The Creative Development of J.S. Bach (and Vol. 2) 1717-1750 Sheet Music Library

- The Creative Development of J.S. Bach (Vol. 2) 1717-1750 Sheet Music Library

- Introduction

- The Well-Tempered Clavier I and other keyboard works

- Prelude, fugue, and invention

- J.S. Bach, The Well-Tempered Clavier, Book 1 / Sviatoslav Richter ( 1969 )

- Download and Read the full book: The Creative Development of J.S. Bach (Vol. 2)

Introduction

In Prince Leopold of Anhalt-Cöthen Bach seems to have found in many ways the ideal patron. The prince was not only a good bass singer but also played the violin, viola da gamba, and harpsichord. And in 1713, after his return from a grand tour during which he acquired published copies of much French and Italian music, he took advantage of the dissolution of the Berlin court Capelle under Friedrich Wilhelm I by employing six musicians (and later a seventh) who had been made redundant. By late 1717, when Bach took up his appointment as Capellmeister, Leopold had increased the number of musicians at the Cöthen court to sixteen, of whom about half were players of the front rank.

There were disadvantages for Bach at Cöthen, however. Since it was a Calvinist court, there was no opera—such an enterprise, had it existed, could hardly fail to have attracted Bach’s interest. Furthermore, the Calvinism of the ruling prince meant that there was no regular opportunity for Bach to compose and perform church music, though he did so at least once for the prince’s birthday1 and might have done occasionally at the Lutheran Agnuskirche, which Bach and his family attended.2 As for secular vocal music, one of Bach’s regular duties was to perform a cantata every year for the prince’s birthday and another for New Year’s Day, though very few of these works survive.

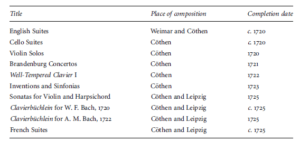

In the field of instrumental music Bach’s situation was considerably more advanta-geous. In moving from Weimar to Cöthen he had risen from the second-rank post of Concertmeister to the top-rank post of Capellmeister. And as such he directed an instrumental ensemble that few German courts could rival. In addition, the reigning prince was clearly passionate about music and no doubt gave his brilliant Capellmeister all the support he needed. In this favorable atmosphere Bach was able to compose some of his greatest keyboard and instrumental music, much of it never to be exceeded in later years:

The place of composition shows that there were overlaps at both ends of the Cöthen period. Only the first of the English Suites can be securely dated within the Weimar period; the remainder most likely originated during the early Cöthen years. The small manuscript books Bach dedicated to his eldest son Wilhelm Friedemann and his second wife Anna Magdalena, though begun in Cöthen, continued to be filled in after the move to Leipzig in 1723. And two of Bach’s most important collections, the Violin and Harpsichord Sonatas and the French Suites, were left finished when he moved away from Co¨then in 1723, with the result that he had to return to them in the early Leipzig years.

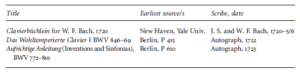

The keyboard collections were partly designed for teaching purposes. Tuition, which comprehended keyboard playing and composition alike, began in Bach’s own family circle and then spread outwards towards the private instruction of individual students. Thus, the Clavierbüchlein of 1720 and 1722, representing the domestic phase, included drafts of preludes destined for The Well-Tempered Clavier, of the Inventions and Sinfonias (then called ‘praeambula’ and ‘fantasias’), and of the French Suites. Later, fair copies were made of the first two of these collections, representing the public phase, and, like the Orgelbu¨chlein, revived from the Weimar years, they were furnished with title pages that clarified their didactic purpose. These title pages reveal the holistic nature of Bach’s musical philosophy: he is concerned not only with education but with pure delectation.

Thus, The Well-Tempered Clavier and the Aufrichtige Anleitung, as the fair copy of the Inventions and Sinfonias is entitled, are written not only for ‘those desirous of learning’ (‘denen Lehrbegierigen’) but for ‘those already skilled’ (‘als auch derer in diesem studio schon habil seyenden beson-derem ZeitVertreib’) and for ‘lovers of the clavier’ (‘denen Liebhabern des Clavires’). In addition, these title pages are concerned with issues of playing and composition alike. The Orgelbu¨chlein gives ‘instruction in developing a chorale in many different ways’ (‘Anleitung gegeben wird, auff allerhand Arth einen Choral durchzufu¨hren’), but also ‘in acquiring facility in the study of the pedal’ (‘anbey auch sich im Pedal studio zu habilitiren’). And the Aufrichtige Anleitung on the one hand shows how ‘to play clearly in two [and three] voices’ (‘mit 2 Stimmen reine spielen zu lernen, sondern auch . . . mit dreyen obligaten Partien richtig und wohl zu verfahren’) and how ‘to arrive at a singing style of playing’ (‘eine cantable Art im Spielen zu erlangen’), but, on the other hand, how ‘to have good ideas [and] develop them well’ (‘gute inven-tiones nicht alleine zu bekommen, sondern auch selbige wohl durchzufu¨hren’) and how ‘to acquire a strong foretaste of composition’ (‘einen starcken Vorschmack von der Composition zu u¨berkommen’).

In 1720 Bach suffered the heavy blow of the sudden death of his first wife Maria Barbara. It might have been partly for this reason that in November of that year he sought a new start in different surroundings, travelling to Hamburg as a candidate for the post of organist at the Jacobikirche. During the same visit, perhaps, Bach’s obituary (by C. P. E. Bach and J. F. Agricola) informs us that ließ sich daselbst, vor dem Magistrate, und vielen andern Vornehmen der Stadt, auf der scho¨nen Catharinenkirchen Orgel, mit allgemeiner Verwunderung mehr als 2 Stunden lang, h¨oren. Der alte Organist an dieser Kirche, Johann Adam Reinken, der damals bey nahe hundert Jahre alt war, ho¨rete ihm mit besondern Vergnu¨gen zu, und machte ihm, absonderlich u¨ber den Choral: An Wasserflu¨ssen Babylon, welchen unser Bach, auf Verlangen der Anwesenden, aus dem Stegreife, sehr weitla¨uftig, fast eine halbe Stunde lang, auf verschiedene Art, so wie es ehedem die braven unter den Hamburgischen Organisten in den Sonnabends Vespern gewohnt gewesen wahren, ausfu¨hrete, folgendes Compliment: Ich dachte, diese Kunst wa¨re gestorben, ich sehe aber, daß sie in Ihnen noch lebet.

(he was heard for more than two hours on the fine organ of St. Catherine’s before the magistrate and many other distinguished persons of the town, to their general astonishment. The aged organist of this church, Johann Adam Reinken, who at that time was nearly a hundred years old, listened to him with particular pleasure. Bach, at the request of those present, performed extempore the chorale An Wasserflu¨ssen Babylon at great length (for almost half an hour) and in different ways, just as the better organists of Hamburg in the past had been used to do at the Saturday vespers. Particularly on this Reinken made Bach the following compliment: ‘I thought this art was dead, but I see that in you, it still lives.’)

In the event Bach decided not to take the Hamburg post; and circumstances at Cöthen in any case soon changed for the better. Bach hired the young soprano Anna Magdalena Wilcke for the court in the summer of 1721, and he and she were married later in the same year (on 3 December). Only about a week after the wedding Prince Leopold also married. His bride, Friederica Henrietta of Bernburg, was unfortunately quite uninterested in music. Bach described the situation nearly ten years later in a letter to his former school friend Georg Erdmann:

6parti

die mutation, so mich als Capellmeister nach Co¨then zohe. Daselbst hatte einen gna¨digen und Music so wohl liebenden als kennenden Fu¨rsten; bey welchem auch vermeinete meine Lebenszeit zu beschließen. Es muste sich aber fu¨gen, daß erwehnter Serenißimus sich mit einer Berenbur-gischen Princeßin verma¨hlete, da es den das Ansehen gewinnen wolte, als ob die musicalische Inclination bey besagtem Fu¨rsten in etwas laulicht werden wolte, zumahln da die neu¨eF¨urstin schiene eine amusa zu seyn

([a] change in my fortunes . . . took me to Co¨then as Capellmeister. There I had a gracious prince, who both knew and loved music, and in his service I intended to spend the rest of my life. It must happen, however, that the said serenissimus should marry a princess of Berenburg, and that then the impression should arise that the musical interests of the said prince had become somewhat lukewarm, especially as the new princess seemed to be unmusical)6

For this and other reasons Bach sought the post of Cantor and Music Director at Leipzig, which had become vacant upon the death of Johann Kuhnau on 5 June 1722. Telemann and Graupner in turn were both chosen to fill the post by the Leipzig authorities, but neither could gain release from their current employment. Mean-while, Bach performed his audition cantatas Du wahrer Gott und Davids Sohn (BWV 23) and Jesus nahm zu sich die Zwo¨lfe (BWV 22) in the Thomaskirche on Quinquages-ima (Estomihi) Sunday, 7 February 1723. According to the local press, Bach’s music was ‘amply praised …by all knowledgeable persons’.7 After Graupner had declined the post, it was offered to Bach, who was elected on 22 April 1723. Bach and his family moved to Leipzig on 22 May, and his official duties began on the First Sunday after Trinity (30 May), when he performed his inaugural cantata before the Leipzig public, Die Elenden sollen essen,BWV 75. According to a Leipzig chronicle,8 its performance was regarded as a ‘great success’.

Leipzig, the second city of Saxony after the capital Dresden, had long been renowned for its trade and commerce, for its fairs, which took place three times a year, at New Year, Easter, and Michaelmas, and for its university, which had been founded in 1409. At this lively, thriving city Bach had a prominent post as ‘Cantor et Director Musices’—above all, he was responsible for music at the four main Leipzig churches. The pupils at the Thomasschule, where Bach taught, were divided into four cantorates, which provided the music at the four churches. At those with modest musical provision, the Neue Kirche and the Peterskirche, the two less able cantorates sang, and Bach was able to delegate their direction to others. The two leading cantorates, however, alternated on Sundays between the two principal churches, the Thomaskirche and the Nicolaikirche. The second cantorate had to sing relatively simple cantatas by composers other than Bach. The first cantorate, on the other hand, which had long been celebrated throughout Lutheran Germany—Schu¨tz’s Geistliche Chormusik had been dedicated to it—was given the task by Bach of

introduction 7

performing only his own exceptionally demanding compositions (this was not in his contract—compositions by others would have sufficed). As a result, during much of his first three or four years in Leipzig, while he was engaged in building up a new repertoire of church music, Bach composed a new cantata virtually every week, not to mention the task of having the performing parts copied and undertaking the neces-sary rehearsal. Only occasionally did the revival of an older composition from the Weimar years give him some respite. The reward for such diligence was the regular performance of his church works on Sundays and feast days at the Thomaskirche or the Nicolaikirche before a congregation of well over 2,000 people.9 The services concerned were without question the biggest musical events in Leipzig at the time.

Like his predecessors Schelle and Kuhnau, Bach was also responsible for the Old Service at the Paulinerkirche, the university church, which involved performing a cantata on the three High Feasts—Christmas, Easter, and Whit—as well as at the Reformation Festival (31 October). On these occasions Bach gave a repeat per-formance of the cantata that had already been performed that day in the Thomas-kirche or the Nicolaikirche.

The Kirchenstu¨ck, or cantata, as cultivated by Bach, was usually based on a biblical dictum or chorale text (most often from the Reformation period), whose theme, related to the Gospel or Epistle of the day, was then expounded in free verse. Generally, Bach would set the biblical or chorale text as an opening chorus of large dimensions, whereas the free verse would be set, in accordance with Neumeister’s reforms,10 as alternating recitative and arias. This ‘modern’ Italianate element, derived from opera and secular cantata, was thus wedded to the old German ecclesiastical element of dictum and chorale. The latter provided a foundation of sermon-like authority, whereas the more subjective, free-verse element allowed individual members of the congregation to relate the overall theme, or aspects thereof, to their own personal experience. Bach’s setting of the ecclesiastical texts would no doubt appeal to the church authorities; to what extent his pseudo-operatic treatment of the free verse did is a moot point,11 though it is interesting to note that on the occasion of his election, one of the councillors, Dr Steger, while voting for Bach, added that ‘he should make compositions that were not theatrical’.12 Furthermore, it was a condition of Bach’s appointment that in church he should ‘die Music dergestalt einrichten, daß . . . sie nicht opernhafftig herauskommen, sondern die Zuho¨rer vielmehr zur Andacht aufmuntere’ (‘so design the music that it should not create an operatic impression, but rather incite the listeners to devotion’).

8parti

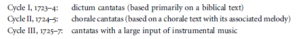

According to the obituary by C. P. E. Bach and Agricola,14 Bach wrote five cycles of cantatas for the whole church year, each of which would have numbered some fifty-nine compositions. Only three cycles survive in a virtually complete state, however, and all three originated during Bach’s first few years in Leipzig, when his enthusiasm for the project must have been at its height. They are:

Cycle IV might have originated in 1727–8 (see Part I Ch. 4), but very few cantatas from this period have been transmitted. Of Cycle V (1728–9) only eight cantatas survive.15 The texts are drawn from a complete set for the whole church year by Bach’s regular librettist Picander, who stated in his preface of 24 June 1728 that they were to be set to music by Bach. The fate of the remaining settings is not known. In general Bach’s lost cantatas, which might have numbered over 100, were probably for the most part inherited by W. F. Bach, who according to Forkel16 later had to sell them off. Occasionally, for various reasons, Bach resorted to the performance of cantatas by respected contemporaries. In the period 1724–5 he performed Telemann’s cantata Der Herr ist Ko¨nig (TVWV8:6); and in the early Trinity period of 1725 (Third to Sixth Sunday, 17 June to 8 July) a series of five Telemann cantatas might have been performed in the two main Leipzig churches, perhaps during Bach’s absence.17 In the following year Bach’s Meiningen cousin Johann Ludwig Bach provided him with a printed cycle of cantata texts, Sonntags- und Fest-Andachten (Meiningen, 1704) and with the scores of at least some of his own settings of these texts. Bach and assistants wrote out the parts and performed no fewer than eighteen of Johann Ludwig’s settings between 2 February (Feast of the Purification) and 15 September (Thirteenth Sunday after Trinity).18 Bach seems to have been so impressed with the librettos (and perhaps with Johann Ludwig’s settings) that he set seven of them himself during the latter half of this period, from Ascension Day, 30 May, onwards: BWV 43, 39, 88, 187, 45, 102, and 17.

On Good Friday of the same year, 19 April 1726, Bach revived an anonymous setting of the St Mark Passion (Hamburg, 1707) that he attributed, perhaps wrongly, to Reinhard Keiser. Bach had already performed this work in 1713, during his Weimar period. Its 1726 revival was the first of several Bach performances of Passions by other composers during the Leipzig years (see Part II Ch. 1 and Part III Ch. 1). Not long afterwards he might have performed Telemann’s setting of the Brockes Passion, for a copy from the 1720s was apparently in the library of the Thomasschule, Leipzig till the end of the Second World War.19 As for his own settings, the obituary informs us that he wrote five Passions, but only two survive: the St John and the St Matthew (of the St Mark Passion, first performed in 1731, only Picander’s libretto is extant). In Leipzig, according to J. C. Rost, sexton of the Thomaskirche, ‘on Good Friday of the year 1721, in the Vespers service, the Passion was performed for the first time in concerted style’,20 in a setting by Bach’s predecessor Johann Kuhnau. Bach continued this practice, and in musical terms the performance became the biggest event in the entire church calendar. The St John Passion was first performed on 7 April 1724, in the context of Cycle I, and then revived in a modified form—significantly including several elaborate chorale arrangements—on 30 March 1725, during the chorale-cantata cycle (Cycle II). The St Matthew Passion was first performed at Good Friday Vespers (11 April) 1727 and revived in 1729, though it did not acquire its definitive form till 1736. There is much in Bach’s two great oratorio-Passions—the seventeenth-century Lutheran genre to which he adhered—that could be described as dramatic or even theatrical, though we do not hear of objections raised by the clergy or members of the congregation. However, it is clear from the following account, published in Leipzig only a few years after the first performance of the St Matthew Passion, that strongly antagon-istic feelings were raised by Passion music in an operatic style:

When in a large town [such] Passion music was done for the first time . . . many people were astonished and did not know what to make of it. In the church pew of a noble family, many ministers and noble ladies were present, who sang the first Passion chorale out of their books with great devotion. But when this theatrical music began, all these people were thrown into the greatest bewilderment, looked at each other, and said, ‘What will come of this?’ And an old widow of the nobility said, ‘God save us, my children! It’s just as if one were at an opera comedy!’

The Leipzig opera had closed in 1720, before Bach’s arrival in the city, but other forms of secular music were frequently heard, in some cases performed by the Collegium musicum (music society) that had been founded by Telemann in 1701. Bach took over the directorship of this organization in 1729, but it is not unlikely that he was able to avail himself of its resources even before then. At any rate during the 1720shewas already composing and performing a good deal of secular music that anticipates the Collegium musicum period: drammi per musica (the equivalent of one-act operas), such as Der zufriedengestellte Aeolus (Aeolus Placated), BWV 205 (1725), Vereinigte Zwietracht,BWV207 (1726), and Die Feier des Genius (The Celebration of Genius), BWV 249b(1726); the Trauer-Ode (Mourning Ode), or Tombeau de S. M. la Reine de Pologne,BWV198 (1727); the solo cantata Von der Vergnu¨gsamkeit (On Contented-ness), BWV 204 (1727/8); and the wedding cantata Vergnu¨gte Pleißenstadt,BWV216 (1728). He also composed birthday cantatas for courts with which he had strong connections from of old: the pastoral cantata Entfliehet, verschwindet, entweichet, ihr Sorgen,BWV249a, for Weißenfels (1725) and Steigt freudig in die Luft,BWV 36a, for Cöthen (1726).

During these early Leipzig years, despite the huge demands made upon him by church music, Bach also engaged in concert activities outside the church. This is clear from an account by Ernst Ludwig Gerber, who informs us that in 1724 his father Heinrich Nicolaus ‘hatte . . . manche vortrefliche Kirchenmusik und manches Conzert unter Bachs Direktion mit angeho¨rt’ (‘had heard much excellent church music and many a concert under Bach’s direction’.)23 Music that he might have performed at this time includes the ouverture-suites in C and D, BWV 1066 and 1069, the Violin Concerto in E, BWV 1042, the Brandenburg Concertos, and perhaps the lost originals of some of the harpsichord concertos. At the same time Bach maintained contact with the court of Co¨then and the Saxon capital Dresden. He gave two extremely well-received organ recitals at the Sophienkirche, Dresden, in 1725. And in 1724, 1725, and 1728, alongside his second wife Anna Magdalena who was an able soprano, he gave guest performances in Co¨then in his capacity as Honorary Capellmeister. His first keyboard Partita (BWV 825) was dedicated to Prince Leopold’s newborn son in 1726; and finally he undertook the sad duty of composing and performing the prince’s funeral music in March 1729.

As we have seen, alongside his teaching duties at the Thomasschule, Bach under-took much private tuition in keyboard playing and composition—it is clear that he regarded the two as inseparable. For this purpose he made use of the two great collections that had been completed at Co¨then, The Well-Tempered Clavier I and the Aufrichtige Anleitung (the Inventions and Sinfonias). In addition, the French Suites were completed in the early Leipzig years and became popular among Bach’s pupils, and the English Suites now became available for teaching purposes. Prominent pupils, such as Bernhard Christian Kayser,24 Heinrich Nicolaus Gerber, and Johann Caspar Vogler, made their own copies of these works or selections from them. The very act of copying might have given them insight into the compositional techniques involved in their creation, while they no doubt gained practical knowledge of the music by learning to play it at the keyboard from their own copies. According to E. L. Gerber,

his father Heinrich Nicolaus studied Bach’s music under the composer in the order: Inventions, suites, Well-Tempered Clavier.

In 1725 Bach began a new Clavierbu¨chlein for his wife Anna Magdalena, entering two new keyboard suites at the start as a form of dedication. In revised versions these two compositions were later included in the set of six keyboard partitas that Bach published in separate instalments between 1726 and 1730, and then reissued in a collected edition as the First Part of the Clavieru¨bung (Leipzig, 1731). These partitas return to the large scale and considerable technical demands of the English Suites; and, like them, they were not primarily intended for teaching purposes. Instead, they were composed, according to the title page, ‘denen Liebhabern zur Gemu¨ths Ergoet-zung’ (‘for music lovers, to delight their spirit’);26 in other words, for the skilled amateur or connoisseur. By publishing these works one by one in the late 1720s, Bach made tentative steps towards one of the great projects of his later Leipzig years—the dissemination of his keyboard works in print in order to bring them to a far wider audience than he had hitherto been able to command.

The Well-Tempered Clavier I and other keyboard works

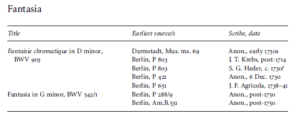

These two works represent the summit of Bach’s achievement in the free-fantasy style that he cultivated mainly in his earlier years. In the D minor composition, fugue might have been present from the outset; in the G minor, it was added at some later stage.1 But in both cases the fantasy element forms the main content of the work and defines its character. While neither work can be securely dated, an origin in the Co¨then (D minor) and Leipzig years (G minor) seems most likely.2

The Chromatic Fantasia and Fugue in D minor, BWV 903, one of Bach’s most extraordinary keyboard works, exists in three versions, though substantial changes are confined to the fantasia—the fugue seems to have remained largely unaltered. Nota-tional and stylistic features of the early version, BWV 903a, suggest an origin in the Co¨then period, around 1720.3 An intermediate version, transmitted by J. T. Krebs and S. G. Heder, is of uncertain date. The final, definitive version, copied by Agricola while he was a student of Bach’s, perhaps dates from the 1730s.

It has been observed that the work is not found in copies by Bach’s early Leipzig pupils, which suggests that the composer might have kept it to himself at first and not used it regularly for teaching purposes till the 1730s; or else he might have returned to it then after a long interval. If so, a possible use of the work might have been as a virtuoso showpiece in Collegium musicum concerts.

In spite of its singular qualities, highlighted in Forkel’s oft-quoted remark that ‘this fantasia is unique and never had its like’, the Chromatic Fantasia may be viewed as the culmination of Bach’s writing in pseudo-improvisatory style for the harpsichord (according to the title pages of some of the chief sources,6 it is specifically written ‘pour le clavecin’).

Not only is it a brilliant, virtuoso showpiece, with which Bach must have dazzled his first audiences, but it is also a chromatic and enharmonic tour de force. It exhibits a fully chromatic command of the keyboard and of the resources of tonality, of the kind that Bach is said to have displayed in his improvised fantasies. ‘When he played from his fancy,’ Forkel informs us, ‘all the 24 keys were in his power; he did with them what he pleased.’

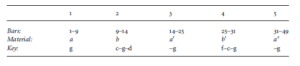

The chromatic element in the great fantasia is progressively intensified in the course of its three paragraphs and coda. The first paragraph is an extended passaggio that half-closes in the tonic at b. 20. The second (bb. 21–49) introduces arpeggiando chords in alternation with further passaggi. The third (bb. 49–74) modulates to the furthest reaches of the tonal system and back within the context of an instrumental recitative (so designated)—a style of writing that Bach had attempted before (in BWV 912a and 922) and would also have encountered in the slow movement of Vivaldi’s ‘Grosso Mogul’ Concerto (RV 208), which he transcribed for organ (BWV 594). The modulations of the fantasia’s recitative produce the effect of astounding, spon-taneous strokes of genius, despite the careful tonal planning that clearly underlies the passage. We encounter here the contradiction that lies at the heart of the pseudo-improvisatory style from Frescobaldi to Bach—that great art has to be deployed in order to conjure up the impression of spontaneity. In the coda (b. 75), the treble descends chromatically through an octave, while the rich, full chords of the accompaniment simultaneously undergo their own fully chromatic descent—total chromaticism prevails. Yet the entire coda is underpinned by a tonic pedal. We thus meet the further contradiction here that, at the point in the fantasia where Bach’s chromaticism is most explicit, it is also most firmly grounded in the home key.

By its very nature, the great fantasia is quite athematic. In comparable earlier cases, however (BWV 912a, 922, etc.), Bach had often introduced music structured around a 14 definite theme as a counterbalance to the improvisatory freedom that otherwise prevailed. This was no doubt the raison d’eˆtre for the fugue that follows the fantasia, whether or not it was part of the original conception—the different key signatures of fantasia and fugue (the one without flat, the other with) might be signs of separate origin. Certain aspects of the fugue seem to represent the opposite pole from free fantasy: the clearly articulated subject, with its sequential headmotive (a recurring feature of Bach’s Weimar fugues) and its inversion halfway; the use of a well-defined, regular countersubject; the substantial element of reprise, an import from concerto form; and the clear division of the modulatory phase into sharp-side and flat-side zones (as in the fugues from BWV 542 and 894, etc.).

On the other hand, certain other features of the fugue make it seem a perfectly natural and consistent outcome of the fantasia that precedes it. The most obvious of these is, of course, the chromatic nature of the sequential headmotive. No less significant, however, is the tonally unstable character of the subject, its refusal to settle into a clearly defined key till after the halfway point. To this we must add the bold, unprepared 7th that bursts upon the scene at the answering entry of the subject (b. 9) and the inexactness of that answer due to the dotted rhythm that opens it, which is later taken up in an episodic sequence (bb. 72–5). Finally, during an E minor subject entry (b. 90) the three-part fugal texture suddenly explodes into an eight-part dominant-9th chord (b. 94)—among the sharpest dissonances known to Bach—which recurs with climactic effect during the last stages of the fugue (bb. 135–9 and 158).

If the Chromatic Fantasia in D minor represents the ne plus ultra of Bach’s free-fantasy works for harpsichord, the Fantasia in G minor (BWV 542 no. 1) occupies a similar position among his organ works. The two works differ, however, in the role played by fugue. Whereas that of the D minor composition was either present from the outset or else added at a very early stage, there is no incontrovertible evidence that the pairing of fantasia and fugue in the G minor work goes back to Bach at all.8 The G minor Fantasia is very clearly articulated into five paragraphs as follows:

Unlike the Chromatic Fantasia, this composition incorporates a fully structured element within itself, namely the triple-counterpoint episodes b and b1, which alternate with writing in improvisatory style. The overall form is rondeau-like, not only in its contrasting episodes and (admittedly, very free) returns, a1 and a2, but also in its key structure, returning repeatedly to the tonic. In addition, whereas the Chromatic Fantasia is entirely through-composed, this work incorporates significant elements of reprise, even within its free passages. Thus paragraph 5 recapitulates much of para-graph 3 in reverse order and in different keys (bb. 36–8 = 21–3; 44–6 = 15–17). To a far greater extent than in the Chromatic Fantasia, then, improvisatory freedom is here checked and modified by structural restraint, which would be consistent with a later dating for this composition.

The links that can be established with the harpsichord work are, however, no less obvious than the differences. Among them are the totally athematic character of the improvisatory-style passages, and the recurring ‘sigh’ figure, whether it takes the form of single appoggiaturas (D minor Fantasia) or multiple suspensions (G minor). Again, while only the harpsichord work is actually termed ‘chromatic’, the term might have been quite aptly applied to the organ work too: some of its most intense and mysterious passages of all are built on the basis of a chromatic ascent (pedals: bb. 20–3, 36–8; manuals: bb. 31–4). Among the most obvious resemblances between the two pieces are the startlingly abrupt, seemingly spontaneous modulations to unrelated keys, brought about by enharmonic change or by the changing tonal function of pivot notes. In stylistic terms the organ fantasia shares with its harpsi-chord counterpart two different species of improvisatory-style writing, namely pas-saggio (para. 1) and instrumental recitative (paras. 3 and 5). But the incorporation of these rhapsodic elements within the highly structured overall framework of the G minor Fantasia suggests, as has already been noted, a later date of origin than that of the D minor—perhaps Leipzig (1720s?) rather than Cöthen. Improvisatory freedom is now no longer possible except in conjunction with tight control.

Prelude, fugue, and invention

A new approach to keyboard music is clearly evident in Bach’s Co¨then and early Leipzig years. In their initial or early stages new compositions were often entered into small manuscript keyboard books called ‘Clavierbüchlein’ (equivalent, in name at least, to ‘Orgelbüchlein’), dedicated to Bach’s eldest son Wilhelm Friedemann or to his second wife Anna Magdalena.

Family members were thus the first to benefit from Bach’s newest ideas. As his compositions developed, they would be copied by pupils from Bach’s immediate circle, such as Heinrich Nicolaus Gerber, who could then profit from them in their keyboard and composition studies. Finally, a definitive autograph fair copy would be produced, from which (at least indirectly) large the well-tempered clavier i etc. numbers of copies could be made, allowing dissemination of the work over a more extensive area. In its final form the work would consist of a standard set of six compositions, as in the suites or violin solos, or a multiple of six, as in the twenty-four Preludes and Fugues or the thirty Inventions and Sinfonias. Collecting together compositions in sets of six or more was, of course, customary at the time, but for Bach around 1720 it had a special significance: a new desire—no doubt linked to the arrival of full creative maturity—to be fully comprehensive and exhaustive in his approach to any keyboard form, whether it be dance suite, prelude and fugue, or the newly devised ‘invention’.

The early exposure of family and pupils to these compos-itions is closely bound up with their very conception: they are designed not simply for pure delectation but as composition models and keyboard studies. These aims cannot be dissociated from each other: they are entirely integrated within the fabric of each composition.

Among the first items in the Clavierbu¨chlein for W. F. Bach are five praeludia or praeambula, BWV 924, 926–8, and 930, all but one of which were entered by J. S. Bach in 1720,9 the year in which the book was dedicated to his son (the exception is BWV 927, which was entered by W. F. Bach in 1722/6). The first two preludes are numbered 1 and 2, and are in the keys of C major and D minor, which suggests that Bach might originally have planned a set of preludes in ascending key order. The five existing preludes, clearly designed specifically for the musical education of the young Wilhelm Friedemann, proceed from the simplest type, the arpeggiation of a chord sequence; hence the first two pieces, BWV 924 and 926, may be described as arpeggiated preludes. The other three preludes are also built on arpeggiated chords, but this material is now used thematically in sequence (BWV 927), motivically in imitation (BWV 930), or as the thematic material of a miniature ritornello design within an overall ABA1 structure (BWV 928).

The preludes thus offer an instructive course of progressively increasing difficulty. That it was partly intended as a composition course is suggested by the three praeludia in the key order C, D, e (BWV 924a, 925, and 932) that W. F. Bach entered in the book in 1725/6 in imitation of his father. J. S. Bach’s preludes were clearly intended for keyboard instruction too, however, hence the ornamentation, which refers back to the ‘Explication’, a table of ornaments that Bach wrote out in imitation of D’Anglebert and Dieupart; hence, too, the four-bar cadenza in the D minor Prelude (BWV 926,bb.39–42) and the fingering that Bach supplied throughout the G minor (BWV 930).

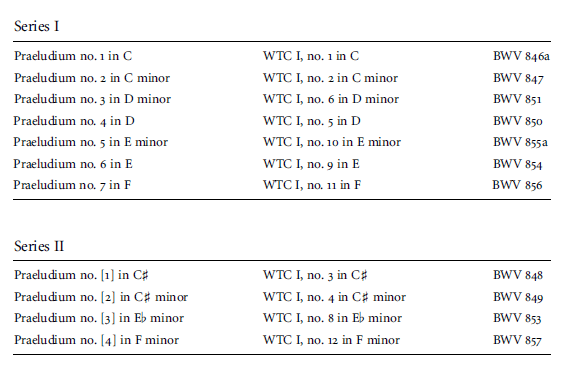

Some months later, probably in 1721, W. F. Bach, with the help of his father, started copying into the Clavierbüchlein a series of preludes that would eventually be incorporated in The Well-Tempered Clavier I (henceforth WTC I). A second series followed in 1722–3. The two series are as follows:

As shown, the keys of the first series are those of the diatonic tetrachord C–F, while those of the second series fill the chromatic gaps (except for E♭, which is missing). The versions of the first series are similar to those of the Forkel manuscripts, the chief sources of the early version of the WTC I, though slightly revised. The versions of the second series are similar to those of Bernhard Christian Kayser’s copy of the WTC I (Berlin, Mus. ms. Bach P 401), made in 1722–3, which represents the stage immediately before the autograph fair copy.

The first series, like the five preludes of 1720, represent a progressive course of instruction in composition and keyboard technique. Again, Bach begins with the arpeggiated prelude, first in simple form (no. 1 in C), then with figured arpeggios (the so-called arpègement figuré; no.2 in c); triplet arpeggios against a quaver bass (no. 3 in d); broken chords decorated by an ostinato motive in two-part texture with running treble and spaced-quaver bass (no. 4 in D), then the same with interchanged parts (no. 5 in e); thematic use of an arpeggio figure as the basis of a cantabile piece in three-part texture (no. 6 in E); and finally, motivic use of an arpeggio figure in exchanges between treble and bass (no. 7 in F). The first series of preludes, then, are not only numbered 1–7 and arranged in a logical key order, but they are also technically graded, both as keyboard and composition studies, and closely interrelated in style, theme, and motive.

All this suggests that they might have been composed as a group. This is not to say that they were necessarily composed with W. F. Bach’s musical education in mind, as the earlier set of preludes (BWV 924, 926–8, and 930) obviously were. It is more likely that, around 1720–1, Bach was working on the beginnings of the WTC I and simultaneously assisting his young son, and that there was a substantial overlap between the two tasks. The second series of WTC preludes were entered in the Clavierbu¨chlein at a later stage (1722–3), when the WTC I was nearing completion. Here the child would learn to play in double counterpoint, with perfect equality of the two hands (no. 1 in C♯), and in cantabile style within a freistimmig (free-voiced) texture (nos. 2–4). It is notable that three of the four preludes have tonics on the black keys, in accordance with Werckmeister’s prediction that eventually musicians would be able to play equally ‘aus dem coder cis’, which was certainly part of Bach’s achievement, if not part of his intention.

In the end the Clavierbüchlein contained all twelve preludes from the first half of the WTC I, copied out by the son with his father’s assistance, with the exception of no. 7 in E♭, which was no doubt felt to be excessively long and hard for the young Wilhelm Friedemann.

Alongside other manuscripts the Clavierbüchlein offers certain hints as to how the WTC I might have evolved in its early stages. The Clavierbüchlein, B. C. Kayser’s copy (P 401), and J. G. Walther’s copy (P 1074), taken together, suggest that Bach might have originally composed a series of preludes (and fugues?) in the diatonic key order Cc, dD, eE, fF, gG, aA, subsequently filling in the gaps to create a fully chromatic series. This theory is supported by the later date of the second series of WTC preludes in the Clavierbüchlein and by the observation that there would have been room there for between seven and ten additional preludes. The early versions of Preludes 1–15 in the Forkel manuscripts, seven of which recur in the Clavierbüchlein, are mostly a good deal shorter than the definitive versions, whereas the earlier and later versions of the fugues differ only in matters of detail.

It is possible, then, that the WTC I might have been compiled from a collection of preludes in the keys C–G (or C–a) and that, in the first place, the fugues might have formed a separate collection. Gaps might have been filled not only by composing new pieces ad hoc but by adapting existing pieces. There is some evidence in the sources that the more remote keys might have been catered for by transposition. Praeludium et Fuga 8 in e♭/d♯, for example, might have been transposed from e/d, which would imply separate origin for prelude and fugue; no. 18 might have been transposed from g to g♯, and no. 24 from c or g to b. There are signs in the sources that some preludes and fugues originally had the old modal key signatures (one flat or sharp fewer than today’s signatures); for example, in Kayser’s copy Fuga 2 in C minor has a key signature of two flats. In addition, among the early sources the title ‘Pre´lude’ is found, as well as ‘Praeludium’, and ‘Fughetta’ in place of ‘Fuga’.

On the evidence of Kayser’s copy the WTC I was probably compiled by collecting together separate bifolios, each of which would have contained a single prelude-and-fugue pair under its own title. These bifolios would have been combined to form a composite manuscript (now lost), within which folios could be inserted or replaced at will, serving as a vehicle for the compilation process in much the same way as the British Library autograph did for the WTC II about twenty years later. The existing autograph fair copy of Part I (P 415) was probably begun in late 1722,when the compilation process and the main revision of the text were complete. The object of this manuscript was clearly to bring the work into its definitive form. A further revision of the text was undertaken. The key order became fully chromatic, with major preceding minor throughout. Modern key signatures were invariably used. Individual titles throughout took the form ‘Praeludium 1’or‘Fuga 1’ and so on. The word ‘fine’ now occurs only at the end of the whole collection, not after each prelude-and-fugue pair, as it did originally. Finally, after ‘fine’ Bach writes ‘SDG’, soli Deo gloria, his customary sign of completion.

The elaborate ornamental title page of the autograph fair copy reads:

Das Wohltemperirte Clavier oder Praeludia und Fugen durch alle Tone und Semitonia, so wohl tertiam majorem oder Ut Re Mi anlangend, als auch tertiam minorem oder Re Mi Fa betreffend. Zum Nutzen und Gebrauch der Lehr-begierigen Musicalischen Jugend, als auch derer in diesem studio schon habil seyenden besonderem Zeit Vertreib auffgesetzet und verfertiget von Johann Sebastian Bach p. t. Hoch Fu¨rstlich Anhalt-Co¨thenischen Capellmeistern und Directore derer Cammer Musiquen. Anno 1722.

(The Well-Tempered Clavier, or Preludes and Fugues through all the tones and semitones, both as regards the tertia major or Ut Re Mi and as concerns the tertia minor or Re Mi Fa. For the use and profit of the musical youth desirous of learning, as well as for the pastime of those already skilled in this study, drawn up and written by Johann Sebastian Bach, p. t. Capellmeister to His Serene Highness the Prince of Anhalt-Cöthen and director of his chamber music. In the year 1722.)

Bach’s circumlocutory terminology for the major and minor modes is borrowed from Kuhnau. ‘Clavier’ in this context most likely means simply ‘keyboard’, the commonest meaning of the word at the time. In other words, Bach is deliberately non-prescriptive as to the type of instrument that should be used. This is in keeping with the restriction of the work to C–c3, the standard keyboard compass at the time, which made it as widely playable as possible on the instruments then in use.

The epithet ‘wohltemperirte’ (well-tempered) was clearly borrowed from the leading contemporary authority Andreas Werckmeister, who frequently made use of it in his theoretical works. His treatise of 1691, for example, is entitled Musicalische Temperatur, oder deutlich und warer mathematischer Unterricht, wie man . . . ein Clavier . . . wohl temperirt stimmen ko¨nne (Musical Temperament, or clear and true mathematical instruction how to tune a keyboard well-tempered). Here, as elsewhere in Werckmeister’s writings, ‘wohl temperirt’ evidently means ‘appropriately tuned’. But in his later writings he increasingly advocated equal temperament on account of its unlimited possibilities of modulation, transposition, and enharmonic change. It is not necessary, however, to adopt entirely equal temperament in order to play in all keys. And many theorists of Bach’s day, such as Neidhardt, Mattheson, Sorge, Marpurg, and Kirnberger, advocated a slight deviation from absolute equality in order that the distinctive colourings of different keys could be maintained. It may well be that something approaching equal temperament, but subtly nuanced in this way, was what Bach had in mind. Or else he might have meant by ‘wohltemperirte’: use whatever temperament you find appropriate for playing music in all keys.

The didactic purpose of the work is clear from the words ‘for the use and profit of the musical youth desirous of learning’. And indeed for Bach’s pupils it became the prime vehicle for advanced study in both keyboard playing and composition. The work was also intended for pure delectation, however, as is clear from the words ‘as well as for the pastime of those already skilled in this study’.

By including a prelude and fugue in every one of the twenty-four major and minor keys, Bach gave a practical demonstration of the full range of the tonal system. There were at least partial precedents, of course, of which only the most prominent can be mentioned here. Since the traditional function of the prelude was to establish the mode of the work that followed, each prelude in sixteenth- and early seventeenth-century published collections tended to be in a different mode. By the late seventeenth century this procedure was applied to keys rather than modes. For example, the Tabulatura 12 Praeambulorum . . . durch alle Claves und Tonos auff Clavichordien und Spinetten zu gebrauchen (Tablature of 12 Praeambula through all the keys and tones, to be used on clavichords and spinets) of 1682 by the Dresden court organist Johann

Heinrich Kittel contains one prelude in each of the twelve most common major and minor keys, those with up to three sharps or flats. An even greater range of keys was occasionally in use at that time—for example, in the seventeen anonymous suites of 1683, formerly attributed to Pachelbel, whose keys include a major and/or a minor on every degree of the chromatic scale. By the turn of the century it was possible to list all twenty-four keys, with modern key signatures and in fully chromatic order, as did the organist T. B. Janovka in his influential treatise Clavis ad thesaurum magnae artis musicae (Prague, 1701). Since this work was known to Johann Bernhard Bach and Johann Gottfried Walther, it is quite possible that Bach was acquainted with it.

The nearest precedent to the WTC I was published in the following year, 1702: Ariadne musica, a collection of twenty preludes and fugues in nineteen different keys by the South German composer Johann Caspar Ferdinand Fischer. Here only five remote keys are missing from the complete cycle of twenty-four: g♯,b♭,e♭,F♯, and C♯. Certain rather conservative, seventeenth-century features of the collection, how-ever, distance it from the WTC I. Fischer’s preludes and fugues are tiny miniatures, reflecting the South German verset tradition; and the frequent ‘modal’ key signa-tures show that he was often thinking in terms of transposed modes rather than modern keys.

Despite these antiquated features, there is no doubt that Bach was acquainted with the work and that it exerted a powerful influence upon the conception and composition of the WTC I. Although Ariadne first appeared in 1702,as already noted, it is known today only from a later edition (Augsburg, 1715). Bach, too, might have known only this 1715 edition. That would account for the absence of any trace of the influence of Ariadne on Bach’s keyboard music prior to 1715. In addition, it would square with the likely date of the WTC’s conception—some time within the period 1715–20. The overall structure of the two works is remarkably similar: a ‘Praeludium et Fuga’ in all the major and minor keys (or nearly all, in Fischer’s case), chromatically ordered from C to b. Fischer places minor before major through-out, a relic of modal theory that recurs in the early stages of Bach’s work on the WTC I. Later, we shall have occasion to notice how often even the substance of Fischer’s preludes and fugues resonates in the later work.

J.S. Bach, The Well-Tempered Clavier, Book 1 / Sviatoslav Richter ( 1969 )

Download and Read the full book: The Creative Development of J.S. Bach (Vol. 2)

Browse in the Library:

Or browse in the categories menus & download the Library Catalog PDF: