Browse in the Library:

Or browse in the categories menus & download the Library Catalog PDF:

What is Jazz Improvisation? Keith Jarrett – A musical analysis of “My Funny Valentine”(2/2)

The introduction

The essential character here is one of a folk-like quality (with its preponderance of chords derived from the Aeolian mode and harmonic movement centered around the tonic) combined with classical elements (attention to detail in the voices, and the use of chords in their first

inversion), jazz voicings, and bars of different lengths, which give it a contemporary edge.

There is a strong sense of it being improvised in the moment, and this, coupled with the fact that (except for two brief ritardandos) it is played at a moderate tempo throughout, gives it much forward momentum. It builds towards a climax of fast moving chords, which occurs near the end, and then gradually winds down before concluding and moving into the main piece.

There is no obvious reference to the melody or the verse of the song, rather an approach that sounds like a “Fantasy inC minor”, where the main key of the song is freely explored.

Form and Melody

It is seventy bars in length, runs for approximately two minutes and fifteen seconds, and has a form which is comprised of five main sections that are separated by cadences. It is as follows:

1st section: 7 bars;

2nd section: 5 bars;

3rd section: 1 0 bars;

4th section: 23 bars;

5th section: 25 bars;

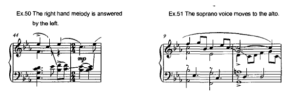

A cohesive form is achieved by the use of definite melodic episodes within the sections, and these are again, based on rhythmic motifs which provide the core thematic material. These episodes (except for one instance at bars 44 and 45 where the left-hand answers the right [see ex.50)) are all found in the right-hand part, but often the melodies move from the soprano voice to the first or second alto (as in bars 9 and 10 [see ex.51], 21-25, 33 and 34 etc.) while the soprano continues with longer or sustained notes, thus adding a certain contrapuntal sophistication to the sound.

There is no obvious pattern in the lengths or groupings of the episodes, and they vary in length from three bars to nine. The most prominent motif is “A”, and it is utilized in a number of ways. The episodes will be described as before, and are as follows:

1st section:

Bars 1-3, 1″1 episode :-This is based on motif “A” (see ex.52). After it is first stated (bar 2 [the figure in bar 1 is a pickup]), it is repeated (bar 3);

Bars 4-7, 2″‘ episode :-This is based on motif “B” (see ex. 52). After it is first stated (bar 4), it is repeated twice (bars 5,6 [at 6 it is lengthened by a quaver and leads to the cadence figure at bar 7). The figure at the end of 7 is a connecting phrase to the next section;

2nd section:

Bars 8-12, only episode:- This is based on motif “C” (see ex.52). After it is first stated (bar 9 [the figure in 8 is a pick up]), it is repeated (bar 10 [it is effectively shortened by a crotchet), then it is played in slightly truncated form (bars 11, 12);

3rd section:

Bars 13 and 14, opening phrase. Bars 15-18, 1’1 episode:- This is based on motif “C1” (see ex.52). After it is first stated (bar 15 (includes quaver pick up from previous bar]), it is played in truncated and more syncopated fonm (bar 16), then permutated through a change to 3/4 (bars 17, 18);

Bars 19-22, 2″‘ episode:- This is based on motif “C”. After it is first stated (bar 19 [incl. quaver pick up from prev. bar, first note is lengthened by a quaver)), it is repeated (bar 21 [figure at bar 20 is a connecting phrase]);

4′” section:

Bars 23-25, 1 ‘1 episode :- This is based on motif “C”. After it is first stated (bar 23 [incl. quaver pick up from prev. bar, last note is lengthened by a quaver]), it is repeated (bar 25 [pick up in 24 is longer]); Bars 26-34, 2nd episode :- This is based on motif “D” (see ex.52). After it is first stated (bars 26,27), it is displaced (it’s quaver pick up is on 2+ rather than 1 + ), lengthened by a crotchet and repeated twice (bars 28-31 [incl. quaver and crotchet pick up from prev. bar]). The figure at 32,33 is a cadential phrase derived from “D”. The figure at 34 is derived from “C”; Bars 35-37, 3″‘ episode :-The figure in bar 35 is a connecting phrase. This is based on motif “E” (see ex.52). After it is first stated (bar 36 [does not include first crotchet]), it is displaced (the quaver pick up is on 1 + rather than 2) and shortened by a quaver (bar 37); Bars 38-41, 4′” episode :-This is based on motif “A”. After it is first stated (beat 3 of 38, beat 1 of 39), it is repeated (bar 41 [the figure at 39,40 is a connecting phrase]); The figure at the end of 41,42 is a connecting phrase. Bars 43-45, 5′” episode : This combines motif “F” (see ex. 52) at bar 43 with a cadence figure which is played twice (bars 44,45 [note how this is the same as the one at bar 7]);

5th section:

Bars 46-54, 1″ episode :- Begins with what is essentially motifs “F” and “A” combined (bars 46,47 [“F” has a quaver pick up added to it]) and which will now be called “A1” (see ex.52). This is then repeated (bars 48,49 [pick up from prev. bar is lengthened by 2 quavers]), then shortened

by a crotchet as part of a change to 3/4 and repeated twice (bars 50-53 [incl. pick up from prev. bar, ]), then played in 4/4 but shortened by a crotchet (bar 54 [pick up from prev. bar is 5 quavers]); Bars 55-57, climactic passage (essentially all quavers). Bars 58-63, 2″• episode :-This is based on motifs “A1” and “A”. “A1” is played (bars 58,59), then “A” is played (bar 60 [incl. pick up from prev. bar]), then “A” is displaced (the first quaver is on the last beat of the bar rather than the first) and played 3 times (starts on beat 3 of 60, end on beat 1 of 63); Bars 64-70, 3″‘ episode:- This is based on motif “A”. After it starts (beat 2 of 63), it is repeated 5

times in various rhythmic permutations which involve changing time signatures;

The above analysis clearly shows the solidity of the structural foundation, and it is this, combined with the spontaneity and emotional depth that Jarrett brings to the proceedings, that makes the introduction so successful. This kind of balance was touched upon by Yehudi Menuhin in his description of Bach’s music- “However passionate it may become, there is a/ways form … “

It is also worth noting that except for bars 26, 27, 49, and bars 64-69, the entire melody is created using the Aeolian scale.

Rhythm

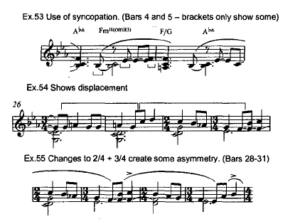

As mentioned earlier, apart from brief ritardandos at bars 12 and 68, it is played in tempo, and the impression of rhythmic simplicity that one might get upon first hearing is shown, upon close examination to be rather deceptive, as there is much variety here. This is achieved by substantial use of syncopation (as in bars 4-7 [see ex.53], 14-16, 19-22 etc.), space (bars 3

and 4, 12, 24, 66-70), and again (and most importantly), both the utilization of varied time signatures and the rhythmic manipulation of the aforementioned motifs.

The manipulation, once more, is achieved by the use of augmentation, diminution, and permutation via changed meters, but in this case, also through the use of a number of displacements. These, (as can be seen from the analysis of the episodes above) can be found at bars 26-29 (see ex.54),

36,37, and 60-63.

Again, there is much shifting from 414 to 314, and vice versa (bars til-17, 53-54 etc.), and the changes to 214 + 314 and 514, though creating some asymmetry (see ex.55), tend to be overshadowed by the displacements in this regard. Here again, Jarrett displays a sense of rhythmic flexibility, and freedom with phrasing, and it is hard not to think of his experience as a drummer. He once said “I’ve been playing drums all my life … lt’s really my first instrument!”

Harmony

As mentioned earlier, this introduction is centered very firmly around the tonic key of C minor, the only real modulation being a fleeting move to C major at bars 25 and 26, which of course reiterates the tonic further (see ex.62). The tonic chord of the relative major, E flat, is used a number of times from bar 23 onwards, and there is a brief chromatic shift to an E flat minor chord at bar 49, but these function only as passing chords (see ex.62).

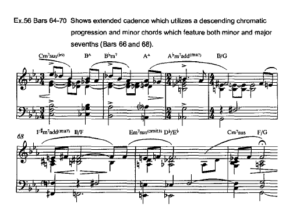

Before looking at the bulk of the harmonic content, one other component is also worthy of mention, and that is the final passage which begins at bar 64 (see ex. 56). Even though it contains a number of notes that are outside of the Aeolian scale in its melody, and its hanmony descends chromatically, the fact that it starts on the tonic, with a tonality that has been so well established means it functions simply as a contrasting, extended cadence.

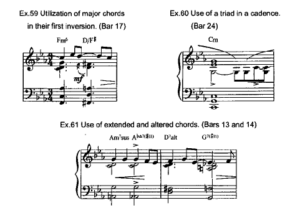

The most predominant chords used are I, VI, IV, and V, and the fact that they often include suspensions (emphasizing the intervals of the fourth and the fifth) contributes very much to the aforementioned folk-like, modal quality (see ex.57). The frequent use of the leading note (B

natural) in the V chord (bars 12, 18, and 22) however, the utilization of major chords in their first inversion (bars 17, 25, 32, 35, 37, 40 and 41), and the use of triads in some cadences (bars 24 and 26) tend to reflect more upon the classical tradition (see exs. 58-60). The influence of the jazz

tradition is probably most obvious in the use of extended and altered chords (see ex.61 ).

The harmonic progressions follow patterns that are typical of western music in general, although the previously mentioned passage at bar 64 is perhaps more jazz influenced. (Note its use of dissonant chords, particularly the ones at bars 66 and 68 where the minor chords feature both minor and major sevenths [see ex.56].) The most frequently used pattern is VI, IV, V (bars 3-6, g,10, 19, 20 etc.), which sometimes resolves to I, but usually moves on to another chord, most often VI (e.g. see bar 5 in ex.62). The II V progression, so common in jazz, features a number of

times {bars 11,12, 14-16 etc.) but again, only sometimes resolves to the tonic (e.g. see bars 14- 16 in ex.62).

There are a couple of step-wise progressions, the short one at bars 23-26 also being a sequence, which facilitates the brief modulation to C major. The longer one begins at bar 52, and except for skipping the seventh degree of the scale at 53, it descends scale-wise and is very effective in setting up the climax which occurs at bar 55 (for both of these see ex.62). As well as the aforementioned passage at bar 64 (which utilizes a descending chromatic pattern that actually starts at bar 62), there is one other section which uses a chromatic progression, but on this occasion it is an ascending one. It starts at bar 35 and continues through to the beginning of 42, and unlike the passage at bar 64 utilizes chords which are all closely related to the tonic key (see ex.62). It is important to note how these two sections, along with the previously mentioned one at bar 52, contribute to the drama and overall shape of the introduction.

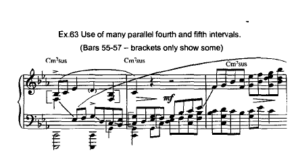

It is worth noting that the climactic passage from bars 55-57 utilizes many parallel fourth and fifth intervals in its chords, and this, of course, tends to emphasize the modal, folk-like flavor (see ex.63).

Opening melody section

The first four bars of the song are played at a moderately slow tempo by the piano only, and act as a transition between the introduction and the rendering of the piece by the ensemble and here, Jarrett uses an ascending line progression in the accompaniment rather than the more common descending one (see the chord chart that accompanies the transcriptions).

The ensemble enters at bar 5 with a straight eighths feel, and the song is given a fairly free reading, with the piano utilizing a single right-hand line accompanied by left-hand chords, and the band playing quite sparsely. The harmony, in comparison with the chord changes that tend to be used (again, see the chord chart ) is slightly simplified, with the 4 bar C minor

sequence that is central to the song being played (except for the first four bars) as C minor, G 7, C minor, F 7, instead of the descending chromatic sequence, the chords at bars 5 and 6, and 13 and 14 being played as just F minor rather than Ab major, F minor, and the chords in the first half of the bridge (bars 17-20) being played as Eb, Bb 7, Eb, rather than Eb, F min., Eb/G, F min. etc. (Note the use in bar 15 of the common substitution where B major replaces Ab minor, and the Eb dim. add 9 harmony in bar 19 which creates a darker sound than the usual major chord.)

The melody (once the band has entered) is played very freely, and is subjected to rhythmic variation (bars 5-6 etc.), paraphrasing (bars 9-12 etc.), or departed from completely, as in bars 14-20. The melodic material here becomes part of a rhythmic episode which features the use of a displaced figure, this involving the manipulation of the motif (two crotchets followed by a minim) that occurs in bar 15. This motif (its minim is shortened to a dotted crotchet) of two and a half beats in length is played successively over a number of bars, and of course falls in different places in relation to the ground beat.

This, in combination with the support of the left-hand chords and the bass’s off-beat figures, creates a suspended feeling and much rhythmic tension. Bill Evans said this about his own use of rhythmn displacement – “… the displacement of phrases, and the way phrases follow one another, and their placement against the meter and so forth, is something that I’ve worked on rather hard … “

The tension is released at bar 21, where the melody (though altered melodically and rhythmically) is returned to, followed then at bar 25 by another paraphrase, this time utilizing block chords. These are played mainly in dotted crotchet rhythms, are almost all off the beat, and create a climax which lasts until bar 33, where the melody is briefly stated before the solo break begins at bar 34.

Piano solo

It is three choruses long (108 bars), and runs for approximately three and a half minutes. The overall shape is as follows:

– First chorus – moderately slow tempo, melody occasionally alluded to, comparatively sparse, builds slowly towards the second; Second chorus- double time feel (continues for the rest of the solo), no obvious reference to the melody, becomes busier, more intense and builds to a high point at the end; Third chorus -double time feel, intensity sustained but kept in check before building to climax, winds down.

Form

Again, form is achieved mainly by the combination of broad shapes that has been described above. (Note that, like before, the high points [bars 66- 70 and 97-104] both use the very high register.) Once more, there is not any sustained use of a particular motif or theme, but instead, a sense of the solo being through composed.

There are again, however, many thematic episodes here, and once more they tend to assist with the overall development of the solo, and sometimes facilitate changes in intensity (e.g. bars 49-51[see ex.64], 64-66). On the whole, they tend to be relatively short and are generally two to four bars long (bars 17- 20, 29- 32, 57 (beat 2)- 58, 81-83 etc.). There is one longer one and this can be found at bars 3-12 where the figure in bar 4 is utilized in bars 9-12 (see ex.65).

It seems clear when looking at the profile of this solo and Stella by Starlight’s that Jarrett is manipulating the shape of the improvisation with great awareness, as he goes along. Another comment of his further illuminates this – ” … when I’m playing I think in terms of structure, but a

very fluid structure that could change at any instant.”

Rhythm

The overall impression here is again one of flexibility, and once more, there is much variety in terms of the different rhythms and their combinations, the lengths of phrases, where the phrases begin and end in relation to the bar lines, and the phrases’ relationship to the beat.

A good example of the variety of rhythms and their combinations can again be found at the beginning of the solo, this time in the first twelve bars (see ex.66). Of particular note is the opening phrase (bars 1 and 2 alone containing crotchets, quavers, a quaver triplet, and semiquavers),

and the succession of anticipated quavers at bars 5 and 6. Other examples can be found at bars 20-26, 29-35, 37-47, 61-66 etc. The phrases vary in length from half a bar (bars 47, 65, 72 etc.), to five and a half bars (bars 91-96), but once more, they tend in general to be one or two bars long. Where they begin and end in relation to the bar lines again shows

Jarrett’s flexibility, and this will be illustrated as before, by examining the first sixteen bars (also see ex.66).- First phrase:- starts on 4+, ends on 1; Second p])rase:- starts on 2+, ends on 1; Third phrase:- starts on 3+, ends on 2+; Fourth phrase:- starts on 2+, ends on 1; Fifth phrase:- starts on 2, ends on 3; Sixth phrase:- starts on 3+, ends on 4+; Seventh phrase:starts

on 1, ends on 4; Eighth phrase:- starts on 4+, ends on 2+; Ninth phrase:- starts on 4, ends on 2.

Once more, the above example also shows some of the syncopation present, and in this case it is considerable. When we look within those same phrases, there is also much to be found, and this is reinforced by the few accents here, which favour the off beats. In general however, the accents in the lines tend to be both on and off the main beats.

There are three other important aspects here, and the first of these is the occasional use of displaced figures. They all vary a little from one another, but tend (as previously mentioned) to make the time sound as though it was turned around. These can be found in bars 14,15, 29,30, 49-51 (see ex.68), 64-66, and 77-79. The second, is a few instances of the behind the beat playing that is so prominent in Stella by Starlight, (bars 1, 3 [see ex.69], 24) and one of playing ahead of the beat (bar 104 [see ex.70]). These again of course, create a sense of rhythmic elasticity, though it seems that with Jarrett (in this case at least), the swing feel of Stella is far

more conducive to this kind of approach than the straight eighths feel that is found here. The third is the small number of irregular groupings of notes that are found mainly in the last part of the solo (bars 94, 100 [see ex.71], 104) and which create the impression of brief departures from the

ground beat.

Harmony

Again, the chord changes here essentially follow those in the melody section, but with a number of variations. The bass’s role is again, both functional and melodic, but in this case the melodic figures tend to utilize the fifth more than any1hing else, as this is more in keeping with the traditional approach to pieces with straight eighths and Latin feels. A couple of the harmonic sections are treated quite loosely, and the first of these is the section which is found in the second bar of each four bar C minor sequence. Here, Jarrett often plays just G 7, but Peacock frequently plays D, G, and occasionally this results in a momentary conflict (e.g. bar

24 [see ex.72]).

The second is the descending chromatic sequence found in bar 22 of the

structure. In the first two choruses (bars 22 and 58), the piano plays all C minor but the bass plays C, B. Bb, Eb, and in the third (bar 94), the piano outlines the changes whereas the bass plays more of a C minor figure (see ex.73). Obviously, these variations contribute to a sense of harmonic freedom.

The most sustained and substantial variations however, occur from bars 66 to 72 (see ex.74). In bar 66, we see an Eb 7 alt chord played under a D 7 line (harmonic suspension), followed in 67 by a Bb minor chord over a B bass note (harmonic anticipation), and then in 68 we see E min. 7, A 7 in place of Eb 7 (a tri-tone substitution). In bar 69 we not only see a D bass note in place of the usual Ab, but also the beginning of an interesting three bar harmonic episodes. Here, (at the very end of the bar) Jarrett plays a root position F major 7 chord in the left hand, anticipating the next bar (which would normally be F minor 7, Bb7), but really functioning as a G7sus chord.

Peacock immediately responds with a G pedal figure at bar 70 (which he maintains throughout), and Jarrett shifts the left-hand chords down chromatically whilst playing right-hand lines that essentially outline G7. All of this creates considerable drama, as it bypasses the resolution to the

relative major in favor of a dominant pedal. (It is also interesting to note that at bars 106 and 107 the resolution to the relative major is again bypassed in favour of a II VI progression in C minor.)

Another variation can be found at bars 43 and 44 (see ex.75), where the bass plays an Ab figure at bar 43 (non-specific chord quality) in place of the usual D, and then at 44 plays D, G, rather than just G. The piano line at 43 suggests Ab minor for beats 1, 2, and 3, and G7 for beat 4 (there is no left hand in this bar), and then at bar 44 it outlines 07, G7.

The above examples demonstrate very well the level of spontaneity and empathy that is present between the players. Author Geoff Dyer made the following comment about the trio – ” … while listening to the trio, it is often impossible to tell who is leading and who is following, who is

initiating and who is responding.”

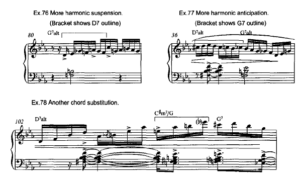

Another example of harmonic suspension can be found at bars 80 (a 07 chord is outlined over a

G7 [see ex.76]).

More examples of harmonic anticipation can be seen at bars 36 (see elS.77) and 108 (where the line is all G7, but the chords are 07, G7). Another example of chord substitution can be found on beat 3 of bar 1 02, where a C# minor harmony is played in place of G 7 (see ex. 78).

The variations here, of course, create tension, add color, and contribute to a sense of harmonic sophistication and freedom.

Melody

Not surprisingly, a lyrical quality again pervades here, but the overall melodic character is quite different to Stella by Starlight. The minor key and different rhythmic feel of the piece (particularly the double time section) obviously contribute to this, but it is also testament to Jarrett’s range and ability to improvise fresh lines each time he plays. lan Carr, talking about one of Jarrett’s solo tracks, compared his fast runs with those of Art Tatum- “… whereas the latter (Tatum) often performed the fast runs which were his stock-in-trade and part of his habitual repertoire, Jarrett seems to be actually conceiving and playing new lines at this

amazing speed and intensity.”

The organizational approach tends to be based upon scalar shapes. More than anything else, but there is a large variety of these (a lot of which utilize chromaticism), and arpeggiated figures feature throughout. The previously mentioned allusions to the original melody can be found in bars 5 and 6 (see ex.79), 10, 26, and 31-33, and once more, grace notes can be

seen in the last bar of the solo break, and bars 8 (see ex.80), 9, 12, etc.

Before the aspect of chromaticism is looked at, the general diatonic shapes will be described, and again, these range from scale passages (bars 3 [see ex.81], 49 and 50 [beats 4 and 1 respectively], 74 etc.), to scalar-type figures (bars 53 [see ex.82], 67, 78 etc.), to more purely melodic shapes (bars 2 [see ex.83], 7 [beats 3 and 4], 31, 38 etc.), and to melodic shapes which feature large intervals (last bar of solo break [see ex.84], bars 1, 22, 46, 70, etc.).

The use of chromaticism will be described as before:-

The use of chromatic notes as,

1) Components of chromatic scale passages (bars 42 [last 2 semi quavers to beat 2 of 43 – see ex.85 ], 91[first 6 semi quavers, 94 [beat 2]etc. ).

2) Passing tones (bars 15 [see ex.86], 28 [beat 1, 2nd semi quaver], 36 [beat 3, last semi quaver], 56 [beat 2, 2nd semi quaver] etc.).

3) Approach tones (bars 7 [see ex.87], 27 [last semi quaver], 28 [beat 2, last semi quaver], 52 [first semi quaver] etc.).

4) Dissonant tones which fall on the main beats and then resolve (bars 8 [beat 3], 16 [see ex.88], 28 [beat 3, 3rd semi quaver], 41 [B natural], etc.).

5) Upper and or lower neighbour tones (bars 36 [see ex.89], 46 [beat 3], 54 [beat 3]).

6) Components of general or universal melodic shapes (“1” – bar 55; “2” – bars 43, 59 [beat 4, slightly modified], 68 [beat 3]; “3” – bar 93; “4” – bars 36, 56 [beat 3], 68 [beat1], 90 [beat 3], 1 08 [beat 2 – These differ slightly from the original model, but have the same shape]; “5” – bars 43, 56 [beat 4], 69 [beat 1], 103 [beat 3 – These tend to differ a little from one another, but all have similar shapes] – For examples see ex. go).

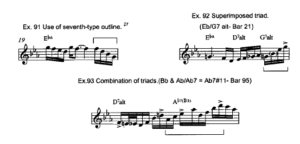

The arpeggiated figures tend to utilize either traditional seventh-type formations (bars 18-20 [see ex.91], 59 [beat 2], 71 [beat 4], 89, 90 etc.), superimposed triads (bar 21 [see ex.92], bar 39 [G/C minor= C min maj.9], bar 66 [Bb/07 = 07alt.] etc.), or combinations of triads (bar 95 [see ex.93], bar 102 [Bb & Ab minor/07 = 07alt.,013b5b9].). Obviously, these provide contrast to the prevailing scalar approach.

The role of the left hand

In general the left hand is used throughout, although there are two sections where it is absent for a number of bars {60-63 and 72-78), and in the second of these, it contributes to the leveling out that occurs at the beginning of the third chorus. This connection actually typifies the overall role here, as the left hand tends to be an integral part of the changes in intensity.

In the first chorus, there are many sustained chords along with shorter ones, and they tend to be both on and off the beat, this mirroring the steady build of the solo (see ex.94). In the second and third choruses (which feature the double time feel), the chords on the whole tend to become shorter and more syncopated, and are particularly active in supporting the increases in intensity.

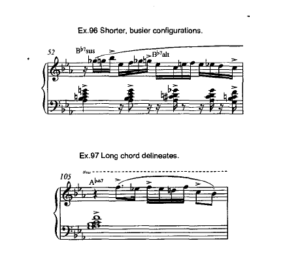

This often involves the playing of longer chords which are heavily accented and off the beat (bars 48-51(see ex.95), 65, 69,70 [see Harmony] etc.) as well as shorter, busier configurations (bars 52 (see ex.96), 56, 66, 68 etc. The long chord at bar 105 delineates the beginning of the brief wind down section (see ex.97).

Closing melody section

The character here contrasts very much with the preceding bass solo section (which maintains the aforementioned double time feel), and is played essentially with a half-time feel. This is achieved primarily by Jarrett’s use of a more sustained, minim based left-hand accompaniment, and the pattern that DeJohnette plays on the ride cymbal.

Again, we see the retention of enough elements from the opening melody section (essentially the same chord changes, a similar approach to the melody, a certain sparseness, occasional hints of the same rhythmic ploys) to ensure thematic continuity, but also enough differences (the previously mentioned half time feel, subtle harmonic variations, a little more of the original

melody, less rhythmic tension) to give it a change of character, and make it clear to the listener that a musical journey has taken place. Once more, Jarrett’s cadenza begins at the final resolution point (bar 35).

The cadenza (see ex.98)

This is 37 bars long, and lasts for just under a minute. Its basic structure is fairly simple, as it essentially utilizes one melodic motif throughout, and uses a harmonic progression which descends chromatically from the dominant of the relative major, Bb, to the tonic, C minor. (Note that this progression ties in with the chromatic progressions that occur in the introduction.)

The motif is derived from the melody notes that originally occur in bar 34 (see ex.99), and these, of course, are derived from the main theme of the piece. As it begins, Jarrett changes into 3/4 and doubles the speed (the quavers of the closing melody section then become crotchets), and much like the introduction, it is played in tempo throughout (except for a brief ritardando at the end).

However, the rhythm of the melody in this case is a constant stream of crotchets, and potential monotony is avoided by the use of (again) varied time signatures (the aforementioned 3/4 combined with many bars of 4/4 and 5/4), changes to the melody notes (which of course reflect the changing harmonies), and the use of counter melodies in the tenor part. The tonal center of C minor is established by the reiteration of the tonic in the last 10 bars, and the movement of the counter melody, which circles around the fifth until the final resolution.

Jarrett’s statement here functions very well in providing a thematically based conclusion to the piece, and does so once more with just the right balance of repetition and variety.

Overview and Summary

The introduction, again of course, functions as a prelude, but because in this case the melody of the song is not used, there is very much a sense of it being a piece in itself. This compositional quality is enhanced by the consistent pulse, which leaves little room for reflection. Its shape tends to be that of a gradual build towards a climax and then a winding down, which clearly signifies a delineation between sections, and of course sets the mood for the opening melody section.

This section obviously introduces the melody of the piece and the ensemble part, but also has its own profile, which is most apparent in the first half of the B section (where a rhythmic displacement occurs). The first eight bars of the C section (where there is a rhythmic block chord passage), and then in the last four bars where there is a clear breathing space between sections.

The piano solo once more functions as a development section. And in the first chorus it steadily works towards the second, where the change to the double time feel, though creating a different mood, feels like a natural progression. Again, the second and third choruses continue the development. Essentially, by increasing the levels of intensity via plateaus until a climax is reached. The wind down following the climax of course serves to delineate the piano solo from the bass solo, but in this case it is only four bars long. And the intensity level is still relatively high.

The closing melody section, once more, functions as the final part of the development by the ensemble, and again (as previously mentioned) makes it apparent that a musical journey has occurred through another change in character. This character changes immediately once Jarrett signifies his intention to begin the cadenza, and prompts the band to drop out. The

cadenza then functions as a coda that has obvious thematic content, similarities to the introduction, and is again, of course, played by the piano alone.

The overall impression one gets from this performance is similar to that of the previous piece. There is a sense of it being a musical story which is high on passion, very flowing, and definitely “in the moment” at all times. Again, this story is made up of many musical episodes which are underpinned by a strong sense of form and structure, but the level of

spontaneity makes it a different story to Stella by Starlight, and the straight eighths feel and inherent differences in the introductions (of course) contribute to this.

Jazz shee music download here.

Keith Jarrett – Tokyo Solo 2002 Encores

Browse in the Library:

Or browse in the categories menus & download the Library Catalog PDF: