- A musical Analysis of the Compositions of Bill Evans, Billy Strayhorn and Bill Murray

- Sheet Music download available in our (YOUR) Library.

- Bill Evans’s Background

- Influences on Bill Evans.

- Approach to Composition.

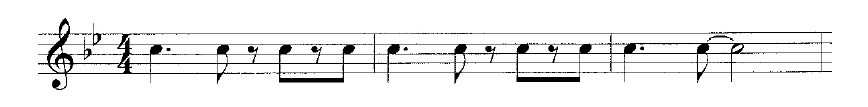

- Bill Evans – Waltz For Debby

- Billy Strayhorn’s Background

- Influence on Billy Strayhorn:

- Billy Strayhorn and the Duke Ellington Orchestra:

- DUKE ELLINGTON “Daydream” BILLY STRAYHORN (1968)

- Bill Evans Compositional Style

- Key Signatures for Bill Evans Compositions

- Billy Strayhorn’s Compositional Style

- The Music of Bill Murray

- Appendix I: Bill Evans, Billy Strayhorn, Bill Murray Compositions Analyzed for Musical Elements

- Appendix 2: Summary of Composition Analysis for Selected Bill Evans, Billy Strayhorn and Bill Murray Compositions

- Bill Evans Composition Summary Analysis

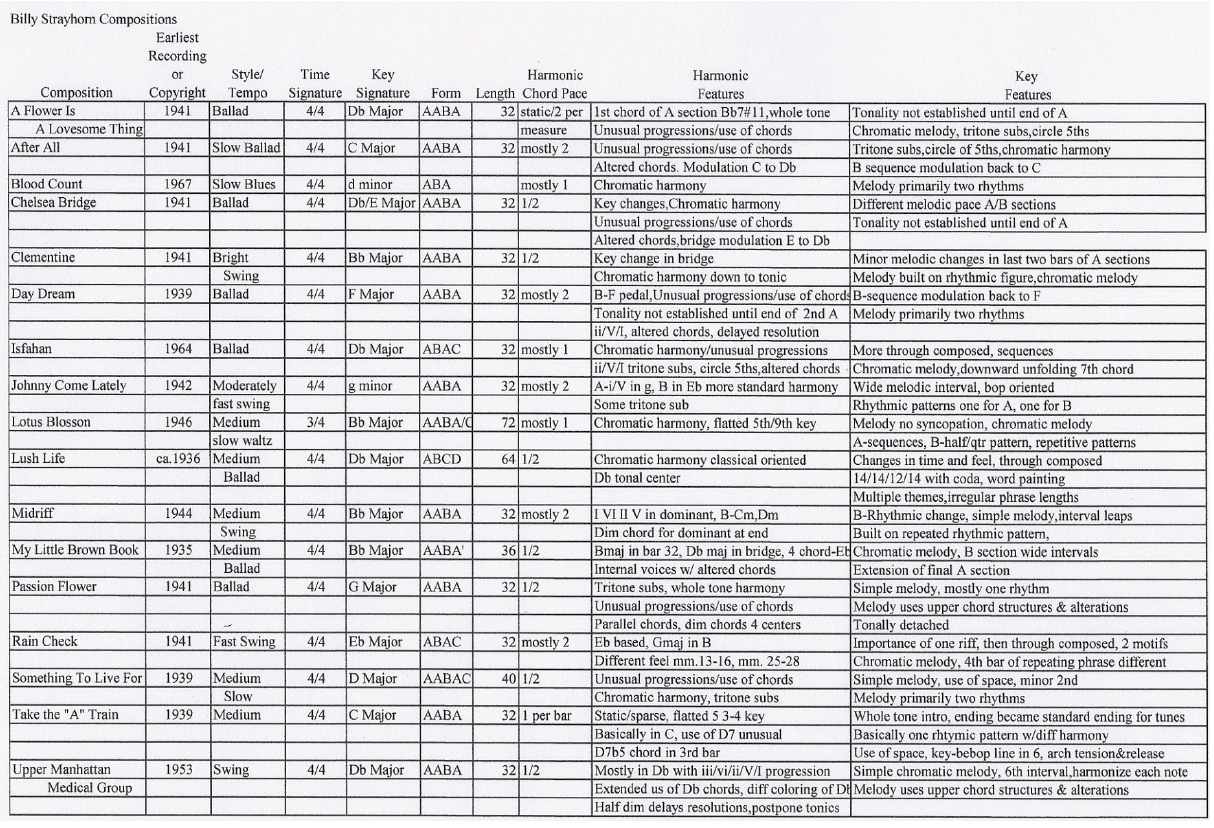

- Billy Strayhorn Compositions Summary Analysis

- Bill Murray Composition Summary Analysis

- Bill Evans’s Background

A musical Analysis of the Compositions of Bill Evans, Billy Strayhorn and Bill Murray

Sheet Music download available in our (YOUR) Library.

Bill Evans’s Background

Regarded as one of the most influential jazz pianists of all time, Bill Evans changed the way jazz piano is played and in the process influenced many of the best jazz pianists of the day including Herbie Hancock, Chick Corea, Keith Jarrett, Hampton Hawes, Steve Kuhn, Alan Broadbent, Denny Zeitlin, Paul Bley, Michel Petrucciani, and countless others. Gene Lees, noted jazz author, called him the most influential pianist of his generation, changing the approach to tone and harmony.1 James Lincoln Collier, another prominent jazz writer, says that Evans had the widest influence of any piano player since 1960.2 Evans rewrote “the language of modern jazz piano, incorporating harmonic devices derived from the music of French

impressionists and forging an ensemble style noted for its complex yet fluid rhythmic interplay.”

When Evans comes up in a jazz related discussion, two things are immediately discussed: his lyrical playing style and his harmonic approach to music. His tone was different and unique at the time when bebop was the reigning jazz style. Even today, Evans is used as a comparison by reviewers of modern day jazz piano recordings. One will regularly read the comment that the piano player being reviewed has been influenced by Bill Evans. Several of his trios are recognized as among the greatest jazz piano trios. He and the members of his trios changed the nature and playing style for piano trios where the members became a collective rather than just performing the traditional roles of piano, bass, and drums. These roles are common in today’s piano trios, but they were very inventive and new at the time Evans began using them.

In addition to being a great pianist, Evans was also a composer. While books, doctorial theses, and numerous articles have been written about Evans and his playing and improvising style, there has been little focus on his compositions and his composing style.

The purpose of a jazz composition is to set the stage for the improvisation that will follow the playing of the head. Jazz is about improvisation and not just about the composition or written notes. Evans wrote his tunes as a precursor to improvisation, but at the same time he firmly believed that the improvisation was highly dependent on whether or not the original form had something to say. As Harold Danko, a jazz artist, composer, and educator says,

Nowhere can we learn more about the musical language of Bill Evans than from his own compositions.. . . we can gain insight into how he arrived at the musical content through the process of composing. . . over the years, he used his own pieces as learning vehicles for improvising, and the present generation can follow his trail by investigating his very important compositional output.

Influences on Bill Evans.

Compositions are influenced by a person’s background and everything with which an individual comes into contact. This was certainly the case with Bill Evans. Born in Plainfield, New Jersey in 1929, Bill Evans began to study the piano at age six. Later on he also studied the violin and flute, but it was always the piano that interested him the most. Around five, Evans would listen to his older brother Harry’s piano lessons and then play precisely everything covered in the lessons. This led to Evans taking his own piano lessons and practicing as much as three hours each day.

Around seven, Evans also began to play the violin. While this was not his favorite instrument, from playing it, he may have learned how to make the piano sing which became a hallmark of his style. In the liner notes to “Bill Evans: The Complete Riverside Recordings,” Evans says; “Especially, I want my music to sing…it must have that wonderful feeling of singing.” This is an important characteristic of my own compositions and possibly the biggest influence of Evans on me.

From six to thirteen, Evans studied the classical piano repertoire but had no idea how the music was constructed. He won medals for playing Mozart and Schubert, and he also developed an appreciation for Delius, Debussy, Satie, Ravel, Grieg, Rachmaninoff, and Chopin. During this time, he continued to develop his sight reading skills playing only the notes on the page.

Somewhere around twelve he began to play in a high school rehearsal dance band with his brother and discovered the jazz idiom of substituting chords to change the harmony. His sight reading capabilities led to many playing opportunities around Plainfield. Even at this age, he also had a desire to know how the music was constructed and worked on his own to figure out the harmonies of compositions.

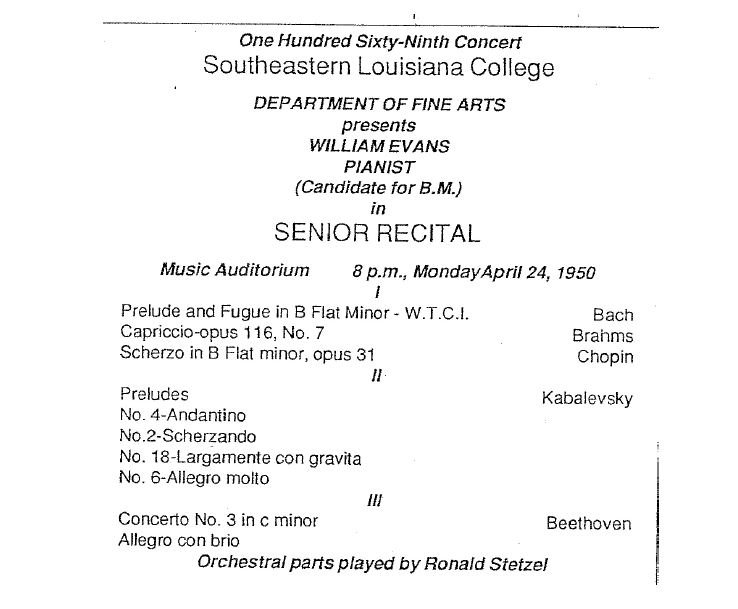

After graduating from high school, Evans received a scholarship to study music at Southeastern Louisiana College located fifty miles outside of New Orleans. Peter Pettinger, author of a Bill Evan’s biography, How My Heart Sings, says that this was very instrumental in the development of Evans’s style. In the early 1940s bebop was developing in New York City. Because of age and other things, Evans was not exposed to this style. By going many miles away from his home to study music, he was put in a place that allowed him to develop his own style and not be overly influenced by what was happening with bebop.

At Southeastern, Evans studied the classical piano repertoire. He played the sonatas of Mozart and Beethoven along with works by Schumann, Rachmaninoff, Debussy, Ravel, Gershwin, Villa-Lobos, Khachaturian, and Milhaud. Other composers studied included Johann Sebastian Bach, Chopin, Stravinsky, and Scriabin.

The program for his senior recital follows:

His study of classical composers was broad and diverse. He developed tremendous technique which he would use in later life, but it was always about the music not about using his technique to be flashy. For example, he said that playing Bach helped him to gain control over the tone that he would become famous for and to improve his contact with the keyboard.

Evans was very adept at drawing Western European compositional techniques into jazz and there are elements of Bach, Chopin, Debussy, and Ravel in his writing. He was able to take the harmonic connections from Debussy, Satie, and Ravel through Scriabin to Bartók and Milhaud and apply them to jazz. He learned from Debussy and Ravel the ambiguities of tonality, from

Bartók to employ wider chord intervals, and from Milhaud how to use bitonality. The compositional characteristics and techniques that he learned from studying the great classical composers would become evident in his compositions and playing.

The influence on Evans from classical composers can be readily seen in how he viewed them. In 1966 Evans and his brother, Harry, prepared a documentary on the nature of music, jazz, and improvisation. He called jazz the revival of the classical music of the 18th and 19th century when improvisation was common by such masters as Bach, Mozart, and Chopin and lamented improvisations disappearance over the years as more attention has been place on the written music. He felt that these great composers liked the freedom of improvisation. This feeling of freedom was one of the reasons that Evans moved toward jazz rather than becoming a classical concert pianist, but the influence of the great classical masters never left him.

At the same time Evans was studying the great classical composers at Southeastern Louisiana, he was also continuing to play regularly in the New Orleans area with a collegiate trio called the Casuals. He was playing and listening to a very different style of music than he was studying. After serving three years in the army and spending a year at his parent’s home to practice, he decided to enroll in 1955 at the Mannes School of Music in New York City to study composition because he felt that he did not know everything that he needed to know about music. He also looked forward to playing jazz in any place that he could find. All the time he was combining the entire scope of the musical traditions to which he had been exposed and developing his own style.

It was not only classical composers that influenced his playing and ultimately his composing. Bill Evans was a great listener and was able to absorb everything that he heard into his music. He learned from listening to many jazz pianists and jazz musicians. In an interview with the French magazine Jazz Times, Evans says,

From Nat “King” Cole I’d take rhythm and scarcity, from Dave Brubeck a particular voicing, from George Shearing also a voicing but of another kind, from Oscar Peterson a powerful swing, from Earl Hines a sense of structure. Bud Powell has it all, but even from him I wouldn’t take everything.

The biggest jazz piano influence on Evans was Nat “King” Cole. He was particularly enamored with Cole’s pianism, approach to melody, clarity and freshness of ideas, and tone. Another piano player who had a major impact on Evans was Lennie Tristano. While they were different in many ways, Evans identified with Tristano’s logical approach to music and the soundness of his construction. Logical structure is another hallmark of Evans’s compositions. He felt that he needed to build his music from the ground up and structure was very important to him. He wanted to understand the complete structure of a tune and what was happening theoretically.

Other jazz pianists that Evans said influenced him were Horace Silver and Sonny Clark. The jazz pianists previously mentioned represent a wide spectrum of styles and approaches. He also learned from all the jazzmen that he played with and listened to including Miles Davis, Dizzy Gillespie, Charlie Parker, and Stan Getz.

Evans incorporated what he wanted into his style and compositions. He was fond of saying that a person is “influenced by hundreds of people and things, and they all show up in his work. To fasten on to any one is ridiculous.” Evans learned from everyone.

Another very important influence on Evans was George Russell. Soon after graduating from Southeastern Louisiana and moving to New York City, he met Russell and subsequently studied and recorded with him. Russell had developed a theoretical work entitled The Chromatic Concept of Tonal Organization for Improvisation (for all instruments). The concept is based on Russell’s conviction that the Lydian scale with its raised fourth is more compatible with the tonality of a major scale than the major scale itself. The melodic and harmonic world of George Russell was original and was quickly absorbed by Bill Evans.

These concepts would appear regularly in Evans’s compositions and improvisations. Two examples of this are “Time Remembered,” in which all the major chords contain a #11 indicating the Lydian scale, and “Twelve Tone Tune Two,” where all the chords are major and the instructions to the improviser are to use the Lydian mode on all chords. Evans said that Russell composed pieces that sounded improvised and that one needs to understand all the elements of music theory to do this. One of Evans’s goals was to make his compositions sound spontaneous. The work of Russell was one of the starting points for Evans’s theories about phrasing, harmonic reduction, and the role of harmonic voice leading that were to become the hallmarks of his playing and composing.

Approach to Composition.

While Evans composed many tunes and studied composition, he did not consider himself a composer but thought of himself as a player who composed. In an interview with the Canadian jazz broadcaster Ted O’Reilly in August, 1980, Evans said that he didn’t really function regularly as a composer because a composer should compose everyday and he did not. He went on to say that at one time in his life he was in conflict with whether to follow the road of being a player or a composer and that he had resolved it. While he wanted to do some serious writing, he did not consider himself to be a full-time composer and certainly not more a composer than a player.

Most of what Evans wrote was done for the jazz idiom and in particular for the piano trio.

His compositions were used as the starting point for his improvisations. In the same interview noted above, Evans says that the compositions that he was writing as a Mannes student were in a variety of styles, but that they would not work in his current playing style because they were not designed for the spontaneity that is required in improvising.

How did Evans go about composing? In an interview with Don Bacon in September, 1975, Evans was asked whether or not his compositions were a spontaneous thing or did he spend hours at the piano working them out. Evans replied that he did both. For example, “Peri’s Scope” and “My Bells” just came to his head and he scribbled them down in a manuscript book. At times he would write the harmony first and the melody second as was the case with “Time Remembered.” At other times he sat and worked and worked making changes until he got what he wanted, as was the case with “Turn Out the Stars” and “Waltz for Debby.”

Evans decided on a particular style that was his own and he chose not to change just for the sake of change. Miles Davis reinvented himself regularly, but this was not what Bill Evans wanted to do. He traveled his own path. Once his approach was developed, he was no longer willing to expand his musical horizons, but chose to do a better job on what he liked and more fully explore the components of his style. He played and composed what he wanted to hear. In an interview on Marian McPartland’s “Piano Jazz Series,” Evans said that he did things to please himself and perfect his art. He was not particularly concerned with being popular. If it

happens, it happens. This feeling can also be extended to his compositions. McPartland sums up his approach by saying it must be like “swimming against the tide.”

Several factors are important to understanding his compositions. To begin with they are very logical. While many things may happen in them and they may go through many or all twelve tonal centers, they always return home and the listener hears them as being tonal and certainly not avant-garde although the chord structure may be anything but what is expected.

This was largely due to his structured approach. Evans needed to have a clear and complete understanding of the basic theoretical harmonic structure of anything on which he was working. He was known to spend hours studying the harmonic structure of standards that he wanted to use as part of his repertoire. This same attention to harmony is shown in all of his compositions. He had to be analytical to build things for himself. Structural harmony was a important concept for Evans. A common practice in jazz composition is to write a new melody over someone else’s chord changes. Evans never did this. Everything in his compositions was original and unique.

Bill Evans – Waltz For Debby

Billy Strayhorn’s Background

Throughout most of his career Billy Strayhorn was closely linked with Duke Ellington. While often referred to as Ellington’s assistant, Strayhorn wrote, composed, or updated about forty percent of Ellington’s 1939-1967 repertoire.38 Ellington referred to Strayhorn as his right arm.

. . . any time I was in the throes of debate with myself, harmonically or melodically, I would turn to Billy Strayhorn. We would talk, and then the whole world would come into focus. . . He was not, as he was often referred to by many, my alter ego. Billy Strayhorn was my right arm, my left arm, all the eyes in the back of my head, my brainwaves in his head, and his in mine.

This close association with Ellington made it a challenge for Strayhorn to receive the credit as a composer which he richly deserved. However, he was quite willing to stay in the background and let Ellington receive credit. This is not to take anything away from Duke Ellington who is one of the great American composers of all time. In recent years, research into Strayhorn’s work has solidified his position as a major composer and arranger.

Debate continues on the question of what would the Duke Ellington Orchestra have been like without the contributions of Billy Strayhorn. Bill Reed, in his book Hot From Harlem, comments that without Strayhorn’s contribution the Ellington legend that we know would probably not exist. On the other hand, critics such as James Lincoln Collier and Leonard Feather have slightly different viewpoints as to his importance. One Strayhorn scholar, Andrew Homzy, Associate Professor of Music at Concordia University in Montreal, says that the relationship between Ellington and Strayhorn was similar to the relationship between Haydn and Mozart, “where you have the master establishing a style, and then the youngster coming in absorbing that, expanding on it, and taking it in another direction—and then the youngster dying, and the master picking up what the youngster had taught.” In any case, more scholars and critics are recognizing the value of Strayhorn to the Duke Ellington Orchestra.

Influence on Billy Strayhorn:

Billy Strayhorn grew up in Pittsburgh, Pennsylvania in a poorer section of town in a four- room house without electricity on an unpaved street. Early on he became very interested in music, but his family did not have the means to get him a piano or any other musical instrument. Wanting to buy a piano while in grade school, he began to sell newspaper on a street corner where Pennfield Drugs was located. This ultimately led to a job at Pennfield Drugs where Strayhorn would continue to work during and after finishing high school. By selling newspapers and working at Pennfield Drugs, Strayhorn was able to buy his piano while still in grade school. He also paid for his own music and piano lessons. A boyhood friend, Robert Conaway, recalls that Strayhorn spent all of his money buying music of all kinds. His stack of music was about four and a half feet from the floor. He played and studied this music extensively. Strayhorn said that after he bought his piano: “I started to study, and the more I learned, the more I wanted to learn.” Strayhorn attended Westinghouse High, a public school endowed by George Westinghouse of the Westinghouse Company. Westinghouse High had a swing band but Strayhorn was not interested in it because he wanted to become a concert pianist. He concentrated on the classical concert repertoire. In high school, he took classical piano lessons and studied harmony. Eventually he became the pianist for the Westinghouse High Senior Orchestra. After a performance of Edvard Grieg’s Piano Concerto in A Minor, op. 16, Carl McVicker, the school’s band director, commented: “The orchestra may have been a group of students, but Billy Strayhorn was a professional artist.”

At this time Strayhorn also began to compose. One early piece that he brought to the Westinghouse Orchestra Club was “Valse,” a piano waltz. Its rippling melodic lines and graceful modulations bear the mark of Strayhorn’s future compositions. The piece uses musical elements such as the shifting among minor keys that Chopin often used. Around the same time, he wrote a piece entitled Concerto for Piano and Percussion. The piece, heavily influenced by George Gershwin was completely orchestrated with parts for each instrument and was performed at Strayhorn’s graduation. Many Westinghouse students thought that they were listening to Gershwin’s Rhapsody in Blue. This piece also foreshadowed musical elements that appeared in later Strayhorn compositions: variations of popular music style phrases over chromatic harmonies, syncopated rhythms, repeated rhythmic patterns, hemiolas, and the use of minor chords with a major seventh. Strayhorn looked into going to college but did not go. His friend, Harry Henforth, said:

Billy looked into colleges but was discouraged because of his race and could not get the necessary financial aid. The very idea of a black concert pianist was considered unthinkable. It has nothing to do with Billy’s considerable talent.

While continuing to work at Pennfields Drug after graduating from high school, Strayhorn stayed active with Westinghouse High groups and put together a review called Fantastic Rhythm which featured a chorus of dancing girls and a small band which he led. All ten tunes and their words were written by Strayhorn and included “My Little Brown Book” which would become famous later when recorded by the Ellington Orchestra. In addition, he arranged the music for a twelve- piece orchestra. The review was popular in the Pittsburgh area and furthered Strayhorn’s local reputation. Once again these compositions were precursors for what was to come.

Hoping to foster his classical career he attended The Pittsburgh Musical Institute for two months in 1936 to study piano and music theory, but left after the sudden death of his teacher, Charles Boyd. Strayhorn said that there was no one else that could teach him. It was around this time that Strayhorn recognized that there were limited opportunities for a black concert pianist and he began to concentrate his composing efforts on jazz pieces rather than classical and theater songs. During this same period, he wrote one of his most famous pieces, “Lush Life,” which demonstrated his love of densely chromatic music.

Billy Strayhorn and the Duke Ellington Orchestra:

The most significant happening in Strayhorn’s career occurred in December, 1938, when a friend arranged a meeting with Duke Ellington back stage at the Stanley Theater in Pittsburgh. The results of this meeting led to a twenty-eight-year association with Ellington that changed musical history in many ways. Ellington, not exactly certain how to use Strayhorn, basically hired him to write lyrics for songs. This quickly gave way to arranging assignments, new compositions, and ultimately a collaboration between two very different musicians that is unparalleled in musical history.

A big break for Strayhorn occurred in 1941 during the disagreement between the American Society of Composers and Publishers (ASCAP) and the radio networks. Radio networks refused to broadcast music by any ASCAP member, which meant that none of Ellington’s compositions could be played. Needing a new repertoire, he asked Strayhorn and Ellington’s son, Mercer, who were not members of ASCAP, to compose new pieces that could be recorded. During this time some of Strayhorn’s most well-known tunes were written. Among them were “Take the A Train,” “Chelsea Bridge,” “Clementine,” “A Flower Is a Lovesome Thing,” “After All,” “Love Like This Can’t Last,” and “Rain Check.” “Take the A Train” became one of his most famous and frequently recorded tunes and ultimately became the theme of the Duke Ellington Orchestra. “Chelsea Bridge” was the first piece to draw attention of others to Strayhorn’s work.

Strayhorn continued to compose and arrange for the Duke Ellington Orchestra until his death. He collaborated with Ellington on all types of works including Broadway pieces and Ellington’s religious and longer pieces. He also made attempts to be more independent from Ellington and to do things on his own with differing degrees of success, but it became clear that working with Ellington was the best for him. A heavy drinker and smoker, Strayhorn was diagnosed with cancer of the esophagus in 1964. His health worsened over the next several years and he died on May 31, 1967, at the age of fifty-one. During the last months of his life, he completed another of his well known pieces, “Blood Count,” which is generally considered to be his last original work. This brooding piece in a minor key, which Strayhorn seldom used, is composed with musical metaphors expressing openly Strayhorn’s feelings of sadness, frustration, and failure.

Strayhorn’s death impacted Ellington immensely. His feelings for Billy Strayhorn were communicated strongly in Ellington’s eulogy at Strayhorn’s funeral. He clearly recognized his appreciation for what Strayhorn had done for him. Several months after his death a memorial album, And His Mother Called Him Bill, was recorded by the Ellington Orchestra. This album contained a number of Strayhorn’s most well-known tunes. The last tune on the album is a piano solo by Ellington of “Lotus Blossom” which was picked up after a session was completed and unknown to Ellington the studio tape recorders were not turned off. This solemn, tormented, intimate performance by Ellington with its flubbed notes and studio noises serves as a coda closure. Ellington recovered, went on to tour and compose again with more drive. He said; “I’m writing more than ever now. I have to. Billy Strayhorn left that big yawning void.”

For all practical purposes, Strayhorn was a self taught musical genius. No doubt his long association with Ellington, one of the greatest American composers, was a true learning experience, but he also educated Ellington and made Ellington better as well. His association with Ellington gave him a musical home where his ability to combine his classical ambitions and jazz existed in the same place. His compositions are structurally and harmonically among the most sophisticated in the jazz repertoire.

They fused compositional techniques from the European classical music tradition with American jazz concepts that were firmly rooted in his African-American heritage. His compositions foreshadowed the cool jazz orchestrations Gil Evans and Gerry Mulligan did for Miles Davis in the late 1940s and the third stream movement of the 1950s. In additions to Evans and Mulligan, his compositions were important to notables such as Dizzy Gillespie, John Lewis, Benny Carter, Slide Hampton, Billy May, Bill Finnegan, and Ralph Burns.

Comments from these musicians show the impact that Strayhorn had on the jazz community. Gil Evans said that once he heard “Chelsea Bridge” all he tried to do was to do what Strayhorn did. Benny Carter stated that Strayhorn’s composition were complete and not just riffs or chord changes which made others think a little differently about what they were doing. Gerry Mulligan commented that even though what he was doing was sophisticated, it didn’t sound complicated to the ear at all and seemed completely natural and emotional. According to Willie Ruff, Strayhorn never wrote cliches and his music was so unusual that it could catch you by surprise the first time that you saw it.

Lawrence Brown, a longtime member of the Ellington Orchestra, says that Strayhorn was one of the most under-rated musicians that he had ever known. He considered him to be a terrific musician whose works all had deep feelings behind them.

Strayhorn’s most important compositional and arranging concept was what he called “thinking with the ear,” where his approach was to express emotion rather than to be worried about theory. It must sound good. In an interview with Bill Coss in 1962, talking about his composition and arranging style, he said:

I have a general rule about (writing). Rimski-Korsakov is the one who said it: all parts should lie easily under the fingers. That’s my first rule: to write something a guy can play. Otherwise, it will never be natural, or as wonderful, as something that does lie under his fingers. . .. You have to find the right color. . .. Color is what it is, and you know when you get it.

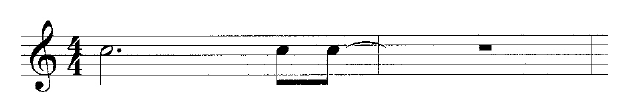

DUKE ELLINGTON “Daydream” BILLY STRAYHORN (1968)

Bill Evans Compositional Style

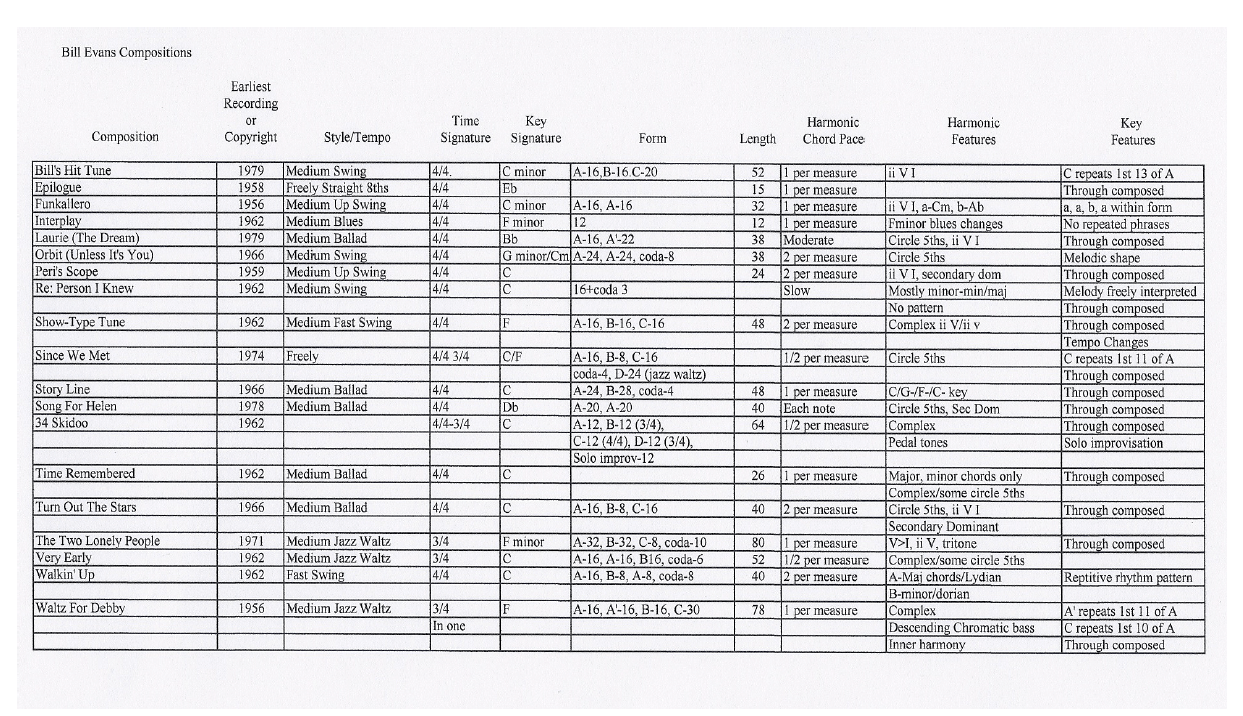

The most comprehensive collection of Bill Evans’s compositions is the Bill Evans Fake Book transcribed and edited by Pascal Wetzel from Bill Evans’s recordings and published by Ludlow Music. This book contains 59 of his original tunes along with the lyrical version to sixteen of them. During his career, only 52 of the 59 tunes were recorded. In making the lead sheets, Wetzel used the original lead sheets or published sheet music whenever he could.

Transcriptions from recordings were also used if necessary and in this case, the lead sheet follows the latest recording in order to show the evolution over time. Because of Evans’s interest in harmony, Wetzel chose to be more precise than the typical lead sheet by adding counterlines, codas, and chord extensions including passing chords and alternative chords. The original key was used, but it was not unusual for Evans to play a piece in different keys as transposition was one of his favorite musical devices.

A review was made of all of the compositions in this book to determine if they shared common characteristics that could be classified as the Bill Evans’s composing style. Only the instrumental versions were considered. The following categories were evaluated in each of the tunes: date of first recording or copyright whichever was earlier, style, time signature, key signature, form, length, harmonic chord pace, harmonic features, and melodic features. As previously noted, a select number of these compositions were used to develop the characteristics to be used for comparison. Appendix 2 contains this information.

While Evans’s piano technique was second to none, he was not interested in using his technique just to show off or impress someone. His focus was on the music and the expression he wanted. Much of his composing was done to provide material for his own playing and not to provide material for others to play. He was considered to be a master of the jazz waltz and his interpretations of ballads were legendary. While he could play the blues, he was not known as a blues piano player or one who was heavily influenced by the blues. These factors all show up in his compositions.

Shown below are the styles for his compositions.

Style Compositions

| Jazz Waltz | 10 |

| Ballad | 16 |

| Medium Swing | 8 |

| Medium Up Swing | 9 |

| Fast Swing | 3 |

| Blues | 2 |

| Other | 7 |

His focus was on slow to medium-tempo tunes that allowed him more room for the lyricism, tone, expression, and harmony that he enjoyed so much. Two of his most well-known tunes, “Very Early” and “Waltz for Debby” are both jazz waltzes. Two other well-known tunes are ballads, “Time Remembered” and “Turn Out the Stars,” further documenting what people like about his work. The two blues-oriented pieces were written in the early part of his career. Only one of them was recorded. As he matured using the blues form for composing was clearly not part of his thought process. Only three tunes, “Displacement,” “One for Helen,” and “Fun Ride” are marked as fast swing. The fast tempos favored by many jazz musicians were not a major part of his repertoire.

In composing, Evans liked to use 3/4 meter to “articulate the more tender and ruminative side of his artistic character.” Interestingly, most of the jazz waltzes were for or about a female in his life. Evans was also known to change meter within tunes such as: “Comrade Conrad,” “Five,” “Since We Met,” and “34 Skidoo.” The meter change allowed him to change the mood of the tunes completely. “Waltz for Debby,” is a jazz waltz, but he also played and recorded this tune in 4/4.

Form is very important for improvising in jazz as it is a key tool in keeping an improvising ensemble together. When a group is improvising and not reading music, the form helps keep the players in the same place and together. The most common jazz forms are the 12-bar blues and two forms common in the so-called Great American Songbook of standards, AABA and ABAB, where A and B are eight bars long. For many standards, the melody and harmony for the A sections are either the same or very similar in the AABA form and the same can be said for the A and B sections in the ABAB model.

There are two ways of looking at these forms: melodically and harmonically. Most of Bill Evans’s tunes do not conform to either of the traditional standard forms either melodically or harmonically. Only “These Things Called Changes,” which takes the chord changes of “What Is This Thing Called Love” as a basis, even roughly corresponds to the AABA form.

A 32 bar form is also very unlikely for a Bill Evans composition. Only four of them are exactly 32 bars long, but none of them conforms to the traditional models of section lengths.

There is no common length for the compositions; they range from 12 to 80 measures. A number of sections are 16 measures long, but this should not be interpreted to be the standard section length. Another feature of his compositions is the use of codas or tag endings. Eighteen pieces contain this feature. There is nothing common about the form of his compositions. A more detail analysis of form can be found in Appendix 2.

From a melodic perspective, 48 of the 59 tunes can be considered to be through composed in that the melody does not repeat itself in the composition. For those with some part of the melody repeated, it is unlikely that the entire melody will be repeated exactly in a subsequent section. For example, in “Bill’s Hit Tune,” the form is A (16) B (16) C (20) where the first 13 measures of C are the first 13 measures of A. If one looks at the sections within most of the tunes with some repetition, there is little or no repetition of phrases in the sections themselves. Melodically, every note is dependent on its attached harmony.

In most of the lead sheets jazz musicians use, phrase lengths of four and eight measures are most common and their improvisations reflect this. In his playing, Evans seemed to think in terms of much larger phrases such as thirty-two bars or longer. His compositions with their through composed nature reflect this. It is often difficult to determine exactly what the phrase length is. One of his bassists, Chuck Israel, says, “His phrases start and end in ever-changing places, often crossing the boundaries between one section of a piece and another.”

For jazz compositions and thus improvisations, the key signature gives a good indication of the primary tonal center for a tune. What role does the key signature play in his compositions? The melancholy nature of much of his work would indicate the heavy use of minor keys. Fourteen of the works are in a minor key. In the interview with Marian McPartland, he indicated that two of his favorite keys were A and E because of the overtones and resonance they provided. Interestingly, only “Remembering the Rain,” is in A and none are in E.

Shown below are the initial key signatures for the compositions by tonal center.

Key Signatures for Bill Evans Compositions

| Key | Minor | Major |

| C | 6 | 19 |

| Db | 3 | |

| D | 1 | |

| Eb | 3 | 4 |

| F | 6 | 1 |

| G | 1 | 4 |

| Ab | 2 | |

| A | 1 | |

| Bb | 2 | 3 |

| B | 1 |

From looking at the above table, it would appear that the favorite key for Evans was C and most of his tunes would sound as if they are in C and that C would be the primary key for improvisation. This is very misleading when the compositions and harmony are examined more closely since it is unlikely that they will remain in one tonal center or even a closely related one. The term tonal center is used rather than indicating a key change because it is very difficult to determine whether the key has actually changed, but it can clearly be seen that the tonal centers are changing.

The key signature is likely to be only a starting and maybe an ending place as tunes that start in one key may end in another key. For example, the key signature for “Very Early” is C and the first chord is a C major chord, but the last chord is B major. Similarly, for “Time Remembered” the key signature is once again C but the last chord is C minor. It is often very difficult to determine the primary tonal center of a Bill Evans composition, and certainly the key signature is not a good determinant.

When people think of Evans’s music, harmony is a key component. Are there any common harmonic features in his composing style? Two concepts were explored in this regard: harmonic chord pace or the number of chord changes per measure and the existence of harmonic patterns such as ii V I progressions or circle of 5th patterns.

Bill Evans was renowned for spending hours working through chord changes and making sure that the chord voicings were what he wanted. The inner voicings and voice leading that were very important to him might indicate a faster harmonic pace. The complexity of harmony can often be determined by looking at how frequently the chords change. For those tunes where there was a clear chord change pattern, the following occurred.

| Chords per Measure | Compositions |

| One | 14 |

| One or two | 14 |

| Two Threee or four | 20 2 |

This pace is not any faster than many other tunes in the jazz repertoire or the Great American standard songbook.

The major harmonic difference between a Bill Evans tune and many others played by jazz musicians is in the quality of the chord and where the chord moves. Two very common patterns in the jazz literature are ii V I(i) or I vi ii V I (Rhythm Changes). While a ii V I pattern exists in many compositions, it is not the predominant pattern in other than a few pieces such as “Bill’s Hit Tune,” “Turn Out The Stars,” and “The Two Lonely People.” This pattern was also more common in his earlier compositions and became less frequent in later ones.

Two harmonic devices are frequently used in his work: use of the circle of 5ths and the secondary dominant. There is a clear usage of extended circle of 5ths patterns in twenty-five tunes. A good example of the extended use of this pattern is the first six measures of “Turn Out The Stars.” The chord progression is:

| Bm7(b5) E13(b9 ) | Am(maj7) Am7 | Dm7 G7(#9) | Cmaj7 | Fm7 Bb7 | Ebmaj7 | This is almost a complete circle.

The usage is also often different from the circle of 5ths pattern that exists in the ii V I pattern. The quality of the chords is not always the traditional minor/dominant/major chord pattern as in the above example. Other examples are in “Time Remembered” where one of the chord progressions is:

| Am9 | Dm9 | Gm7 | Cm7 | Fm9 |

Each chord lasts for one measure. Another example is in “Waltz for Debby” where measures 13- 20 containing the following progression:

| Am7 | Dm7 | Gm7 | C7 | Am7 | Dm7 | Gm7 | C7 |

These progressions from his best known tunes are representative of the many nonstandard circle of 5th patterns Evans used. The use of the secondary dominant was also an important feature and a technique he used for moving through different key centers.

His first composition, “Very Early,” shows the importance of this concept. The chords of the A section are:

| Cmaj7 | Bb9 | Ebmaj7 | Ab7(#9) | Dbmaj7 | G7 | Cmaj7 |

|Bb9(b5) | Dmaj7 | Am7 | F#m7 | B7(b9) | Em7 | Ab7 | Dbmaj7 | G+7 |

In these 16 measures, there are five V>I(i) movements. This same kind of pattern can be found in many of his other compositions.

The use of these techniques makes it possible for Evans to explore various tonal centers and often go through every one of the twelve tonal centers. Two examples of such compositions are “Comrade Conrad” and “Fun Ride.” While the quality of the chord may change and numerous alterations to the chords may occur, because of the always present V>I relationship in root movement, the compositions sound very tonal and not what one might expect from the harmonic direction he is taking. This root movement results in the feeling that while he explores many tonal areas, his work always seems to return home.

“Time Remembered” is also a prime example of how Evans used nonstandard harmonies.

The tune uses only minor and major chords. There are no dominant chords. In jazz, the dominant chord is a key chord since it is the most easily altered chord and the one for which substitutions are often made. These techniques provide much of the color, tension and release that is common in jazz. “Time Remembered” becomes an exercise in using the dorian scale on the minor chords and the lydian scale on the major chords for improvisation. By using modes, Evans is still able to achieve the desired tension and release.

Chuck Israels says that his harmonies were less based on chords than a “piling up of contrapuntal lines in which the tension and release phase between the melody and the secondary voices was exquisitely shaded by his control of pianistic touch.” This comment relates directly to the inner voices and voice leading that are a major part of Evans’s work. The progression of chords is often very chromatic but the tonality of the piece is always there. Tim Murphy, a jazz pianist and educator, equates Evans’s harmony to being the figured bass of the jazz world. Always expect surprises from the harmonies that Bill Evans used.

Rhythm was also important to his work and particularly rhythmic displacement or layering duples or triples over the meter of the chords. The rhythmic construction was as important to him as was the harmonic construction. Jeff Antoniuk, a jazz saxophonist and educator related the following conversation that he had with the prominent jazz saxophonist, Joe Lovano. Lovano had the opportunity to play with Evans and as he was playing he thought that he was in wrong place in the form and always behind. This would be very unusual for a jazz musician of Lovano’s caliber. What he learned was that Evans was anticipating the chord changes well in advance of the typical anticipation of chord changes on the ‘and’ before the chord change. He really was not behind. Evans was displacing harmony to impact rhythms and improvisations. One of Evans’s compositions “Displacement” clearly shows this concept where chord changes often occur on beat 4 rather than on beat 1.

Other rhythmic displacement devices he used were polyrhythms and cross meters. These first appeared in “Peri’s Scope,” which is written is 4/4 but has a three in a bar feel.81 This concept of alternating meters can be seen in “Five” where the piece is based on 5 against 4 and 4 against 3 rhythms and “G Waltz,” which makes use of 4 against 3 and 3 against 2. Many other pieces employ 3 against 2 and anticipation of the beat.

Evans was one of the first jazz musicians to base a composition on a twelve-tone row. Familiar with the works of Arnold Schönberg, he wrote two pieces using this concept, “Twelve Tone Tune” known as “T.T.T.” and “Twelve Tone Tune Two” or “T.T.T.T.” Evans said that this was strictly a challenge as he normally wouldn’t want to base a composition on this concept other than to stretch himself. “T.T.T.” is 12 measures and 36 notes long. Each row is four measures long. When he harmonized the row, he used diatonic harmony because of the difficulty of improvising over the row itself. He chose to personalize the row as many other composers had done by ignoring the rules that no note could be repeated before the full row is used and that no attempt to use conventional tonality to harmonize the row would occur. While consideration was give to improvising on the row, it proved too difficult.

The head of “T.T.T.T.” expanded the concept of a tone row to 60 notes over 12 measures which was then repeated. The harmonization was also different in that all major chords were used. The major chords for improvisations for the 24 measures were:

| G | F | Eb | Db | C | Bb | Ab | Gb | B | Bb |A | Ab|

| G | A | B | C# | C | D | E | F# | B | C | C#| D |

At a medium up tempo, this progression is a challenge for even the best improviser.

Another interesting Evans’s composition is “Fudgesicle Built For Four” written earlier in his career, which shows the diversity of his compositional capabilities. The head of this piece is a four-part fugue for guitar, piano, bass, and tenor sax. While the head is very complex, improvisation is done over rhythm changes.

Did the compositions of the mature Bill Evans change from the compositions of Evans in his early years? While most assuredly they did to some extent, many of the techniques that appeared in “Very Early,” which was written when he was a student at Southeastern Louisiana, appear in many later compositions. Two areas that became more refined over the years are the increasing importance of the inner voice chord progressions and a more sophisticated approach to rhythmic construction and displacement.

All Evans’s compositions show that he had the ability to do whatever he wanted and to use a wide variety of musical techniques to accomplish his objective. They are for the most part built on one main idea which could be a pedal point, a certain chord structure, a rhythmic pattern, a three- or four-note pattern, tempo changes, relationships between seemingly unrelated keys, tone rows, etc., etc., etc…… In all cases they are complex, challenging, and interesting. Over the course of his life, his concept of harmony continued to develop. Each development laid the stage for the next development. As his biographer, Peter Pettinger says:

This essentially harmonic world was enhanced by inner and outer moving parts, comments and colorings: a note that began as a chromatic passing note might be transferred into the chord itself, which then emerged as a fresh voicing. The evolution spanned his whole life and was continuing to develop at his death.

Many things can be said about the compositions of Bill Evans. In an interview, he said: “I believe all music is romantic romanticism handled with discipline is the most beautiful kind of beauty.” This statement sums up his compositions succinctly. Overall his compositions were closely tied to his improvisational style and few of them have become tunes that are performed by other jazz artists. Even though most of the compositions have interesting melodies, it is the harmony that really distinguishes them. His compositions are complete melodically, harmonically, and rhythmically. Sean Petrahn says the following:

One does not have to change a single note or chord in a Bill Evans tune; you would destroy the composition. Would you change a chord in a Beethoven Sonata, or the Bartok “Improvisations”? I doubt it. It takes great humility to play the music of Bill Evans because you must leave it alone; you must leave your ego in the closet and play ‘as written’.

Maybe this is the real reason that his music is not played more often rather than its complexity and challenging nature. Most jazz musicians don’t like to play things just as they are written.

Eddie Gomez, an Evans bassist for eleven years, said this of his friend: “Bill Evans was articulate, forthright, gentle, majestic, witty, and very supportive. His goal was to make music that balanced passion and intellect that spoke to the heart.” There is no better way to sum up his compositions. Bill Evans is clearly recognized as one of the most influential jazz pianist in history but this statement has not yet been associated with him as a composer. Only time will tell, but when one looks carefully at his work it becomes quite apparent that he was a composer extraordinaire. The overall sound of his music has certainly influenced me.

Billy Strayhorn’s Compositional Style

Most experts agree that many of Strayhorn’s composition characteristics vary from those of Ellington even though they were so closely associated with each other and composed many pieces jointly. These differences are not part of this paper, but they complicate an analysis of Strayhorn’s work. Only those pieces specifically composed by Strayhorn and which are included in a fake book have been considered.

Another complicating factor is that most of Strayhorn’s compositions were written with a small ensemble or big band in mind. Strayhorn was a master arranger and consequently just reviewing the lead sheets for compositional characteristics has the potential to be somewhat misleading. In composing, Strayhorn was considering how the piece would sound using an ensemble and how he would arrange it for that ensemble. The lead sheet was a starting place for a total arrangement. Strayhorn explained his approach to writing music as follows:

Arrangers and composers must see the piece of which they are working as a complete entity. They ought to use four or five dimensions and see all around the material—over, above, and under it, and on the sides two. Then the job becomes one of transposing the physical picture into an integral and complete mental picture. . . I endorse what I might term thinking with the ear—the intuitive feeling again, but I can’t overstress its importance.

While the total picture was the hallmark of Strayhorn’s style, for purposes of this paper, only the lead sheets of his compositions were reviewed for stylistic characteristics.

It is fully recognized that analyzing a limited number of compositions can lead to misleading conclusions of a composer’s works, but this paper is not about the total works of Strayhorn. It is about the works that may have influenced Bill Murray as a composer.

Interestingly, these pieces are also the focus of many musical examples used by Walter van de Leur in his comprehensive analysis of Strayhorn’s music, Something to Live For: The Music of Billy Strayhorn. They are also the Strayhorn tunes most recorded by other musicians. Thus, they are the ones that I would have been most likely to have heard in listening to jazz.

Most of the tunes that appear in the fake books used for this analysis come from early in his career as shown below.

| Recorded | ||

| or | ||

| Copyright | ||

| Year | Compositions | |

| Pre-Ellington 1935- 1939 | 3 | |

| Ellington 1939-1949 | 2 | |

| ASCAP Dispute 1941 | 6 | |

| 1942-1949 | 3 | |

| 1950s | 1 | |

| 1960s | 2 |

Why this occurred is outside the scope of this paper, but it shows that what has become known as the Strayhorn touch developed early in his career. Appendix 2 contains an analytical summary of the tunes in this analysis.

From a style perspective, Strayhorn’s ballads are some of his best known works.

The following table categorizes the pieces analyzed by style and tempo.

| Style | Compositions |

| Ballad | 8 |

| Moderate Swing | 4 |

| Bright Swing | 3 |

| Jazz Waltz Other | 1 1 |

His ballads which are often referred to as ‘mood pieces’ are and include “Chelsea Bridge,” “Daydream,” “Passion Flower,” “A Flower Is a Lovesome Thing,” “Lush Life,” and “Lotus Blossom.” While not a ballad, “Blood Count” also falls into this style. Most of his compositions in the fake books fall into the slow to medium tempo range. Up tempo was not his primary forte. Noticeably absent from this list are any pieces in the blues idiom. While Strayhorn wrote several pieces based on the blues form, they are not among his most prominent compositions and the blues was not a key idiom for him. His world was much more that of sophisticated show business and top class nightclubs. “Take the A Train,” one of his most well-known pieces, is considered by most to be rather atypical of his style.

One of the notable elements of Strayhorn’s compositions is their lyrical and original melodies. Several of the works being analyzed were written specifically for alto saxophonist Johnny Hodges. His alto sax sound and Strayhorn’s writing worked together very well.

Composing for individual musicians, a trait that Strayhorn picked up from Ellington, became a common element in Strayhorn’s compositions after he joined Ellington.

In terms of structure, most of the pieces follow the conventional AABA form of Tin Pan Alley as shown below:

| Form | Compositions |

| ABA | 1 |

| AABA | 11 |

| ABAC | 2 |

| AABAC | 2 |

| Other | 1 |

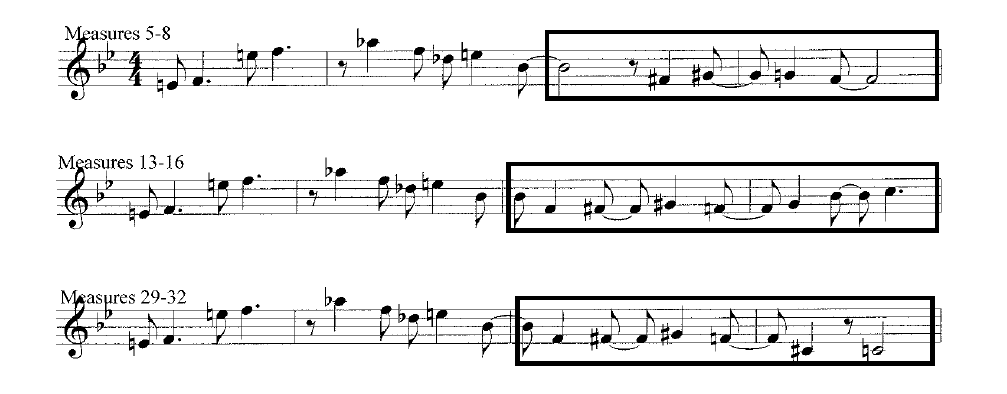

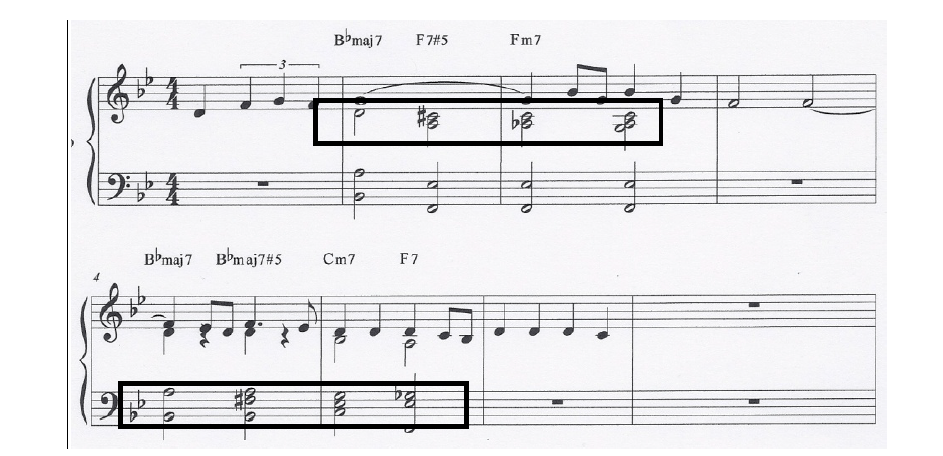

However, most of the A sections are not exact repeats of each other. Slight differences occur in pitch, rhythm, or harmony as is shown in the following example from “Clementine.” The differences are highlighted with the boxes around the appropriate measures.

While these are subtle changes, most of Strayhorn’s music would not be considered to be through composed as was the case with Bill Evans. “Lush Live” with its changing moods and feel would be an exception and is through composed. The objective of the B section is to provide contrast to the A section, and Strayhorn did this particularly well. He regularly takes the listener far away from what was heard in the A sections. He does this using such elements as going to a key remote away from the key of the A section, by changing the rhythmic feel, or making the bridge a sequential motif to take the piece from where the A section ended back to the original key. The length of most of the pieces follows the standard 32 bars for AABA forms. The exceptions tend to be his pre-Ellington pieces.

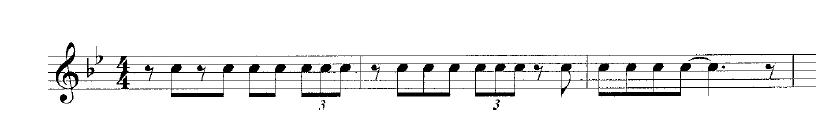

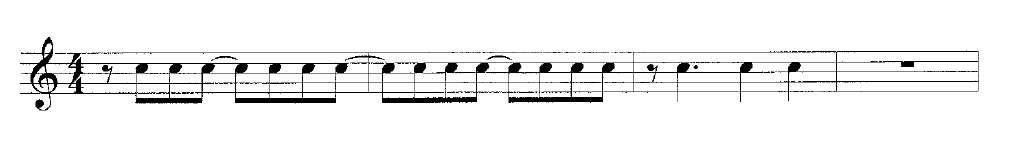

Strayhorn based certain pieces on one or two motifs. Examples of this are “Blood Count,” “Day Dream,” “Johnny Come Lately,” “Lotus Blossom,” “Midriff,” “Passion Flower,” “Raincheck,” “Something to Live For,” and “Take the A Train.” The following is the rhythmic pattern used in five of the six four-bar phrases in the A section of “Midriff,” yet the piece does not seem repetitive because of what Strayhorn does with the sixth-four bar phrase of the A section and the entire B section. In this piece, the pitches used are also the same.

In “Raincheck,” Strayhorn uses the following rhythmic pattern in six out of the eight four-bar phrases. Once again the same notes are used in these phrases.

One of Strayhorn’s favorite rhythmic patterns is shown below.

Most of “Passion Flower” uses this pattern at different pitches. In his later works such as “Upper Manhattan Medical Group” he began to be more flexible in his rhythmic approach and let the melody flow more freely over the harmony. While he used repeated rhythmic patterns in many compositions, what Strayhorn did with the remaining phrases and harmony always makes the pieces interesting and a listener does not have the feeling of extensive repetition.

Given the consistency in form and use of repeated rhythmic patterns, what makes Strayhorn’ music interesting? It comes down to how he used a variety of harmonic, melodic, and rhythmic motifs to bring cohesion to a piece and to unify it. The overall structure of many of his compositions was arch like and was achieved by the gradual build up and release of tension. A good example of this is “Take the A Train.”

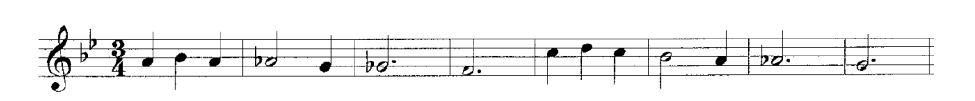

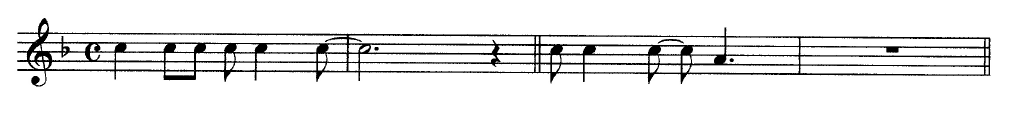

Another musical element he used was melodic chromaticism particularly the interval of a minor second. Ten of the analyzed melodies, “A Flower Is a Lovesome Thing,” “After All,” “Clementine,” “Isfahan,” “Lotus Blossom,” “Lush Life,” “My Little Brown Book,” “Rain Check,” “Something to Live For,” and “Upper Manhattan Medical Group” can be classified as basically chromatic melodies. For example, “A Flower Is a Lovesome Thing” employs eleven of the twelve notes of the chromatic scale. The first eight bars of “Lotus Blossom” as shown below also demonstrate how Strayhorn used chromatic melodies. These melodies when combined with the harmony used bring about the Strayhorn sound.

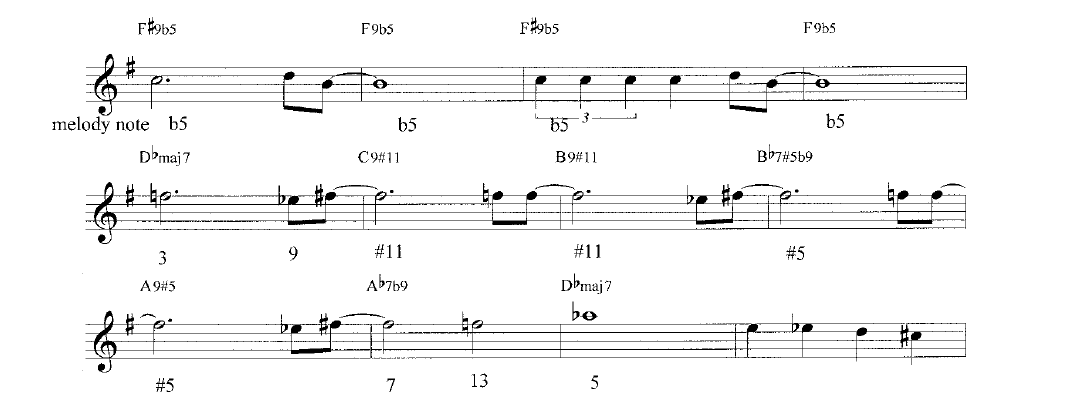

Another melodic tool was the use of upper chord structure notes and altered notes as the basis for the melodies. The following phrases from “Passion Flower” demonstrate how Strayhorn used these notes for the basis of the melody.

Many times he voiced the melody to move at a dissonant interval with one or more of the chord tones in the accompaniment. The melody was often a minor or major ninth above the first or second voice of the accompaniment chord. A good example of how he used this dissonant movement occurs in the first six bars of “My Little Brown Book.” As shown below in the blocked areas, he uses alterations of chords to change the color of the sound and provide the chromatic internal counterpoint that is a regular part of his sound.

One of the hallmarks of the Strayhorn sound is how he used harmony. While he was fully versed in traditional classical harmony as well as that of Tin Pan Alley, ultimately he was more concerned about the sound than any harmonic rules. However, as his work matured, he made less use of unexpected chords that occurred in early pieces such as “Something to Live For.” Nevertheless, every tune being analyzed contains unusual chord progressions or uses of chords. Harmonic elements are a key part of the Strayhorn sound.

Strayhorn liked to compose in keys containing flats leading to a more tranquil, subdued, laid back sound as opposed to the brighter timbres of the keys containing sharps. Keys for the analyzed pieces are shown below:

| Key Signature | Compositions |

| C major | 2 |

| Db major | 5 |

| D major | 1 |

| Eb major | 1 |

| F major | 1 |

| G major | 1 |

| Bb major | 4 |

| d minor/D major | 1 |

| g minor | 1 |

Strayhorn was not known for writing much in minor keys although one of his more important pieces, “Blood Count” starts in d minor and vacillates between this key and D major. Written as he was dying from cancer, the somber mood of d minor juxtaposes with D major. This harmonic process along with a chromatic melody creates a piece painting a picture of eminent death.

Because of the way he used harmony, the key signature is not always that important just as was the case with Evans. Several pieces including, “A Flower Is a Lovesome Thing,” Chelsea Bridge,” “Lush Life,” and “Passion Flower,” and “Blood Count” are known for their tonal ambiguity as they begin. It is difficult to determine where the pieces are headed tonally and tonality is often not established until the end of the first A section as with “A Flower Is a Lovesome Thing” and “Daydream.”

What is sometimes referred to as whole-tone harmony was often used to accomplish this tonal ambiguity. This ambiguity comes from the French Impressionist composers, particularly Debussy and Ravel, whom Strayhorn admired. For example, the melody and harmonic movement of the first three bars of “Chelsea Bridge” echoes the second movement of Ravel’s Valse Nobles et Sentimentales (1911). Strayhorn disputed that there was any direct influence saying that he had never heard the piece. Nevertheless, the harmony in the first four measures typifies the non-functional harmony of Debussy.

Chromatic harmony and tritone substitutions are typical Strayhorn elements. A good example of their use occurs in “Passion Flower.” The harmony of the A and B sections are as follows:

A: | F#9b5 | F9b5 | F#9b5 | F9b5 | E7#5(b9) Eb7 | D7 D7b9 | G69| B: |Dbmaj7 | C9#11 | B9#11 | Bb7#5(b9) | A9#5 | Ab7b9 | Dbmaj7 |

This is anything but a traditional harmonic progression.

Another example is the B section of “After All:”

| Fmaj7 | E7 | Eb6 | Am7 D7 | Db6 | C7 | B13 Ab13 | G13 | Virtually all of the pieces analyzed contain examples of chromatic harmony.

Some of the more interesting harmonic progressions occur in the bridges. Strayhorn will go to a remote key or simply use the bridge as a modulating device back to the original tonality. Both of these elements occur in “Chelsea Bridge” where the tonality changes from Db to E major immediately. At the same time this bridge is a modulation from E major to Db major. The B section for “After All” is similarly a modulation from F major back to C the original tonic. The B section of “Day Dream” is a melodic sequential modulation from Bb major to F major using chromatic harmony and ii V I progressions. The primary tonal center for “Raincheck” is Eb major, but the B section is in G major. The G tonality with its F# only lasts for four bars, but it is enough to make listeners wonder where Strayhorn is taking them.

Altered chords used to produce a certain color are contained in every piece to some extent. As previously noted the alterations are part of the melody. Because Strayhorn was thinking of arrangements and not just the melody, these alterations are particularly important in achieving the sound color that he sought to achieve. Jazz musicians are known to enjoy substituting chords for the originals ones. Just as was the case with Bill Evans, Strayhorn’s compositions are so complete that substituting chords takes away from the pieces rather than having the potential to add color to them.

It would be possible to write a complete thesis on how Strayhorn used harmony in his compositions and arrangements. The concepts discussed above, however, are the main ones that he employed. Harmonically Strayhorn was much more advanced than his compatriots and the

harmony he used is very much a part of what is termed the Strayhorn sound. His harmony is a key element that makes his music interesting to many people.

The Music of Bill Murray

Do some of the musical specific elements found in analyzing compositions of Bill Evans and Billy Strayhorn appear in the compositions of Bill Murray? There are two ways to approach this question. First of all, there is the aesthetic or higher level viewpoint and second, there is the detailed approach that requires looking at pieces to identify specific elements. In my case, the first approach is paramount.

Since most of my knowledge about the compositions of Evans and Strayhorn comes from listening to their works rather than studying them, I was attracted to a certain sound that resonated with me. Another interesting connection is that I enjoy very much the music of the French Impressionist, particularly Debussy and Ravel. Both of these classical composers were also significant influences on Evans and Strayhorn. Are there specific things that I do that are similar to things that these great composers did?

Many different musical elements are found in the work of Bill Evans and Billy Strayhorn.

For purposes of this comparison, only the following characteristics will be considered: Bill Evans

- Structure/Form

- Lyrical melodies

- Through composed/theme and variations nature of melodies

- Unusual harmonic progressions

Billy Strayhorn

- Structure/Form

- Lyrical melodies

- Chromatic melodies

- Use of repeated rhythmic motifs

- Unusual harmonic progressions

Taking a look at form and structure is a good starting place for this comparison. The following table shows the style for my pieces:

| Style | Compositions |

| Ballad | 3 |

| Bossa Feel | 4 |

| Blues Form | 3 |

| Medium Swing | 6 |

| Up Tempo | 1 |

As is the case with the Evans and Strayhorn tunes analyzed, my compositions tend to fall in the slow to medium tempo categories. While there are three blues form tunes, other than using a blues form these pieces are probably better classified as medium swing. Just like Evans and Strayhorn, I do not consider myself to be oriented toward the traditional blues form or style. The bossa feel for my pieces is an Americanized version of the Brazilian bossa nova. This style did not exist when Strayhorn was composing and it was not a genre that Evans worked with to any extent as a player.

Consequently, it would be unlikely for him to compose a piece in this genre. However, there is an Evans/Strayhorn relationship to the bossa nova in that Antonio Carlos Jobim and Joao Gilberto were well aware of these composers particularly as precursors to cool jazz which was a major influence on the Brazilian composers.

From a key signature perspective, I prefer flat major keys as shown below:

Key Signature Compositions

C major 1

c minor 1

Db major 2

Eb major 4

F major 3

G major 2

Bb major 2

Multiple 1

At first glance I am closer to Strayhorn than Evans. However, with Evans the key signature was not that important as harmonically he went well away from what the key signature showed.

Once again, it is the overall mood/sound of their music that interests me.

Even though logical to Evans, the forms he used were unique and varied all over the place and most of his tunes were through composed or theme and variations. In Strayhorn’s case, he used modified versions of AABA or ABAB most of the time where changes in the melody or harmony were made and most of the tunes are 32 bars long which is not the case with Evans.

My compositions fall somewhere between the two as shown below:

| Form | Compositions | Length Compositions | |

| Blues | 1 | 12 1 | |

| AA’ | 2 | 24 1 | |

| AAB | 1 | 28 1 | |

| ABA | 2 | 32 7 | |

| AABA | 3 | 32+coda 4 | |

| ABAB | 3 | 38 1 | |

| ABAC | 1 | 48 1 | |

| ABCA | 3 | 58 1 | |

| ABCD | 1 |

While they tend to follow the more standard lengths, my forms vary considerably. In this sense, they more closely resemble the through composed nature of Evans’s work, but the melodies tend to be more of a theme and variations concept rather than through composed. As with Strayhorn, my A or B sections are not likely to be exactly the same, as is often the case with many tunes in the Great American Songbook. I am not enamored with A and B sections in the AABA and ABAB forms that are strictly repetitive, and in composing deliberately try to alter the sections in different ways. While it is not possible to determine if this was also the strategy of Evans and Strayhorn, from the pieces studied it would appear that they composed along these same lines.

The B sections of Strayhorn’s tunes often take the listener in a very different direction.

This is also a characteristic of many of my pieces such as “Billy’s Touch,” “Borrowed Thoughts,” “Getting Closer All The Time,” “Making A Difference,” and “Thinking of You.” Significant changes in the melodic concept, harmony, and rhythm occur in these pieces.

At the macro level what I appear to have taken from Evans and Strayhorn is a feel, mood, color concept rather than any specific musical elements. My structure and form come from what I thought the piece required when it was being written. To me it seems very logical but others may have different opinions. I am interested in my pieces appearing to be spontaneous rather than predictable. For example, my compositions require musicians to maintain a high level of concentration, which make my pieces more challenging to memorize. Musicians cannot just memorize the A or B section and think that they are home free. Such was also the case with Evans, and because of the structure and form most of them were not recorded by jazz musicians other than himself.

Both Evans and Strayhorn were known for their lyrical melodies and this is one of the elements that has always attracted me to their music. I have been told by people that have listened to my pieces that they contain interesting and strong melodies. Developing an interesting melody is an important aspect of my compositions. Other than an overall concept, there are not that many specific melodic elements that Evans used that appear in my work, but I want my melodies to sing just as Evans did with his. I am more structured in my approach to melody than his through composed melodies where the melody changes constantly.

On the other hand, several techniques that Strayhorn used appear regularly in my work.

The first is a chromatic melody with two intervals appearing regularly, a minor second and a tritone. Voice leading using these intervals is important to me. Examples of chromatic melodies occurring are “Always Changing,” Billy’s Touch,” “Fun and Games,” “Making A Difference,” “My Love for You,” and “No Strings Attached.”

A second technique is the importance of upper structure chord tones and altered notes in the melody. “Billy’s Touch,” “Making A Difference,” “While Dancing,” and “Your Special Day” are examples of this. It is not uncommon for me to end a phrase or section on one of these notes to signify that something more is to come. Nor do phrases or even the end of pieces need to resolve in the traditional sense.

A third technique often used by Strayhorn was basing a piece on a specific rhythmic pattern. “Billy’s Touch,” “Getting Closer All The Time,” “Making A Difference,” “Moving On,” “Stepping Down,” “What’s Up,” “While Dancing,” and “Your Special Day” are all based on one or two specific rhythmic patterns. For example the following pattern with different pitches is used to start every phrases in the A sections of “What’s Up”.

“Getting Closer All The Time” is based on two patterns again with different pitches.

Finally, a fourth technique that Strayhorn used was a rhythmic pattern to unify pieces. “Borrowed Thoughts,” “Fun and Games,” and “Remembering” all employ this process. Again Strayhorn’s work was not analyzed prior to using these techniques in my compositions, but they appear far more frequently in my work than I realized.

More than anything, the harmony of Evans and Strayhorn attracts me to their music.

Their harmony creates a sound that I sought to reproduce. It is what my ear heard that became important to me rather than any theoretical approach to harmony. Both Evans and Strayhorn seem to take much the same approach. While both were well versed in traditional harmony, they were not concerned about going outside this approach if it produced the sound that they were looking to achieve with a particular piece. This has been my approach particularly in my early compositions.

Delayed resolution is common in many of my compositions as was the case in both Evans’s and Strayhorn’s works. Pieces do not resolve traditionally until the end of the tune and they may end on other than the tonic. Short codas are sometimes added to allow for greater harmonic resolution.

Unusual harmonic progressions are common to their work and mine as well. The chords for the first eight bars of “Always Changing” are:

| Cmaj7 Ebdim7 | Dmin7 D#dim7 | Emin7 C7b9 | Fmaj7 |

| Fmin7 E7 | Ebmaj7 | Ebmin7 D7 | Dbmaj7 |

Strayhorn also used this chromatic harmony frequently. The first twelve bars of “Two and Four” have the following harmony:

| Dmaj7 | Emin11 | F#min7 | Gmaj7 |

| F#m7 | Emin7b5 | Fmaj7#5 | Emin7 |

|F#min7 | Gm9 | A13 | Dmaj9| Once again a very unusual harmonic pattern was used.

While my music abounds with the traditional ii V I of jazz, there are many instances of going where my ear takes me rather than paying attention to theoretical harmony. For example in bars 4-8 of “Billy’s Touch,” the harmony is:

| Ebmaj7 Ab13 | Fmin7 G7#5 | Cm7 Bbmin13 | Abmaj7 |

While the root motion may be considered somewhat normal, the chord quality is not. “Borrowed Thoughts” is another example of the importance of different progressions and chord qualities.

The first chords of the B sections are:

| Ebmaj7 C7b9 | Fmin7 Bb7 | Abmaj7/E7 | Ebmaj7 Emin7 |

| Bmin7 | E7 | Cmin7 | Fmin7 E7#11 | Abmaj7 |

This progression gives the piece the desired sound even though it is outside the traditional rules of music theory. Chord quality is an important part of my compositions because the designated chord quality provides a particular color that I am looking for. This was important for both Evans and Strayhorn and the reason that their harmonies often went in unusual directions. It is often said that their tunes were so complete that no chord substitutions should be made because changing the chords would result in undesirable changes to the mood of the piece. Evans and Strayhorn have both had an influence on my harmonic approach even though it was not realized when the pieces were being written.

Appendix I: Bill Evans, Billy Strayhorn, Bill Murray Compositions Analyzed for Musical Elements

| Bill Evans Compositions | Billy Strayhorn Compositions | Bill Murray Compositions |

| Bill’s Hit Tune | A Flower Is a Lovesome Thing | Always Changing |

| Epilogue | After All | Billy’s Touch |

| Funkallero | Blood Count | Borrowed Thoughts |

| Interplay | Chelsea Bridge | Explorations |

| Laurie (The Dream) | Clementine | Fun and Games |

| Only Child | Day Dream | Getting Closer All the Time |

| Orbit (Unless It’s You) | Isfahan | Making A Difference |

| Peri’s Scope | Johnny Come Lately | Moving On |

| Re: Person I Knew | Just A Settin’ and A Rockin’ | My Love For You |

| Show-Type Tune | Lotus Blosson | No Strings Attached |

| Since We Met | Lush Life | Remembering |

| Story Line | Midriff | Stepping Down |

| Song For Helen | My Little Brown Book | Thinking of You |

| 34 Skidoo | Passion Flower | Two and Four |

| Time Remembered | Rain Check | What’s Up |

| Turn Out The Stars | Something To Live For | While Dancing |

| The Two Lonely People | Take the A Train | Your Special Day |

| Very Early | Upper Manhattan Medical Group | |

| Walkin’ Up | ||

| Waltz For Debby |

Appendix 2: Summary of Composition Analysis for Selected Bill Evans, Billy Strayhorn and Bill Murray Compositions

Bill Evans Composition Summary Analysis

Billy Strayhorn Compositions Summary Analysis

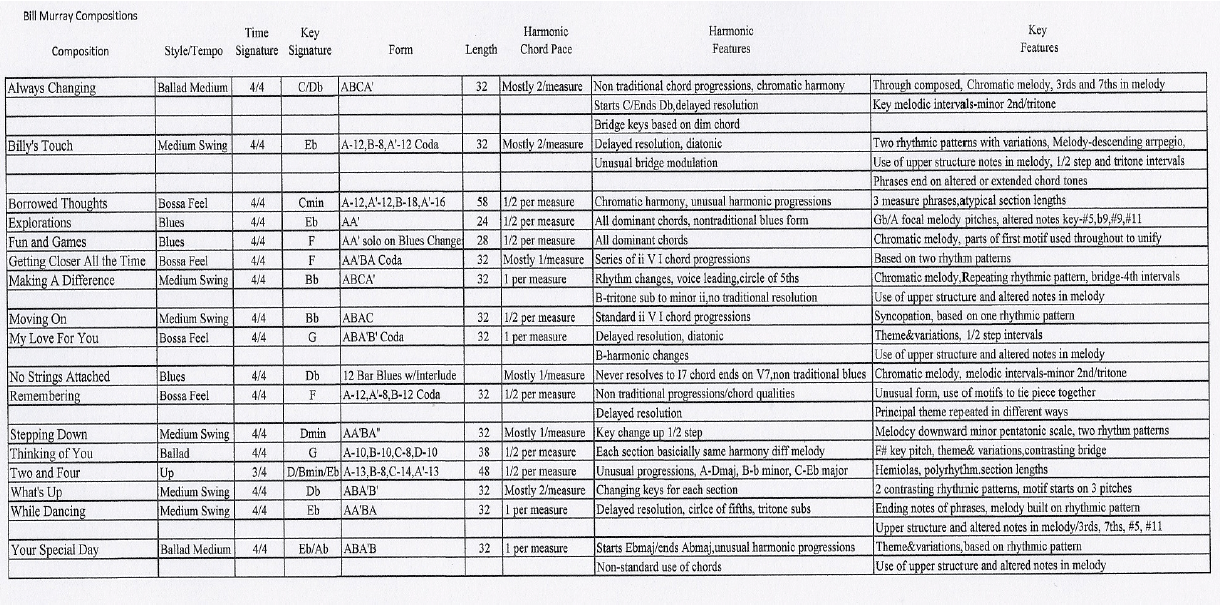

Bill Murray Composition Summary Analysis