Table of Contents:

András Schiff breaks the silence:

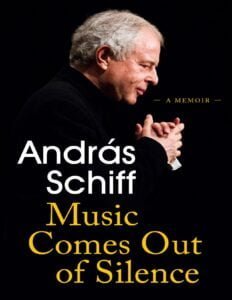

Music Comes Out of Silence (Book)

The presumption that music is self-sufficient seems, at first glance, to be typical of someone who does not make music. The latter wants to know everything, although he conversely needs the superstition that there is nothing to know because there is only a sound air.

It is true that the composers themselves also placed their merchandise, such as the anecdote of the one who, when asked about the meaning of a piece, limited himself to playing it again. The facts prove, however, that there is much to say, literally. The facts here are the amount of writings left by composers and performers.

Among them, the autobiographical ones are the majority (the memoirs of Berlioz, Arthur Rubinstein, Wilhelm Kempff and so much more).

Please, subscribe to our Library. Thank you!

There is, on the other hand, a singular species, more typical of the pianist, between evocation and analysis. We have Edwin Fischer, Alfred Brendel and, now, András Schiff, probably the greatest active pianist alive. Musik kommt aus der Stille (there is an English version: Music Comes Out Of Silence, and also in French) is presented as a ‘memory’ of Schiff, but we must not be fooled, unless we conclude that the only memory of him is musical.

The first part of the book is a conversation with the Swiss journalist Martin Meyer; the second, a more or less occasional gathering of essays and writings (on György Kurtág, Beethoven’s String Quartet opus 132, the evocation of Annie Fischer). However, whether you talk about his very strict habits or the color in Bach’s keyboard music, you reach the point where you don’t know if you need to talk or not, and what you are talking about when you do.

Schiff says: “Music has to do essentially with the spirit and with the spiritual”. The sentence is not weakened by any vagueness, and the pianist himself explains it with an example that would not have displeased Hegel: “What is the difference between the cathedral of Florence and a swallow’s nest? The deliberate intention to create a work of the spirit. Therein also lies the difference between the song of a nightingale and Bach’s The Art of Fugue”.

Schiff is aware that all this is now outdated; nor that the musicians of his time (Sviatoslav Richter, Claudio Arrau) were far superior to the current ones. Why were they? Because they knew what is no longer known now. And what is there to know?

For example, that a Schubert sonata is more fragile than one by Beethoven, that the Schubertian form is more lax, that it therefore runs the risk of disintegrating if one does not know where to contain it, and that it is rhythm that is the backbone.

It could be suspected that any pianist would realize this, but this is not what happens and it is enough to listen to the Schubert played by Lang Lang to confirm it. We did not have the fortune of Schiff, but our gain is to be his contemporaries.

Other things are less obvious to check. The courage of a musician goes unnoticed by someone who is not a musician or knows nothing about music, because in addition to civil courage (Schiff’s decision not to perform in Austria after the electoral success of Jörg Haider, for example), there is another courage that it is not even heard and hopefully seen (rare thing that a musical courage is subordinated to being seen). Schiff explains it with his admiration for Rudolf Serkin, who never looked for easy solutions.

At the beginning of the Hammerklavier sonata, and also at the beginning of the sonata opus 111, Beethoven asks for a daring jump with the left hand, which could well be more safely solved with both hands (the right is idle). It was not so for Serkin that he opted for the danger of error. Says Schiff: ‘This is the real morality of a musical act.’ Arrau thought the same about those two passages, and he also drew the conclusion that, at least for Beethoven and perhaps always, the difficulty was part of the expression.

If it were true that the only thing that can be explained about music is its inexplicable condition, then it would be written to explain that it cannot be written, to explain that it cannot be explained, to show that it is inexplicable. Those words wall off the inexplicable, protect it, elucidate it.

Best Sheet Music download from our Library.

About this book

All music is interpretation. Each musical text offers its readers guidance and direction on how to bring that music into existence. But behind every command or notation lies the imagination, and it is this that brings the music out of its silence, out of mere possibility, into performance in the here

and now.

Few musicians have thought about this process, as music moves from idea to reality, as intensely and precisely as András Schiff. Pianist, conductor, scientist and commentator, he is the product of numerous qualities and experiences. And in the end, music is about the performance,

expressed as a statement that can be understood in the present day – and beyond. Schiff did not become a virtuoso in order to further his own ends.

Even in his youth, he had a deep awareness of the responsibilities for one’s own actions. Indeed, he views music as a combination of not only work and research but also spirituality and conscience, and all this is expressed through the masters, from Bach to Haydn, Mozart to Beethoven, Schubert and Schumann to Brahms.

Schiff’s ability to combine intellectual tension with the sensual qualities of playing is singular.

In other words, when we hear Schiff perform, we cannot help but recognize that a truly attentive musical mind must not only read the music, but consider it, guide it, even argue with it in order to produce truly great sound. For nothing would be gained if the many insights, research, knowledge and reflections involved did not lead to sound.

This book is all-encompassing, in the same sense as a tour d’horizon, addressing the essential points of biography, while exploring the secrets and adventures of music with a view to its design. Schiff proves to be a generous partner in conversation, discussing a multitude of topics with verve and passion, as well as his well-known – and often self-deprecating – sense of humor.

Above all else, one thing is clear: the vocation of a musician does not come about by itself or because of some latent ability or talent. It requires patience and a great deal of hard work.

No example is more illustrative of this than the fact that Schiff did not dive into the cosmos of Beethoven’s sonatas as a talented young man, but instead, did so only relatively recently, having invested a lifetime of preparatory work.

This book is composed of two parts. The second part contains a rich series of essays, analyses and portraits. Schiff writes about his favorite works and composers in a precise and inspired way, and many of them will be familiar to you. This doesn’t make an essayist’s job any easier!

On the contrary, the whole world seems to know what Bach, Schubert, Mozart or Mendelssohn should sound like. Sometimes it seems as if we’ve heard it all – until we listen to Schiff, who brings something newer, more exciting,

more profound, and clearer to the table.

These writings stand as testaments to Schiff’s talent for the written word.

The first part shows conversations that András Schiff and I had at regular intervals over the course of two years. These conversations always seemed to me to be like music, just waiting to be launched from silence.

Martin Meyer

Zurich, January 2020