Table of Contents:

Sun Ra (born Herman Poole Blount, May 22, 1914 – May 30, 1993)

Herman Poole “Sonny” Blount from Birmingham, Alabama, became Le Sony’r Ra, from Saturn. In adopting a new name and birthplace and erasing ties to his past, Ra provided an example for others who yearned to shed their given names—a constant reminder of slavery and oppression.

Sun Ra’s name went through several transformations, with which he sought to distance himself from his given name.

Please, subscribe to our Library. Thank you!

Sun Ra’s biographer, John F. Szwed, outlined several name changes and the reasons behind them in his book Space Is the Place, Ra’s names over time included: Sonny Blount, Sonny Bhlount, H. Sonne Bhlount, the last of which he deciphered to mean “the sound of God.”

Several name variations later, Ra approached his friend and band manager, Alton Abraham, about officially changing his name. Abraham was supportive. Ra debated between “La Sun Ra, “Le Sun Ra” and “Le Sony’a Ra,” but ultimately settled on “Le Sony’r Ra.” The reasons for this final change to his name before making it official in 1952 remain a complete mystery and a secret that Ra never revealed.

The last little bit of information regarding his name must—appropriately—remain a secret, to reinforce the symbolic connection that mankind can never know all the secrets of the Cosmos.

Sun Ra Montreux 1976 (II): Take The A Train

(Sun Ra and Arkestra playing Billy Strayhorn’s “Take The A Train” at the Jazzfestival Montreux on July 9th, 1976).

Taking control of his destiny, starting with his own name, meant freedom and the ability to redefine words, breaking away from the confines and negative connotations of language. His deep interest and study of etymology—the re-naming and redefinition of words (with different spellings)— became an important factor for him and other African Americans.

His teachings on religions and philosophy had a profound influence on his band members, and a wide circle of musicians, friends, and supporters.

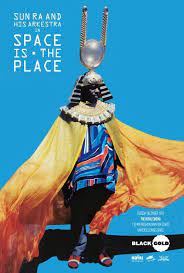

These themes are continuously re-visited in his music and lectures, as well as in the film Space Is the Place. Ra frequently gave lectures, before, during, or after his concerts, in which he weaved a narrative from historical, mythological, philosophical, and etymological perspectives.

The Cold War, Space Race, and the Civil Rights movement of the 1960s and 70s had a profound effect on Ra’s music. As with Cage, and many other artists of the time, these historic events served as inspiration for many musical works of Ra. As an African American, the Civil Rights movement, coinciding with the Cold War and the Space Race, had an additional impact on Ra. Religion, race and identity played a central role in Ra’s career.

However, Ra often found himself in disagreement with different religious groups (such as Nation of Islam followers, Baptists, or other Christians). Not fitting in any “box,” Ra devoted his time to the broad study of religions, etymology, history, science, and science fiction. This led Ra to unique and firmly held beliefs of his own particular views on religion and philosophy.

Ra’s music became deeply rooted in his own “brand” of religion. He often spoke to his audiences about his religious teachings and philosophies, and by the mid-1950s Ra became an “international spokesman for the creator of the Omniverse,” writing, proselytizing and distributing leaflets.9 He carefully studied the Bible and other religious texts, deriving interpretations that did not always fall in line with the doctrines of traditional religions.

Another source of influence for Ra was science and science fiction. Science fiction became very popular in the decades spanning the Cold War and the Space Race, and Ra was an avid fan of science fiction. The Cold War between the United States and the Soviet Union prompted a scientific and military push with the intention to outmaneuver the declared enemy. The control of land, water and air was crucial, but both countries had their sights set on a new frontier: space.

Military leaders on both sides realized that satellites could be used to monitor or deploy weapons from space, without being easily detected. Now civilians also had to fear attacks from land, water and air, as well as from missiles launched from space.

The media picked up on this scenario by releasing films, graphic novels, books, etc., all with the intent to answer one question: what is waiting for mankind out in space? How will these scientific advances (mainly robots) change life here on earth? Many artists added their own commentary to the Space Race movement.

It was in this frenzy that Cage picked up a newly-published star atlas, which he used to write Atlas Eclipticalis. But unlike Cage, Ra and other African Americans did not have equal opportunities to pursue government sponsored space-related occupations, or to even be part of the main-stream media conversation on this topic. Arguably the greatest feat achieved by humankind—the moon landing—was to be done by an entirely white, male crew.

Being left out of the scientific endeavors, Sun Ra and others in the black community turned to music as a viable tool to build a space-exploration narrative. Without access to space exploration technology, music became a means to “transport black people to other states of being in both material and spiritual terms.”

Highlighting the unrest, inequality and lack of opportunity, Gil Scott-Haron released “Whitey on the Moon,” a poem set to music on his new album A New Black Poet – Small Talk at 125th and Lenox (1970).

A rat done bit my sister Nell.

(with Whitey on the moon)

Her face and arms began to swell.

(and Whitey’s on the moon)

I can’t pay no doctor bill.

(but Whitey’s on the moon)

Ten years from now I’ll be paying still. (while Whitey’s on the moon)

The man just upped my rent last night. (‘cause Whitey’s on the moon)

No hot water, no toilets, no lights.

(but Whitey’s on the moon)

I wonder why he’s upping me?

(‘cause Whitey’s on the moon?)

The lyrics paint a picture of the standard of living for millions of African Americans, in direct contrast to whites landing on the moon. It highlights the injustice of affording luxuries of space travel while an entire race was subjected to deplorable living conditions. How could these two extremes of such inconceivable human achievement coupled with sub-human treatment and living conditions exist within the same community?

Although the development of Afrofuturism cannot be attributed to a single person, the term itself has frequently been ascribed to Mark Dery who describes it as:

Speculative fiction that treats African-American these and addresses African-American concerns in the context of twentieth-century technoculture—and, more generally, African-American signification that appropriates images of technology and prosthetically enhanced future—might for want of a better term be called ‘Afro-futurism.

Afrofuturistic” is a term frequently used to describe Ra’s music. Furthermore, Ra and his Arkestra members regularly played their concerts in costumes and clothing that were in line with Afrofuturism.

There is no doubt that Ra was a key figure in spreading awareness on this topic.

Various religions played a part in Ra’s music. Christianity, Islam, Egyptian, African or other ancient myths, are intertwined with his music. Ra’s study of religion was incredibly systematic. Although the entirety of his study cannot be discussed in the scope of this chapter, a sole example of one of his street-corner sermons will illustrate the point. To begin the discussion of his obsessive study of religious texts, etymology must be discussed first. John Corbett described Ra as a “logophile,” a lover of words and homophony, where the “words [are] another form of music.”

As mentioned before, etymology—the study of the origins and history of words, was a passion of Ra’s and played a significant role in his music and teachings.

In many of his street-corner sermons, Ra used etymology to explain, deepen, or even re-interpret the meaning of a word. In one sermon, he begins with the study of the word “Christianity” and delves into historical, mythological, cultural, and religious meanings tied to the word. A section of a street-corner sermon outlining some of Ra’s views on Christianity and his obsession with etymology and words also shows his philosophical tendencies as well as his fascination with early Christian history:

“Christianity is a religion based upon the [word] of Christ, but when used in this manner it should be spelled Christionity. There is a difference between the people who believe in Christ and the people who believe on Christ. The meaning of this will require study by those who are interested. The word chrest is also significant, and we should not neglect the word crest because a crest is a shield or a coat of arms. Crest also means top. It is remarkable that people are in ignorance concerning these two words. We recommend that you research upon the words chrest and chrestion.”

Ultimately, Ra saw much of Christianity as false and oppressive. Ra explored these ideas further in the film Space is the Place, whose plot—although set in modern times— closely follows ideas of the Bible.

Ra’s ultimate goal was to “awaken” the people to his teachings and to allow the Rapture to happen; this is depicted at the end of the film when Ra takes a few African Americans aboard his spaceship and takes them to a new planet, while the rest are left behind on a “fallen” earth controlled by the Devil. This event can also be viewed as an Exodus (like in the Old Testament) when Moses led his people out of the oppressed land of Egypt where they served as slaves, into the new land, where they were free to start anew.

Ra and his Arkestra gained international fame in the 1950s as they toured across America, Europe, and Asia not only for their futuristic space-inspired jazz, but also for the costumes, headgear, and other visual aspects that accompanied Ra’s performances.

Since the 1950s, Ra’s band, The Intergalactic Myth-Science Solar Arkestra, was commonly referred to as “the Arkestra.” Acknowledging a rare reference to his birthplace, Ra named his band Arkestra, joking that this is how “orchestra” is pronounced in his native Alabama.

It was also fitting that the spelling of the word references the Biblical Ark.21 The symbolism of the Ark is a reoccurring theme in Ra’s work: it is a vessel, a ship, and a tool, sometimes physical, sometimes metaphorical, by which Ra transports himself and others to and from Earth, across the Solar system, into the past, and into the future.

His band, the Arkestra, signifies a metaphorical ark that carries the music, ideas and the seeds of his philosophical and religious teachings as the group travels around the world. At other times, the Ark is the music itself, transporting Ra’s audience into the future through experimental, futuristic jazz; at other times still, the Ark is the spaceship in Space is the Place, which carries Ra and his passengers across the Solar System.

Ra’s views and philosophies caused many to question Ra’s authenticity, sincerity, and commitment to his principles and his identity. However, this only seemed to strengthen Ra’s resolve: “I believe that if one wants to act on the destiny of the world, it’s necessary to treat it like a myth.”

Ra held a life-long insistence on the necessity of myth, not only in history, music, and art, but also in every aspect of life. The subject of myth, myth-science, mythocracy, and mythology, which captures the vision behind Ra’s passionate pursuit of the subject.

He insisted on the necessity of myth, not only in history, music, and art, but also in every aspect of life. In his eyes, to change the world, it is necessary to examine the boundaries of reality, truth, and mystery.

There is a deeper truth to Ra’s philosophies and teachings: as he invites his listeners to examine these boundaries, they discover that there may not be any boundaries at all. In fact, they may be seen as myths themselves. In his eyes, to change the world, it is necessary to examine the boundaries of reality, truth, and mystery. June Tyson, singer in the Arkestra, proclaimed: “If you are not a myth, whose reality are you? If you are not a reality, whose myth are you?”