Come join us now, and enjoy playing your beloved music and browse through great scores of every level and styles!

Can’t find the songbook you’re looking for? Please, email us at: sheetmusiclibrarypdf@gmail.com We’d like to help you!

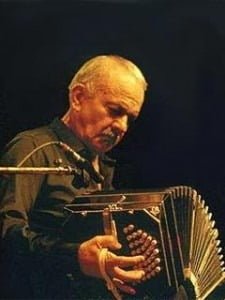

Astor Piazzolla (1921-1992): Tango Revolution

Astor Piazzolla

Without the shadow of a doubt, Astor Piazzolla (1921-1992) is the single most important figure in the history of the tango! While Carlos Gardel and Ángel Villoldo are credited with creating the “tango canción”—a subgenre that realistically reflected the life of the lowest classes of society— Astor Piazzolla is rightfully considered the father of the “tango nuevo.” A genius composer and performer, he revolutionized the traditional tango by turning disreputable and downright earthy folk music into a sophisticated form of art.

Tango Revolution

Piazzolla incorporated elements from jazz and classical music into the traditional tango, and introduced new forms of harmonic and melodic structure into the tango ensemble. And that included the integration of novel instruments, such as the saxophone and electric guitar.

This ingenious fusion of the tango with a wide range of recognizable Western musical elements—including counterpoint and passacaglia techniques—not only produced a new and unique musical style that transcended all earlier expressions, it also significantly contributed to the continued evolution of this art form.

Piazzolla died in his beloved Buenos Aires 25 years ago, and in 2017 we celebrate the monumental legacy of one of South America’s greatest musical figures.

Astor Piazzolla: Oblivion (Guitar ver.)

Early Days

The only child of Italian immigrant parents, Astor Piazzolla was born in Mar del Plata, Argentina, but essentially spent his childhood in Greenwich Village in New York City. For his 9th birthday, his father gave him a bandoneon and Astor started to take lessons. Eventually he studied with Hungarian pianist Bela Wilda, a student of Rachmaninoff, who taught him to play Bach on his bandoneon.

Piazzolla composed his first tango and he met Carlos Gardel, who invited him on his tour to South America. His father decided that he was not yet old enough to go along, and forbid him to join the tour.

The initial disappointment proved fortunate, as Gardel and his entire orchestra perished in a plane crash in 1935. Piazzolla later joked, “If my father had not been so careful, I would be playing the harp rather than the bandoneon.” Once the family returned to Mar del Plata, Piazzolla played in a variety of tango orchestras and eventually moved to Buenos Aires.

He soon realized his dream of joining the orchestra of widely renowned bandoneonist Anibal Toilo in 1938, and on the advice of pianist Arthur Rubinstein took lessons from composer Alberto Ginastera and pianist Raúl Spivak. For 5 years, Piazzolla studied the scores of Ravel, Bartók, and Stravinsky alongside compositions originating from American jazz.

Libertango (piano solo arr.)

Tensions mounted between Piazzolla and Troilo, who feared that the advanced musical ideas of the young bandoneonist might undermine the style of his orchestra and make it less appealing to dancers of tango. In 1944, Piazzolla left Troilo’s group, and unsure of his musical directions, briefly left the tango and bandoneon behind to compose a number of film scores.

He furthered his musical studies with the conductor Hermann Scherchen, and in 1953 entered his composition Buenos Aires into the Fabien Sevitzky competition. The work elicited strong reactions as it featured the inclusion of two bandoneons into the symphonic orchestra.

However, it also won him a scholarship from the French government to study with Nadia Boulanger in Paris. Boulanger strongly encouraged Piazzolla not to ignore tango, but to infuse the traditional form with his jazz and classical training. “Astor,” she said, “your classical pieces are well written, but the true Piazzolla is in the tango, never leave it behind.”

When he returned home in 1955 he immediately formed the “Octeto Buenos Aires,” a legendary group that played tango as self-contained chamber music. Tango purists were not amused, and eventually forced him into exile in New York City where Piazzolla further experimented with a fusion of jazz and tango.

Milonga del Angel (Piano solo with sheet music)

International Recognition

Once he returned to Buenos Aires in 1960, Piazzolla refined and experiment heavily with all aspects of tango. His collaboration with poet Horacio Ferrer produced the groundbreaking “little opera” Maria de Buenos Aires, and a series of tango songs.

Piazzolla’s music started to gain international recognition, and when Argentina’s government was taken over by a conservative military faction, he decided to move to Italy. A series of recordings that would span a period of five years included the famous Libertango, and in 1982 the album Oblivion.

Extensively traveling the world, and at the height of his international fame, Piazzolla underwent quadruple bypass surgery in 1988. He sufficiently recovered to go on tour in 1989, but a severe stroke left him in a coma and he died two years later on 4 July 1992.

Piazzolla considered the fusion of tango with the music of Bartok and Stravinsky “the tango of the future,” and the complexity of his oeuvre brought him international acclaim and a secured place in the history of 20th century music.

Oblivion (2 pianos)

Piazzolla’s musical analysis:

APPROACHING PIAZZOLLA’S MUSIC: an analysis of his music and composition styles (1/2)

APPROACHING PIAZZOLLA’S MUSIC: an analysis of his music and composition styles (2/2)

Browse in the Library:

Or browse in the categories menus & download the Library Catalog PDF: