Come join us now, and enjoy playing your beloved music and browse through great scores of every level and styles!

Can’t find the songbook you’re looking for? Please, email us at: sheetmusiclibrarypdf@gmail.com We’d like to help you!

Aram Khachaturian (1903-1978): A Retrospective

Best Sheet Music download from our Library.

Of the three stalwart Soviet composers who had achieved international fame during the reign of Josef Stalin, namely Sergey Prokofiev, Dmitri Shostakovich, and Aram Khachaturian, it was the latter who most consistently exemplified the tenets of Soviet Realism.

As 2018 marks the fortieth anniversary of his passing, it is a fortuitous time to reflect on his music and take note of how it may be assessed from the vantage point of hindsight. The stunning international success of a single number, the “Sabre Dance,” from his ballet, Gayane (1942), might have marked Khachaturian as a one-hit marvel after it was popularized in a uniquely “low-brow” American manner.

It served, e.g., as the accompaniment to plate-spinning entertainers on the Ed Sullivan Show on CBS-TV. The complete ballet, however, and the three suites extracted from it, achieved, along with other works by the Armenian musician, acclaim from the political gurus on both sides of the Iron Curtain.

Please, subscribe to our Library.

If you are already a subscriber, please, check our NEW SCORES’ page every month for new sheet music. THANK YOU!

The works of the student years were considerable (more than fifty) and already suggest the individual styles with which he later became associated.

Khachaturianʼs compositions encompass such genres as the symphony, the concerto, film scores, incidental music to plays, band music, vocal and choral compositions (including such patriotic efforts as Poem on Stalin and Ballad about the Motherland), and, what might be regarded as a sequel to the three earlier concertos for piano, violin, and cello, viz, the Concerto-Rhapsody for violin and orchestra (1961), the Concerto-Rhapsody for cello and orchestra (1963), and the Concerto-Rhapsody for piano and orchestra (1968).

His final works moved in a somewhat austere direction, certainly unlike the full-blown soloorchestral music with which he is associated; they feature the Sonata-fantaziya for solo cello (1974), the Sonatamonolog for solo violin (1975), and the Sonata-pesnya for solo viola (1976).

Although he was widely honored by the Soviet regime, one aspect of which was the incorporation of a state policy known as Socialist Realism in 1932 under the Georgian dictator, Josef Stalin, Khachaturian ran afoul of the so-called Zhdanov Doctrine, a cultural decree which, supportive of Soviet Realism, promoted the idea that the common man was at the center of Soviet life and, consequently, his humanity should be the central focus of all artistic works.

This study treats the stylistic propensities of Aram Khachaturian from his student works to his final creations, examines the political influences of his country on his life and esthetic sensibilities (he was a true believer in Communist ideology), and provides evidence that, as the post-Zhdanov years rolled along, and as his works, with their fascinating mix of Eastern and Western tendencies, came to be seen as worthy of renewed interest, the composer of the once-infamous “Sabre Dance” is experiencing a musical reawakening.

As a result, a series of posthumous honors and distinctions have been bestowed upon him, embracing more fully than ever the admixture of his Armenian heritage, his Georgian upbringing and early schooling, and his Soviet-Russian musical training and cultural life.

Browse in the Library:

Or browse in the categories menus & download the Library Catalog PDF:

Introduction

When in the Spring of 1978 Aram Ilʼyich Khachaturian left his earthly existence (his grave is in the Komitas Pantheon in Yerevan, Armenia), the world was witness to a unique musico-political spectacle, viz. a composerʼs obituary written by Leonid Ilʼyich Brezhnev, Chairman of the Presidium of the Supreme Soviet and General Secretary of the Communist Party of the Soviet Union, and the pallbearers at his funeral including Aleksey Kosygin, Premier of the Soviet Union.

This intermingling of the worlds of politics and music, a simmering stew that characterized Soviet cultural life, played a central role in the personal and professional life of Khachaturian, who was born to Armenian parents on 6 June 1903 in the Georgian city of Kodjori, a suburb of Tiflis (now known as Tbilisi). Along with such other musical titans as Dmitri Shostakovich and Sergey Prokofiev, he was both lauded and condemned by Soviet officialdom according to the direction in which the political winds were blowing at any given time.

Early Years

The youngest of four sons (a daughter died at the age of 1), Khachaturian became acquainted early on with Armenian and Azerbaijanian folk songs as a consequence of his family background. To this tradition, he added a general flavoring of the rich and diverse folk heritage of the Caucasus and mixed these features into the more traditional academic styles which he encountered during his formal studies with Mikhail Gnessin and Nikolai Miaskovsky in Moscow.

It was, indeed, his brother Suren who, in 1921, brought him to the Russian capital, where he entered the Biology Department at Moscow University while studying concurrently at the Gnessin Music School.

Despite his limited youthful forays into the arcane world of music (he was self-taughton the piano and played tenor horn in the band at the Tiflis Commercial School), he undertook a serious approach to the study of the cello and, in 1923,entered Gnessinʼs composition class.

As his mentor, a Jew, was fascinated bythe music of his religious heritage and combined this with the so-calledRussian-Oriental style acquired through his training with Liadov, Glazunov,and Rimsky-Korsakov, it is not surprising that the Georgian youthʼs earliest efforts reflected an admixture of the styles promulgated by the masters cited herein.

The Poem in C-sharp minor of 1927 (Example 1), as with many of the composerʼs works (the Collected Works are published by State Publishers”Muzyka” in Moscow), is notable for its frequent changes of meter, tonality, dynamics, and mood, aided and abetted by a free use of rubato; it received its initial publication by the Music Section of the Armenian Gosizdat, Yerevan in Dedicated to his friend, Yuri Sukharevsky, it made a deep impression on the composer and pianist, Eduard Mirzoyan:

When I began learning Khachaturianʼs Poem I was at once overwhelmed by the wealth of unexpected and exciting impressions, actually a perfectly new musical world, which it opened before me. This music struck me as faintly familiar and at the same time astonishingly and refreshingly novel.

This novelty lay in the composerʼs approach to the traditional musical material so well known to us, in the lush and highly original harmonies, riotous colors and imaginatively varied piano writing which seemed in itself pronouncedly national. It gave me special pleasure to play Khachaturianʼs Poem and I preserved it in my piano repertoire for many years.

In 1929, a dozen years after the Bolshevik Revolution, Khachaturian followed his teacher to the Moscow Conservatory, studied with him for another year, and then pursued advanced studies with Miaskovsky and Vasilenko. The years spent as a student at this venerable institution, which extended to 1936, saw the creation of more than fifty compositions; these included perhaps his best known work for solo piano, the Toccata in E-flat minor, composed in 1932 under the tutelage of Miaskovsky and first published in 1938 by the Muzgiz. Rodion Shchedrin said of it:

Khachaturianʼs Toccata, a full-blooded, vividly emotional piece, is constantly performed on the concert stage, at palaces of culture, workersʼ clubs and over the air. There hardly is a professional pianist who does not know it by heart, and few amateurs who do not cherish the ambition of being able to play it some time.

Originally the opening movement of a Suite, the other movements of which are titled “Waltz-Capriccio” and “Dance,” it is in a tripartite structure. The work features rapidly repeated notes as would be anticipated in a “touch piece,” and it contains other features associated with its composer, such as ostinati comprised of conjoined alternating fifths, perfect and diminished, and a luxuriant B section with melismatic chromatic passages suggestive of eastern exoticism influenced by the Asiatic Republics of the former Soviet Union (Example 2). As with the Poem, it also contains elements of bimodality and bitonality and chords with superimposed seconds and ninths.

While Tiflisʼs gift to the musical world was experiencing the birth pangs of the composer, it is instructive to note the conflicting currents in which the Soviet artist was enmeshed in the decade following the Revolution of 1917. A modernist movement, exemplified by such figures as Léon Theremin (1896-1993), Alexander Mosolov (1900-1973), and Vladimir Deshevov (1889-1955) was heralded in the pamphlet, October and New Music, published by the Leningrad Association of Contemporary Music in 1927, the period of Khachaturianʼs Poem in C-sharp minor:

What is closer to the proletariat, the pessimism of Tchaikovsky and the false heroics of Beethoven, a century out of date, or the precise rhythms and excitement of Deshevovʼs Rails? Proletarian masses, for whom machine oil is motherʼs milk, have a right to demand music consonant with our epoch, not the music of the bourgeois salon which belongs to the era of the horse and buggy and of Stephensonʼs early locomotive.

While Deshevovʼs homage to the workerʼs paradise is scored for solo piano, Mosolovʼs ballet, The Factory, a movement of which is known in the West as The Iron Foundry, includes in the score metal sheets to be shaken to simulate the sound of a factory at work.

Among his other innovative approaches are songs composed to texts drawn from newspaper ads. Be it noted also that this “new music” movement included the establishment in Leningrad of the Society of Quarter-Tone Music by George Rimsky-Korsakov, grandson of the composer of Scheherazade, and the formation of Tritone, a music publishing firm whose name conveyed the character of the music it was prone to disseminate to the public, The use of quarter tones found support outside the Soviet Union; Blochʼs Piano Quintet No. 1 and From Jewish Life for cello and piano, and Coplandʼs piano trio Vitebsk are notable examples.

If the modernist enterprise was a thesis to be foisted upon a somewhat innocent public, an antithesis, in the form of an organization known as the Russian Association of Proletarian Musicians (RAPM), was organized in 1924, the year in which George Gershwinʼs Rhapsody in Blue was introduced at Aeolian Hall in New York. It declared boldly that,

The brilliant development of musical culture of the ruling classes was made possible by their possession of material and technical tools of musical production. As a ruling class, the bourgeoisie exerts great influence upon all strata of the population, systematically poisoning the workerʼs mind. In the field of music, this process follows the lines of religious and petty-bourgeois aesthetics, and recently, the erotic dance music of contemporary capitalistic cities (fox trot, jazz, etc.).

The RAPM was virulently opposed to mechanistic music, and, instead, advocated a traditional approach to musical creativity; indeed, it praised the music of Beethoven and, among the late nineteenth-century Russian School, gave its blessing to the nationalists, Mussorgsky in particular.

As it gained strength in cultural and political circles, the modernist school came under increasingly negative scrutiny, the result of which was that its musical adherents found it in their best interests to repudiate what they had wrought and to turn to a more politically correct approach to their art. Mosolov, for example, traveled to Turkestan, collected folk songs, and incorporated them mundanely in such works as his Turkmenian Suite. The likes of The Factory were consigned to an honored place in musical Hell.

By 1932, a new “ism,” Socialist Realism, was imposed upon the proletariat by the then dictator of the Soviet State, the Georgian-born Josef Stalin, and ratified by the Congress of 1934. Its essential components were that art works (a) reflect relevance to the working class and that they be understandable to that class, (b) that they aspire to represent the every-day life of the people, (c) that they be definable as realistic in the representational sense of that term, and (d) that they reflect the principles of the Soviet State and the Communist Party.

Khachaturian, among the major composers of the Stalinist era, was an enthusiastic supporter of Communistic ideals, including expansion of ideology.

His early Trio of 1932, a student work for piano, violin, and clarinet, reflects the aesthetics of the RAPM in its formal design and the folkloric features promoted by Stalin. Elements drawn from ashug music, such as melismatic melodic phrases, Eastern dance rhythms, modal flavoring, and, in the final movement, an Uzbeki folksong, are combined with European features, including French impressionism.

As in other works, Khachaturian employs modern instruments to imitate the sounds of folk instruments, in this instance the dohl, a two-headed drum which can be played with either the hands or sticks; the kamancha, a bowed stringed instrument of Persian origin and an ancestor of the modern violin, common in the classical music of Iran and Azerbaijan; and the duduk, a double-reed instrument widelyused in Armenian folk music.

The Composer Establishes Himself

Symphony No. 1, dating from 1934, was composed to commemorate the fifteenth anniversary of the establishment of Soviet power in Armenia. In this important foray into the genre that has been seen for generations as the musical venue where one sinks or swims as a creative artist, the musician altered the traditional form of the first movement which, as with other works of this student period, meld together eastern folkloric materials with the compositional expectations of the academy.

The formal novelty centers about issues of thematic development in the first movement. Materials drawn from an introductory Prologue form the basis for the traditional bi-thematic approach to sonata-allegro form, except that these themes are elaborated upon developmentally in the

expository section and then again even more so in the recapitulation section. The primary themes maintain their individual identifying features despite the ongoing elaborations, but their pure elemental presentation at the beginning of the movement returns to the closing epilogue.

The exotic element is noted by Margarita Rukhyan, the Armenian music critic: “The contest of two ashugs, voicing two philosophies, two temperaments, contains the nucleus of the development of the elaboration which acquires an original trend thanks to a third party—the people, who judge this contest.”6 A true development section in the formal sense is not part of the equation. The slow second movement is in a typical tripartite structure, with allusions to folk dance traditions of Eurasia, while the third movement, as in many of the masterʼs large-scale symphonic works, is

notable for its rapid dance rhythms and its cyclical return of materials from the opening movement.

Although some student works of the ʼ30s, such as the Poem and Toccata cited earlier, reflect the modernist tendencies later decried by the new order, others, such as the various dances for wind orchestra (the two dances based on Uzbek folk songs and the two dances based on Armenian folk songs were written for the fifteenth anniversary of the Red Army), the Trio for clarinet, violin, and piano of 1932, the Dance Suite in five movements of 1933 (the last movement, composed a few years later and added to the suite, is a Georgian Lezghinka), and the Piano Concerto in D-flat major of 1936, adhere closely to the Party line as do those of the 1940s and beyond.

The Piano Concerto, first introduced to the public by Soviet pianist Lev Oborin with the Moscow Philharmonic under the direction of Lev Steinberg at Sokolniki Park on 12 July 1937, was promoted and recorded in the West by such artists as William Kapell, Moura Lympany, and Oscar Levant. Among its notable features are bravura cadenzas in the Development of the first movement, cyclical thematic usage (e.g., the opening theme is recalled at the close of the work), thematic interconnection among the three movements (e.g. the principal themes share the commonality of major-minor thirds), tonal clusters in abundance (a feature common to the composerʼs works in general), and, in the second movement, the inclusion of a prominent role for the flexatone7 (Example 3).

The main theme of this movement is based upon the Caucasian folk song, “My lover.” Yet, its specific origin seems to have eluded the musicanti. The composer explained his intent truly:

By taking this melody as the basis for the central theme of the Piano Concerto obviously ran the risk of the critics tearing me to pieces when they learned the source of the music. But I departed so far from the original, changing its content and character so radically, that even Georgian and Armenian musicians could not detect its folk origin.

As in each of Khachaturianʼs concerted works, the solo part, which enters after a short orchestral introduction, is marked by virtuosity of the nineteenth century order, and, while creating a challenge for the soloist, it is a feature which has assured an audience appeal that is not often encountered to this degree in similar works by the more avant-garde composers of the twentieth century.

During the 1940s, Khachaturian produced a plethora of diverse works, among which are three-movement concerti for the violin (also in a version forflute) and cello. Formally, they follow the pattern of the Piano Concerto, thus material from the first movement finds its way into the finale, thematic materials are expanded after their initial appearance, cadenzas are tours de force (Example 4), and folkloric elements abound. Artists of the first rank, David Oistrakh for the Violin Concerto, and Svyatoslav Knushevitsky for the Cello Concerto, introduced these works as well. The composerʼs collegiality with regard to his chosen soloists is exemplified by Oistrakhʼs comments:

… I came to know him quite well while the Violin Concerto was being written. I remember that summer day in 1940 when he first played the Violin Concerto, which he had just finished. He was so totally immersed in it that he went immediately to the piano. The stirring rhythms, characteristic turns of national folklore, and sweeping melodic themes captivated me at once. He played with tremendous enthusiasm. One could still feel in his playing that artistic fire with which he had created the music. Sincere and original, replete with melodic beauty and folk colors, it seemed to sparkle. All these traits which the public still enjoys in the Concerto made an unforgettable impression at the time. It was clear that a vivid composition had been born, destined to live long on the concert stage. And my violin was to launch it on its career.

Six years later, the Cello Concerto made its appearance, representing the first major work following the close of World War II. The Introduction to the first movement is much longer than it was in the previous two concerti, but the general format is similar. Knushevitsky, the works dedicatee, was accompanied by the Moscow State Symphony under the direction of Alexander Gauk on 30 October 1946. The elegiac and at times dolorous atmosphere of this work has resulted in an audience and critical reception less accepting than that which greeted the previous concerti. The reduction in bravura in favor of more contemplation suggests that the public prefers old-fashioned virtuosity in their concerted works.

Other notable creations of this period include incidental music to plays, the best-known score of which is Masquerade (play by Mikhail Lermontov). A five-movement suite, extracted by the composer in 1944, consists of the following movements: “Waltz,” “Nocturne,” “Mazurka,” “Romance,” and “Galop.” There are also many patriotic and nationalistic songs, and the Symphony No. 2 in E minor (Symphony with Bells) and Symphony No. 3 in one movement, also known as Symphony-Poem, a work that is outsized for its time (1947) among Soviet symphonic creations; the score includes organ and fifteen solo trumpets.

Khachaturian had adjusted his creative bent to conform to the requirements for a successful professional life by composing as officialdom decreed while being true to his personal artistic creed. The Second Symphony, a “war symphony” owing to its creation in 1943, bears some resemblance to the more somber utterances of Shostakovich, notably the latterʼs Symphony No. 7 (“Leningrad”). It is referred to as the “Bell” symphony in Russia due to its descending motif, F-D-D-B played initially by bells, piano and winds, a motto which recurs throughout the work. Notable also is the darkly hued chorale in the violas, a theme which may well be intended as a reference to a people enduring the hardships of war. It returns to the close of the symphony along with the “bell” motto.

A traditional scherzo with trio occupies the second movement slot, but it is more than a jocular romp as it encompasses the diminished fifth of the first movementʼs motto in muted horns, creating thereby a fearful reference to its earlier appearance. The third movement, essentially a funereal march, refers again to the opening motto but also includes the Dies irae. The final movement, introduced by a fanfare, recalls materials from the previous movements, thus bringing organic unity to the four-movement work as a whole.

International Fame and Political Realities

The ballet Happiness, inspired by a visit, in 1939, to Yerevan, dealt with the common people by way of featuring as primary characters frontier guards and collective farmworkers. It was the precursor to Khachaturianʼs politically-themedballet, Gayane, composed in 1942 and revised in both 1952 and 1957. Originally athree-act work, it evolved into a 4-act creation, with a deeper penetration of the inner selves of the principal characters, and increased thematic development.

The story line, which centers about life and love on a collective cotton farm, features a diversity of ethnic dances owing to Konstantin Derzhavinʼs libretto which emphasizes the farmʼs culturally varied inhabitants. The dances themselves are introduced as a natural aspect of the lives of the people rather than, as in traditional classical ballet, set pieces in which all the dancers are dressed in the expected costumes and in which the dances tend to be set as divertissements, à la salon as it were. Of the dances that have found their way into several suites and other “highlights” settings for orchestra, the “Lezghink(a),” a fast mountain dancein the context of this work, is generally thought of as a slow dance a ssociated with Muslim peoples who lived in Persia; it is often performed as a distinct showpiece quite apart from its balletic association.

Without doubt, the most popular of the dances is the infamous “Sabre Dance,” which has taken on a life of its own, even more so than has the Lezghinka. The bristling minor seconds in the left-hand part of the piano score sharpen the thrust of the piece (Example 5). The composer has written about its late arrival into the score:

My Sabre Dance came into being quite by accident. One day while rehearsals were in progress, the director invited me to the theater and said that he wanted to have one more dance in the final act. I considered the ballet completed and declined to add anything to the music. On coming home, however, I sat at the piano and began thinking about what kind of dance would be suitable. I visualized a quick and warlike dance. My hands struck a chord as if obeying an inner urge, and I repeated it as an ostinato; then I felt that a sharp shift was necessary and added the leading note in the upper part. Well, well, thatʼs something like it! … Letʼs play it in another key … Got it! Now for contrast. I thought of the lyrical dance with a flowing melody in Scene Three. I added this theme (played by a saxophone) to the warlike material, and after that repeated the beginning, in a new guise, of course. I started work on the piece at three p.m. and it was ready by two a.m. the next day. At eleven oʼclock the orchestra was playing the dance, by the evening it had been staged – and the dress rehearsal took place the day after.

In the West, the sabres have been rattling far beyond the original intent. The dance, e.g., accompanied plate spinners on the Ed Sullivan Show, a one-time staple of Sunday night televiewing on the CBS network, and it has been variegated to meet the needs of diverse performers such as the three Andrews Sisters; Wolf Hoffmann, the heavy metal guitarist; and UK Subs, the British rock band. Its use in circuses to accompany acrobats and animal acts has caused it to be described by the pejorative adjective “notorious.”

Its artistic values were also questioned by arbiters of good taste when it found its way to Late Night with Conan OʼBrien where it accompanied the Masturbating Bear when this regularly featured character regularly masturbated on stage. But be it noted that a more “serious” usage was found for it on the TV news commentary program, Countdown, with Keith Olbermann on MSNBC-TV where, from 2003-2007, it was heard on the segment known as Oddball, so named for the off-beat stories featured thereon. Khachaturian wrote this showstopper in one evening; it was not intended to be part of Gayaneh. The colloquialism, “Go figure!,” comes to mind here.

The incidental music for Lermontovʼs play, Masquerade, and the suite drawn from it in 1944, has become part of the established Khachaturian canon. A previous production with music by Alexander Glazunov (1865-1936) was viewed by the composer in 1938; oddly, the “Waltz-Fantasy” by Mikhail Glinka (1804- 1857) was inserted in the place where a waltz was indicated in the play as per the instructions of Glazunov. Khachaturian, who surmised that the earlier composer had difficulty producing the requisite dance piece here, found that he, too, was stymied to find the proper stylistic atmosphere for his effort.

His teacher, Miaskovsky, presented him with a collection of waltz pieces that predated the era of Glinka, but these did not satisfy him. The need for a waltz that could somehow convey the mixture of sadness and happiness came to him, according to his own recollection, while he was sitting for a portrait of himself by Evgeni Pasternak:

One day while posing I suddenly heard a theme in my head which became the second theme of my future waltz. I doubt if I can explain where it came from. But I am certain that, had it not been for the strenuous search of the past weeks there would have been no such discovery. The theme was like a

magic link, allowing me to pull out the whole chain. The rest of the waltz came to me easily, with no trouble at all.

The “Nocturne,” “Mazurka,” “Romance,” and “Galop” are the accessible andmemorable other movements which follow the waltz (Example 6).

Colorful orchestration and, in this instance, dances contrasted with slower, lyrical sections appropriate to a masked ball, aristocratic in nature, rather than to a cotton farm peopled by the peasantry, signify a composer possessed of supreme craftsmanship. The story line and music are unified artistically and expeditiously.

Pianists have welcomed a version for solo piano by Alexander Doloukhanian approved by Khachaturian.12 Credit for the first performance of the suite in America goes to the Santa Monica Symphony Orchestra, which performed it on 7 May, 1946 under the direction of Jacques Rachmilovich. The composer has arranged the “Nocturne” for violin and piano.

Given his prominence in the Composerʼs Union and the esteem in which he was held by the Stateʼs arbiters of matters cultural, Khachaturian, who had joined the Communist Party of the Soviet Union in 1943 and had been a recipient of such honors as the Order of Lenin and the Stalin Prize, could not have predicted his ungraceful fall from grace as the recipient of collateral damage in an attack launched by the Central Committee of the All-Union Communist Party on 10 February 1948.

Although Vano Muradeli (1908-1970) and his opera Great Friendship, premiered a few months before this outburst, on 7 November 1947, were the central targets, other composers included in this sweeping denunciation included such very diverse figures as Shostakovitch, Prokofiev, Miaskovsky, Kabalevsky, Shebalin, and Khachaturian. The “catch-all” term “formalism” was employed to reference various modern tendencies, including atonalism, dodecophony, cluster chords, and jazz wherever these were applicable.

Khachaturianʼs Symphony No. 3, composed to honor the thirtieth anniversary of the October Revolution, and premiered on 13 December, 1947 by the Leningrad Philharmonic Orchestra under the direction of Evgeny Mravinsky, was ostensibly the work which merited his inclusion among the “formalists.”

Oddly, it received a glowing review from journalist G. Lvov in the Information Bulletin of the Russian Embassy in Washington prior to its completion;14 odder still was Khachaturianʼs letter to this publication dated 28 February 1948 in which he chastises Lvov for his laudatory comments and, with his metaphorical tail between his legs, agrees with the Central Committeeʼs concurrence with the so-called Zhdanov Doctrine, developed in 1946 when Andrei Zhdanov (1896-1948)15 was secretary of the Committee.

He goes on to state that, although this action may be seen by commentators abroad (the West) as a purge, he asks the following question with its answer implicit in the question itself: “How can there be any question of “purging” when the Central Committee, while pointing out very justly the errors into which a number of Soviet composers have fallen, indicates the path which should lead Soviet musical culture to the creation of work of really high quality and finish, such as may be comprehensible to all people, and also offers full opportunity to the composers named in the decision to participate in this work?”

Such a mea culpa is quite bizarre considering that, of all the composers indicted, Khachaturian was, and is still, seen by objective observers as the least objectionable figure with respect to falling into the bourgeois trap known as formalism. There is a touch of irony in the fact that in 1939 Khachaturian received the Order of Lenin for distinguished service to the State by way of the music he penned for the ballet Happiness, and, during the 1940s, he was rewarded with the Stalin Prize17 for his Violin Concerto (1941–second class), Gayaneh ballet (1943), and Symphony No. 2 (1946), a prize whose purpose was to recognize achievements which brought honor to the Soviet Union and/or socialism.

Of smaller-scaled creative endeavors which preceded the 1948 ruckus, an exemplar of an effort that also converged with the prevailing views of officialdom is the National Anthem of the Armenian Soviet Socialist Republic,18 for which Khachaturian composed the music (Example 7) in 1944 to lyrics by Armenak Sarkisyan (1901-1984), better known by his pseudonym “Sarmen.” The chorus sings such texts as “Glorious be, glorious be, our Soviet Armenia!” and, at the close, salutes Russia, the Communist Party, and Communism; the powerful music, chordal, hymn-like, and dynamically loud, would have delighted commissars, sycophants, and the public at large.

Regarding the Symphony No. 3, its irregularities were not cited by political critics, viz. the fifteen trumpets in addition to the three regular trumpets in the orchestra, the powerful organ part, and the non-programmatic single movement that justifies the appellation, symphony-poem. It was the composerʼs intent to capture the ebullient spirit that he envisioned had enveloped the Soviet people in light of the country victory in World War II and its increasingly powerful place in world affairs.

The sheer volume of the work as a whole, and the ceremonial sound created by the massive array of trumpets plus the organ, disconnected from its customary association with matters liturgical and now identified with a greater societal role, were intended to induce a swelling of national pride.

As with others among “the condemned,” Khachaturian had written patriotic and nationalistic music during his early years, and continued to produce works glorifying the State and its primary leaders, such as his (Funeral) Ode in Memory of Vladimir Ilyʼich Lenin19 drawn from the film score for “Lenin,” a work first performed on 26 December, 1948, the score for the film “Battle of Stalingrad,” in 1949,20 from which an eight-movement Suite was constructed, and many others in subsequent years, including March of the Soviet Militia in 1973 and Triumphal Fanfares for 8 trumpets and 2 drums “for the thirtieth anniversary of victory in the

Great Patriotic War” in 1975.

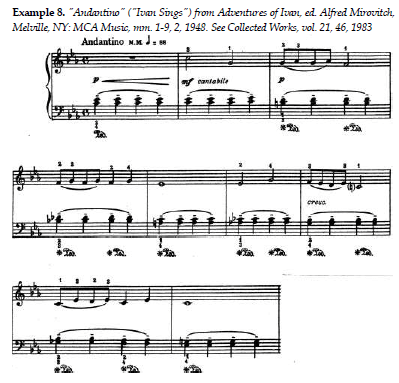

Music for children, also an ideal fostered by state musical overseers, did not escape Khachaturianʼs purview; indeed, in 1947 most of his first Childrenʼs Album for piano was composed. A year later it was published in the west under the title Adventures of Ivan with eight of the original ten pieces intact. The editor, Alfred Mirovitch, provides helpful introductory remarks:

… The refreshing originality of mood, harmonization and pianistic invention in these easy, amusing, but provocative compositions from his pen will act as a stimulus and a challenge to all alert student and teachers.

All pedal indications are by the editor. To obtain the rhythm and color required, it is essential that they be strictly observed. Phrasing, slurring and shadings, with very few exceptions. Are the composerʼs own. The fingering is the editorʼs.

The opening “Andantino,” (“Ivan Sings”) composed as early as 1926, is notable for its cantabile melodic writing, its syncopated pedaling, its chromatically descending bass at the opening of the piece (Example 8), and its iambic rhythms in the left hand in the second part of the piece.22 The editor has provided short descriptive commentary of a pedagogical nature at the beginning of each selection as an aid to the pupil and his/her tutor.

After the death of Stalin on 5 March 1953 (the same date of the passing of Prokofiev), Khachaturian once again resumed a place of honor among his compatriots, both musical and political (in the Soviet Union the two were inseparable). He expanded his activities during the 1950s to include conducting his music in more than thirty countries, thereby gaining for it an international audience.

It was also during this time that he developed a career as a teacher at the Gnessin Institute and the Moscow Conservatory, and completed a major ballet, Spartacus, which, after several versions, was reduced to four principal characters: Spartacus, a Thracian slave-gladiator and leader of a revolt of slaves against the power of Rome in 73 B.C.; Phrygia, his wife; Crassus, a power-hungry general; and Aegina, Crassusʼs concubine.

As with his other ballets, several suites were provided, but unlike the earlier works in this genre, folk dances and Soviet subject matter are eschewed. The music is lush, colorfully orchestrated, and neoromantic in its style. The “Adagio of Spartacus and Phrygia” has been extracted from the ballet and become widely popularized through its use as the theme for The Onedin Line, a British television series which ran for nine years beginning in 1971, and by way of the song, “Journeyʼs End,” recorded in 1984 by the American pop singer, Andy Williams.

Pragmatism and Innovative Traditionalism

During the post-Stalin era, the composer wrote many songs and choral works, several important piano works, including a second Childrenʼs Album for piano, a Sonatina in C major, a Sonata in E-flat major dedicated to his teacher, Nikolai Miaskovsky, a set of Recitatives and Fugues, a Sonata-Fantasy for solo violoncello, a Sonata-Monologue for solo violin, a Sonata-Song for solo violin, and, very importantly, three works for solo instrument (one each for violin, cello, and piano) and orchestra with the title Concerto-Rhapsody.

These one-movement works, truncated and formally innovative, recall the earlier Concerti for the same instruments; however, the unusually placed cadenzas, combined with folk-like and elegiac sections, arrest the listenerʼs attention by virtue of the unpredictability of the musical events.

Khachaturianʼs fondness for mixing, matching, and altering works of his own from different time periods in his career is observable in Book II of Childrenʼs Album, wherein three of the pieces were composed in the late ʼ40s, the first two of them with different titles. The closing Fugue, in C minor, dates from as early as 1928, while the remainder of the Album dates from 1964-1965.23 With regard to the Recitatives and Fugues, it is instructive to note that the fugues were composed originally as early as 1928-1929. Of the work as a whole, its creator provides his

own self-effacing assessment:

At that time, I was studying composition under Mikhail Gnessin at the Music College … I wrote seven fugues for piano, which must have been far from perfect. Now, viewing them with the eyes of a mature musician after the lapse of more than four decades, I have rewritten some of them while noting with gratification that many of them contain intonations that I have been partial to all my life. I have added a recitative to each of the seven fugues.

The traditional use of an opening prelude to precede a fugue in works such as this, such as was employed by his colleague, Dmitri Shostakovitch, in his collection of 24 Preludes and Fugues of 1952, has been supplanted by the recitative in order to infuse an Armenian flavor to this example of comingling European formal traditions with the national musical traits of Khachaturianʼs ancestral homeland.

The opening of No. 4 contains some of the latter traits which, by this time, have become musical markers of the composer, among them the shifting triple-duple meters, melodic ninths by way of connected augmented and diminished fifths, and motoric ostinato patterns in the left hand with alternating perfect fifths and diminished sevenths (Example 9) and chromatically descending scalar patterns in the bass.

The Sonatina in C major,25 another impressive contribution to the student pianistʼs repertory, dates from 1958 during which year Khachaturian and Dmitri Kabalevsky made a tour of a coal mining area, the Kuznetsk Coal Basin. The immediate impetus for the work was a visit to a music school in Prokopyevsky; indeed, it is dedicated to students enrolled in the Prokopyevsk Elementary School.

The three movements are marked, respectively, Allegro giocoso, Andante con anima, rubato, and Allegro mosso. In a performance time of approximately seven minutes, the Sonatina contains characteristics observed in the Childrenʼs Albums, including ascending and descending scalar passages in octaves and broken octaves, considerable chromaticism, and a variety of touches, interpretive directions, and tempo changes as exemplified by such markings as marcato, espressivo, poco accelerando, poco più mosso, piano subito crescendo, et alia.

With his contributions to childrenʼs piano literature, Khachaturian takes his place besides his compatriots Kabalevsky, Shostakovitch, Prokofiev, and Gretchaninov, each of whom contributed importantly to this oft-neglected genre. It is important to recall that it was Soviet pianist Emil Gilels who is remembered for his chiding of Soviet composers for not devoting sufficient creative energy to enhancing the piano repertory in general, and it was this same artist and pedagogue who introduced

Khachaturianʼs major solo piano composition, the Sonata in E-flat major-C major to the world, in 1961.

This three-movement opus, revised during 1976-1978, is, in many ways an “adult” extension of the Sonatina.26 The opening Allegro vivace, in cut-time, with its plethora of sixteenth-note rhythms, chromatic scalar patterns, numerous thirds and octaves, cluster chords, and eventual meter changes, including 5-8, 6-8, and 6-4, provides an ample supply of pianistic fireworks. Given that the dedication is to the composerʼs teacher, Nikolai Miaskovsky, the general atmosphere appears to be antipodal to the expectation.

The second movement, Andante tranquillo, opens softly and in an elegiac musical environment, but it changes in midstream to a contrasting Allegro ma non troppo, marcatissimo e pesante, and dynamically fortississimo, before closing with suggestions of tolling bells and a four-measure coda, Lento. The final movement, Allegro assai, with the familiar cluster chords, chromatic scalar passages, and a Prestissimo coda, envelopes the listener in an aural maelstrom.

At the conclusion, the clanging, menacing, bell-like and dissonant chords at a quadruple f level and including iambic rhythms in 3-4 meter alternating with others in straightforward 4-4, lead to combined seventh and ninths chords with superimposed perfect fifths and fourths in the right hand as the tempo broadens (poco a poco allargando) and paves the musical road to a tension-releasing triumphant a tempo, fff, C major chord (Exampe 10). For the pianist, and presumably for the audience, this is the long-awaited moment of release.

The Concerto-Rhapsody in B-flat minor for violin and orchestra, written for and dedicated to Leonid Kogan, was premiered by the latter on 7 October 1962; the Yaroslavl Philharmonic Orchestra was conducted by I. Gusman. On November 7 of the same year, Kogan performed the work with the Moscow Philharmonic Orchestra under the direction of Kyril Kondrashin.

After the presentation of introductory material consisting of a somewhat edgy but familiar chromatically descending melody in the strings and brass and then, by way of contrast, a descending passage featuring flutes and harp, with the violins, not to be ignored, rendering a series of diminished fifths, the soloist emerges with a cadenza (Example 11), serving to prepare for the initial theme over chords in the winds.

There follows in quick succession a folk-flavored lively atmosphere presaging a more emotive rendering of the principal theme with which Part I closes; however, before one can absorb what has transpired, a Gypsy-styled theme is offered by the solo violin with brass and percussion enlivening the proceedings before the initial theme returns followed by the descending figure of the opening portion of the work. The soloist and orchestra then join forces to bring this hybrid composition to a brilliant and, as expected in concerted works by Khachaturian, highly virtuosic conclusion.

The Concerto-Rhapsody in D minor for violoncello and orchestra, written for and dedicated to Mstislav Rostropovich, was first performed in 1963 by the famed virtuoso at the Royal Festival Hall in London with George Hurst directing the London Symphony Orchestra; the cellist gave its first performance in the Soviet Union in Gorky on 4 January 1964.

The Concerto-Rhapsody in D-flat major, the key of the Piano Concerto, received its first performance on 9 December 1968; Nikolai Petrov was the piano soloist with Gennady Rozhdestvensky conducting the Soviet All-Union Radio and Television Symphony Orchestra. Traits similar to those of the violin work described earlier dominate here as well.

The Cello Concerto-Rhapsody, e.g., begins with a prominent horn call which returns to usher in the fiery conclusion of the work with its Armenian dance flavor. The cello cadenza following the Introduction is, as in the other rhapsodies in this trinity of compositions, a “show-stopper.” The scoring, in the piano essay, actually begins with a cadenza (Example 12)! The work is notable for its percussion, which, in this instance, includes xylophone, marimba, and vibraphone.

And, as if reflecting on earlier styles acceptable to the Soviet regime, one finds throughout the piano Concerto Rhapsody, motoring rhythms mixed with folk-flavored lyricism, yet another example of the composerʼs conflation of the polarities that existed in the aesthetic inclinations within Soviet officialdom as well as within the Composerʼs Union during the establishment of Soviet Realism as a guiding principle for creative artists.

A final trilogy, for solo stringed instruments, composed during the 1970s, comprises the Sonata-Fantasy for violoncello (1974), the Sonata-Monologue for violin, and the Sonata-Song for viola (1976). It is consequential that the maestro chose to add hyphenated descriptors for each work as a way to impart the very personal attributes each was meant to convey.

As with other twentieth-century composers who contributed to the solo string repertory among their final creative statements (Ernest Bloch, e.g., composed three suites for solo cello, two suites for solo violin, and an incomplete suite for solo viola) there is a plumbing of the depths, an effort to penetrate the core, the very essence, of what that instrument was capable of expressing on behalf of the composer.

As with the earlier creations, the sonatas reveal a mixture of the improvisational style associated with the ashugs of old and a musical language more contemporary than that with which Khachaturian has been associated in his earlier creative endeavors.

Each of these final efforts, however, does contain traits that have become familiar, viz. a generous array of thematic materials and offshoots derived from them; stylistic contrasts, notably those whereby virtuosic display and long-breathed lyrical lines vie for attention; and folk-flavored, even literally quoted, tunes of Armenian derivation.

The viola sonataʼs subtitle, “song,” seems particularly apt, for its cantabile sections treat the solo instrument as if it were approaching the qualities of the human voice. The closing Sostenuto illustrates this quality effectively.

The Closing Years and Beyond

Throughout the 1950s and continuing to his final years, Khachaturian widened his circle of musical friends and admirers by extending his career to include conducting—in the main, concerts of his own compositions. In so doing, his reputation as a creative artist grew exponentially. His public appearances took place not only in the major cities of the Soviet Union, but also in eastern and Western Europe, Japan, Latin America, and the United States. To be sure, he often acted as a spokesperson on behalf of the ideals of his country and, in particular, those of Soviet Realism, thereby improving his status among Soviet officialdom.

Recorded performances of his works contributed further to his reputation as a composer-conductor despite the fact that, during the post-Soviet era, his name began to wane somewhat in comparison to his one-time cohorts among the “formalists.” It is significant that by the early 1980s, awareness of his Armenian roots spread to the larger world of music, in part because of events in Armenia itself.

In 1982, e.g., the home in which the composerʼs brother Vaghinak and his family resided was opened as a museum and managed by the conductor Goar Agaievna Arutyunian. Its collections include many letters, manuscripts of scores, books, thousands of CDs, photos, and other items related to the life and works of Khachaturian.

The composerʼs son, Karen, has donated personal items of his father, such as his cabinet, dining room, bedroom, piano, and baton. The museum also contains a small recital hall in which many younger performers, especially of chamber music, have displayed their talent. Of more general interest, there is also located here a workshop for restoring stringed instruments, as well as a collection of musical instruments intrinsic to the country.

By the 1990s, Yerevan became the site for the International Cultural-Educational Association “Aram Khachaturian,” an organization whose purpose was to promote the study and performance of the maestroʼs music on a worldwide basis. In addition to its involvement in matters related to the composer, the Association also serves as an advocate for Armenian culture in all its dimensions.

From a political perspective, it is important to recall that the national anthem composed for Armenia in 1944 by Khachaturian when that country was one of the Soviet Socialist Republics was replaced on 1 July, 1991 by Mer Hayrenik (“Our Fatherland”), its first national anthem (1918-1920). In December 1991 Armenia became a member of the Commonwealth of Independent States, the name applied to the former Soviet Union. The anthemʼs opening text conveys the new order:

“Our Fatherland, free, independent, /That has for centuries lived,/Is now summoning its sons/To the free, independent Armenia.”

Conclusion

It is significant that Aram Khachaturian was known through most of the twentieth century as a “Soviet composer,” and his views on Communism suggest that the appellation has merit. He expressed enthusiastic support for the doctrine throughout his life; indeed, as early as 1920, he evinced visible support when Armenia was pronounced a republic of the Soviet Union.

He did so by joining a group of Georgians of Armenian heritage who embarked upon a train-tour of Armenia to commemorate the event. It was twenty-three years later, however, that he officially became a member of the Community Party. Following the Zhdanov denunciation of 1948, he made the obligatory speech of repentance, and continued to display in his music and in personal discourse the evidence of a true believer in the doctrines of Soviet communism, including atheism.

Subtle changes in how he is viewed in academic circles can be observed by noting that, in the 1954 edition of Groveʼs Dictionary of Music and Musicians, he is identified as an “Armenian composer,” while he is identified as “Soviet” in the 1980 edition of The New Grove Dictionary of Music and Musicians”29 by Boris Schwarz, author of the article on him in that august source, and, again, as Armenian in the article on him by Svetlana Sarkisyan in the second edition of the NGDMM.

Given the breakup of the former Soviet Union (Plate 1), and the reality of the independent countries of Armenia, Khachaturianʼs ancestral homeland, Georgia, his place of birth, and Russia, locus of his principal musical education and career, the world has come to recognize him (Plate 2) much as he recognized himself—as an Armenian, but one not limited to a narrow nationalism, but rather one whose art, in transcending geographical boundaries, has proven capable of speaking to a universal audience.

Article by David Z. Kushner, Professor Emeritus of Musicology, University of Florida, USA.

Best site for sheet music download.

Khachaturian: Ballet Suites | Gayaneh, Spartacus Suites

Track List:

00:00:00 Gayaneh, Ballet Suite: Dance of the Rose Maidens 00:02:41 Gayaneh, Ballet Suite: Aysha’s Dance 00:07:04 Gayaneh, Ballet Suite: Dance of the Highlanders 00:09:01 Gayaneh, Ballet Suite: Lullaby 00:14:54 Gayaneh, Ballet Suite: Noune’s Dance 00:16:39 Gayaneh, Ballet Suite: Armen’s Var 00:18:37 Gayaneh, Ballet Suite: Gayaneh’s Adagio 00:22:37 Gayaneh, Ballet Suite: Lezghinka 00:25:35 Gayaneh, Ballet Suite: Dance with Tambourines 00:28:35 Gayaneh, Ballet Suite: Sabre Dance 00:30:58 Spartacus, Ballet Suite: Introduction – Dance of the Nymphs 00:37:02 Spartacus, Ballet Suite: Aegina’s Dance 00:41:02 Spartacus, Ballet Suite: Scene and Dance with Crotalums 00:44:55 Spartacus, Ballet Suite: Adagio of Spartacus and Phrygia 00:54:38 Spartacus, Ballet Suite: Dance of the Gaditan Maidens – Victory of Spartacus

Browse in the Library:

Or browse in the categories menus & download the Library Catalog PDF: