Come join us now, and enjoy playing your beloved music and browse through great scores of every level and styles!

Can’t find the songbook you’re looking for? Please, email us at: sheetmusiclibrarypdf@gmail.com We’d like to help you!

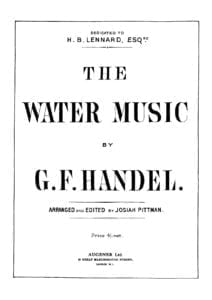

Sarabande (piano solo) – G. F. Händel from Suite no. 4 in D Minor, HWV 437 with sheet music download.

Please, subscribe to our Library.

If you are already a subscriber, please, check our NEW SCORES’ page every month for new sheet music. THANK YOU!

Best Sheet Music download from our Library.

| George Frideric Handel – Georg Friedrich Händel (Composer) |

| Born: February 23, 1685 – Halle (Saale), Saxony-Anhalt, Germany Died: April 14, 1759 – London, England |

| Georg [George] Frideric [Friderick, Frederic, Frederick] Handel [Haendel, Hendel] was a German-born Baroque composer who is famous for his operas, oratorios and concerti grossi. Born as Georg Friedrich Händel in Halle, he spent most of his adult life in England, becoming a subject of the British crown on January 22, 1727. His most famous works are Messiah, an oratorio set to texts from the King James Bible; Water Music; and Music for the Royal Fireworks. Strongly influenced by the techniques of the great composers of the Italian Baroque and the English composer Henry Purcell, his music was known to many significant composers who came after him, including Haydn, W.A. Mozart, and L.v. Beethoven. |

| Biography |

| George Frideric Handel was born as Georg Friedrich Händel in Halle in the Duchy of Magdeburg (province of Brandenburg-Prussia) to Georg and Dorothea (née Taust) Händel in 1685, the same year that both J.S. Bach and Domenico Scarlatti were born. Handel displayed considerable musical talent at an early age; by the age of seven he was a skilful performer on the harpsichord and pipe organ, and at nine he began to compose music. However, his father, a distinguished citizen of Halle and an eminent barber-surgeon who served as valet and barber to the Courts of Saxony and Brandenburg, was opposed to his son’s wish to pursue a musical career, preferring him to study law. By contrast, Handel’s mother, Dorothea, encouraged his musical aspirations. Nevertheless, the young Handel was permitted to take lessons in musical composition and keyboard technique from Friedrich Wilhelm Zachow, the organist of the Liebfrauenkirche, Halle. For his seventh birthday his aunt, Anna, gave him a spinet, which was placed in the attic so that Handel could play it whenever he could get away from his father. In 1702, following his father’s wishes, G.F. Handel began the study of law at the University of Halle, but after his father’s death the following year, he abandoned law for music, becoming the organist at the Protestant Cathedral. In 1704, he moved to Hamburg, accepting a position as violinist and harpsichordist in the orchestra of the opera house. There, he met Johann Mattheson, Christoph Graupner and Reinhard Keiser. His first two operas, Almira and Nero, were produced in 1705. Two other early operas, Daphne and Florindo, were produced in 1708. During 1706-1709, G.F. Handel travelled to Italy at the invitation of Gian Gastone de’ Medici, and met Medici’s brother Ferdinando, a musician himself. While opera was temporarily banned at this time by the Pope, Handel found work as a composer of sacred music; the famous Dixit Dominus (1707) is from this era. He wrote many cantatas in operatic style for gatherings in the palace of Pietro Ottoboni (cardinal). His Rodrigo was produced in Florence in 1707, and his Agrippina at Venice in 1709. Agrippina, which ran for an unprecedented 27 performances, showed remarkable maturity and established his reputation as an opera composer. Two oratorios, La Resurrezione and Il Trionfo del Tempo, were produced in Rome in a private setting for Ruspoli and Ottoboni in 1709 and 1710, respectively. In 1710, G.F. Handel became Kapellmeister to George, Elector of Hanover, who would soon be King George I of Great Britain. He visited Anna Maria Luisa de’ Medici on his way to London in 1710, where he settled permanently in 1712, receiving a yearly income of £200 from Queen Anne. During his early years in London, one of his most important patrons was the young and wealthy Richard Boyle, 3rd Earl of Burlington, who showed an early love of his music. Handel spend the most carefree time of his life at Cannons and laid the cornerstone for his future choral compositions in the twelve Chandos Anthems. Romain Rolland states that these anthems were as important for his oratorios as the cantates for his operas. He highly estimates also Acis and Galatea, like Winton Dean, who writes the music catches breath and disturbs the memory. During Handel’s life time it was his most performed work. In 1723 G.F. Handel moved into a newly built house at 25 Brook Street, London, which he rented until his death in 1759. This house is now the Handel House Museum, a restored Georgian house open to the public with an events programme of Baroque music. There is a blue commemorative plaque on the outside of the building. It was here that he composed Messiah, Zadok the Priest and Music for the Royal Fireworks. (In 2000, the upper stories of 25 Brook Street were leased to the Handel House Trust, and after an extensive restoration program, the Handel House Museum opened to the public on November 8, 2001.) In 1726 G.F. Handel’s opera Scipio (Scipione) was performed for the first time, the march from which remains the regimental slow march of the British Grenadier Guards. He was naturalised a British subject in the following year. In 1727 G.F. Handel was commissioned to write four anthems for the coronation ceremony of King George II. One of these, Zadok the Priest, has been played at every British coronation ceremony since. Handel was director of the Royal Academy of Music from 1720 to 1728, and a partner of J.J. Heidegger in the management of the King’s Theatre from 1729 to 1734. Handel also had a long association with the Royal Opera House at Covent Garden, where many of his Italian operas were premiered. In April 1737, at age 52, he suffered a stroke or some other malady which left his right arm temporarily paralysed and stopped him from performing. He also complained of difficulties in focusing his sight. Handel went to Aix-la-Chapelle, taking hot baths and playing organ for the audience. Handel gave up operatic management entirely in 1740, after he had lost a fortune in the business. Following his recovery, G.F. Handel focused on composing oratorios instead of opera. Handel’s Messiah was first performed in New Musick Hall in Fishamble Street, Dublin on April 13, 1742, with 26 boys and five men from the combined choirs of St Patrick’s and Christ Church cathedrals participating. In 1749 he composed Music for the Royal Fireworks; 12,000 people came to listen. Three people died, including one of the trumpeters on the day after. In 1750 G.F. Handel arranged a performance of Messiah to benefit the Foundling Hospital. The performance was considered a great success and was followed by annual concerts that continued throughout his life. In recognition of his patronage, Handel was made a governor of the Hospital the day after his initial concert. He bequeathed a fair copy of Messiah to the institution upon his death. His involvement with the Foundling Hospital is today commemorated with a permanent exhibition in London’s Foundling Museum, which also holds the Gerald Coke Handel Collection. In August 1750, on a journey back from Germany to London, G.F. Handel was seriously injured in a carriage accident between The Hague and Haarlem in the Netherlands. In 1751 his eyesight started to fail in one eye. The cause was unknown and progressed into his other eye as well. He died some eight years later, in 1759, in London, his last attended performance being his own Messiah. More than three thousand mourners attended his funeral, which was given full state honours, and he was buried in Westminster Abbey. G.F. Handel never married, and kept his personal life very private. Unlike many composers, he left a sizable estate at his death – worth £20,000 (an enormous amount for the day), the bulk of which he left to aniece in Germany – as well as gifts to his other relations, servants, friends and to favourite charities. |

| Works |

| See: List of compositions by George Frideric Handel (Wikipedia) |

| George Frideric Handel’s compositions include 42 operas; 29 oratorios; more than 120 cantatas, trios and duets; numerous arias; chamber music; a large number of ecumenical pieces; odes and serenatas; and sixteen organ concerti. His most famous work, the Messiah oratorio with its “Hallelujah” chorus, is among the most popular works in choral music and has become a centerpiece of the Christmas season. Also popular are the Op. 3 and Op. 6 Concerti Grossi, as well as “The Cuckoo and the Nightingale”, in which birds are heard calling during passages played in different keys representing the vocal ranges of two birds. Also notable are his sixteen keyboard suites, especially The Harmonious Blacksmith. G.F. Handel introduced various previously uncommon musical instruments in his works: the viola d’amore and violetta marina (Orlando), the lute (Ode for St. Cecilia’s Day), three trombones (Saul), clarinets or small high cornets (Tamerlano), theorbo, French horn (Water Music), lyrichord, double bassoon, viola da gamba, bell chimes, positive organ, and harp (Giulio Cesare, Alexander’s Feast). G.F. Handel’s works have been catalogued and are commonly referred to by a HWV number. For example, Handel’s Messiah is also known as HWV 56. |

| Legacy |

| After his death, George Frideric Handel’s Italian operas fell into obscurity, save for selections such as the ubiquitous aria from Serse, “Ombra mai fu”. His reputation throughout the 19th century and first half of the 20th century, particularly in the Anglophone countries, rested primarily on his English oratorios, which were customarily performed by enormous choruses of amateur singers on solemn occasions. These include Esther (1718); Athalia (1733); Saul (1739); Israel in Egypt (1739); Messiah (1742); Samson (1743); Judas Maccabaeus (1747); Solomon (1748); and Jephtha (1752). His best are based on a libretto by Charles Jennens. Since the 1960’s, with the revival of interest in Baroque music, original instrument playing styles, and the prevalence of countertenors who could more accurately replicate castrato roles, interest has revived in Handel’s Italian operas, and many have been recorded and performed onstage. Of the fifty he wrote between 1705 and 1738, Agrippina (1709), Rinaldo (1711, 1731), Orlando (1733), Alcina (1735), Ariodante (1735), and Serse (1738, also known as Xerxes) stand out and are now performed regularly in opera houses and concert halls. Arguably the finest, however, are Giulio Cesare (1724) and Rodelinda (1725), which, thanks to their superb orchestral and vocal writing, have entered the mainstream opera repertoire. Also revived in recent years are a number of secular cantatas and what one might call secular oratorios or concert operas. Of the former, Ode for St. Cecilia’s Day (1739) (set to texts of John Dryden) and Ode for the Birthday of Queen Anne (1713) are particularly noteworthy. For his secular oratorios, Handel turned to classical mythology for subjects, producing such works as Acis and Galatea (1719), Hercules (1745), and Semele (1744). In terms of musical style, particularly in the vocal writing for the English-language texts, these works have close kinship with the above-mentioned sacred oratorios, but they also share something of the lyrical and dramatic qualities of Handel’s Italian operas. As such, they are sometimes performed onstage by small chamber ensembles. With the rediscovery of his theatrical works, Handel, in addition to his renown as instrumentalist, orchestral writer, and melodist, is now perceived as being one of opera’s great musical dramatists. G.F. Handel has generally been accorded high esteem by fellow composers, both in his own time and since. J.S. Bach apparently said “[Handel] is the only person I would wish to see before I die, and the only person I would wish to be, were I not Bach.” W.A. Mozart is reputed to have said of him, “Handel understands effect better than any of us. When he chooses, he strikes like a thunder bolt” and to L.v. Beethoven he was “the master of us all…the greatest composer that ever lived. I would uncover my head and kneel before his tomb.” The latter emphasised above all the simplicity and popular appeal of Handel’s music when he said, “Go to him to learn how to achieve great effects, by such simple means.” He is commemorated as a musician in the Calendar of Saints of the Lutheran Church on July 28, with J.S. Bach and Heinrich Schütz. G.F. Handel’s works were edited by Samuel Arnold (40 vols., London, 1787–1797), and by Friedrich Chrysander, for the German Händel-Gesellschaft (100 vols., Leipzig, 1858–1902). Handel adopted the spelling “George Frideric Handel” on his naturalisation as a British subject, and this spelling is generally used in English-speaking countries. The original form of his name (Georg Friedrich Händel) is generally used in Germany and elsewhere, but he is known as “Haendel” in France, which causes no small amount of grief to cataloguers everywhere. There was another composer with a similar name, Handl, who was a Slovene and is more commonly known as Jacobus Gallus. |

| J.S. Bach Connection |

| Although born within a few weeks, and quite a short distance, of each other, J.S. Bach and George Frideric Handel never met. In 1719 J.S. Bach did travel to Halle in the hope of a meeting, but Handel had left by the time he arrived; again in 1729, when Handel was once more in his native city, J.S. Bach sent his son Wilhelm Friedemann Bach to invite Handel to Leipzig, but Handel was unable to make the journey. In a quite extraordinary way the music of these two greatest of late Baroque composers shows few meeting-points either. J.S. Bach excelled in genres, such as the church cantata, oratorio Passion, mass, and Vivaldi-type concerto, that Handel barely touched; Handel’s greatest achievements were in opera, oratorio, and the Corelli-type concerto-genres uncultivated by J.S. Bach. Where their interests did overlap-in the keyboard suite and instrumental sonata-their styles differed greatly. The solo keyboard sonata they left almost entirely to the third member of the 1685 triumvirate, Domenico Scarlatti. |

Browse in the Library:

Or browse in the categories menus & download the Library Catalog PDF: