Table of Contents:

Browse in the Library:

SWANEE RIVER BOOGIE WOOGIE – ALBERT AMMONS (sheet music)

Boogie Woogie

The Boogie Woogie is a piano-based style of blues, generally fast and danceable. It is characterized by the execution with the left hand of certain figures.

These figures that the left-hand builds are written in eighth notes, in 4/4 time signatures, thus constituting the so-called eight-to-the-bar.

Two types of figures were usually used: the so-called ‘galloping eighth’ (inspiring the ‘galloping basses’ or walking bass that would later characterize rock and roll), as well as the fast chords known as rocks.

History of the Boogie Woogie

Unlike ragtime, boogie-woogie was never influenced by the European piano repertoire. The musicians who began to forge it in the American South, around the late 19th and early 20th centuries, had probably never heard a classically trained pianist.

Its origin is not precisely known, but it is assumed that it took place in the Mississippi Delta area or in Texas, in the bars known as barrel houses (the name by which the new style was also known) where the pianists who Usually they were limited to accompanying the singers, they developed a fast and purely instrumental way of the blues with the aim of making it danceable.

The percussive powers of the piano had never been so exploited in pop music until these anonymous boogie-woogie inventors managed to impose their music in the midst of the bustle of the clubs and create hypnotic effects through their fast rhythms, repetitive melodies in counterpoint with also repetitive basses and a harmony that was never separated from the original tonality.

The basic functionality of the style and its simplicity earned him the scorn of the finest jazz musicians, such as Jelly Roll Morton, who is said to have resented being asked to perform a boogie-woogie.

Best Sheet Music download from our Library.

Among the first to witness his birth are W.C. Handy, the aforementioned Jelly Roll Morton and Clarence Williams, who had already heard piano playing in this style in the tens or even earlier. Williams also adds the name of the first performer for him, George W. Thomas, whom he had heard playing in Houston in 1911.

Indeed, Thomas’ compositions already contain elements of boogie-woogie: ‘New Orleans Hop Scop Blues’ (composed and published in 1916), ‘The Five’s’ (recorded in 1923 by the Tampa Blue Jazz Band) and ‘The Rocks’ (recorded by the author himself in 1923) are among the first pieces to contain galloping eighths.

During the years between the two world wars, with the intensification of the migration of people of color from the South to the cities of the North in search of less racial prejudice and better jobs, three cities had the privilege of hosting the largest number of pianists (and musicians in general), enough for the main schools of boogie-woogie to settle in them. Thus, Chicago, first, and then Kansas City and St. Louis, concentrated a good part of these pianists from the South in their bars and recording studios.

The aforementioned George W. Thomas arrived in Chicago from Texas. In February 1923, under the pseudonym Clay Custer, he recorded his song ‘The Rocks’, a hybrid of ragtime and boogie-woogie considered the oldest phonographic record of a galloping octave. From Alabama, for his part, came Jimmy Blythe, who recorded his ‘Chicago Stomp’ in April 1924, a piece before which we can already say that we are facing a true boogie-woogie.

However, since 1915, Jimmy Yancey, a native of the city but without the opportunity to record until the late thirties, had become one of the most popular entertainers of the so-called house-parties (parties organized by blacks from the ghettos in their own houses in order to raise funds to pay the rent). One of his earliest compositions, ‘The Fives’ (not recorded until 1939), had helped lay the foundation for the style.

On the other sidet, Cow Cow Davenport, a native of Alabama and who became known as ‘the man who introduced boogie-woogie to America’ (according to his business cards), records on July 16, 1928, in Chicago , one of the classics of the style, his ‘Cow Cow Blues’, a musical imitation of the rolling of the railways (hence the title of the piece and the nickname of its author), a theme that since then was foreshadowed among those preferred by boogie-woogie performers.

Over time, it will be said that the sound of the trains in which the itinerant or migratory musicians traveled was the inspiration for the boogie-woogie rhythm.

Of all the first generation of pianists who worked in Chicago, the most recognized is undoubtedly Pinetop Smith, a disciple of Yancey who had come to the city, like Davenport, from Alabama. Pinetop has the merit of having composed towards the beginning of the twenties, and subsequently recorded on December 29, 1928, the most covered song in the history of boogie-woogie and the one that would give the style its name, ‘Pinetop’s Boogie Woogie’.

About the combination of the words boogie and ‘woogie, Smith would say that it meant nothing; he had simply heard them together once during a party.

In the recording, while playing the piano, Smith dictates the instructions for dancing to this type of music (…when I say stop, don’t move, and when I say get it, everybody mess around…), and uses the term (the boogie-woogie) without distinction between others traditionally associated with popular dance (to mess around, to shake). These phrases uttered over the music became a widely followed tradition among boogie-woogie pianists.

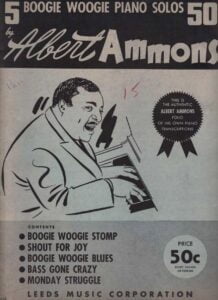

Pinetop Smith represented in Chicago the link between his generation and the next. In this city, where he arrived in 1928, he settled with the young local pianists Meade Lux Lewis and Albert Ammons in the apartment that the latter occupied on the South Side.

Please, subscribe to our Library. Thank you!

Albert Ammons was the only one who had a piano of his own, and in his room the three pianists met to play. They were months of fruitful exchange that were interrupted when, in March 1929, Smith was assassinated by a stray bullet in a ballroom in the city. The event marked the end of a stage in the history of boogie-woogie, and half a decade would pass before it managed to make its way again on the music scene.

Fortunately, shortly before he died, Smith had taught Ammons to play his ‘Pinetop’s Boogie-Woogie’. In the end, the two young disciples of Smith would become the greatest interpreters of the Chicago school, as well as champions of the renaissance that the style experienced in the second half of the 1930s.

Meade Lux Lewis, in fact, had started her adventures a little earlier, but misfortune marked (and she would continue to do so for a while longer) his career.

In 1927, he had recorded his future classic ‘Honky Tonk Train Blues’, but the record could not be released until eighteen months later, in 1929, without any commercial repercussions; the closure of Paramount Records, shortly after, ended up putting the recording off the market.

These were the times of the Great Depression, which very few pianists of the first generation managed to overcome, and even the youngest, such as Lewis and his partner Albert Ammons, had to dedicate themselves to activities far from music, a need that, however, could not bury the natural inclinations of both.

It is said that during the time they shared working in a taxi company, they used to leave the company headquarters to go play the piano; when the owner of the company discovered the reason for his absences, he bought a piano and placed it in the office to have the two taxi drivers available whenever he needed their services.

For luck to begin to favor him, Meade Lux Lewis had to wait until John Hammond, visionary producer and promoter of jazz, blues and folk, discovered the recording of ‘Honky Tonk Train Blues’ and began a search for his interpreter that would take several years and during which he would also run into Albert Ammons. This is how Hammond narrated his tracking of the pianist:

When I heard the recording of ‘Honky Tonk Train Blues’ in 1931 I knew I had found the ultimate [boogie-woogie] player in Meade Lux Lewis. But no matter where I looked or who I asked, I couldn’t find it. Years later, in Chicago, I asked for him again while having lunch with Albert Ammons. ‘Meade Lux?’ Albert said, ‘of course, she’s washing cars on the corner.’ And indeed, there he was.

This happened in November 1935, and before the end of the year, Lewis had already restarted his recording career with the recording of a matured version of ‘Honky Tonk Train Blues’.

The most famous example of the railway theme and the bass variety called rocks in the entire boogie-woogie repertoire, the piece was inspired by a train passing very close to one of the houses where Lewis had lived, in the Chicago’s South La Salle Street, making her shudder several times a day; its title was the idea of a guest at one of the many house-parties that the pianist hosted.

For his part, at the beginning of 1936, Albert Ammons recorded, accompanied by his group, the Rhythm Kings, an energetic version of the Pinetop Smith theme, which he called ‘Boogie-Woogie Stomp’.

Albert Ammons added more speed and rhythmic strength to the style by bringing it closer to the small jazz line-up (few had tried it before: Will Ezell, a then-forgotten pianist in the 1920s, and Cleo Brown barely a year before), with the particularity in this case of the great preponderance of the rhythm section (piano, guitar, double bass and drums) worthy of the great jazz orchestras.

Around the same time, John Hammond also discovered a duo on the Kansas City scene made up of pianist Pete Johnson and singer Big Joe Turner, who from the Sunset Cristal Palace, one of the many taverns in the city (known then as the ‘sin capital’) which, thanks to the permissiveness of Tom Pendergast’s controversial government, offered facilities to obtain alcoholic beverages and marijuana during the prohibition era, began to develop a hybrid of boogie-woogie and vocal blues.

Singing a boogie woogie was not really something new (in the early thirties it was already done by Speckled Red and Little Brother Montgomery), but they were the first to base their particular style on this modality.

Turner, who had always pursued (in his own words) ‘the vertigo and sensuality of the scene in suburban clubs’, from the age of fourteen drew mustaches on his face trying to outwit the guards of these places, and soon managed to not only enter, but perform in them as a bartender, doorman or singer.

He was working at the Sunset Cristal Palace as a bartender that one night, when Johnson was performing there, he joined him singing from the bar in an impromptu performance. His charismatic figure and his powerful voice, in the tradition of the shouters (practitioners of a vocal technique characteristic of the blues, prior to the invention of the microphone, which gave great volume to the singing) They convinced Johnson to start working together from then on.

The impact produced by the duo’s energy and the boogie-woogie vocal variety they practiced made the Sunset Cristal Palace a favorite venue in the city, even for local musicians, who every night after their own performances They went there to listen to them.

By December 1938, the tireless John Hammond organized a great concert at Carnegie Hall in New York with which he wanted to show white audiences the evolution of American black music, its main trends and its relationship with African music. A project of such magnitude and that at the same time implied so much commercial risk did not find any sponsor other than the weekly New Masses, the organ of cultural diffusion of the communist party for which Hammond used to write.

The success of the event was to represent a major step forward in the battle for racial integration, and Hammond would thereby demonstrate his belief that black music was the ‘most effective and constructive form of social protest’. Thanks to this concert, both Lewis and Ammons as well as Johnson and Turner had the opportunity to show their art before the crowd that filled the most important theater in New York, and to share the bill with figures such as Count Basie, Sydney Bechet, James P. Johnson and Big Bill Broonzy, among others.

The songs that the four musicians interpreted, especially those of the piano trio of Lewis, Ammons and Johnson (which became known as the Boogie-Woogie Trio) as well as those of the latter and Turner duet, drew the loudest applause from all over the world and spurred the boogie woogie craze across the country.

The style was no longer, as William Russell had said at the time, ‘the most anti-commercial music in the world, in the best and worst senses’, and far surpassed its brightest days before the Great Depression. .

For Lewis, Ammons, Johnson and Turner the commitments began to happen from the days that followed the concert. Between the last week of 1938 and the first week of 1939, Hammond arranged for them several recording sessions with various New York record labels, which resulted in many of the most celebrated records of the golden age of boogie-woogie.

It was in these two weeks that the variety of vocal boogie-woogie that Johnson and Turner had performed since their days at Kansas City’s Sunset Cristal Palace was recorded in studio for the first time. ‘Roll’ em Pete’, the song selected for the occasion, owed its name to the shout with which the audience of the aforementioned venue encouraged the pianist during his presentations.

It is worth wondering why the hybridization of vocal blues and boogie-woogie had not achieved such a perfect assembly before, despite having had several precedents; but by defining itself from its beginnings as an instrumental form of great rhythmic and sound power, boogie-woogie would leave behind the chance of being accompanied by the human voice until a singer capable of taking the style of the old shouters as far as possible appeared. , and this singer finally appeared in the figure of Big Joe Turner.

Also, after the concert and again thanks to Hammond, the Cafe Society Downtown hosted Lewis, Ammons, Johnson and Turner, who were beginning to be known as the Boogie-Woogie Boys, for about two years. This newly opened club located in New York’s Greenwich Village was beginning to experience, like boogie woogie, a great moment. Its owner, the lawyer and merchant Barney Josephson, a member of the communist party and a friend of Hammond, had founded it with the purpose of raising funds for this political organization.

It was the first club that had a racially integrated audience in its spaces. The public that used to visit the place had the opportunity to see in it, surrounded by murals designed by Adolf Dehn, James Hoff and other painters of the time, artists of the stature of Billie Holiday and James P. Johnson, among others, as well as like attending the best days of boogie-woogie.

It is there where it is supposed that the short film Boogie-Woogie Dream, directed by Hans Burger, was filmed in mid-1941 and could not be edited until 1944; in it appear Ammons and Johnson interpreting the theme that gave the film its title.

The boogie-woogie craze dominated the American black music scene (which was gaining more and more ground among white listeners) with great force until 1942, and then, to a lesser extent, until the middle of that decade. During those years it invaded practically every club, every radio station and every jukebox in the country.

It penetrated the repertoire of other instruments (for the guitar, Blind Blake had set a precedent a decade ago) and even into that of other styles such as country, avant-garde academic music (remember Conlon Nancarrow’s compositions for piano) and, above all, everything, jazz It eventually laid the foundation for jump blues and much of rhythm and blues and rock and roll.

Two recordings by Albert Ammons give an account of the advances of boogie-woogie in the final years of his reign. The first of them, ‘The Boogie Rocks’ (1944) is one of the most powerful pieces recorded by this pianist; its eloquent title seems to echo the evolution that the style was undergoing and that would not be verified until some ten years later, but our ears already recognize in it the sound that would later characterize pianists such as Jerry Lee Lewis and Little Richard, the most faithful heirs of this tradition in the field of rock and roll.

The second, ‘Doin’ the Boogie-Woogie’ (1946) synthesizes, in one song, that idea of orchestral boogie-woogie that Ammons himself had begun to investigate ten years earlier with that other of vocal boogie-woogie that they had His friends Johnson and Turner worked as well a decade ago.

Instrumentally, the guitar has gained ground and when it comes to solo, it half shares the role with the piano. In essence, we are already facing one of the many styles that over time will be labeled as rhythm and blues.