- Rachmaninoff – Symphony No. 2 in E minor, Op. 27 3rd mov. Adagio (Easy piano solo arrangement) with sheet music

- The Symphony No. 2 in E minor

- History

- Music

- Scoring

- Movements

- First movement

- Second movement

- Third movement

- Fourth movement

- Manuscript

- Derivative works

- “Rachmaninoff’s Piano Concerto No. 5”

Rachmaninoff – Symphony No. 2 in E minor, Op. 27 3rd mov. Adagio (Easy piano solo arrangement) with sheet music

The Symphony No. 2 in E minor

Op. 27, is a symphony by the Russian composer Sergei Rachmaninoff, written in 1906–07. The premiere was conducted by the composer himself in Saint Petersburg on 8 February 1908. Its duration is approximately 60 minutes when performed uncut; cut performances can be as short as 35 minutes. The score is dedicated to Sergei Taneyev, a Russian composer, teacher, theorist, author, and pupil of Pyotr Ilyich Tchaikovsky. Alongside his Prelude in C-sharp minor, Piano Concerto No. 2 and Piano Concerto No. 3, and Rhapsody on a Theme of Paganini, this symphony remains one of the composer’s best known compositions.

History

At the time his Symphony No. 2 was composed, Rachmaninoff had had two successful seasons as the conductor of the Imperial Opera at the Bolshoi Theatre in Moscow. He considered himself first and foremost a composer and felt that the performance schedule was detracting from his time to compose.

He then moved with his wife and infant daughter to Dresden, Germany, to spend more time composing and to also escape the political tumult that would put Russia on the path to revolution. The family remained in Dresden for three years, spending summers at Rachmaninoff’s in-law’s estate of Ivanovka. It was during this time that Rachmaninoff wrote not only his Second Symphony, but also the tone poem Isle of the Dead.

Rachmaninoff was not altogether convinced that he was a gifted symphonist. At its 1897 premiere, his Symphony No. 1 (conducted by Alexander Glazunov) was considered an utter disaster; criticism of it was so harsh that it sent the young composer into a bout of depression. Even after the success of his Piano Concerto No. 2 (which won the Glinka Award and 500 rubles in 1904),[1] Rachmaninoff still lacked confidence in his writing. He was very unhappy with the first draft of his Second Symphony but after months of revision he finished the work and conducted the premiere in 1908 to great applause. The work earned him another Glinka Award ten months later. The triumph restored Rachmaninoff’s sense of self-worth as a symphonist.

Because of its formidable length, Symphony No. 2 has been the subject of many revisions, particularly in the 1940s and 1950s, which reduced the piece from nearly an hour to as little as 35 minutes. Before 1970 the piece was usually performed in one of its revised, shorter, versions. Since then orchestras have used the complete version almost exclusively, although sometimes with the omission of a repeat in the first movement.

Music

Scoring

The symphony is scored for full orchestra with 3 flutes (3rd doubling piccolo), 3 oboes (3rd doubling cor anglais), 2 clarinets in A and B♭, bass clarinet in A and B♭, 2 bassoons, 4 horns, 3 trumpets, 3 trombones, tuba, timpani, snare drum, bass drum, cymbals, glockenspiel, and strings.

Movements

The symphony is in four movements:

First movement

The first movement begins with a slow, dark introduction, in which the ‘motto’ theme of the symphony is introduced and developed. This leads to an impassioned climax, after which a cor anglais solo leads the movement into the allegro in sonata form. Assuming the symphony is performed uncut, this also includes a full repeat of the exposition.

In contrast to the exposition, the development is stormy at times and moves through multiple key centres. Only the first subject and central motto theme are used in the development. After a long dominant pedal, the music slowly transitions to the recapitulation in E major, in which only the second subject is recapitulated, but is heavily expanded on compared to the exposition. This device of omitting the first subject from the recapitulation was also used by Tchaikovsky in his second, fourth and sixth symphonies. The coda in E minor builds up intensely and the movement culminates in two fortissimo outbursts.

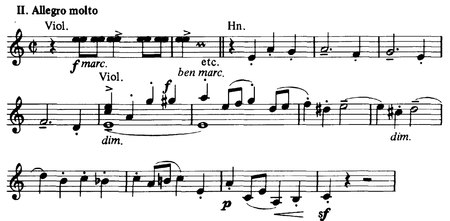

Second movement

This movement really only resembles a scherzo insofar as it relates to the early- to mid-Romantic tradition of symphonic movements, and its use of a typical scherzo form (ABACABA). However, it is in 2/2, while the typical scherzo would be in 3/4 or some kind of triple meter. The movement, in A minor, opens with a lively ostinato in the upper strings. As a fixture in large-scale works by Rachmaninoff, the Dies Irae plainchant is referenced, here in the opening bars by the horns.

The B section is a lyrical cantabile melody in C major. The music slows down and the opening ostinato is referenced, and in returning to the A section it abruptly speeds back up to its opening tempo. The central trio section notably begins with a sudden, tutti, fortissimo B Dominant 7th chord, and is an example of Rachmaninoff’s mastery of counterpoint and fugal writing, thanks to his studies with Taneyev, to whom this symphony is dedicated. At the conclusion of the movement, the Dies Irae is again stated, this time by a brass choir. The momentum dissolves, and the movement ends pianississimo (ppp).

Third movement

This movement is in a broad three-part form, and is often remembered for its opening theme, which is played by the first violins and restated both as a melody and as an accompanying figure later on in the movement. This opening theme, however, is really an introduction to the main melody of the movement, which is presented by a lengthy clarinet solo, and is a typical Rachmaninoff creation, circling around single notes and accompanied by rich harmony.

The development is based on the Dies Irae motto theme of the symphony, as if it was continued on from the first movement’s introduction. A chromatic buildup leads to an impassioned climax in C major. The intensity subsides, and the central melody of the third movement is restated, this time played by the first violins, while fragments of the opening theme are heard in the accompaniment. The Dies Irae motto is restated again apparently to bring about an ending to complement the first movement introduction, as the third movement concludes in a tranquil fashion dying away slowly in the strings.

Fourth movement

The final movement is set in sonata form. The lively, fanfare-like first theme, derived from the first “Dies Irae”-like theme of the Scherzo, is played by the entire orchestra, leading into a march-like interlude starting in G# minor played by woodwind.

After the return of the first theme, the first subject is concluded, and transitions directly into a massive, broad melody in D major played by strings. After dying down to pianissimo, the opening theme of the third movement, this time in D major, is briefly recalled over string tremolos. After an abrupt interjection, the development section begins, which is in two sections, the first of which introduces new melodic ideas, and the latter of which revolves around a descending scale.

The recapitulation initially only presents the first subject, before moving into a dominant pedal, building up to the triumphant restatement of the broad melody now in the home key of E major, in which fragments of the first theme, motto theme, and descending scale can be heard in the accompaniment. A whirlwind coda brings the symphony to a close, with a fortissimo restatement of the brass chorale that appeared at the end of the second movement.

The final bars present another fixture of Rachmaninoff’s large-scale works, the characteristic decisive four-note rhythm ending (in this case presented in a triplet rhythm), also heard in his Cello Sonata, second and third piano concertos, and in an altered form in his fourth piano concerto and Symphonic Dances.

Manuscript

The manuscript had been thought lost, until its discovery in the estate of a private collector in 2004. It was authenticated by Geoffrey Norris. It contains material that has not found its way into any published edition.The manuscript became the property of the Tabor Foundation, and was on permanent loan to the British Library.

In May 2014 the manuscript was auctioned by Sotheby’s for £1,202,500.

Derivative works

A section of the symphony’s second movement is used several times in the 2014 film Birdman, directed by Alejandro González Iñárritu, and is even used in the trailers promoting it. It is featured as part of a score composed by Mexican jazz drummer Antonio Sánchez.

Operatic tenor, Christian Ketter’s arrangement of Rachmaninoff’s Zdes Khorosho (Здесь хорошо/ How Fair This Place) Op. 21, No. 7 quotes the symphony’s paralytic third movement in its introduction on the 2014 recording, “Beloved: live in recital.”

Parts of the third movement were used for pop singer Eric Carmen‘s 1976 song, “Never Gonna Fall in Love Again“, which borrowed the introduction and main melody of the third movement as the song’s chorus and bridge, respectively. As Rachmaninoff’s music was still in copyright at the time (it has since expired in most countries), Carmen was made to pay royalties to the Rachmaninoff estate for the use of the composer’s music, both for the aforementioned song and “All By Myself“, which borrowed from his second piano concerto in its verse. The melody was also used by jazz pianist Danilo Pérez as the main theme of his tune “If I Ever Forget You” on his 2008 album Across the Crystal Sea.

“Rachmaninoff’s Piano Concerto No. 5”

In April 2008 Brilliant Classics released Alexander Warenberg’s arrangement of the symphony for piano and orchestra, titling it “Rachmaninoff’s Piano Concerto No. 5”. Warenberg arranged Rachmaninoff’s Symphony No. 2 as a concertante work for piano and orchestra. The work contains about 40% of the source material from the symphony with some original scoring by Warenberg, modification of the original score and a change to many of the harmonies “to improve the sound and balance”. Warenberg’s arrangement is a three movement concerto with a new second movement and a revised finale “to create a tighter and more effective emotional climax to the concerto’s finale.”

For the concertante’s first movement, the slow introduction developing the main motif is shortened from the symphony with the material not discarded but instead shifted to the concertante’s cadenza immediately after the climax. The concertante’s second movement largely following the symphony’s third movement, except for immediately after the climax when the exposition of the symphony’s second movement is inserted, before returning to the symphony’s third movement recapitulation.