Table of Contents:

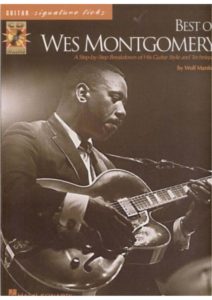

WES MONTGOMERY (1923-1968)

Of the handful of players who defined the art and characteristics of modern jazz guitar, three names continually recur: Django Reinhardt, Charlie Christian and Wes Montgomery.

While it would be overly simplistic to suggest that these players alone shaped the course and destiny of the guitar in jazz, they have been, and continue to be, the overriding, pervasive, influences of the genre.

Regardless of the fickle trends and fashions, which are so much an integral part of popular music in the late 20th century, Montgomery’s popularity shows no sing of diminution.

Best Sheet Music download from our Library.

His recordings are universally revered and remain constantly in the catalog. Highly regarded by musicians and listeners alike, Montgomery’s music continues to reach new audiences. Its subtle blend of sophistication, and simplistic inevitability, captivates, motivates and inspires each new generation of guitar players. As with all great jazz players, his music is time-less, transcending vogue and anachronism with a vibrancy which remains as relevant today as when it w as first conceived.

Many critics, and jazz historians, would have us believe that Montgomery was such a huge natural talent that it took little effort for him to develop into the musical giant he eventually became. While no one would deny his obvious and precociously apparent musical gifts, his fully-fledged mature style was not formed without recourse to the usual rounds of dues-paying, disappointment and sheer hard work.

Neither did he begin playing the guitar at the age of 19 and by the following week was hired by a passing club-owner, on the strength of being able to replicate all of Charlie Christian’s recorded solos! Nothing could be further from the truth.

Please, subscribe to our Library. Thank you!

Monk, Wes’s elder brother, who was a proficient bass player by his late teens, gave an 11-year-old Wes a four string “tenor” guitar to fool around with. Monk later recalled that he was actually playing very well by the time he was 12 or 13. Although Wes did not purchase a regular, six-string, guitar until he was 19 or 20, he had already mastered basic four string chord shapes, hand co-ordination and, perhaps more importantly, further developed an already acute “musical ear”.

Charlie Christian was his initial inspiration t o begin a serious study of the fully-fledged six-string guitar. It was during a local dance, where Wes had taken his newly-wed wife (Serene), that the strains of the Benny Goodman band, with Charlie Christian, made an indelible impression on him.

Shortly afterward, he recklessly spent a hard-earned, and much needed $350 on an electric guitar and amplifier. Wes gradually grew more and more obsessed with the instrument, and in particular with Charlie Christian’s ability to play long streams of eighth notes like a saxophone or trumpet.

Serene recalled that Wes would often get together with his bassist brother Monk, and play right through the night, without even wanting to go to bed. In fact, it w as Serene’s continued complaints, about the volume levels from Wes’ amplifier, that eventually led to his abandonment of the pick.

He told Bill Quinn, in a 1968 Downbeat interview, that “t he sound was too much, even for my neighbors, so I took to a back room in the house and began plucking the strings with the fat part of my thumb. This was much quieter”.

Indeed, Wes related this same story so often during his career, that it appears to be of sound providence. Much of his staggeringly virtuosic thumb technique can be attributed to the fact that he made this decision relatively early on. Once the decision had been made, he was able to develop a proficiency with this unusual technique over a period of two decades.

By the mid-1940s, Wes was playing regularly at an Indianapolis Night Club called CLUB 440, where he apparently cultivated a good rapport with the other musicians, and perhaps more importantly, began to learn about the chord progressions and structure of “standard” tunes.

As he improved, Montgomery spent several short spells on the road, with bands like the Brownskin Models, Snookum Russell and Four Jacks And A King. It wasn’t until 1948, however, that his first big break and indicator of things to come, occurred.

On the morning of May 15th, Wes auditioned for vibes player/ bandleader, Lional Hampton, on the same evening, he left home for a two-year stint on the road with the Hampton band. There had been no prior warning of this prestigious gig and his young wife , Serene, was shocked to fin d him leaving home wit h suitcase and guitar in hand.

The recordings that Montgomery made whilst he was with Hampton reveal how much he was still under the spell of Charlie Christian. The fact that he played such a similar role with Hampton as Christian had done with Goodman, must have strengthened his resolve to be a jazz musician despite the hard work, disappointment and financial insecurity.

On top of the grueling routine, drudgery of travel and haphazard eating schedules, Montgomery had a mortal fear of flying and would drive unimaginable distances between gigs. Understandably, for the above reasons and more, he found that he profoundly disliked everything about life on the road. Finding such protracted spells away from home (and his growing young family) increasingly unpalatable, Montgomery left the Hampton band in 1950, and resigned himself to a full-time career as an arc-welder and a part-time career as a jazz guitarist.

As word got around that Wes was back in tow n, however, he soon found himself even busier than ever, working regular gigs with the Montgomery Johnson Quartet, as well as with his brothers Monk and pianist/ vibes player Buddy. He also worked with several pick-up bands, comprising top local musicians such as David Baker, Eddie Higgins, Leroy Vinegar and Mel Rhyne.

By the mid-fifties Montgomery was holding down a day job, at a car battery plant and a 9.00 pm till 2.00 am nightly gig at the Turf Bar. Whenever there were after-hours jam sessions, at venues like the Missile Room , Hub Hub or Club 10, he would be there also, making the most of the opportunity to stretch out, uncompromisingly, with the modern lines and harmonic concepts he was beginning to develop.

Wes’s musical tastes had moved away from the George Shearing Quintet, who the Montgomery Brothers had initially imitated, towards the more experimental musics of Miles Davis, Horace Silver and John Coltrane.

He was also beginning to compose, the evidence of which could be heard to good effect on MONTGOMERYLAND ( 1958/ 9) which contained no less than five of his original tunes.

During the late 1950s Wes again spent some time away from home, this time to work and record with his brothers in L A. Between 1957 and 1959, his by now mature style had been showcased on no less than five Pacific Jazz albums.

On the last of these, A GOOD GIT TOGETHER, where he was a sideman for vocalist Jon Hendricks, it was another sideman on the session who proactively lifted Montgomery’s career to a higher plateau.

That sideman was alto saxophonist, Cannonball Adderley, who was enjoying great success, both as a leader in his own right, and with the iconoclastic Miles Davis Quintet. Cannonball had heard about Wes from various sources, prior to hearing his organ trio on a late night session at the Missile Room. Completely overwhelmed that such a huge talent should exist in near obscurity, Cannonball became Wes’ chief publicist and mentor.

Within a week, he had convinced Orrin Keepnews, of Riverside Records, to fly down from New York to Indianapolis, where he could see this undiscovered jazz giant for himself. Needless to say, Montgomery was signed on the spot , and his place in the pantheon of jazz guarantied.

Between 1959 and 1963, he recorded 12 superlative albums as leader, or co-leader, and a further 3 as a sideman with Nat Adderley, Harold Land and Cannonball Adderley. These Riverside/ Fantasy recordings constituted a legacy which was to irreconcilably change the future of jazz guitar.

One of the first Riverside albums to obtain “classic” status: THE INCREDIBLE JAZZ GUITAR OF WES MONTGOM ERY (Riverside OJCCD-02 6) , contained four of Wes’ original tunes, two of which (4 on 6 and West Coast Blues) soon became jazz standards.

Wes Mongtomery generally included one or two of his own tunes on albums and live performances. The Jazz Prisma broadcast, recorded on the enclosed video, is typical of his programming; which might include a standard show tune (Here’s That Rain y Day), a jazz standard (John Coltrane’s Impressions) and two originals ( Jingles and Twisted Blues) .

Wes was always a perfectionist, not only in his playing, but also with presentation, repertoire and appearance. David Baker once remarked that, back in the Indianapolis period (1950-59), Wes had been a stickler for rehearsals and would run through passages ad infinitum until he achieved the required results.

The splendidly refined and poli shed ensemble work, between Montgomery’s guitar, Mabern’s piano and t he rhythm section, on the Prisma performance is evidence of thi s meticulous approach which is especially evident in the im agi-native arrangements of Twi sted Blu es and Here’s Tha t Rain y Day.

Jazz Prisma was recorded in Belgium , during the group’s successful 1965 European tour, which also took in Germany, France and England. By this time, Riverside records had run into difficulties and Wes had signed with Verve Records, under the auspices of Creed Taylor. It was Taylor, with extensive experience of best-selling jazz musicians, who put Montgomery into musical settings which appealed to a wider audience.

He told Mike Hennessey, in a Jazz Journal interview, that from the outset he decided to record Montgomery “in a culturally acceptable context.”

Taylor’s culturally acceptable contexts meant big-bands, strings and contemporary “pop” tunes. As a result, albums like GOIN OUT OF MY HEAD (1 9 65 ), TEQUILA (1 9 6 6) and

CALIFORNIA DREAM ING ( 19 6 6) sold in huge quantities, com-pared to the Riverside recordings. This increased success gave Wes a commercial viability, and he became a headliner at Jazz Festivals as well as a featured artist on TV shows such as the Jazz 6 25 (England) , Jazz Prisma (Belgium) and The Hollywood Palace, Steve Allen and Mike Douglas Show s (USA).

Collectively, these broadcasts show Montgomery at the height of his powers. The profound inevitability of his single-lines, amazing fluidity of octave technique and sophistication of harmonic concept, meld together into a mu sic which is virtually perfect yet at the same time never contrived. We are hearing the results of a 25-year process, but those results sound so fresh and natural that it is easy to overlook their cost.

Wes Montgomery had paid hi s dues, as many if not m ore than the next person, but tragically, just as he was about to reap the fruits of his labor, he died from a heart attack at his Indianapolis home on June 15th l968.

In the three decades which have passed since Mongtomery’s untimely death, his influence upon other jazz guitarists remains undiminished. Many characteristics of his style have permeated popular music across all of its diverse strands. On a more concrete level there have been awards, scholarships and count less tributes in his name. Indianapolis honored him by renaming a 34 acre municipal park – WES MONTGOMERY PARK, as well as a Wes Montgomery swimming pool and permanent display of memorabilia (Guitar, gold discs, trophies and Awards) in the Indianapolis Children’s’ museum.

Perhaps the greatest tribute to the man, however, is the reverence in which he i s held by other jazz musicians and in the continued popularity of his recorded legacy. The Jazz Prisma session, shown on this video, is an affirmation of Montgomery’s status as a jazz great.

He was, however, much more than a great jazz guitarist and composer, for his music transcended the instrument and the mechanics of technical accomplishment. Although the guitar was his vehicle, modern jazz was his medium, and in that medium he was as important a voice as the other illustrious names that shaped the music. Important video foot age, such as that seem in the Prisma session, can only further enhance the reputation of this already legendary performer.

Wes Montgomery Live In 65

Track List:

0:00 Blues 5:35 Nica’s dream 14:27 Ni idea 29:26 Impressions 32:53 Twisted blues 38:24 There’s that rainy day 45:34 Jingles 49:33 The girl next door 55:14 Four on six (que temazo lpm) 1:00:00 Full house 1:05:05 There’s that rainy day 1:11:38 Twisted blues