Come join us now, and enjoy playing your beloved music and browse through great scores of every level and styles!

Can’t find the songbook you’re looking for? Please, email us at: sheetmusiclibrarypdf@gmail.com We’d like to help you!

Table of Contents

Browse in the Library:

Or browse in the categories menus & download the Library Catalog PDF:

Gustav Mahler: The 100 most inspiring musicians of all time

Austrian-Jewish composer and conductor Gustav Mahler

(b. July 7, 1860, Kaliště, Bohemia, Austrian Empire [Austria]—d. May

18, 1911, Vienna, Austria) is noted for his 10 symphonies and various

songs with orchestra, which drew together many different strands of Romanticism. Although his music was largely ignored for 50 years after his death, Mahler was later regarded as an important forerunner of 20th-century techniques of composition and an acknowledged influence on such composers as Arnold Schoenberg, Dmitry Shostakovich, and Benjamin Britten.

Early Life

Mahler was the second of 12 children of an Austrian-Jewish tavern keeper living in the Bohemian village of Kaliště (German: Kalischt), in the southwestern corner of the modern Czech Republic. Shortly after his birth the family moved to the nearby town of Jihlava (German: Iglau), where Mahler spent his childhood and youth. Mahler was afflicted by the tensions of being an “other” from the beginning of his life. As part of a German-speaking Austrian minority, he was an outsider among the indigenous

Czech population and, as a Jew, an outsider among that Austrian minority; later, in Germany, he was an outsider as both an Austrian from Bohemia and a Jew.

Mahler’s life was also complicated by the tension between his parents. His father had married a delicate woman from a cultured family, and, coming to resent her social superiority, he resorted to physically maltreating her.

In consequence Mahler was alienated from his father and had a strong mother fixation. Furthermore, he inherited his mother’s weak heart, which was to cause his death at the age of 50. This unsettling early background may explain the nervous tension, the irony and skepticism, the obsession

with death, and the unremitting quest to discover some meaning in life that was to pervade Mahler’s life and music.

Mahler’s musical talent revealed itself early and significantly; around the age of four he began to reproduce military music and Czech folk music on the accordion and on the piano and began composing pieces of his own. The military and popular styles, together with the sounds of nature, became main sources of his mature inspiration. At 10 he made his debut as a pianist in Jihlava and at 15 was so proficient musically that he was accepted as a pupil at the Vienna Conservatory. After winning piano and

composition prizes and leaving with a diploma, he supported himself by sporadic teaching while trying to win recognition as a composer.

When he failed to win the Conservatory’s Beethoven Prize for composition with his first significant work, the cantata Das klagende Lied (completed 1880; The Song of Complaint), he turned to conducting for a more secure livelihood.

Career as a Conductor

The next 17 years saw his ascent to the very top of his chosen profession. From conducting musical farces in Austria, he rose through various provincial opera houses to become artistic director of the Vienna Court Opera in 1897, at the age of 37. As a conductor he had won general

acclaim, but as a composer, during this first creative period, he encountered the public’s lack of comprehension that was to confront him for most of his career.

Since Mahler’s conducting life centred in the traditional manner on the opera house, it is at first surprising that his whole mature output was entirely symphonic (his 40 songs are not true lieder but embryonic symphonic movements, some of which, in fact, provided a partial basis for the symphonies). But Mahler’s unique aim, partially influenced by the school of Richard Wagner and Franz Liszt, was essentially autobiographical—the musical expression of a personal view of the world, particularly through song and symphony.

Musical Works: First Period

Each of Mahler’s three creative periods produced a symphonic trilogy. The three symphonies of his first period were conceived on a programmatic basis (i.e., founded on a nonmusical story or idea), the actual programs (later discarded) being concerned with establishing some ultimate ground for existence in a world dominated by pain, death, doubt, and despair.

To this end, he followed the example of Ludwig van Beethoven’s Symphony No. 6 in F Major (Pastoral) and Hector Berlioz’s Symphonie fantastique in building symphonies with more than the then-traditional four movements; that of Wagner’s music-dramas in expanding the time span, enlarging the orchestral resources, and indulging in uninhibited emotional expression; that of Beethoven’s Symphony No. 9 in D Minor (Choral) in introducing texts sung by soloists and chorus; and that of certain chamber works by Franz Schubert in introducing music from his own songs (settings of poems from the German folk anthology Des Knaben Wunderhorn [The Youth’s Magic Horn] or of poems by himself in a folk style).

These procedures, together with Mahler’s own tense and rhetorical style, phenomenally vivid orchestration, and ironic use of popular-style music, resulted in three symphonies of unprecedentedly wide contrasts but unified by his firm command of symphonic structure. The program of the purely orchestral Symphony No. 1 in D Major (1888) is autobiographical of his youth: the joy of life becomes clouded over by an obsession with death. The five-movement Symphony No. 2 (1894; popular title

Resurrection) begins with the death obsession and culminates in an avowal of the Christian belief in immortality, as projected in a huge finale portraying the Day of Judgment and involving soloists and chorus.

The even vaster Symphony No. 3 in D Major (1896), also including a soloist and chorus, presents in six movements a Dionysiac vision of a great chain of being, moving from inanimate nature to human consciousness and the redeeming love of God.

The religious element in these works is highly significant. Mahler’s disturbing early background, coupled with his lack of an inherited Jewish faith (his father was a freethinker), esulted in a state of metaphysical torment, which he resolved temporarily by identifying himself with

Christianity. That this was a genuine impulse there can be no doubt, even if there was an element of expediency in his becoming baptized, early in 1897, because it made it easier for him to be appointed to the Vienna Opera post.

The 10 years there represent his more balanced middle period. His newfound faith and his new high office brought a full and confident maturity, which was further stabilized by his marriage in 1902 to Alma Maria Schindler, who bore him two daughters, in 1902 and 1904.

Musical Works: Middle Period

As director of the Vienna Opera, Mahler achieved an unprecedented standard of interpretation and performance, and through a number of concert tours he also became famous over much of Europe as a conductor. He continued his recently acquired habit of devoting his summer vacations, in the Austrian Alps, to composing, and, since, in his case, this involved a ceaseless expenditure of spiritual and nervous energy, he placed an intolerable strain on his frail constitution.

Most of the works of this middle period reflect the fierce dynamism of Mahler’s full maturity. An exception is Symphony No. 4 (1900; popularly called Ode to Heavenly Joy), which has a song finale for soprano that evokes a naive peasant conception of the Christian heaven. At the same

time, in dispensing with an explicit program and a chorus and coming near to the normal orchestral symphony, it does foreshadow the purely orchestral middle-period trilogy, Nos. 5, 6, and 7. No. 5 (1902; popularly called Giant) and No. 7 (1905; popularly called Song of the Night) move from darkness to light, though the light seems not the illumination of any afterlife but the sheer exhilaration of life on Earth.

Between them stands the work Mahler regarded as his Tragic Symphony—the four-movement No. 6 in A Minor (1904), which moves out of darkness only with difficulty, and then back into total night. From these three symphonies onward, he ceased to adapt his songs as whole sections or

movements, but in each he introduced subtle allusions, either to his Wunderhorn songs or to his settings of poems by Friedrich Rückert, including the cycle Kindertotenlieder (1901–04; Songs on the Deaths of Children).

At the end of this period he composed his monumental Symphony No. 8 in E-flat Major (1907) for eight soloists, double choir, and orchestra—a work known as the Symphony of a Thousand, owing to the large forces it requires, though Mahler gave it no such title; it constitutes the first

continuously choral and orchestral symphony ever composed. The first of its two parts, equivalent to a symphonic first movement, is a setting of the medieval Catholic Pentecost hymn Veni Creator Spiritus; part two, amalgamating the three movement-types of the traditional symphony, has for its text the mystical closing scene of J.W. von Goethe’s Faust drama (the scene of Faust’s redemption).

The work marked the climax of Mahler’s confident maturity, since what followed was disaster—of which, he believed, he had had a premonition in composing his Tragic Symphony, No. 6. The finale originally contained three climactic blows with a large hammer, representing “the three blows of fate which fall on a hero, the last one felling him as a tree is felled” (he subsequently removed the final blow from the score). Afterward he identified these as presaging the three blows that fell on himself in 1907, the last of which portended his own death: his resignation was demanded at the Vienna Opera, his threeyear- old daughter, Maria, died, and a doctor diagnosed his fatal heart disease.

Musical Works: Last Period

Thus began Mahler’s last period, in which, at the age of 47, he became a wanderer again. He was obliged to make a new reputation for himself, as a conductor in the United States, directing performances at the Metropolitan Opera and becoming conductor of the Philharmonic Society of New York; yet he went back each summer to the Austrian countryside to compose his last works. He returned finally to Vienna, to die there, in 1911.

The three works constituting his last-period trilogy, none of which he ever heard, are Das Lied von der Erde (1908; The Song of the Earth), Symphony No. 9 (1910), and Symphony No. 10 in F Sharp Major, left unfinished in the form of a comprehensive full-length sketch (though a fulllength performing version has been made posthumously).

Beginning as a song cycle, it grew into “A Symphony for Tenor, Baritone (or Contralto) and Orchestra.” Yet, he would not call it “Symphony No. 9,” believing, on the analogy of Beethoven and Bruckner, that a ninth symphony must be its composer’s last. When he afterward began the actual No. 9, he said, half jokingly, that the danger was over, since it was “really the tenth”; but in fact, that symphony became his last, and No. 10 remained in sketch form when he died.

This last-period trilogy marked an even more decisive break with the past than had the middle-period trilogy. It represents a threefold attempt to come to terms with modern man’s fundamental problem—the reality of death, which in his case had effectively destroyed the religious faith he had opposed to death as an imagined event. Das Lied von der Erde—a six-movement “song-cycle symphony” No. 8—views the evanescence of all things human, finding sad consolation in the beauty of the Earth that endures after the individual is no longer alive to see it.

In the four-movement No. 9, purely orchestral, the confrontation with death becomes an anguished personal one, evoking horror and bitterness in Mahler’s most modern and prophetic movement, the Rondo-Burleske,

and culminating in a finale of heartbroken resignation. Growing familiarity with the sketch of No. 10, however, has suggested that he later broke through to a more positive attitude. The five movements of this symphony deal with the same conflict as the two preceding works, but the resignation attained at the end of the finale is entirely affirmative.

Best classical sheet music download.

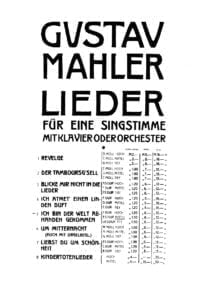

Best of Gustav Mahler

Tracklist:

Tracklist: Sinfonia Nº 1 Em Ré Maior, “Titã” 1. Langsam, Schleppend 2. Kraftig, Bewegt 3. Feierlich Und Gemessen, Ohne Zu Schleppend 4. Sturmisch Bewegt Royal Philharmonic Orchestra

Please, subscribe to our Sheet Music Library.

If you are already a subscriber, please, check our NEW SCORES’ page every month for new sheet music. THANK YOU!