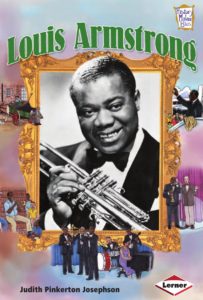

Book review: “Hotter Than That: The Trumpet, Jazz, and American Culture”. By Krin Gabbard.

New York: Faber and Faber, 2008.

A swinging cultural history of the instrument that in many ways defined a century

The stated purpose of this latest book by Krin Gabbard, Professor of Comparative Literary and Cultural Studies at Stony Brook University, is “to write a cultural history of the trumpet,” posing the question: “What did the trumpet mean to American history, but also, what did the trumpet mean to the men and women who played it?” To address these issues Gabbard includes chapters on the role of the trumpet through history; the manufacture of present day trumpets; and an account of his experience learning to play the horn (“the most difficult of all instruments”). But the main thrust of the book (pardon the crude sexual allusion) is to focus on the trumpet as a “symbol of manhood,” “masculine signifier,” and emblem of “masculine display.”

“For more the thirty-five hundred years,” Gabbard writes, “the trumpet has served its purpose in male-centered activities such as war, religious ceremony, and royal pageantry. In the early twentieth century, African American men made brilliant use of the trumpet to assert that they were men and not boys. Many of these black men were single-mindedly devoted to making great music, but they may have also found the trumpet to be the ideal instrument for telling the world that they were not merely manly but extremelymanly.” Gabbard further states, “If these men had tried to express their masculinity and sexuality in just about anyother fashion, they would have been lynched.”

Thus Buddy Bolden was not only the first celebrated jazz musician, but he also “invented a new breed of masculinity, essentially teaching subsequent generations of black men how to strut their stuff as men while delighting the same whites who might otherwise have brutally punished their expressions of black masculinity.” According to Gabbard, Bolden “might have paid with his life for a comparable assertion in almost any other venue.

Browse in the Library:

Or browse in the categories menus & download the Library Catalog PDF:

Along with everything else, Bolden was appropriating the instrument’s long history as a symbol of manhood, whether it was in battle, in the ceremonies of the royal court, or in the religion of God the Father. Buddy Bolden may have been the first American to make the horn as essential to modern America as to the presentation of manhood.” And: “Bolden’s sexuality and masculinity were inseparable from his cornet playing.” Later chapters deal with Louis Armstrong and Miles Davis, and how this nexus of sexuality and overt display of black masculinity in the face of a racist society affected jazz and its acceptance within American culture.

It’s a seductive theory, with all the ingredients of a pot-boiling novel: sex; race; the threat of violence and even death at the hands of a lynch mob; and of course jazz. But to take this hypothesis seriously we are obliged to accept Gabbard’s assertions that the trumpet (or cornet in the case of Bolden) stood as a universally recognized, or at least subliminally prevalent, symbol of manhood; Bolden (we shall discuss the others later) lived and worked in a place where white authority dominated his life, and where fear of violence at the hands of whites was endemic; and Bolden felt a need to prove his manliness to whites, and cared on a deep psychological level how they regarded him.

To bolster his arguments, Gabbard is highly selective in the evidence he presents. Consider the following statement: “Buddy Bolden did more than invent jazz. He took hold of the royal, ceremonial, and military aspects of the trumpet and remade them for black culture.” Though Gabbard occasionally mentions the brass band craze that swept the nation at precisely the same time jazz arose in New Orleans, he is unwilling to place Bolden squarely within this context. Instead, he casts Bolden as a lone, heroic figure, with little or no connection to the hundreds if not thousands of other cornet players, black and white, who were active during this period. By one estimate, 10,000 bands and 150,000 bandsmen performed regularly across America in the early 1890s.

Did Bolden take up the cornet out of a desire to appropriate the trumpet’s rich history as an accessory to power and grandeur, or did he merely wish to play the popular music of his time, granted with a more original and personal approach? It seems much more plausible to me that Bolden, rather than using the cornet to brazenly challenge the status quo, chose the instrument because it was among the most popular and widely available instruments of his time.

Whatever associations trumpets and cornets may have had with ceremonial pomp, in the New Orleans of Bolden’s era metal, trumpet-like horns were frequently seen in the hands of those who plied the most lowly and mundane professions. As Jelly Roll Morton observed, “Even the rags-bottles-and-bones men would advertise their trade by playing the blues on the wooden mouthpieces of Christmas horns.” Louis Armstrong began his instrumental career playing on a similar “tin horn—the kind people celebrate with,” as he made the rounds on a “junk wagon.”

Buglin’ Sam Dekemel was a common sight in old New Orleans as he blew his horn to help sell waffles, four for a nickel.

Gabbard tells us,

In the American South that Bolden knew, a black man was either agreeable and eager to please around white people, or he was strange fruit hanging from a poplar tree…He found a way to assert himself as a man without experiencing the fate of those proud black men who refused to yield to white racism and paid for it with their lives. Because he expressed himself through music, and because whites have always been more fascinated than repelled by black music, he was not punished for his self-expression.

Here we have a picture of a black community beleaguered by fear, and subject to the most horrendous reprisals for asserting themselves in any way. But Gabbard is careful not to mention that Bolden’s neighborhood was very mixed—Larry Shields, the white clarinetist of the Original Dixieland Jazz Band, grew up only two houses down from Bolden—and quite middle-class by the standards of the time. The French-speaking Creole trombonist Edward “Kid” Ory lived only a few blocks away and recalled that Bolden was “always on the box step out in the street on the sidewalk. He never practiced in the house. He blew so loud he’d blow everyone out of the house. The kids gathered around on the sidewalks, yelling ‘King Bolden! King Bolden!’ This is hardly the image of a man wracked with fear over the prospect of violent white reprisals for openly expressing himself.

Mike De Lay was a New Orleans trumpeter born of mixed race and active in the twenties; his father belonged roughly to Bolden’s generation. In a taped interview at the Hogan Jazz Archive of Tulane University (which Gabbard visited to research Bolden), De Lay offers many insights into the unique racial dynamics of New Orleans during this period. De Lay’s father assured him “there was never a Negro lynched in New Orleans.” (The only unfortunate souls lynched in the town may have been a group of Sicilian immigrants in 1891.) De Lay further states, “Nine [times] out of ten, if you was a guy that minded your business, it didn’t matter what color you were…For a Southern place you had more good solid white people in New Orleans than any other Southern place I could think of.”

In Gabbard’s words, “Even if someone like Bolden had to step aside when a white person approached him on the sidewalk, and even if he was regularly referred to as a ‘boy,’ he knew that he possessed everything it took to be a man, including sexual power.” But as De Lay, who was much closer to this era than any of us will ever be, tells it: “In a small town in Louisiana you better get off the streets at night; in Jackson, Mississippi, you’d better get off the sidewalk,” but “New Orleans was the best place for colored people; in New Orleans you were free.”

The record seems clear that Bolden spent nearly his entire career playing in neighborhood dance halls and outdoor amusement parks for audiences of fellow African Americans. These venues offered him every opportunity to “strut his stuff” without fear of violence at the hands of whites. But he may very well have feared what we now call “black-on-black crime,” a fact ignored in the book because it would compromise its central thesis. George Baquet described the Odd Fellows Hall, when Bolden was playing, as “plenty tough.” Jelly Roll Morton also spoke of how Bolden performed “at most of the rough places.” When Morton went to hear Bolden, the pianist narrowly missed being killed in a shooting that left another man dead. Guitarist Danny Barker told of black dance halls where “the undertaker would be glad because there were three or four bodies, and sometimes women’s titties would be chopped off.”

Even in later times and other towns and cities, intraracial violence exacted a toll on black musicians. Bandleader James Reese Europe was stabbed to death by his own drummer. One of Baquet’s brothers, Harold, was gunned down by a dancer outside a Harlem night club. Sidney Bechet did time in a French prison for shooting at fellow musician Gilbert “Little Mike” McKendrick and wounding three bystanders. As Gabbard himself mentions, Freddie Webster may have been murdered by a fatal dose of heroin prepared by a fellow band member. Lee Morgan was shot to death by a spurned lover.

I’m certainly not denying that racism was an evil and corrosive factor in the lives of African Americans throughout the twentieth century. And no doubt racism contributed greatly to violent behavior bred of poverty and despair. But to make his points appear weighty and dramatic, Gabbard is all too willing to jettison any sense of proportion, and consequently his arguments lose touch with reality.

For example, Gabbard claims, “If these men [New Orleans cornetists Bolden, Keppard, Oliver, and Armstrong] had tried to express their masculinity and sexuality in just about any other fashion [than music], they would have been lynched.” But all of these musicians inhabited New Orleans during the age of Storyville, unquestionably the most openly licentious locale in all of America. All manner of sexual conduct was tolerated and in fact legally sanctioned, with virtually limitless opportunities for anyone of any color to indulge. The only taboo in this carnal free-for-all was sex between black men and white women, though Mike De Lay was the product of such a union.

In any case, I doubt this taboo was a major concern to Bolden, Keppard, Oliver, or Armstrong. Oliver was happily married to one woman for most of his adult life, and a large part of the Bolden legend is that he enjoyed a “plentiful supply of the most beautiful ladies in New Orleans,” as one of his contemporaries attested.

Oliver, Keppard, and Armstrong (unlike Bolden) played for whites and in white-owned establishments throughout much of their careers. Even while still in New Orleans, Oliver played for all-white dances at Tulane University. Armstrong, while in Kid Ory’s band, enjoyed a steady engagement at the elite New Orleans Country Club. In his autobiography Satchmo, Armstrong tells of Keppard playing at parties for rich whites in the Garden District. One of the major untold stories in jazz history is how a great many early African American jazz musicians had positive experiences with whites, which later enabled them to function relatively smoothly in a music business dominated by white managers, agents, club owners, and record company executives.

Oliver worked by day for a well-to-do white family that made allowances for him to pursue his musical career. And as Gabbard notes in his book, the poor Jewish Karnovsky family bought Armstrong his first cornet and regularly attended his performances, cheering him on.

Gabbard props up his tenuous positions by restating faulty conventional wisdom regarding early jazz, including a common confusion about the function of music in Storyville. He states, “Very few brothels could afford an entire orchestra or even a quartet of musicians…A brass band would have been completely out of place.” Therefore he concludes that Bolden’s style owed more to the sanctified church than to the music performed regularly within the vice district.

But jazz bands flourished in Storyville, not in the brothels but in the many clubs that formed the “tango belt” on the vice district’s border. Tom Anderson’s Café, where both Oliver and Armstrong played, was just a few steps down Basin Street from Lulu White’s Mahogany Hall, the most lavish brothel in the district. The date of Storyville’s official establishment was January 1, 1898, right around the time Bolden began his career as a musician.

The author also seems confused about why the cornet was favored over the trumpet during this era. “Because the cornet was more compact,” he writes, “it was preferred by late-nineteenth-century musicians, who carried it around in parades and in crowded dance halls.” But by this time the cornet was already well established as a solo and ensemble instrument capable of dazzling virtuosity and expressiveness.

It was perfectly suited for both brass bands and early jazz bands because it blended well with other instruments, without dominating them as a trumpet would. The trumpet gained prominence only when jazz developed into a soloist’s art—especially in the hands of Louis Armstrong—and when music venues shifted from small cabarets, restaurants, and private gatherings to large dance halls and theaters.

Gabbard rightly notes, “We have no way of knowing what Bolden’s trumpet sounded like.” But despite that prudent disclaimer, he proceeds to tell us in great detail exactly how Bolden sounded:

He was preaching with his cornet, imitating the gospel preachers who found untapped resources of vocal volume as they called out to their congregations.

Mixing the blues with the emotional intensity of the Holy Roller church, Bolden also took a more aggressive approach to syncopation.

Growing up in the vast musical culture of New Orleans, Bolden could have learned the art of the emotional vibrato almost anywhere.

Bolden delighted crowds by imitating human speech and even animal sounds.

Bolden could make his cornet moan and growl. He also departed from the ‘legitimate’ technique to shake or smear his notes; as an African American in the South, Bolden had the ‘advantage’ of being excluded from conservatory training. He may not have been sufficiently accomplished to make the lightning-fast runs up and down the horn that would become Louis Armstrong’s trademark, but he was able to make up countermelodies to familiar songs on the spot.

All this is total speculation. Perhaps Bolden consciously imitated preachers and animal sounds, employed vibrato, smeared notes, growled, and made up counter-melodies on the spot. The truth is we just don’t know, and we never will. As a scholar, Gabbard owes it to his readers to draw a clear line between fact and supposition.

Bolden may have “had the ‘advantage’ of being excluded from conservatory training,” but Gabbard does not mention that no conservatories existed in the South at this time for students of any color. Nor does he mention the strong possibility that Bolden did in fact receive a very solid musical education. Donald Marquis, Bolden’s biographer, notes that the cornetist graduated from high school, making him far better educated than most African Americans, as well as many whites, of his time.

Marquis believes he attended the Fisk School for Boys, which had an excellent music program under the direction of two professional musicians, James and Wendell MacNeil.James MacNeil was a highly accomplished cornetist who worked in the Onward Brass Band, the Excelsior Brass Band, and John Robichaux’s popular dance orchestra. It’s quite possible that MacNeil instructed Bolden on the instrument as well as the fundamentals of music. Bolden is listed in city directories first as a “music teacher” and later as a “musician,” which suggests he had some degree of formal training under his belt.

The author occasionally misuses musical terminology, as in his reference to Bolden possessing “a more aggressive approach to syncopation.” I suspect Gabbard intended to say that Bolden exhibited a greater emphasis on rhythm, and specifically syncopation, than his contemporaries (again all speculation). Syncopation may be employed to a greater or lesser degree, but it is incorrect to say syncopation is approached with aggression. Gabbard fails to recognize Bolden’s most enduring contribution to jazz, which was indeed in the area of rhythm—again speculation, though this time borne out by concrete evidence.

By adapting the vocal blues to instrumental music, Bolden brought rhythmic style away from the straight-eighth-note manner common to ragtime, and towards the more rolling “swing” feel we now associate with jazz. King Oliver—who idolized Bolden, as Oliver’s wife testified in an interview for the Hogan Archive—displayed this rhythmic approach even in his earliest recordings. From Oliver, and probably others, it was passed on to Louis Armstrong, and from him to the world.

It is also an error to say that “lightning-fast runs up and down the horn” were a “trademark” of Armstrong’s style. Armstrong typically preferred to play half-time in up tempos, and on those few recordings where he did attempt fast runs (such as the breaks in his solo on “Struttin’ With Some Barbecue,” and the final ensemble in “Ory’s Creole Trombone,” both by the Hot Five), he didn’t execute them cleanly. Armstrong was a consummately melodic player and fast runs were simply not part of his vocabulary. (Later in the book Gabbard refers to the Max Roach band with Booker Little as “solemn in its tonalities.” What does that mean: that they favored minor keys?)

The author also has no compunction about reconstructing Bolden’s thoughts and feelings, though again, no record survives: “Like many trumpeters before and since, he must have relished his ability to astonish listeners with cascades of notes, from the bleating tones at the bottom to the thrilling shrieks at the top”; and later, “He must have taken delight as he lofted lyrics and musical ideas unique to black culture over the heads of his white audience.” Contrary to this image, historical sources suggest that Bolden’s white audience was restricted to no more than a few scattered onlookers at public events.

Gabbard also asserts, “Even a few white people hired him for their parties,” with no citation to substantiate this claim. I’ve never seen any mention of this in the sources I know, which are essentially the same ones the author consulted. Gabbard further states that “Bolden never played in marching bands,” though in fact Bolden’s last remembered public performance consisted of marching in a Labor Day parade in 1906.

Although Bolden is indisputably a key figure in the formation of early jazz, Gabbard is too eager to overstate Bolden’s innovations. Not only did the cornetist single-handedly “invent jazz” (in the author’s words), but the standard Dixieland front line of cornet, clarinet and trombone “almost surely began with Bolden.” However, a cartoon published in the NewOrleansMascoton November 15, 1890, clearly shows a black band playing on a balcony with exactly this front line. At that time Bolden was only thirteen, and several years from becoming a professional musician.

The author also credits Bolden with making “the cornet the main attraction, loudly taking over the role of the violin and essentially ending its dominance in turn-of-the-century dance bands.” But up through the 1920s the violin remained a fixture in many dance bands, and there were a host of African American violin-playing dance band leaders, including Charles Elgar, Armand Piron, Carroll Dickerson, Erskine Tate, and Andy Peer, leader of the first band employed at Harlem’s Cotton Club. Even in New Orleans, after Bolden was institutionalized, surviving photos reveal that the Original Superior Orchestra, the Original Creole Orchestra, and Fate Marable’s band all featured violinists.

The author later presents similarly exaggerated claims about Armstrong and Miles Davis. Armstrong is said to have inspired symphony musicians to play with more vibrato. Classical musicians typically vary their vibratos according to historical style, but I’m sure that any trumpeter who exhibited Armstrong’s characteristic wide and pulsating vibrato would be summarily fired. Likewise, Gabbard claims that Davis, in addition to developing “the most flamboyant revision of the trumpet as masculine signifier,” also “invented” cool jazz, “created” modal jazz, and again “invented” jazz-rock. Davis certainly popularized these trends and of course had a significant hand in creating them, but with considerable help from a host of colleagues (many of them white musicians such as Gil Evans, Gerry Mulligan, John McLaughlin, and Chick Corea).

In fact the contributions of white musicians are given short shrift throughout this book. Gabbard’s philosophical starting point is that jazz is “black music”—end of story. This view reflects a common schizophrenia regarding jazz on college campuses across the country. On the one hand, universities happily take money from legions of young white musicians accepted into the jazz departments of their music schools. At the same time, professors in social and cultural studies loudly proclaim that jazz is black music: the unique and deeply ingrained artistic expression of an oppressed people. Thus jazz is the birthright and intellectual property of African Americans, regardless of whether or not they own an instrument or even listen to the stuff.

This view was pioneered by ex-SUNY Stony Brook professor Amiri Baraka (back when he was LeRoi Jones), whose work is referred to by Gabbard as “ambitious and provocative.” I am sincerely grateful that Toni Morrison, August Wilson, Alvin Ailey, and Jessye Norman aren’t accused of appropriating white culture. But when white musicians play jazz—and even Gabbard admits they’ve contributed to the music since the 1880s, before Bolden—inevitable issues arise. (And no, I’m not disputing the fact that African Americans invented jazz and make up the vast majority of its greatest exponents.)

According to Gabbard, “In the first half of the twentieth century, black trumpet masculinity was appropriated by white artists, especially white jazz artists…By re-appropriating and remaking the instrument, black trumpeters inspired white musicians looking for their own means of masculine expression.” And there is more: “White musicians discovered that they could boost their masculine presentation by imitating black men, even by having them close by.”

In effect, white musicians are reduced to sexual and musical vampires, sucking the life-blood out of their hosts. Thus the Original Dixieland Jazz Band, the first jazz group recorded, didn’t play their own music but their “take on black music”; Paul Whiteman is given the obligatory drubbing as “the appropriately named Caucasian who called himself the King of Jazz” (a phrase created by a press agent); and Benny Goodman became popular only by playing Fletcher Henderson’s arrangements (and by the way, Henderson again single-handedly “invented” big band jazz, even though he actually never contributed any arrangements to his own book until Don Redman and Benny Carter left his band). Gabbard fails to mention that the word “jazz” was first applied to white bands; instead he informs us that the word “probably has an African origin.”

Bix Beiderbecke is a perpetual thorn in the side of present day believers in the “jazz-is-black-music” paradigm, and his genius must be consistently downplayed. According to Gabbard, Bix’s playing is “not sensational,” “has no swagger,” and lacks the “grand, dramatic gestures of black artists.” But the cornetist—as revealed in his classic recordings of “Somebody Stole My Gal,” “Goose Pimples,” and Frank Trumbauer’s version of “Riverboat Shuffle,” to name but a few examples—is not only grandly dramatic and sensational, but resounding with swagger (as well as that much undervalued commodity in today’s artistic market: subtlety).

The authoreven claims that “during his short life he was never much of a success,” ignoring the fact that Bix at the peak of his career was prominently featured with the most famous and highest-paying musical organization of his time. Though Beiderbecke spent the bulk of his career playing for dances and later in theaters, Gabbard says “audiences at clubs surely kept right on talking and drinking when he soloed”—again utter, and in my opinion, uninformed speculation.

Beiderbecke intentionally avoided the trumpet, preferring the mellower sound of the cornet, but Gabbard consistently (and annoyingly) refers to him as a trumpeter. And Beiderbecke’s first recordings were from February, 1924, not 1925 as Gabbard states. These recordings feature fully improvised solos even before Armstrong had a chance to do more than merely restate the melody, as he does on “Chimes Blues” and “Riverside Blues” with the Oliver band.

The author also feels compelled to subject Beiderbecke to his by now familiar brand of amateur psychoanalysis. Gabbard relates an incident in which, as a teenager, Beiderbecke was reported to the police after he tried to persuade a five-year-old girl to lift up her skirt. Gabbard writes, “This level of anti-social behavior reveals a deeply troubled young man,” and, without any evidence, concludes, “There is the possibility that he had made sexual advances to other girls as well.” I’m not condoning Bix’s conduct, but Gabbard’s opprobrium sounds more than a little disingenuous coming as it does from someone who has built a career on divining the influence of the penis on American society.

He goes on to describe how Beiderbecke’s parents (also sexually repressed, in the author’s opinion) “ignored his music,” or perhaps had “simply written him out of their lives after his arrest in 1921.” After that time, however, Mrs. Beiderbecke arranged for her son to obtain his first union card, and was quoted in a local newspaper saying how proud she was of his accomplishments. Bix never failed to return home for the holidays and, with the onset of severe health problems, increasingly spent time there.

The story of him finding unopened boxes of his records on one such visit, as dutifully reported in Gabbard’s book, is now widely believed to be untrue because it originated from Esten Spurrier, a friend of Bix’s who held a personal grudge against the family. Bix’s parents felt Spurrier was a potentially bad influence on their son during his recuperation, and barred him from visiting the ailing cornetist at home. (Ironically, an episode involving a musician coming home to discover unopened boxes of records did in fact happen years later when Ornette Coleman visited his mother in Fort Worth, Texas.)

Early in his book, Gabbard lauds Art Farmer, saying his work displays “expertise and power but also a gentleness and a playfulness that transcended the macho self presentation of so many men who are not musicians.” Later he tells us Miles Davis transformed the trumpet with his “expressions of sensitivity and vulnerability.” I would submit that Gabbard could have also learned these musical lessons directly from Beiderbecke, had he been willing and able to appreciate Bix’s artistry free of prejudice.

Many other well-known white (or in the author’s quaint phrase, “pigmentally deprived”) trumpeters and cornetists are treated with similar disdain. Red Nichols, who presided over some of the best jazz recordings of the twenties (featuring Benny Goodman, Jack Teagarden, Gene Krupa, Pee Wee Russell, Adrian Rollini, and other exceptional white musicians of the time), is dismissed as a “minor jazz cornetist who had a hit in 1927 with ‘Ida, Sweet as Apple Cider.’”

And consider Gabbard’s statement that “Louis Armstrong once said that [Bunny] Berigan was his favorite trumpeter among the many white trumpeters who followed in his wake.” The author’s paraphrase misrepresents the full intent of Armstrong’s words. In an interview for Metronomemagazine in 1948, Armstrong was asked to name trumpeters “who play the way Louis likes to play.” The reply, as transcribed by George Simon, was unequivocal and free of any reference to race: “The best of them? That’s easy. It was Bunny [Berigan].” In an article Armstrong himself wrote for DownBeatin 1941, he names Berigan first among his favorite trumpet players for “his tone, soul, technique, sense of phrasing and all. To me, Bunny can’t do no wrong in music.”

Gabbard does praise Maynard Ferguson, but claims he is “best known for his recording of ‘Gonna Fly Now,’ the theme from the 1976 film Rocky.” There is no mention of Ferguson’s ferocious (and racially mixed) big bands of the late 1950s to mid-1960s.

The author also maintains that, “To this day, African American jazz instrumentalists are more likely than whites to deploy a sound that recalls vocal inflections.” Obviously Gabbard is not familiar with the work of Jon-Erik Kellso, who, because he is white, middle-aged, and performs on the mainstream and traditional circuit, exists under the radar of the major jazz press. For my money, Kellso is the greatest exponent of vocalized mute techniques since Cootie Williams, bar none.

Toward the end of the book, the author offers a backhanded compliment to those of his race who are blessed (or cursed) with more musical talent than he evidently has: “The white men who were inspired by black trumpeters like Armstrong unquestionably possess a special breed of masculinity. Any of them could have chosen athletics, the professions, or some other career, but instead they played jazz.”

But would anyone really want Chet Baker to perform surgery on them? Or Tom Harrell to represent them in court? What Gabbard doesn’t seem to realize is that some people have a single-minded passion to pursue one career path above all others despite the obstacles. It has always been difficult to make a full-time profession out of playing jazz, but when racial politics are thrown into the mix, as Gabbard is so eager to do, it can become damn near impossible.

All of this talk about manliness, masculinity, and all their various cognates, creates an obvious problem for Gabbard. What to do about women? He must be careful not to be accused of the “macho self-presentation of so many men who are not musicians.” So he conveniently bypasses the question of why women would be at all desirous of “appropriating black masculinity,” and instead focuses on a predictable round of anecdotes meant to show how female musicians have been victimized at the hands of—you guessed it—those troglodyte white males again.

Gabbard informs us that in 1990, more than 1,400 women were making their living playing the trumpet, trombone, tuba, or French horn. But we cannot view this as a mark of societal progress. Rather, we are told that these professionals, only three of which he consulted, “have always been discouraged from entering a profession that seems too masculine.” A man, it seems, is “profoundly threatened when a woman plays as well as he does.” Moreover, male musicians are stuck in a “boys club mentality,” oblivious to their blatant sexism, and given to acting out unspecified “hazing rituals.”

No evidence is provided outlining the momentous advancements in women’s rights and opportunities throughout the twentieth century—just the same sad litany of male domination. I have no doubt that Gabbard tried to solicit horror stories from the three female subjects he interviewed, but all he could glean were feeble anecdotes about not receiving an invitation to a party, or being vaguely dismissed by Doc Severinsen. (It should be noted that Severinsen stuck by his bass player John Leitham when he underwent a sex-change operation and became Jennifer Leitham—certainly not the M.O. of your typical male chauvinist pig.)

Significantly, none of the women Gabbard consulted mentioned losing any work as a result of their gender. Contrast this with the experience of white trombonist Matt Finders. In New York he was removed from a JVC Festival performance and lost a European tour because “there were too many whites in the band,” as the promoters reluctantly admitted. Later he was hired as the token white musician in the Tonight Showband, where he has remained for the last eighteen years. “It [meaning the color of his skin] finally worked for me,” he noted with irony.

Gabbard also states that white jazz critics have “colluded in writing women out of jazz history.” Apparently this bias is highly selective: Bessie Smith and many other singers are given due credit, as are pianists such as Lil Hardin and Mary Lou Williams. But white writers are “highly suspicious of any female artist who does something other than sing or play the piano.” Exhibits A and B are the trumpeters Valaida Snow and Clora Bryant. Both seem to have had rather successful careers: as the author notes, Snow “appeared in films, toured Europe, and made several recording,” and Bryant also recorded and appeared on the Ed Sullivan show.

But Gabbard’s principal beef is that they have not been appropriately lauded in the jazz literature (though I’m sure they will be soon). The fact is that these two women should be recognized more than trailblazers and anomalies for their time rather than as significant individual voices in jazz. Blue Mitchell, Stu Williamson, Don Fagerquist and even Howard McGhee receive little or no attention in the history books, but all were, in my opinion, masters of the instrument; and Snow and Bryant are just not in the same league. The success of Ingrid Jensen, Anat Cohen, Nicki Parrott, and Terri Lyne Carrington show that any strict notion of what constitutes a “female” instrument has gone the way of the buggy whip. As more and more women study jazz in schools and filter into the profession, we’ll surely see many more attain the highest standards and leave their mark on the music. But I really don’t see how excoriating white males will hasten this inevitable development.

Gabbard has yet more arrows in his quiver directed at his own race. By the author’s account, the artistry of black musicians was “disparaged and even demonized” as a result of the “racism of the day.” Thus he ignores the fact that white audiences have, at least since the 1920s, sustained the careers of all the greatest jazz artists. “In a Southern town like New Orleans, no black musician, no matter how talented, could have the stature of the white musicians who were nevertheless his peers.”

But Louis Armstrong, recalling the funeral for his friend and colleague Henry Zeno, noted “there were as many white people there to pay their last respects for a great drummer man and his comrades.” According to Gabbard, “Most whites preferred ‘sweet’ bands like [Guy] Lombardo’s to the ‘hot’ bands of Henderson and Ellington.” Perhaps, but in the 1920s and 1930s Henderson and Ellington performed almost exclusively at such principally white-only venues as the Club Alabam, Connie’s Inn, Roseland Ballroom, the Grand Terrace, the Kentucky Club, and the Cotton Club.

As for bebop, Gabbard claims, “Although the black beboppers thought of themselves as professionals and not as crowdpleasing entertainers, racist Americans treated them like sharecroppers.” But many white Americans (and Europeans) embraced the new music just as the vast majority of blacks were turning to rhythm and blues. Dizzy Gillespie had nothing but bad memories of his first big band tour for black audiences comprised of “unreconstructed blues lovers down South who couldn’t hear nothing else but blues…they wouldn’t even listen to us.” In Gabbard’s view, even the drug abuse that claimed so many musicians, both black and white, was solely the result of “racism and public neglect.”

An overriding flaw in this book is that, as much as Gabbard wants to talk about “reinventing masculinity,” he seems intent upon reinventing shopworn clichés and stereotypes. He constantly puts forth myths and spurious conventional wisdom as incontrovertible fact, or offers half-baked academic theories. For example: “One school of psychoanalysis has theorized that boys grow up wanting the father’s phallus, the symbol of power. If they are right, then the primal fantasy came true at only one remove for young Louis Armstrong.”

These remarks are prompted simply because Armstrong was given Oliver’s old cornet after his mentor acquired a new one. (The repetition of phallic imagery quickly grows tiresome. The author speaks of Armstrong’s “ability to ‘get it up’ with high notes,” and Dizzy Gillespie’s horn, with its upward pointing bell, “suggest[s] an erection.” Even “advertisements for minstrel shows featuring a caricatured black man holding a banjo out in front of his crotch” are overt references to male genitalia.)

Another dubious theory cited by Gabbard comes from the poet and literature professor Nathaniel Mackey, who contends that scat singing is a form of “telling inarticulacy” and “the result of an ‘unspeakable history’ of racial violence that included lynching and castration.

The inarticulacy represents the singer’s willful dismantling of the gagrule amenities which normally pass for coherence.” It would take a supreme act of will not to hear the humor and high spirits in Armstrong’s scat vocals on “Heebie Jeebies,” “Dinah,” or “Ding Dong Daddy,” to name just a few classic examples. It would also take a stone cold heart not to break into a smile while listening to Ella Fitzgerald’s dazzling displays of vocal aerobatics. And how does Mackey’s theory explain white entertainer Cliff Edwards, better known as Ukulele Ike, recording scat even before Armstrong? Was he “unspeakably” upset at a premonition he might become best known for being the voice of Disney’s Jiminy Cricket?

I am also deeply suspicious of the belief that, in the author’s words, “playing the blues” was a “gesture of resistance” towards “violence and institutionalized racism…Even if blues artists delighted white audiences, the music was a cry of self-affirmation in the face of white racism.” If that were true, why don’t blues lyrics reflect that reality? Some might say that blues artists were too terrorized to speak out directly, but I find this view patronizing. African Americans regularly denounced racism in their own newspapers, and blues records were intended primarily for black audiences.

Black Swan Records—which was black-owned, with the civil rights activist and NAACP founder W. E. B. Du Bois on its board—recorded blues singers, but none decried the evils of racism. Perhaps Maggie Jones’s “Jim Crow Blues” is the exception that proves the rule. Even so, it’s a hopeful song about going up North in search of freedom.

The plain reality is that until the dawn of the civil rights era, the blues and jazz were just not “protest music.” Ken Burns reluctantly discovered this when he sought songs of political indignation for the soundtrack to his PBS jazz documentary. The best songs he could come up with were Bessie Smith’s “Poor Man’s Blues” and Billie Holiday’s “Strange Fruit,” written by the Jewish schoolteacher Abel Meeropol; the other examples were by Josh White, a communist-inspired cabaret performer who wasn’t really a jazz singer at all.

Since close, impartial inspection of data is not Gabbard’s strong suit, his book is riddled with factual errors, some relatively insignificant and others egregious.I don’t want to numb the reader by listing them all, but here are a few notable examples: The book states, “Unlike the characters in films like GreenPastures(1936) and CabinintheSky(1943), black musicians were not caught in a Manichean struggle between the dance hall and the church. Few would have drawn a sharp line between the bawdy music of the one and the sacred songs of the other.”

But as pianist Willie “The Lion” Smith stated, “Back in those early days churchgoing Negro people would not stand for ragtime playing; they considered it to be sinful.” This sentiment is echoed in countless interviews with black musicians active in the first half of the twentieth century.

Gabbard attempts to draw a parallel between developments in jazz and black vaudeville: Bert Williams, who performed in blackface, is held to represent King Oliver’s generation, while Bill Robinson, who never wore blackface, appealed more to Armstrong. “Bert Williams died in 1922,” attests the author, “the same year that Armstrong arrived in Chicago and first saw Robinson. It was truly the end of an era.” But black comedians routinely appeared in blackface when performing for fellow African Americans as late as the 1950s, and the practice subsided only after strenuous urging by the NAACP.

Gabbard claims that King Oliver and Louis Armstrong bonded because they “were dark-skinned blacks in a musical culture where light-skinned Creole musicians took the best paying jobs.” Actually Oliver was a French speaking Creole (hence the name of his Creole Jazz Band).

Regarding Oliver’s famous mute techniques, the author claims Armstrong was “never able to get those same effects.” The truth is that Louis simply preferred the sound of the open horn, but nevertheless displayed muted effects on many accompaniments to blues singers.

Gabbard claims that Armstrong’s reliance on marijuana was “surely another way he asserted his independence in a society that enforced laws against a substance that made him feel less intimidated by racism.” In actuality, Armstrong began smoking marijuana when he struck out on his own as a bandleader, believing it helped calm his nerves. At that time, 1926, the use of marijuana had yet to be criminalized.

Gabbard suggests that Armstrong’s popularity rested on his use of “suggestive lyrics and bawdy humor.” But while such ribaldry may have been on full display backstage, it rarely figured in his performances; Armstrong was a much classier entertainer than that.

Gabbard titles his book “Hotter Than That,” and refers to the tune as written by Louis Armstrong. But the original record label lists Lil Hardin as its composer. I agree that the finished product owes much more to Armstrong than Hardin, but a footnote would have been in order.

The author states that the Miles Davis recording KindofBluecontains no altered chords. However, “Blue in Green,” the third title on the original LP, includes nine in the space of ten bars. This piece, credited to Davis but in fact written by Bill Evans, might rightfully be considered a study in altered chords. Other tracks on the album, such as “All Blues” and “Flamenco Sketches,” likewise contain altered chords.

One of Gabbard’s mantras is that the trumpet is the most difficult of instruments, making it the most “masculine.” He speaks of the “relative effortlessness of the clarinet,” but I see many more good trumpeters around than clarinetists. And what about the French horn, the only orchestral instrument conductors permit to make mistakes in concert?

Playing any instrument at a high level of proficiency is a supreme challenge and a life’s work. And as for the trumpet’s supposedly exalted position in the hierarchy of instruments, we’d all do well to reflect on a widely held attitude that goes back at least as far as Aristotle’s Politics: “Professional musicians we speak of as vulgar people, and indeed we think it not manly to perform music, except when drunk or for fun.”

I can’t leave this book without citing a few examples of what I consider to be utter nonsense:

[Miles] Davis remade jazz a composer’s art.

The trumpeter is an artist who must be in touch with his emotions.

If the trumpeter expressed masculinity in his playing, it is because he is expressing himself in an artful manner.

If a woman like Clora Bryant or Ingrid Jensen rips through a phrase like Armstrong or Gillespie at his most intense, we might say that she is expressing the masculine side of herself. Or we could simply say that she is expressing her feminine side with unusual force.

Such blather tempts me to throw my own horn out the window.

The author’s method of demonstrating the influence of the trumpet on American culture is to dredge up mostly forgettable second- and third-rate books and movies. (One notable exception is Fellini’s La Strada, which is after all an Italian movie, and has nothing whatsoever to do with jazz.) But the music of Louis Armstrong and Miles Davis is among the greatest and most profound artistic achievements in history, and examining Hollywood B-movies or insignificant novels within the same context only serves to diminish this music’s cultural significance. As a professor of cultural studies, I think Gabbard should take a hard look at the culture he comes from: one in which the arduous but noble task of seeking informed and impartial conclusions has been supplanted by a glitzy pursuit of easy acclaim through a zombie-like adherence to fashionable ideologies.

The aim of scholarship now seems too often bound up in formulating a theory first (with the requisite dose of racism and sexism) and then selectively marshaling evidence to support it. It doesn’t matter whether the theory is provable, or even valid or useful. The more sex and violence it contains the better, so as to hold the attention of even the most bored and overindulged college students. (After all, college professors these days have to compete with television and the Internet to make any impact in the classroom.) In turn these students, in their own zombie-like way, will cite these theories as fact in their own work, which is destined to take us further and further away from real experience—which in our case is a true experience of music.

In the course of researching his book, Krin Gabbard received some excellent advice from Indiana University trumpet teacher William Adam: “You must put yourself in the music.” It’s a pity that Gabbard didn’t follow this time-honored wisdom. Instead he chose to grovel at the feet of the most fearsome ideologues in the black (or in his case Africana) studies, women’s studies, and whatever other studies departments; and beg forgiveness for all the real and imagined sins that white males have visited upon the earth (such as that phantom lynch mob out to get Buddy Bolden). Sadly, this craven display of toadyism is what passes for a “presentation of manhood” in too many universities today.

Download Jazz sheet music and transcriptions from our Library.

The Best Of Louis Armstrong

Track List:

00:00 old Kentucky Home 04:35 Drop the Sack 07:27 Panama 11:37 St James Infirmary 16:40 Hot Time in the Old Town Tonight 20:16 Chimes Blues 23:44 Dr.Jazz 26:22 I Ain’t Gonna Give None of My Jelly-Roll 30:28 Jelly Roll Blues 33:19 Frankie and Johnny 37:23 I Want a Big Buter and Egg Man 41:10 Dr.Jazz 52:38 I Ain’t Got Nobody

About the author: Krin Gabbard

Krin Gabbard was born in Charleston, Illinois, in 1948. He now lives in New York city and teaches at Columbia University. His books reflect a lifelong love for both jazz and the movies. While researching the history and making of trumpets for his 2008 book, Hotter Than That, he realized that you’ve got to “blow to know.” He bought himself a trumpet and now plays in a big band on Saturday afternoons. It’s his favorite time of the week.