoven uses in repetition the key of Bb minor. Starting in bars 130 of the development section, the key of Bb minoris emphasized until finally, at bar 150, the first theme suddenly reappears (bars 150½- 157½ are a direct transposition to Bb minor of the first theme). As in the first movement, in the third-movement recapitulation section, Beethoven breaks out of the normal sequence of keys to go back to Bb minor (the “foreign” key, as F# minor was in the first movement).

As Rosen remarks (p. 172), Beethoven again uses this idea of returning, in the recapitulation, to the most unusual key of the development section in his “Hammerklavier” Sonata, but Op. 31 No. 2 is his first attempt at such a technique and thus represents a very important innovation.

It is important to note here Beethoven’s merits with regards to establishing key-relationships as an important compositional element. Toveyobserves that “the darker colors, such as Ab to C (Vi to I) are often evident in Mozart” while “the brighter key relations, such as C to E (I to III) are apparent in Haydn’s late works”. But “neither Haydn nor Mozart took the risk of giving a remote key an essential function in a continuous and highly organized movement”.

It is only after Beethoven, especially with Schubert that we see the major third key relation becoming typical. For example, in the exposition of the String Quartet in G Schubert goes through a tonal sequence D-F#-Bb-D. Curiously, these are the same keys that Beethoven goes through in his Op. 31 No. 2 sonata, but in the sonata they are all in their minor mode.

Nonetheless, it must be noted that Beethoven was experimenting with key areas for some time and the innovations did not start with Op. 31 No.2, rather they continued in the path of Beethoven’s search for an individual style.

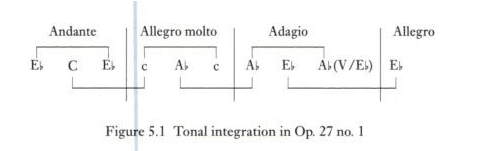

In the sonata Op. 26 (written 1800-1801) Beethoven tries the idea of remaining in the same key of Ab throughout the four movements (the third movement being in the minor mode). Op. 27 No. 1 (written 1800-1801), on the other hand, goes from Eb (movement 1 – Andante) to C minor (movement 2 – Allegro molto e vivace) to Ab (movement 3 – Adagio con espressione) and back to Eb (movement 4 – Allegro vivace).

The sonata Op. 27, no. 1 is one of the set of two sonatas subtitled by Beethoven “Quasi una fantasia”, the second of which is the slightly more celebrated “Moonlight” sonata. In both these sonatas, Beethoven tries out new models for the different component movements, defying the general expectations of what a piano sonata was supposed to be.

While the “Moonlight” with its contemplative first movement possibly gave way to more speculation, Op. 27 No. 1 is definitely worthy of attention. Two elements particularly in this sonata are an important precursor to Op. 31 No. 2. Firstly, the key relations (especially in major thirds) are present not only between the movements, but also within the movements. Jones shows very clearly the big-scale tonal scheme of the sonata:

Secondly, in an unprocessed way, we find here an attempt to integrate the movements within a unified work by means of using the same motive in two different movements. The first 6 bars of the third movement are largely cut and pasted before the coda in the fourth movement, transposed by a fifth up. Obviously this relationship is not extremely subtle, but it can be seen how Beethoven then reuses this idea of motivic unity in Op. 31 No. 2 in a less apparent but exceptionally consistent manner.

In the sonatas Op. 27, no. 2 and Op. 28 Beethoven goes back to the idea of one-key for the entire work, with C# minor (Adagio sostenuto) – Db (Allegretto) – C# minor(Presto agitato) in Op. 27 No. 2 and D (Allegro) – D minor (Andante) – D (Scherzo) – D (Rondo)in Op. 28. Then he returns, with Op. 31, no. 1, to the 3-movement sonata with G-C-G the keys of the respective movements, but he uses the “foreign”, major third-related key of B major for the second subject at the first movement’s exposition (bar 66), after the first subject’s G major. “The Op.20’s sonatas confirm that for Beethoven the piano sonatas were a field of experimentation”.

Especially with the “quasi una fantasia” sonatas Beethoven attempts to unite the different movements as one continuous composition and, after having toyed with the number, quality and inter-relation of the movements, Beethoven concentrates his experimentation in Op. 31, no. 2 on the inner workings of each movement. In a way, within the general goal of creating a unified sonata, his focus shifts from the outer appearance of the movements (in the Op. 20’s) to the inner workings of each movement (Op. 31).

A final note about Beethoven’s experimentations in the Op. 31 sonata has to do not with structure, but with sound. It is fascinating that the three movements of the Sonata Op. 31, no. 2, as well as Op. 31, no. 1, end quietly, without the classical formal ending with big chords31. Considering the fact that both these sonatas were written during Beethoven’s permanence in Heilegenstadt, it would not be a very far-fetched theory to say that this experimentation with sound might have been at least in part due to Beethoven’s increasing awareness of his hearing loss32.

Nonetheless, the soft ending of each movement also serves to “prolong the atmosphere beyond the final chords”. This not only imbues a greater meaning to the short moments of silence between the movements but it also aids in creating the feeling of the sonata as a continuous work, to which end also serve, the motivic relationships within and between movements as well as the avoidance of cadences.

Thus, whether autobiographically induced or not, the experimentation with sound eventually has an effect in the structural unity of the piece. Many scholars have considered Beethoven’s realization of his future permanent hearing loss in Heilegenstadt during 1802 as a crucial point that defined his compositional style. Solomon claims that Beethoven’s this served as a “fresh start”, a turning point in his style.

Nonetheless, such absolutist claims should be read with caution. Kinderman points to letters of Beethoven to Wegeler and Amenda in 1801 where it is clear that already for at least a couple of years before that he has been seriously preoccupied with his hearing loss. Thus it is very hard to identify within a moment or even a few weeks/months Beethoven’s personal crisis associated with his hearing loss. In Jones’ words, “rather than representing a turning point [the Heilegenstadt testament] may be seen as continuing a crystallization of thoughts that Beethoven had been exploring for some time”.

On the musical side, it has also been shown here that, while the Op. 31, no. 2 sonata presents multiple innovative compositional techniques, many of such techniques were already used or toyed with in previous works. Further, to say that Beethoven’s “new way” started suddenly in this one piece would be a very simplistic and even offensive way to regard music of such stature. Perhaps closer to the truth is the notion that in his long artistic life of improvement and innovation, Op. 31, no.2 is but oneof many noteworthy examples.

Bibliography

(Tovey 1931; Tovey 1944; Thayer 1964; Sonneck 1967; Tyson 1973; Webster 1978; Kerman 1983; Broyles 1987; Solomon 1988; Wolff 1990; Dahlhaus 1991;Kinderman 1995; Lockwood 1996; Jones 1999; Rosen 2002; Taub 2002; Lockwood2003)Broyles, M. (1987). The Emergence and Evolution of Beethoven’s Heroic Style. New York, NY, Excelsior Music Publishing Co.Dahlhaus, C. (1991). Ludwig van Beethoven: Approaches to his Music. Oxford, UK, Oxford University Press.Jones, T. (1999).

Beethoven: The ‘Moonlight’ and other Sonatas Op. 27 and Op. 31. Cambridge, UK, Cambridge University Press.Kerman, J. T., Alan (1983). The New Grove Beethoven. New York, NY, W. W. Norton & Company.Kinderman, W. (1995). Beethoven. Berkeley and Los Angeles, CA, University of California Press.Lockwood, L. (1996). “Reshaping the Genre: Beethoven’s Piano Sonatas from Op. 22 to Op. 28 (1799-1801).” Israel Studies in Musicology 6: 1-16.Lockwood, L. (2003). Beethoven: the Music and the Life. New York, NY, W. W. Norton & Company.Rosen, C. (2002). Beethoven’s Piano Sonatas: A Short Companion. New Haven, CT, Yale University Press.Gjergji GaqiMU 48317Solomon, M. (1988).

Beethoven Essays. Cambridge, Mass., Harvard University Press.Sonneck, O. J. (1967). Beethoven: Impressions by his Contemporaries. New York, NY, Dover Publications Taub, R. (2002). Playing the Beethoven Sonatas. Portland, OR, Amadeus Press.Thayer, A. W. (1964). Life of Beethoven. Princeton, NJ, Princeton University Press.Tovey, D. F. (1931). A Companion to Beethoven’s Piano Sonatas. London, UK, The Associated Board of the R.A.M. and the R.C.M.Tovey, D. F. (1944). Beethoven. London, UK, Oxford University Press.Tyson, A. (1973).

Beethoven Studies. New York, NY, W. W. Norton & Company.Webster, J. (1978). “Schubert’s Sonata Form and Brahm’s First Maturity.” 19th Century Music 2(1): 18-35.Wolff, K. (1990). Masters of the Keyboard: Individual Style Elements in the PIano Music of Bach, Haydn, Mozart, Beethoven, Schubert, Chopin, and Brahms. Bloomington, IN, Indiana University Press.