Thelonius Monk‘s sheet music transcriptions are available from our Library.

Chords and Voicings: From Lead Sheet to Performance

In modern jazz, seventh chords specified by lead sheets may appear simply as shown in figure 4.2a, but musicians rarely follow what the lead sheet specifies to the letter. Well before Thelonious Monk came on the scene, jazz pianists vied to distinguish themselves with ingenious voicings. A kind of common practice prevailed in bebop, though we emphasize that musicians can and did step outside this practice in search of particular expressions and logics. In the main, though, four complementary techniques developed, two concerning voicing as such and two concerning chord choice—what chord to play where:

Voicing

• Extension and omission: addition of tones foreign to the chord proper, and/or dropping tones that are part of it

• Spacing and doubling: distribution of a voicing on the piano or among instruments in an ensemble.

Harmonic choice

• Substitution: replacement of one chord by another with equivalent function

• Insertion and deletion: increase or decrease in the rate of harmonic motion by adding to or subtracting from changes specified on the lead sheet.

Extension, omission, spacing and doubling

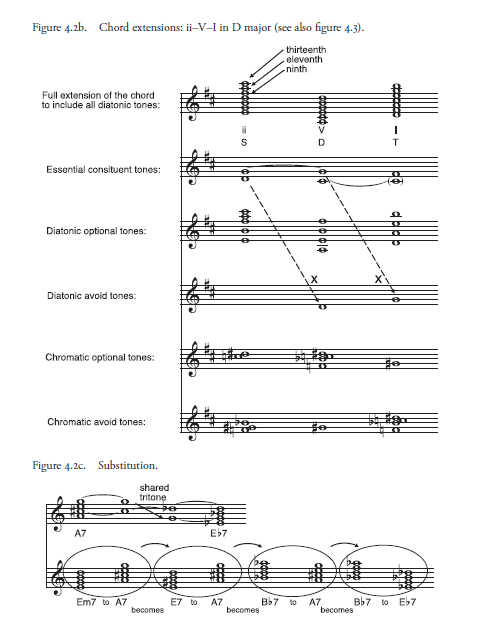

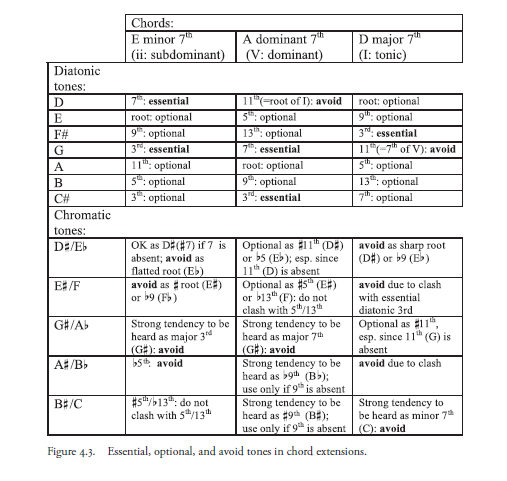

Figures 4.2b and 4.3 illustrate possibilities for extending minor seventh, dominant seventh, and major seventh harmonies, and apply them to the initial ii–V–I of ISC. In the first staff each chord is extended upward by thirds beyond the seventh to include the ninth, eleventh, and thirteenth above the root. Each of the resulting seven-note stacks of thirds includes all notes of the D major scale. The fact that all three chords extend through the exact same pitch collections, in the same intervallic arrangement (i.e., a stack of thirds), demonstrates the fundamental role that harmonic function—and not chord or voicing—plays in determining tonal meaning in jazz.

The chords could in some cases even be voiced in identical ways, but their functional context would make them heard and understood differently. Here is a significant way in which, it seems to us, jazz harmony differs in emphasis from European practice.

To the extent that the distinction between ii, V, and I voicings blurs, what is it precisely that distinguishes their functions? The second staff shows which of the seven diatonic tones are directly involved in the progression toward and away from the V chord’s tritone.

Typically, these tones are necessary and sufficient to convey harmonic function. Surprisingly for anyone familiar with European harmony, neither the fifth nor the root of the chord are necessary; indeed these may be dropped (and possibly supplied by a bass player, but not necessarily). But in order to convey function and quality most effectively, the essential tones are typically arranged in the lower register of the voicing, with extension tones higher up.

The third staff of figure 4.2b distills the optional diatonic tones, which may be used without diluting function or quality, and the fourth staff shows how the tonic note (D) and the fourth scale step (G) are carefully avoided in the dominant and tonic chords, respectively, so as not to carry them over from the chords that precede them, which would impede the ii–V–I motion (see dashed arrows).

Outside the diatonic pitch collection remain fi ve tones completing the chromatic aggregate, which can provide rich “upper structures” to voicings. In some cases these work against important diatonic intervals; for example, using a G with the Em chord could obscure the minor third between E and G; using it with the A7 chord would weaken the C#/G tritone. But with the DM7 it sounds all right because its diatonic “shadow,” G, is already avoided. Figure 4.3 sketches the effect of chromaticism in each chordal context.

All optional diatonic and chromatic tones may be withheld or used, and they may be spaced from low to high in limitless ways. Attention is paid to the choice of lowest pitch, the registers of all others, thickness (number of notes played at once), and the use of some pitches in more than one octave doubling. This topic is discussed later in reference to specifi c instances in short excerpts by pianists Bill Evans and Oscar Peterson (figures 4.4a and b), and also at length in relation to Monk.

Chord Substitution, Insertion, and Deletion

Because every dominant-quality seventh chord shares its tritone with the dominant-quality seventh chord whose root is a tritone away, the chords in each such pair may be substituted for one another ( figure 4.2c, first staff).

Substitutions for V are idiomatic in ii–V–I motion. In D major, this turns Em7–A7–DM7 into Em7–Eb7 –DM7 and causes the roots to descend chromatically by half step rather than by fifth, an especially characteristic marker of modern jazz sound. The second staff of figure 4.2c illustrates another kind of substitution, involving change of chord quality. In the first stage, the ii of

the ii–V–I progression is intensifi ed by raising its third from G to G# . This makes it E7, a dominant seventh chord, that is, V7 in relation to the A7 chord, and thus “tonicizes” the root of A7 as if A were momentarily the home key. From here it is a matter of applying the tritone substitution principle just discussed to convert the pair of chords into progression from Bb7 to Eb7. Monk does just this in ISC ( figures 4.1 and 4.5 , mm. 15-16).

Harmonic rhythm is the rate at which harmonies change. A scan of the various versions of ISC in figure 4.1 shows chords changing usually every two or four beats, though Oscar Peterson achieves special intensity in mm. 1-2 by changing on each beat, and there are scattered instances of chords held longer. Since harmony’s depth of field is rich, even with these severe constraints on harmonic rhythm there can be infinite ways to realize the harmonies in a song and suggest unexpected aural routes through it.

Sometimes root progressions by fifth are concatenated, as in figure 4.1, staff 2, mm. 2-3. Here, rather than have mm. 3-4 be a repetition of mm. 1-2, as it is in Monk’s version (staff 3), the ii chord of m. 3 is treated as a local tonic and preceded by its own ii–V. The two new bass tones F and B are part of the D major scale, so the motion feels activated but the connections do not jar.

The major third (D#) of the B7 chord is the only chromatic alteration implied. In Bill Evans’s version, the bass player faithfully provides the root tones (figure 4.4b), but Evans does not reflect the change on the piano. Without the D#, the feeling of tonicization is absent, and we have labeled the chord as Bm7.

Earlier we mentioned a more deeply hued insertion, at mm. 8 and, which introduces a ii–V (Gm7 to C7) progression borrowed from F major, a key built on a tonic foreign to the D major scale. This motion is so distinctive that it might be heard as one of the strongest markers of the song as a whole. In the fake book version, after slipping momentarily toward F in this way the music slips right back to DM7 in m. 9.

Monk, however, reinterprets the C7 as a tritone substitution for an F#7, and resolves in m. 9 to Bm7 (the fake book does this too, but later, at the parallel moment in mm. 25). Another insertion in the fake book version, reflecting a mix of diatonic and chromatic moves, comes at the final measures (31-2).

This characteristic “turnaround” revs up the motion, propelling the music toward the next repetition of the form. Monk’s seeming extension of this passage and the two prior measures reflect a musical action we shall describe later; in figure 4.1 we condense his chords into the thirty-two-measure form (the actual measure numbers cor-responding to mm. 29-38of the transcription in figure 4.5 are shown below the lowest staff).

Deletions put the brakes on chord progression. In this idiom they are somewhat rarer than insertions but noteworthy for that reason. When Monk slows down the fake book chords at m. 2 he wants to focus on the very repetition of the chord progression in the initial two pairs of measures, and when he does it again at mm. 15-16 it is as if we are asked to savor the tritone substitutions selected for those moments.

Modern jazz harmonic practice often seems to be founded on the intensifi cation and complexifying of its diatonic basis in the several ways we have just described all at once—so the instances in which this process is slowed or impeded provide a special repose.

Browse in the Library:

Or browse in the categories menus & download the Library Catalog PDF: