Robert Fripp, the amazing guitarist (2)

Fripp, the Guitarist

Robert Fripp said in 1986, “Music so wishes to be heard that it sometimes calls on unlikely characters to give it voice.” Fripp was – and is – the opposite of a musician like Mozart, whose seemingly divine, God-given talent enabled him, under his father’s tutelage, to be playing the harpsichord with facility by the age of five and composing sonatas and symphonies by the age of eight.

Of his own natural aptitude, or rather lack thereof, Fripp has often said, “At fifteen, I was tone-deaf with no sense of rhythm, sweating away with a guitar.” (Fricke 1979, 26) He contrasts his situation with that of the supreme guitar hero of his generation: “One might have a very direct, very innate and natural sense of what music is, like Hendrix, or be like me, a guitar player who began music tone deaf and with no sense of rhythm, completely out of touch with it.

For Hendrix the problem was how to refine his particular capacity for expressing what he knew. For me it’s how to get in touch with something that I know is there, but also I’m out of touch with.” (Garbarini 1979, 33)

Little is known publicly about music in the Fripp household and extended family, though he has spoken admiringly of a certain great aunt, Violet Griffiths, a piano and music teacher: “As a young girl she practiced nine hours a day, five on scales alone.” Mrs. Griffiths has been highly successful in inspiring her students; she “regularly has the highest examination results for her pupils.” She attributed her success to “pushing”: “Aim for 100%, not 50%,” (Fripp 1981B, 44) Fripp quotes her as saying.

A similar work ethic permeates Fripp’s own approach to the guitar: what he has been able to accomplish, he feels, has nothing to do with talent, but has been the result of sheer effort. He has practiced guitar with varying degrees of intensity over the years, the most being “twelve hours a day for three days running,” and sometimes six to eight hours a day over fairly long stretches. Such a level of commitment has been necessary to attain the goal: “It’s a question of developing technical facility so that at any moment one can do what one wishes … Guitar playing, in one sense, can be a way of uniting the body with the personality, with the soul and the spirit.” (Rosen 1974, 37-8).

Fripp took up guitar at the age of eleven, playing with difficulty on an acoustic Manguin Frere. Fripp is naturally left-handed, but for some reason decided to go at the guitar in the normal right-handed position, with the left hand doing the fretting and the right hand doing the picking – unlike other famous southpaws like Jimi Hendrix and Paul McCartney, who turned their guitars upside down so they could play them “normally.”

After struggling on his own for some three months, Fripp took lessons for about a year at the School of Music in Corse Mellon, a village a couple of miles from Wimborne, his hometown. His instructor was Kathleen Gartell, a piano teacher who was not a guitarist but who did give him some useful music theory background. The man Fripp has singled out as his most important guitar teacher was Don Strike, whom he called, “a very good player in the Thirties style.”

Fripp’s lessons with Strike lasted about two years, between the ages of thirteen and fifteen. Strike laid the foundation for what was to become one of Fripp’s specialties, a rapid cross-picking technique. A few years later, when Fripp was eighteen, he ran into Strike again; the older guitarist, on hearing Fripp play, shook his hand and acknowledged him the better player. Today Fripp recalls this acknowledgement as an important milestone in his life.

During his teenage years Fripp also experimented briefly with flamenco guitar styles and took lessons from Tony Alton, a Bournemouth guitarist. All such experiences were doubtless helpful in channeling the young Fripp’s musical urges, but he did not feel entirely comfortable with any particular guitar style or discipline: in 1974 he said, “I don’t … feel myself to be a jazz guitarist, a classical guitarist, or a rock guitarist. I don’t feel capable of playing in any of these idioms, which is why I felt it necessary to create, if you like, my own idiom.” necessary to create, if you like, my own idiom.” (Rosen 1974, 18).

Fripp’s first electric guitar, purchased when he was about fourteen, was a Hofner President, which he played through a six-watt amplifier with an eight-inch speaker. He has also used Fender Stratocasters, a J-45 acoustic, a Yamaha acoustic, a Milner pre-war acoustic, and a Gibson tenor guitar. The main instrument with which he was associated in the 1970s was the Gibson Les Paul, a guitar he found ideal for his characteristic single-string work. In the 1980s he used Roland synthesizer guitars (notably with King Crimson IV and in his collaborations with Andy Summers).

Recently, with Guitar Craft, he has championed the Ovation Legend 1867 super-shallow-bodied acoustic. (Technically inclined readers who are interested in more details on Robert Fripp’s equipment – amplifiers, picks, strings, devices, and so on – are urged to consult Rosen 1974, 32; Mulhern 1986, 90; Drozdowski 1989, 32; and the liner notes to several of the albums.).

Almost from the very beginning of his guitar playing, Fripp realized that “the plectrum guitar [guitar played with a pick] is a hybrid system” for which no one had ever developed an adequate pedagogical method. Left-hand position and fretting technique, at least for the nylon-stringed guitar, had been established to a high degree of sophistication by classical guitarists, but right-hand position and plectrum technique had no comparable tradition. The use of a pick is derived from the playing of banjos and subsequently guitars in the jazz of the 1920s and 1930s, but every player essentially developed his or her own method; and since in the jazz context “the main function of the right hand was to enable the guitar to be heard above ten other pieces in a dance band,” the results generally lacked for subtlety.

“So there I was at twelve in 1958 and it was so obvious that there was no codified approach for the right hand for the plectrum method. So I had to begin to figure it out … It was very difficult because the only authority I could ever offer was my own.” Beginning then, Fripp devoted nearly thirty years to the development of the picking method he now teaches to his Guitar Craft students. Part of the development took place on a conscious level, but much of it was a sort of unconscious accretion of physical knowledge gained through constant practicing. Fripp says that when he came to consolidate the approach for Guitar Craft, “There was a knowing in the hand through doing it for years which I consulted. It’s interesting. My body knew what was involved, but I didn’t know about it.” (All quotations in this paragraph from Drozdowski 1989, 30).

Fripp’s view is that educating oneself musically is a never-ending process. From a technical point of view, his approach seems to involve systematically attacking theoretical entities like scales through the physical and mental discipline of learning to play them fluently. In rock music, he points out, only three or four scales are in common use – Major, Minor, Pentatonic (Blues), and slight variants of these.

But in fact, any number of other scale formations are available to the creative musician, ranging from the old Church Modes through the so-called synthetic scales (which have exotic names like Super Locrian, Oriental, Double Harmonic, Hungarian Minor, Overtone, Enigmatic, Eight-Tone Spanish, and so on, and on into symmetrical scales (what twentieth-century French composer and teacher Olivier Messiaen called the “Modes of Limited Transposition”) such as Whole Tone, Chromatic, and Octatonic/Diminished.

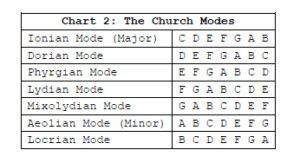

All of these can be learnt in various transpositions, that is, starting the scale on a different note (C Major, C# Major, D Major … B Major). In addition, most of these scales can be used as the source of other formations by changing the tonic note while retaining the pitch-set itself. Such was the basis of Western European medieval and Renaissance modal theory – a theory in which one basic scale (the diatonic scale, corresponding to the white notes of the keyboard) ultimately served as the basis of seven different modes, each of which was felt to have its own unique psychological and symbolic character:

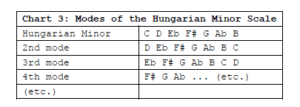

Today’s enterprising musician may likewise construct “modes” based on some exotic (non-diatonic) scale, yielding still more inflections or tonal dialects, still more musical variety. For instance, the modes based on the Hungarian Minor scale would begin like this:

A further avenue of scalar exploration, which, so far as I know, Fripp has never mentioned in print nor worked with himself, is the raga system of India, with its rigorously logical array of seventy-two parent scales. The point of all this is that each individual scale carries with it certain musical characteristics, certain expressive possibilities, certain objective sound-qualities available to all who master them. Western classical music got along quite nicely for some two hundred years (let’s say 1650-1850, using essentially only two scale forms, major and minor; much twentieth-century art music has concentrated on a single form, the chromatic or twelve-tone scale.

Fripp has been eager to move into new territory: specific sources of unusual scales he has cited as having been useful to him include Bartok string quartets, Vincent Persichetti’s staid but readable textbook compendium of contemporary musical language, Twentieth-Century Harmony, the eccentric yet influential Joseph Schillinger System of Musical Composition, and jazz-rock groups of the 1970s such as the Mahavishnu Orchestra and Weather Report. (Fripp 1982A, 102) Fripp sums up: “The possibilities for extending [musical, scale] vocabulary are … quite immense. Since it takes three or four years to be able to work within any one scale fluently and utterly, there’s more than enough work for a lifetime.” (Garbarini 1979, 33)

King Crimson – Islands

Paradoxes of Process and Performance

From the foregoing discussion, the reader might get the impression that the technical side of music is all-consuming for Fripp. To the contrary, it is eminently clear that he views the discipline of guitar technique, scales, and so on, not as an end in itself but merely as a means to an end. The end, to put it simply, is to make contact with music. And to make contact with music involves work on the whole personality, a process which has social, cultural, and political ramifications; art and life cannot be separated. Although Fripp’s most developed ideas on the subject of making contact with music have been expressed in terms of his Guitar Craft teaching, and are best discussed in that context, here I might attempt a brief summary of the concept of “music” that has motivated Fripp since before the earliest days of King Crimson.

In talking, thinking, writing, and reading about music as an ultimate quality – for “Music,” as Fripp has written, “is a quality organized in sound” (GC Monograph One [A], VI: see note in hard copy for actual genesis of this quotation) – it must of course always be borne in mind that we are attempting to deal with the ineffable through the medium of language, with all its limitations. Prose has its own laws and grammars, having evolved, one might say, not in order to describe or explain the ineffable, but rather to convey information of a more mundane nature.

Music, conversely, has evolved as a subtle language of the emotions – or, if you prefer (and Fripp probably would), a language of the spirit. Poetry recited aloud, with its quasi-musical cadences, meter, rhythm, pitch, and vocal tone colors, is somewhere in between. The point is that words can never convey the meaning of music; often enough, verbal formulations of the ineffable bog down in paradox, antinomy, self-contradiction. This will happen in this book, and it has happened to Fripp from time to time.

In 1973 Fripp said, “I’m not really interested in music. Music is just a means of creating a magical state.” (Crowe 1973, 22) What he meant (I think) by this was that the outer forms of music, its styles, history, structure, even aesthetics – the stuff of the academic approach to music – were not the point for him. The point was the “magical state” that the practice of music could put one in. Seen from this vantage point, the actual notes and rhythms, the timbral surface, the sounds in themselves, hardly make any difference; it is the attitude and receptivity of the participants that matter. The focus is not on the object, but on the subject – not the sound, but the listener.

Not the knowledge, but the knowing. Paradoxically, of course, it is precisely the sounds you hear, whether you are the musician or the audience, that will enable you to draw your attention to the quality of the knowing: the sounds become the knowledge, but it is the knowing rather than the knowledge that is vital.

In 1974, Fripp told an interviewer: “When I was twenty-one I realized that I’d never really listened to music or been interested in it particularly. I began to take an interest in it, as opposed to being a guitar player who worked in certain situations. I’ve gotten to the point now where I see music as being something other than what most people see. I would say that the crux of my life is the creation of harmony, and music you take to be one of the components of that harmony.” (Rosen 1974, 38)

This statement seems related to the earlier one, but here the word “music” is used in a different sense. Here “m

usic” signifies that intuitively grasped quality, organized in sound, which constitutes the “knowing” of the true musical experience. What Fripp is saying here (I think) is that he had been a guitarist for about ten years before realizing that there was a sense behind the sounds he had been producing. Previously, he had worked on music purely as a craft, as a physical skill on a mechanical level, like a typist whose fingers fly about the keyboard without any recognition of the meaning or import of what’s being typed, or like a conservatory music student who practices for hours a day, never paying attention with his ears to the music there. And, in a sense, music isn’t there if no one is listening to it as such; there may be organized sound, but not a quality organized in sound. In this quotation, Fripp uses the visual analogy: “I see music as being something other than what most people see.” Not the seen, but the seeing.

articularly during the Frippertronics tour, Fripp would invite his audiences to become part of the creative process by engaging in active listening. When the audience expects the performer to do everything for them, the result is passive entertainment, diversion, escapism. When the audience participates sensitively in the creation of the music – for the real music is not “out there” somewhere, existing as an object, but “in here,” in the quality of attention brought to the mere sounds – then the result is art. At a Boston concert, Fripp told the audience, “You have every bit of the responsibility that I have. Because life is ironical, I get paid for it and you don’t.” (Schruers 1979, 16)

The central paradox, or quandary, of Fripp’s entire career has revolved around the difference between, on the one hand, making art-objects for a product-hungry yet passive audience, and, on the other hand, actually making art with an audience on the basis of a vision of a shared creative goal. Like making love, to make art you need equal partners; otherwise one or the other of the partners becomes a mere art, or sex -object for the other. Fripp may have had such thoughts on his mind when, in 1982, he remarked bittersweetly that in swinging London in 1969, “I began to see how much hookers, strippers and musicians have in common: they sell something very close to themselves to the public.” (Fripp 1982A, 42) Once one has tasted real love (or real art), mere sex (or mere entertainment) may satisfy on a certain primitive level, but a deeper longing remains frustrated.

Fripp saw King Crimson as a way of doing things, and though he never defined very precisely what he meant, I imagine one thing he had in mind was this idea of making music with fellow musicians on the basis of a shared intuitive experience of music as a quality organized in sound – and then taking that experience to the public in hopes of expanding the circle of sharing in the creation of art. King Crimson, Fripp always stressed, was primarily a live band, not a recording unit.

Ultimately, Fripp has concluded that recordings cannot convey a quality experience of music, and for this reason has very mixed feelings about his entire recorded output. An interviewer asked him recently, “Do you still think of making records as a bother and a burden?” Fripp answered: “Sure … Because it has very little to do with music. See, the end to music is a process. The end to recording is also a process. But a record is a product. Because of the restrictions and constrictions, the way of recording … it’s very difficult for that process to be reflected in the product.” (Drozdowski 1989, 37)

Nearly a decade earlier, Fripp had expressed the same frustration, in the context of producing an album for the Roches. “Translating from performance to record,” he wrote, is something like trying to put “Goethe into English or Shakespeare into German” and trying to express “the implicit rather than the literal sense.” (Fripp 1980A, 26)

Using a variety of images and metaphors, some of them religious, many musicians, irrespective of genre, have said that the key to creativity lies, in effect, in getting the ego out of the way and allowing a greater force to play through them. Felix Cavaliere: “We are like beacons from another source … I feel some of us as human beings are tuners to this vibration that comes through us.” Lamont Dozier: “I can’t take credit for this stuff. I’m only human and these things are the makings of God. Everything I do that’s good, at least, is a reflection of His hand.” Judy Collins: “Everybody’s a channeler. Every artist who walked down the street and whistled a tune

s a channeler. We don’t do it. It comes through us. It’s not ours.” Raffi: “I find the process of where these songs come from mysterious, because … I feel that, sure, I can take credit for these songs, but they come from another place.” (Song Talk 1989)

Robert Fripp’s formulation of the principle goes like this: “The creative musician … is … the radio receiver, not the broadcasting station. His personal discipline is to improve the quality of the components, the transistors, the speakers, the alloys in the receiver itself, but never to concern himself overmuch with putting out the program. The program is there; all he has to do is receive it as far as possible.” (Garbarini 1979, 31-2)

Fripp the Listener

When I was fourteen years old there was rock’n’roll – Fats Domino and Bill Haley – but frankly I thought it was stupid. I didn’t like rock’n’roll. I was a snob and I still am. I think rock n roll is interesting and some of it is more interesting than it used to be in the fifties. Yet basically it’s not something that means very much to me. If the whole history of rock’n’roll disappeared tomorrow morning, I wouldn’t care. I’m delighted that I’ve influenced rock’n’roll musicians. I’m pleased that David Bowie has said nice things about me and so has Brian Eno. Outside of [their] being complimentary, the only thing I admire about rock’n’roll [musicians] is how much money they make.

– Steve Reich (Vorda 1989, 16)

One of the ideas that was important to me was that you could be a rock musician without censoring your intelligence. Rock music has a very anti-intellectual stance, and I didn’t see why I should act dumb in order to be a rock musician. Rock is the most malleable musical form we have. Within the rock framework you can play jazz, classical, trance music, Urubu drumming. Anything you like can come under the banner of rock. It’s a remarkable musical form …

– Robert Fripp (Grabel 1982, 22)

The Agony of Rock

The war of words over rock goes on – telling us, if nothing else, that music is still alive, and that people (some people, anyway) care deeply enough about it to take a stand one way or the other.

Critics have often contended that Robert Fripp’s guitar concepts of the late 1970s and 1980s – you can hear them in Frippertronics as well as the League of Gentlemen, King Crimson IV, and Guitar Craft – owe a debt to the minimalist tradition of Steve Reich, Philip Glass, La Monte Young, and Terry Riley – a tradition that began in the 1960s as a rebellion against the academic serial music of the 1940s and 1950s. From its beginnings, minimalism seemed to have something in common with rock: a steady pulse, plenty of repetition, a grounding in simple tonality. Furthermore, the audiences for both types of music overlapped to a considerable extent. Albums like Riley’s A Rainbow in Curved Air (1969) were packaged psychedelically and marketed to the rock public; many of Philip Glass’s early performances took place not in classical concert halls but in downtown New York rock clubs.

The 1970s saw a parting of the ways, however. The music of the best minimalist composers grew more complex, more difficult – in a sense, more classical and less minimal. With a few notable exceptions, such as Brian Eno, rock musicians, after some flirtations with minimalism’s intellectual base, drew back into mainstream rock styles.

Fripp himself has denied that Reich had any direct influence on his work; when he made No Pussyfooting with Brian Eno in 1972, an album often cited as one of the crucial minimalism-rock connections, Fripp had heard neither the music of Reich nor of Glass (though Eno had). Later, Fripp got to know Reich’s work and said he enjoyed it, but only to a degree: “It takes me to a point at which something really interesting could happen, but doesn’t quite make that jump.

Because it is preconceived and orchestrated. What I should personally like to do is to add the random factor, the factor of hazard, to what he’s doing, to walk on stage unexpectedly during one of his performances and having become familiar with the tonal center, improvise over the top of it.” (Garbarini 1979, 32)

The “factor of hazard” is to Fripp an important criterion for judging the effectiveness of music. In the previous chapter we discussed his dissatisfaction with making records: the human factor of interaction between musicians and audience, the creative process, the “way of doing things,” the factor of hazard, are difficult if not impossible to capture on recordings. For similar reasons, he has repeatedly remarked that he is “not really a record listener.” (Watts 1980, 22) Fripp says, “For me, music is the performance of music,” while allowing that “of course, if you don’t go to Bulgaria very much, the best way for you to hear a Bulgarian women’s choir is on record.” (Drozdowski 1989, 36)

Pundits have debated for years the difference between popular music and art music. Fripp doesn’t use the word “art” much, but he has voiced a down-to-earth distinction between what he calls “popular culture” and “mass culture”: “Popular culture is when it’s very, very good and everyone knows it and goes ‘yeah!’ Mass culture is when it’s very, very bad and we all know it and we go ‘yeah!’ Mass culture works on like and dislike, and popular culture addresses the creature we aspire to be. Examples of popular culture: Beatles, Dylan, Hendrix.”

Although critical of mass culture from what might be called an aesthetic point of view, Fripp does not dismiss it entirely. He feels that under certain circumstances mass culture can be used for the good, citing the Live Aid concert in England – an event which awakened in people a genuine spirit of caring and generosity, regardless of cynical questions that were raised regarding how well the money was used and how much help the fund-raising actually did. (Drozdowski 1989, 34)

As noted in this chapter’s epigraph, Fripp sees rock music as “the most malleable musical form we have.” In my book on Brian Eno I defined rock as a specific set of musical style norms (involving certain song forms and rhythmic patterns, certain types of instrumentation and vocal delivery, and so on), in order to show how some rock musicians have gone “beyond rock” into other, new, hybrid musical genres of their own creation.

While viewing rock as a musical style complex is interesting enough as an exercise in analytical musicology, in the real world rock is more a spirit than a style, more an audience than a specific type of music. For the sociologist, rock is a demographic bulge; for the record industry, rock is a marketing category, a publicity strategy. Fripp has said, “One can, under the general banner of rock music, play in fact any kind of music whatsoever.” (Garbarini 1979, 32) I would add only that rock seems to move in cycles – periods of creative diversity followed by periods of stagnation, and that one problem for many musicians is getting their creative music accepted as “rock” by the music industry during periods of industry stagnation.

For Fripp, rock is a democratic music. Although a masterful guitar technician himself, and although he pushes his students to develop their musicianship to the utmost, he acknowledges that in rock, ideas count more than musical competence, sincerity more than virtuosity: virtually anybody who feels the urge can make a musical statement in the language and context of rock, regardless of how well, in classical terms, they can play or sing. The voices of Bob Dylan and Bruce Springsteen, coarse and “untrained” enough to send classical purists into fits of derision, became the voices of whole generations. Eno, though perhaps an extreme case, was so unskilled at playing guitar and keyboard that he called himself a “non-musician.”

For Fripp, “rock is an immediate expression of something very direct. Rock and roll is therapy on the street, it’s available to everyone. Rock and roll is street poetry. It can also be more sophisticated, but it needn’t be.” (Garbarini 1979, 33) For Fripp, “a rock’n’roll audience is always far, far better than any, because they’re instinctive, they’re on their feet, and they can cut through the pretensions of the performer very quickly.” (Drozdowski 1989, 30)

As for stylistic qualities, the rhythm or beat of rock – its most salient and consistent musical characteristic, the thing that rock’s initiates ecstatically extol while its detractors daintily denigrate – represents to Fripp positive sexual energy, “energy from the waist down.” By contrast, developmental harmony – a musical development peculiar to the Western world, and a self-conscious feature of its music really only since the Renaissance – represents to Fripp an intellectual process belonging to the province of the mind. (Watts 1980, 22) Since his earliest music with King Crimson, Fripp has been interested in combining these two sources of energy, the physical and the mental, rhythm and harmony – making, as well as speaking out on behalf of, rock music that could “appeal to the head as well as the foot.” (Garbarini 1979, 31)

Fripp came to believe, however, that many of the progressive rock groups of the early 1970s were not so much intrigued with the intangible spirit of King Crimson – that special way of listening, of doing things, of making music – as they were intent on aping Crimson’s outer musical vocabulary: the virtuosic musicianship, the epic, extended forms, the exotic harmonies, the quasi-mystical, mythological lyrics, the wide variety of instrumental sound colors.

Full-blown Gothic rock was a genre for which Fripp had absolutely no use. Declared a majestically scornful Fripp to John Rockwell of the New York Times in 1978: “I don’t wish to listen to the philosophical meanderings of some English half-wit who is circumnavigating some inessential point of experience in his life.” (Rockwell 1978, 16) Fripp’s rhetorical attack on the movement he’d helped create continued in his own column in Musician, Player, and Listener in the early 1980s, ridiculing “enthusiastic art-rock space cadets whose sudden success seemed to validate pretensions on all levels; they huddled in unholy quorum with pliant engineers to generate excess everywhere.” (Fripp 1980A, 26)

Fripp’s critique of 1970s rock extended to jabs at the stars who had let themselves get fat: in his view, they “became more interested in country houses and riding in limousines, expensive personal habits and all that. The rock musicians who were public figures in the 70’s copped out, and now we have cynicism towards our public figures that is wholly justified.” (Grabel 1982, 58)

Fripp related a story in 1979 that indicated the depths of his disillusionment with the rock fantasy. In August 1975, when King Crimson III had been defunct for a year, Fripp having broken it up at least in part because of the impossible contradictions he had been trying to reconcile between his concept of music and the conditions imposed by rock industry realities, he went to hear a rock show at the Reading Festival: “We’d been waiting an hour and a half while their laser show was being set up. I went out to the front.

It began to rain. I was standing in six inches of mud. It was drizzling. A man over here on my right began to vomit. A man over here to my left pulled open his flies and began to urinate over my leg. Behind me there were some 50,000 people who maybe for two or three evenings a week, for amusement, for recreation, would participate in this imaginary world of rock’n’roll. Then I looked at the group on stage – their lasers shooting off ineffectually into the night, locked into this same dream. Except they’re in it for twenty-four hours a day, seven days a week for the rest of their lives.” (Jones 1979A, 20)

Robert Fripp has felt the agonizing paradox of rock: on the one hand, the possibility of a real magic synthesis, the merging of body/soul/rhythm and mind/spirit/harmony, the seemingly infinite malleability of the basic forms, the potential for direct communication between artists who are passionately committed to ideas and an audience that cuts through artistic pretension and snobbery; on the other hand, the reality of rock as escapist entertainment, the greed, the homogenization of taste through the corporate structure of the recording and radio industries, the tendency to aim for the lowest common denominator of mass culture, the meaningless repetition of formulas, the very unhealthiness of the typical rock lifestyle itself: the star syndrome, the drugs, the pointlessness of wasted talents and lives.

Both punk/new wave and disco, those musical explosions of the mid-1970s that so many felt to be diametrically opposed to each other, Fripp felt as a breath of fresh air. Both seemed to him to be music of the people, to return music to the people, throwing the dinosaurs of the music industry off track, however temporarily.

The raw energy of punk had been prefigured by the aggressive intellectual heavy metal sound of King Crimson III – and even earlier by the intense negative energy and profound frustration that bursts through King Crimson I songs like “21st Century Schizoid Man.” Fripp said, “When I heard punk I thought, I’ve been waiting six years for this.” (Grabel 1979, 32) As for disco, Fripp called it “a political movement that votes with its feet. It started out as the expression of two disadvantaged communities – the gays and the blacks.” As a vital form of social expression, Fripp viewed disco as “nihilistic, but passively nihilistic,” a movement that simply ignored the traditional social framework outside its boundaries. (Schruers 1979, 16)

Robert Fripp believes that one can learn just as much by listening to music one dislikes as by listening to music one likes – in other words, that there can be an educational purpose served by music beyond that of satisfying mere subjective taste. “I go and see people who I don’t like because I get something from it which is worth far more than having been entertained.” (Watts 1980, 22) Rock writer Michael Watts characterizes this view as “puritanical”; puritanical or not, it is consistent with Fripp’s view that the quality of attention one brings to the experience of music is more decisive than the quality of the musical sounds in themselves. Not the sounds, but the listening.

Many of the musicians Fripp has mentioned in interviews over the years are jazz or jazz-rock players – Ornette Coleman, Charlie Parker, Miles Davis, Tony Williams, Frank Zappa. One name that pops up repeatedly is Jimi Hendrix, whom Fripp cites as an example of pure embodiment of the spirit of music. The intensity of the musical current flowing through Hendrix is what killed him in the end, according to Fripp. Hendrix’s guitar technique itself, however, “was inefficient and, as an example, misled many young guitarists.” (Fripp 1975)

It seems Fripp has never been able to muster much enthusiasm for listening to guitarists for the sake of listening to guitarists. He has peevishly and somewhat inscrutably characterized his chosen tool as “a pretty feeble instrument.” Post-Mayall-Bluesbreakers Eric Clapton he found “quite banal,” while Jeff Beck he could “appreciate as good fun.” (Rosen 1974, 18) Of the entire 1970s and 1980s crop of rock guitarists, Fripp has said little; indeed he hasn’t appeared particularly interested. The whole rush to synthesizer guitars, MIDI, and digital signal processing in the 1980s left Fripp unimpressed.

He did use the technology for his own purposes in King Crimson IV and with Andy Summers, even deigning to endorse the GR-300 synthesizer guitar in Roland advertisements in 1982. But he is not especially thrilled with new sounds for the sake of new sounds, particularly if the new sounds are merely poor imitations of old sounds: “Why would a world-class guitar player [playing a guitar synthesizer] settle for sounding like a third-rate saxophone player, and then a trumpet player and then a synthesizer player?” (Drozdowski 1989, 36)

Taking on the Classics

Some of Fripp’s most perplexing comments on other music concern the Western art music tradition. On the one hand, the music of some of that tradition’s masters has figured prominently in Fripp’s own musical self-education.

He has often acknowledged his debt to Bartok, particularly the Bartok of the String Quartets, many of whose movements sound positively Frippian, with their intense linear counterpoint, percussive rhythms, odd metrical schemes, extended tonality, exotic scales, and piquant dissonances. Stravinsky’s name comes up from time to time, as when Fripp mentioned the Russian in a discussion of tuning, temperament, and enharmonic pitch notation (Mulhern 1986, 99); on another occasion he called early Stravinsky “really hot stuff.” (Garbarini 1979, 32) Fripp expressed admiration for Handel, Bach, Mozart, and Verdi in a 1980 essay, but he was not focussing on their music so much as he was making the point that these composers had had to teach themselves how to thrive creatively while working in “very difficult political and economic conditions … Surely the most surprising point is how much inspired work had prosaic origins.” (Fripp 1980G, 30)

On the other hand, Fripp’s assessment of the classical tradition as a living, functional organism is not particularly generous. His collaborator Eno has been blunt about it: “Classical music is a dead fish.” (Doerschuk 1989, 95) Fripp is more restrained, but has expressed major reservations about the classical orchestra’s viability as a source of a quality musical experience for the musicians – and hence for the audience. As a form of musical organization, Fripp has called the classical orchestra a “dinosaur” – gigantic, lumbering, possessing little discerning intelligence, and overdue for extinction. Although he can respect the discipline of orchestra life and musicianship, Fripp himself “would find it very frustrating” to be an orchestral player: “How awful that the only person who is expressing himself is the composer, with the conductor as the chief of police and the musicians as sequencers … It’s stuck.

There is a cap on how far it can go. There is a cap on what it can do.” And then Fripp moves on to his own agenda: “Within the league of crafty guitarists … the aim is not to follow any one person but to be sensitive to the group as a whole and respond to the group as a whole.” (Mulhern 1986, 96)

According to Fripp, Beethoven was undoubtedly one of the “Great Masters,” with direct access to music at its creative source. But listening to Beethoven’s music today, “transcribed through two hundred years of interpretation and analysis and a sixty piece orchestra with an intelligent conductor”, is for Fripp an indirect, incomplete experience. He would much rather have been present to hear Beethoven improvise at the piano in person. “My personal reaction listening to the [Beethoven] String Quartets is not the sense of passion that was obviously present at the moment when it came through. Rather I feel a sense of how remarkably intelligent it is, but I don’t get that direct touch that I’m sure Beethoven had, which I’ve had from the rock band Television.” (Garbarini 1979, 32)

The Guitar Craft repertoire is by and large learned by rote and performed from memory. One afternoon in February 1986 Fripp and a bunch of his students were standing around the coffee urn during a Guitar Craft seminar discussing the pros and cons of notated music. Fripp’s final word on the topic was, “I’d much rather have a date with my girlfriend than get a letter from her.” It appears he won’t budge from his basic position, which is that the process of playing from notation inevitably takes music “further and further away from the original moment of conception.” (Garbarini 1979, 32)

This position is congruent with Fripp’s professed mistrust of written media and recorded sound – perhaps strange for someone who has put out so many records and published so many articles, and is consistent with his insistence that the highest form of musical experience can take place only in a situation of direct human contact. To musicians who have tasted the rewards of a close, devoted study of masters like Bach, Beethoven, and Mozart – through live performances, keyboard score-reading, recorded media, and the process of intuitive analysis – this is a tough pill to swallow.

A parallel might be drawn between reading a Bach score and reading the Bible. Moses’ or Jesus’ impact was undoubtedly most intensely felt in person – just as to hear Bach improvise a fugue on the organ or harpsichord must have been an awe-inspiring experience, at least to those present with the ears to hear and the musical preparation to understand what was happening. Yet without notation, Bach’s fugues, which through writing out he was able to refine to high levels of perfection, would be lost to history. I for one am glad to have the Bible and the Well-Tempered Clavier on my shelf.

Of course, whenever you have spiritual or musical masters around whom a written tradition accrues, you inevitably have latter-day disciples of all colors and stripes who battle among themselves to claim the “true” interpretation, or, worse, believe that salvation lies somehow in the written documents themselves rather than in direct personal contact with the source. Perhaps, like a modern musical Martin Luther, Fripp is saying that we can all have direct contact with music through faith and effort, that to speak directly with God we don’t need all the accumulated ritual, regulation, and written tradition, that arguing for the inherent superiority of the written art music canon is something like arguing in the manner of contemporary Christian fundamentalists in favor of the doctrine of Biblical inerrancy at the expense of unmediated personal faith.

Classical musicians play notes that are written and fixed on paper. Guitar Craft performances consist of music that appears to be carefully composed and tightly disciplined, as if the musicians are simply doing their best to execute some sort of pre-conceived composition. But in theory, or in the ideal, there is an element of improvisation in both classical and Guitar Craft performances: according to Fripp, the guitarists “can play any note they like provided it’s the right one”. (Drozdowski 1989, 30) It seems to me that in any kind of musical performance situation there will always be a danger of the musician falling into unconsciousness, relying on technique alone, and becoming in effect a sound-producing automaton.

In order to place Fripp’s approach in perspective, perhaps a bit of historical background would be helpful. The Western art music tradition has a rich history of performers taking all kinds of liberties with the written score, in many instances in effect completely re-composing it, whether in actual notation or in the heat of an inspired performance. Many composers have also been improvisers, able to develop and transform themes into new creations on the spot. It was really only with the rise of positivist musicology in the twentieth century that this sort of thing went out of favor and that improvisation, in the art-music world, became a lost art. Nowadays, indeed, the original composer’s “intentions” are widely held to be primary and inviolable, and the best performances are commonly deemed to be those most closely in accord with those sacrosanct intentions.

In the twentieth century, positivist musicologists have industriously cleaned up the music of the masters, assiduously sweeping out all the editorial additions that had crept in through the nineteenth century, getting back to the composers’ manuscripts and first published editions in order to take a new, refreshed look at the music in its original form (though often enough, with composers’ revisions, discrepancies between sources, and so on, reconstructing the “original” score can be a bit of a headache, to the point that doubt may be cast on the very concept of a single “original score” or Urtext). This cleaning-up was a first step; the second stage, now in full swing, is the movement toward faithful reproduction of historically authentic performance practices involving the use of period instruments, original scores, and all the knowledge of style, ornamentation, improvisation, and so on, that musicology can manage to dig up.

In the contemporary historical performance scene, opportunities for whole new ranges of use and abuse of knowledge have opened up. On the one hand, the educated musician can respond to the situation by contacting the spirit behind the music and – not slavishly but with considered knowledge – playing with a range of embellishments and other expressive elements (tempo, dynamics, phrasing, and so on) not literally specified by the raw notes in the score but called for by the spirit of the music, internalized in the sensitive performer through study and practice.

On the other hand, the historical performance movement is all too full of musicians and academic authorities squabbling over obscure details of musical praxis, not unlike scholastic medieval theologians squabbling over the “correct” interpretation of a verse of Scripture.

The music of every historical period calls for different kinds of interpretation, and it is probably true that there is more freedom in interpreting the music of the eighteenth century and earlier than nineteenth- and twentieth-century music, since in recent times composers have become more and more meticulous in notating their intentions with regard to every last nuance of expression.

Be this as it may, surely one can speak of a range of possible interpretations of a given piece of classical music; when all that is played is the notes, with no hint of internalization of the style, of the music – such playing is (and has always been, I suppose) the bane of music departments and performance spaces around the world. But assuming cultivated sensitivity and intuitive musicality on the classical player’s part, performance of the traditional repertoire can surely approach Fripp’s ideal of a music where one can play any note one likes “provided it’s the right one.”

One thorny problem for classical musicians is that it’s just so awfully difficult to “improve” on what Bach, Mozart, and the lot wrote down on paper. To anyone who has not fully fathomed such composers’ consummate mastery nor directly felt the complex yet elegant system of emotional and structural checks and balances built into the interrelationships among even the smallest details in such music, this is probably impossible to explain.

With the possible exception of free-form avant-garde jazz, all music that I know of has a “program” of some sort, that is, a tacit or explicit set of conventions and directions to be followed; the paradox is that the sensitivity and meaningfulness of the performance increases in proportion to the degree the musician surrenders the ego to the will of the music itself.

This is as true of the King Crimson or Guitar Craft repertoire as it is of the classical. And it is no different even in most forms of “free” improvisation – the musician is not starting in a vacuum but, with the technique at his or her disposal, is drawing on his or her total knowledge of music (scales, theory, harmony, sense of rhythm, sense of continuity, principles of unity and contrast, and so on). Music plays through the performer, conditioned in a sense by the performer’s individual knowledge, experience, taste, and talent, but (in those rare moments) transcending such limitations and manifesting itself as Music in a pure state.

We have already noted Fripp’s lament, “How awful that the only person who is expressing himself [in classical orchestral music] is the composer.” Fripp has also said, “Whenever a musician is interested in self-expression you know it’s gonna suck.” (Drozdowski 1989, 30) Does anyone except myself sense yet another paradox lurking shadow-like in these two statements? Chew them over for a while; we will return to them in the final chapter.

Browse in the Library:

Or browse in the categories menus & download the Library Catalog PDF: