- Robert Fripp, the amazing guitarist (3): KING CRIMSON (first part)

- King Crimson I: the beginning

- Giles, Giles and Fripp

- The Genesis of King Crimson I

- In the Court of the Crimson King

- 21ST CENTURY SCHIZOID MAN

- King Crimson I Live

- I TALK TO THE WIND

- EPITAPH including MARCH FOR NO REASON and TOMORROW AND TOMORROW

- MOONCHILD including THE DREAM and THE ILLUSION

- THE COURT OF THE CRIMSON KING including THE RETURN OF THE FIRE WITCH and THE DANCE OF THE PUPPETS

- King Crimson II

- In the Wake of Poseidon and Lizard

- Islands and Earthbound

- ISLANDS

- EARTHBOUND

- Listen to: King Crimson – 21st Century Schizoid Man

- Lyrics:

- Download the best Rock sheet music from our Library.

Robert Fripp, the amazing guitarist (3): KING CRIMSON

Robert Fripp, the amazing guitarist (3): KING CRIMSON (first part)

King Crimson I: the beginning

References to the printed booklet included in The Young Persons’ Guide to King Crimson are herein indicated by the abbreviation YPG followed by column numbers. The booklet itself, however, contains neither page nor column numbers. Therefore, if you wish to find the exact location of a YPG quotation listed in these Notes, you must number the columns in YPG yourself. Begin with “1” at the first column (1968-June 1).

Fripp was born in Wimbourne, a village ten miles outside Bournemouth. We know little about the young Bob Fripp’s life; occasional tidbits filter down through the press, such as that his favorite subjects in school were English and English literature. (Dery 1985, 51) Only very rarely has Fripp exposed anything about his childhood in interviews.

One such instance was in 1980, when he talked about the double binds he found himself in as a boy, and which he later managed to work through in transactional analysis: “My parents made me crazy. My father didn’t want children and I’d say ‘Mum, Father’s irritable’ and she’d say ‘no he’s not!’ and there’s my father boxing me round the ears. So how can you process that information and experience?” (Recorder Three, 1980, n.p.)

From the age of eleven, when his parents had bought him his first guitar on December 24, 1957, Fripp had known that music was to be his life. From the age of fourteen, he had various miscellaneous performing experiences, playing guitar in hotels and restaurants and backing up singers. He soaked up influences: first American rockers like Scotty Moore, Elvis Presley, Chuck Berry; a bit later, Django Reinhardt and modern jazz.

A turning point was reached at the age of seventeen; as Fripp describes it, “I went to stay with my sister on holiday in Jersey. And I took my guitar. I had lots of opportunities to practice there, which I found quite wonderful. It was there that I established a deeper relationship with the instrument. And upon returning home to England, I announced to my mother, ‘I am going to become a professional guitar player.’ My mother didn’t try to dissuade me. She simply burst into tears. I took her reaction to heart and my decision was delayed until I was twenty.” (Milkowski 1984, 29-30)

Fripp’s steadiest gig, beginning at age eighteen, was a three-year stint at the Majestic Hotel, in the band hired to entertain the Hebrew Fraternity of Bournemouth. If it is difficult to imagine Robert Fripp meekly chiming in on twists, foxtrots, tangos, waltzes, the Jewish National Anthem, Hava Nagilah, and “Happy Birthday Sweet Sixteen,” consider that he got the job when the young Andy Summers (later guitarist for the Police) vacated the post to go to London. (Garbarini 1984, 39)

In the meantime, Fripp was being groomed by his father to take over the latter’s small real estate firm; having worked for his father for three years, Fripp felt that to educate himself further in the business he should get away from the office. He studied for a year and a half at Bournemouth College, taking A-levels in economics, economic history, and political history; the idea was to go to London and pursue a degree in estate management.

But at the age of twenty Fripp decided, in his own words, that he “could no longer be a dutiful son” (Drozdowski 1989, 31) and resolved to have a go at the music business. He felt that “becoming a professional musician would enable me to do all the things in my life that I wanted,” (Rosen 1974, 18) that it would provide him with the best possible education.

He proceeded to form what he has referred to as an “incredibly bad semi-pro band” called Cremation. (Rosen 1983, 19) Cremation did land a few gigs, but Fripp ended up canceling most of them – the group was so awful he was afraid of jeopardizing what local musical reputation he had been able to earn.

Nineteen sixty-seven was perhaps the high-water mark of the rock explosion of the 1960s; anything could happen in music, and there was a sense that, for once, the groups that were the best in a creative sense could also be – indeed, often were – the most popular.

In provincial Bournemouth, Fripp was catching whiffs of this exhilarating spirit: “I remember driving over to the hotel one night and on the radio I heard Sgt. Pepper’s for the first time. I tuned in after they’d introduced the album. I didn’t know who it was at first, and it terrified me – ‘A Day in the Life,’ the huge build-up at the end. At about the same time I was listening to Hendrix, Clapton with John Mayall’s Bluesbreakers, the Bartok string quartets, Stravinsky’s The Rite of Spring, Dvorak’s New World Symphony … they all spoke to me in the same way. It was all music. Perhaps different dialects, but it was all the same language. At that point, it was a call which I could not resist … From that point to this very day [1984], my interest is in how to take the energy and spirit of rock music and extend it to the music drawing on my background as part of the European tonal harmonic tradition. In other words, what would Hendrix sound like playing Bartok?” (Milkowski 1984, 30)

Giles, Giles and Fripp

In Bournemouth in the spring of 1967, Fripp auditioned for a position in a band being formed by drummer Michael Giles and bassist Peter Giles. The trio rehearsed and moved to London that fall to work a gig accompanying a singer in an Italian restaurant. The gig fell through after a week, but Giles, Giles and Fripp persevered through 1968, managing to appear on a couple of television shows and to record and release two singles (“One in a Million” / “Newlyweds”) and “Thursday Morning” / “Elephant Song”) and an album, The Cheerful Insanity of Giles, Giles and Fripp.

For those whose exposure to Fripp’s music begins with King Crimson, the music of Cheerful Insanity, now something of a collector’s item, might come as a shock. For one thing, it’s not in the least heavy – it’s a collection of frothy little absurdist ditties. The tunes on Side One are interspersed with Fripp’s spoken recital of a sort of tongue-in-cheek morality poem he called “The Saga of Rodney Toady,” a fat, ugly lad who is the butt of cruel jokes. We are all familiar with McCartney music-hall nonsense verse along the lines of “Maxwell’s Silver Hammer”; a lot of Cheerful Insanity is kind of like that – light, whimsical, gently satirical – except that the orchestration is even sillier.

Fripp’s playing is accomplished enough, but to hear the Crimson king of Marshall-stacks distortion mildly riffing along in best cocktail-lounge-jazz fashion is a bit of a revelation. Even here, Fripp couldn’t resist showing off his chops a little, however; his “Suite No. 1” features him ripping along playing a continuous melody in sixteenth notes at a quarter note of 148 beats per minute. Only two other songs – “The Cruckster,” with its jagged, dissonant guitar effects and primitive reverb, and “Erudite Eyes,” which sounds at least partially improvised – give any indication of musical paths Fripp was later to follow.

Cheerful Insanity is a very English record. The Hungarian Bartok hadn’t quite yet made the acquaintance of the American Hendrix; the album sounds like a collaboration between Monty Python and the Moody Blues in one of their less pompous moods. After Giles, Giles and Fripp, Fripp’s sense of humor may have remained intact in his day-to-day life, but it went decidedly below the surface in his music.

The Genesis of King Crimson I

According to Fripp, on November 15, 1968, King Crimson was “formed in outline between Fripp and Michael Giles in the kitchen following a fruitless session of Giles, Giles and Fripp at Decca.” (YPG, 1) Fripp summed up the demise of Giles, Giles and Fripp as follows: “The dissolution of Giles, Giles and Fripp followed some 15 months of failure and struggle.

We were unable to find even one gig. World sales of the album within the first year were under 600. My first royalty statement showed sales in Canada of 40 and Sweden of 1. Peter Giles left to become a computer operator and finally a solicitor’s clerk although played on sessions for a while, notably ‘Poseidon’ and McDonald and Giles.” (YPG, 1) (McDonald and Giles, released in 1971, was another relatively lightweight affair, though not so bubbly as The Cheerful Insanity of Giles, Giles and Fripp; it was ample proof of the divergent directions Fripp and his early collaborators were taking after King Crimson I broke up.)

Drummer Michael Giles, born near Bournemouth in 1942, was the oldest of the members of the original King Crimson lineup. He began playing drums at the age of twelve, and played in jazz and skiffle groups in the 1950s, then in rock bands in the 1960s. When Fripp and Giles decided to form a new group, Fripp’s first move was to enlist the services of another Bournemouth native, Greg Lake, a singing guitarist with the group Shame who subsequently switched to bass during his stint with the Gods.

Giles and Fripp then sought out a songwriting team, which turned out to be lyricist Peter Sinfield along with composer and multi-instrumentalist Ian McDonald, who could play various reeds and woodwinds as well as vibraphone, guitar, and keyboards. Some of McDonald’s early influences were Louis Belson, Les Paul, and Earl Bostic, plus classical composers like Stravinsky and Richard Strauss; during a five-year hitch as an Army bandsman, he had studied traditional orchestration and music theory, and by the time he joined King Crimson he had played in dance bands, rock groups, and classical orchestras.

Both McDonald and Lake were more than competent guitarists; upon joining King Crimson Lake played only bass, and McDonald performed duties on reeds, woodwinds, vibes, and keyboards, leaving Fripp as the sole guitarist. This appears to have been a gesture of deference if not quite a sign of intimidation: as one of the early King Crimson musicians reportedly put it, “When Bob Fripp is in your band, you just don’t play guitar.” Fripp, in fact, would not actively collaborate with other guitarists until he enlisted the services of Adrian Belew in the 1980s version of King Crimson.

Sinfield had been working as a computer operator when he left the job to found the group Infinity; McDonald was Infinity’s guitarist, and after the band’s demise (Sinfield later called it “the worst group in the world”), McDonald and Sinfield stayed together in order to keep writing. Sinfield became an “invisible” member of King Crimson, providing words for the songs, acting as road manager and lighting director, and evidently serving as a sort of conduit between the hip London culture and the provincial members of King Crimson, telling them where they should go to buy the right kind of clothes, and so on. Sinfield’s role was also that of musical consultant, an in-studio audience off of whom Fripp could bounce ideas. (Williams 1971, 24)

Although he never performed with Crimson on stage, he was very much part of the evolving group dynamics of the band until his departure in late 1971. It is to Sinfield that the world owes the Mephistophelean moniker “King Crimson”: Fripp relates that “Pete Sinfield was trying to invent a synonym for Beelzebub.” (Schruers 1979, 16) Beelzebub, prince of demons, the Devil – for Milton in Paradise Lost Beelzebub was the fallen angel who ranked just below Satan.

Fripp has told some amusing anecdotes about band and bar life in swinging London in 1969 – for instance, how Greg Lake, with whom he shared a small apartment for a time, regarded him as “inept” in picking up girls, and “took it on himself to give me some help in strategy and maneuvers.” (Fripp 1982A, 35-6)

On January 13 1969, the first official King Crimson rehearsal took place in the basement of the Fulham Palace Cafe in London – the space that was to become their rehearsal room for the next two and a half years. It would have been fascinating to be a fly on the wall of the basement during the first few months of 1969 – to observe and try to understand how four musicians (and one lyricist) come together and fuse into a single organism.

In point of fact, it became a custom for King Crimson to invite an audience of friends to their basement rehearsals, and reports of a powerful new sound began to leak out. Fripp has written of this period: “Following several years of failure we regarded King Crimson as a last attempt at playing something we believed in. Creative frustration was a main reason for the group’s desperate energy. We set ourselves impossibly high standards but worked to realize them and with a history of unemployment, palais and army bands, everyone was staggered by the favorable reactions from visitors … With the fervor of those months I could write for a publicity handout: ‘The fundamental aim of King Crimson is to organize anarchy, to utilize the latent power of chaos and to allow the varying influences to interact and find their own equilibrium. The music therefore naturally evolves rather than develops along predetermined lines. The widely differing repertoire has a common theme in that it represents the changing moods of the same five people.’“ (YPG, 2)

Most of the pieces the group rehearsed were newly composed, but one or two came out of the Giles, Giles and Fripp repertoire, such as “I Talk to the Wind.” The group also played through versions of the Beatles’ “Lucy in the Sky with Diamonds” and Joni Mitchell’s “Michael from Mountains,” which Judy Collins had recorded in an arrangement by Joshua Rifkin on her Wildflowers album of 1967. The “feminine,” soft-focus yet tightly orchestrated ballad was a feature of most early King Crimson albums; one reporter relates how the group would listen to Judy Collins records to unwind after difficult, tense rehearsals.

At this stage in the evolution of the band, compositional duties tended to be spread over the whole ensemble; for many pieces, it wasn’t a matter of one songwriter coming in with a chart and everyone following his directions. Rather, the group played, fought, improvised, ran through numbers, trying to catch the good ideas as they flew by. Curious to find out more about this process, I asked Fripp about it in 1986.

What was the genesis of “21st Century Schizoid Man,” for instance? Fripp’s memory was crystal-clear, and he answered very methodically, “Well, the first few notes – Daaa-da-da-daa-daa-daaaa – were by Greg Lake, the rest of the introduction was Ian McDonald’s idea, I came up with the riff at the beginning of the instrumental section, and Michael Giles suggested we all play in unison in the very fast section toward the end of the instrumental.” I thought it would be fascinating to know how a number of different King Crimson songs were stitched together like this, but Fripp declined further explication; he didn’t think it very interesting or particularly valuable. Perhaps he deemed King Crimson’s group identity – its “way of doing things” – more important and relevant than the specific contributions of individual members.

On other occasions, with other writers, Fripp has been a bit more forthcoming with regard to King Crimson’s compositional process. He admired and wanted King Crimson to emulate the Beatles’ proclivity for packing many strands of meaning into a song, so that a record could stand up to repeated listenings: “The Beatles achieve probably better than anyone the ability to make you tap your foot first time round, dig the words sixth time round, and get into the guitar slowly panning the twentieth time.” Fripp wished Crimson could “achieve entertainment on as many levels as that.”

Most of King Crimson’s recorded music appears to be tightly structured, but in fact the forms have a certain amount of flexibility built in. While the architecturally important lead lines that connect the music together are fixed, other elements are variable in live performance, such as the drum patterns, the choice of octave for the melodic parts, and even the harmonies. A great deal depended on the inspiration of the moment: “If you’re feeling particularly happy you can even forget the lead line.” (Williams 1971, 24) In fact, the King Crimson approach appears to be identical in this respect to the Guitar Craft approach mentioned earlier: any note is possible, provided it’s the right one.

Time and again, Fripp has called 1969 a “magic” year in his musical development and in the life of the nebulous collective entity known as King Crimson. The experience was intensely powerful, yet heartbreakingly evanescent. When it was over, that is, when King Crimson I effectively broke up at the end of the year, Fripp was faced with trying to understand what had happened. In 1984 he said, “It was a question of: magic has just flown by, how does one find conditions in which magic flies by? I’d experienced it – I knew it was real. So where had it gone, how could one entice it back? That’s been the process from then till now.” (DeCurtis 1984, 22) Sinfield said it was as though the band had “a Good Fairy. We can’t do anything wrong.” (Fripp quoting Sinfield in Milkowski 1985, 61) Again, Fripp put it this way: “Amazing things would happen – I mean, telepathy, qualities of energy, things that I had never experienced before with music. My own sense of it was that music reached over and played this group of four uptight young men who didn’t really know what they were doing.” (Milkowski 1985, 61)

In the Court of the Crimson King

The residue of this year of magic – the cultural artifact left behind, the spirit of those days frozen into stone (make that vinyl) the enduring physical product resulting from the process – is a long-playing record, released on October 10, 1969, In the Court of the Crimson King: An Observation by King Crimson. A great paradox, a sense of doubt, uncertainty’s edge, surrounds this album and virtually all of Robert Fripp’s recorded music. He will tell you that “If you record or film an event, you spoil it. A live event has a life of its own, it has a quality that you can never capture on record or video. It’s like this: If you’re making love with your girlfriend, the video of the event might bring back nice memories. But the event was something infinitely more.” (Milano 1985, 34) (John Lennon said somewhere, “Talking about music is like talking about fucking. I mean, who wants to talk about it? I suppose some people do want to talk about it …”) Fripp will even go so far as to say that “some of the most amazing gigs I’ve known weren’t ‘musically’ very good. Just listening to tapes afterward … I mean, there’s a real turkey happening. It wasn’t down to notes, it was down to an energy in the room, between the band and the people and the music.” (Fripp 1982B, 58)

What does one make of this? On the one hand, as a musician I too have felt that ineffable energy of really cooking – the music, the musicians, the audience, all in it together, all one – and listening to the tape later, indeed, have had cause to wonder puzzled what the big deal was really all about: it was there, somewhere, but evidently, manifestly, it wasn’t really in the notes themselves. On the other hand, on the negative side if you will, Fripp’s attitude could be seen as a cop-out of sorts: if the residue, the product left behind by the process, is not up to snuff, it’s all too easy to say “My best work has never been recorded and released,” as Fripp frequently does. It’s a clash of philosophies of music we’re dealing with here. Fripp says the music is not in the notes, but rather “music is a quality organized in sound.” (GC Monograph?)

That quality may be there even if the actual (played, sounding) music isn’t anything special from a compositional point of view. Indeed, that quality may be present in a single note, or in silence itself. In the Western tradition of musical composition, these ideas don’t quite make it: at the core of the Western tradition is an accumulation of acknowledged masterpieces, musical scores – testaments, epistles, prophecies – in which it is deemed the hidden knowledge of music resides, to be sought and found and brought to life by the initiate with the right stuff to feel and understand what is really going on there.

Philosophy aside, here we have this piece of plastic, In the Court of the Crimson King, which, in some sense or other, contains the music of the group’s magical year, 1969. The response in the rock press could have been predicted: some writers enthusiastically proclaimed it the music of the future (that is, of the 1970s); macho types endorsed the metal screech of “Schizoid Man” while dismissing “I Talk to theWind” as weak and derivative; comparisons were drawn with the Beatles, Pink Floyd, the Moody Blues, and Procol Harum. Some found the album pretentious, others awe-inspiring.

It is a delight to read the incorrigible Lester Bangs grappling with Crimson’s “myth, mystification, and mellotrons,” subsuming the band’s titanic efforts under his own peculiarly American way of seeing things: “King Crimson would like you to think that they’re strange, but they’re not. What they are is a semi-eclectic British band with a penchant for fantasy and self-indulgence whose banally imagistic lyrics are only matched by the programmatic imagery of their music.” (Bangs 1972, 58)

21ST CENTURY SCHIZOID MAN

(by Fripp, McDonald, Lake, Giles, and Sinfield). Ominous night sounds. An in-your-face metal phrase. Lake screaming the lyrics, voice electronically fuzzed. “Cat’s foot iron claw / Neuro-surgeons scream for more / At paranoia’s poison door / Twenty-first century schizoid man.” Long blisteringly fast instrumental solo section, then unisons at unreal tempo. Grinding downshift to metal lick, final verse, free noise, and out. What can be said about “Schizoid Man” after all these years? It instantly became Crimson’s signature, their anthem, their opener, their war-horse, their sine qua non – a mixed blessing, like Dylan’s “Blowin’ in the Wind,” since for years afterward, it was all many people came to hear Crimson for.

It set up expectations, it put the band in a box: “Why can’t you do more stuff like ‘Schizoid Man’?” Perhaps the song succeeded in giving Fripp’s public iconic persona a certain authority – it established his masculinity, it made a man out of him. Thereafter he knew you knew he could stand in and thrash with the heavies; having proved that, he could go on and tackle other worlds.

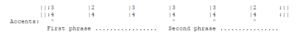

Consider the meter. Count out the number of beats in the opening metal phrase: sixteen. But good luck feeling the music in terms of four bars of 4/4: the accents are all off. To write it out, the best way might be with measures of three, two, three, three, three, and two beats. This way at least the two sub-phrases begin on downbeats:

Fine and good. But now go ahead and try counting the whole thing as four measures of 4/4: if you succeed, and simultaneously feel the accents of the music itself (which are not for the most part coinciding with your counting) you are ipso facto in the realm of Frippian polymeter, revealed here in the very first King Crimson song.

Composition in broad gestures (bold, angular melodic profiles, striking textural contrasts, clear-cut formal schemes, sharply differentiated contrapuntal planes); overpowering intensity of conception and execution; meter and tempo changes, metrical modulation within a single piece; the fuzzy, sustained-note-type guitar lead, along with a tendency to use either very many or very few notes; concrete sound sources (the night sounds at the beginning); a passion for frenetic group sound/noise layers (at the end) … it is remarkable how many stylistic traits we would later come to recognize as characteristically Frippian are packed into this germinal piece.

So … is this what Hendrix would sound like playing Bartok?

“Schizoid Man” floors you (the metal riff), terrifies you (the sung verses), tries as hard as it can to dazzle and impress you (the fast instrumental section), does it all again, and then blows itself to smithereens … and leads without a break into “I Talk to the Wind” …

King Crimson I Live

King Crimson played seventy-eight official gigs in 1969, beginning with a show at London’s Speakeasy on April 9. The group played fifty-eight additional British gigs from April to October; Crimson’s first American tour took place in November and December. During this tour they shared the bill with many of the leading groups of the day: Al Kooper, Iron Butterfly, Poco, the Band, Jefferson Airplane, Joe Cocker, Fleetwood Mac, the Voices of East Harlem, the Chambers Brothers, the Rolling Stones, Johnny Winter, Country Joe and the Fish, Janis Joplin, Sly and the Family Stone, Spirit, Grand Funk Railroad, Pacific Gas and Electric, the Nice, and others. By many accounts, King Crimson out-heavied them all.

Robert Fripp would always contend that King Crimson, in all of its incarnations, was a live band first and a recording-studio band only secondarily. He has never expressed unqualified endorsement of any King Crimson record, insisting, like Bob Dylan, that the whole point for him has been making contact with a real audience in real time. Early on, in 1971, Fripp stressed the importance of crowd feedback, of “a feeling of involvement with the audience.” (Williams 1971, 24) Paradoxically, audience members at Crimson concerts have often felt Fripp to be distant, removed, unresponsive – locked in a world of his own, making few efforts to engage them directly. This perception was reinforced by his practice, adopted after only the first eight gigs in 1969, of sitting on a stool onstage while performing.

When interviewers would ask him, “Why do you sit down on stage?,” Fripp would respond, “Because you can’t play guitar standing up. At least I can’t.” He felt it wasn’t his “job to stand up and look moody. My job was to play, and I couldn’t play standing up.” (Rosen 1974, 18) It was a matter of concentration: “There are some things that are far easier to play standing up, and if it’s a very physical thing that’s required, you don’t want to be anchored too much, whereas if it’s something which requires a fair amount of concentration and technique you can sit down and just concentrate on it.” (Williams 1971, 23-4) But it was also a matter of Fripp’s rejecting what he called the “show biz thing,” the specter of empty gestures in the name of entertainment that forever haunts rock performances. He said wryly, “I can see the beauty of Emerson, ligging about the organ, but I could never do it and make it work satisfactorily. It’d look false, because that’s not the kind of bloke I am.” (Williams 1971, 23)

Consider something John Lennon said in 1970: “The Beatles deliberately didn’t move like Elvis, that was our policy, because we found it stupid and bullshit. And then Mick Jagger came out and resurrected bullshit movement, you know, wiggling your arse and that. So then people began to say, ‘Well, the Beatles are passe because they don’t move.’ But we did it as a conscious thing.” (“Lennon Remembers,” 34)

I TALK TO THE WIND

According to the album credits this is not a Fripp piece; it was written by Ian McDonald and Pete Sinfield. I always had trouble with this song: it seemed to take a long time (five minutes and forty seconds) to say not much of anything. There is some beautiful linear counterpoint – that is to say, the harmonies result from the directional leading of individual melodic lines – and the gentle clash of major and minor modes is poignant enough. But in the final analysis the value of “I Talk to the Wind” has more to do with its formal function on Side A of the record than with any intrinsic musical merit: you’ve got to have something soft and seductive between “Schizoid Man” and “Epitaph.” An idyllic interlude between the rape and the prophecy. I’m just not sure it had to be this long. “I Talk to the Wind” leads without a break into “Epitaph” …

Judging from concert reviews of the 1969 British and American tours, King Crimson had a way of flattening audiences and upstaging the acts it was supposed to be supporting. (Fripp reports that the Moody Blues refused to undertake a joint tour with King Crimson: he says Graham Edge of the Moodies felt that King Crimson “were simply too strong.” [YPG, 2]) The music was loud, it was powerful, it was gut-wrenching, it was an unbelievable wall of sound. Melody Maker writer Alan Lewis reported on the concert King Crimson did with the Nice at Fairfield Hall in Croyden on October 17: Crimson played “21st Century Schizoid Man,” “Epitaph,” “Trees” (never recorded), the “incredibly heavy” “Court of the Crimson King,” and closed with “Mars” from Holst’s Planets suite, “hammering out the menacing riff over an eerie wail from Ian McDonald’s mellotron.

Together with Peter Sinfield’s brilliant lights, they created an almost overpowering atmosphere of power and evil.” (Lewis 1969, 6) In Lewis’s view, the classical/rock menagerie of the Nice was no match for Crimson’s aggressive presence. In the nascent world of progressive rock, perhaps Keith Emerson was the movement’s McCartney, Robert Fripp its Lennon – the Lennon of the primal scream.

Similarly, Chris Albertson, reviewing for Down Beat a Fillmore East (New York) concert in November where King Crimson opened for Fleetwood Mac and Joe Cocker, judged that Crimson was “clearly the superior group and all that followed was anti-climactic.” Albertson noted the quality of the group’s material, the extraordinarily high level of musicianship, the collective improvisation, and the jazz influence, concluding, “King Crimson has majestically arrived, proving that neither the Beatles nor Stones were the last word from England.” (Albertson 1970, 20-21)

Only a few months after their formation, King Crimson were being placed in fairly heady company. E. Ochs sketched his impressions of KC I live at the Fillmore East for Billboard readers: “King Crimson, royal relative and fellow heavy to Deep Purple, outweighed Joe Cocker and Reprise’s Fleetwood Mac 10 tons to two … when the new Atlantic group clashed ear-splitting volume with well-integrated jazz, yielding a symphonic explosion that made listening compulsory, if not hazardous …

King Crimson can only be described as a monumental heavy with all the majesty – and tragedy – of Hell … King Crimson drove home the point of their musical philosophy with the volume turned up so high on their amplifiers that, had they been electric blankets, they would have all broiled to death. Not to mention third-degree burns in the audience. The group’s immense, towering force field, electrified by the energy of their almost frightening intensity, either pinned down patrons or drove them out.” (Ochs 1969, 22)

EPITAPH including MARCH FOR NO REASON and TOMORROW AND TOMORROW

(by Fripp, McDonald, Lake, Giles, and Sinfield). The Gothic rock ballad is born. Slow gloomy minor key mellotron-rich. Sinfield’s text meditates pessimistically on the failure of old truths to bring meaning into contemporary existence (“The wall on which the prophets wrote / is cracking at the seams”), on the threat posed by the proliferation of technological means unchecked by a guiding moral vision (“Knowledge is a deadly friend / when no one sets the rules”), and on the bleak prospects the future holds (in the words of the refrain, “Confusion will be my epitaph / as I crawl a cracked and broken path / If we make it we can all sit back and laugh / But I fear tomorrow I’ll be crying”).

It gets down to what you can say in a slow (positive: deliberate, stately, majestic … negative: plodding, interminable, insufferable) rock song. Fripp has always contended that rock is our most malleable contemporary musical media: that you can say anything with it. Crimson was obviously going for the Big Statement here. Maybe Sinfield bit off more than he could chew; some of his metaphors are on the labored side, in danger of collapsing under their own weight: “… the seeds of time were sown / and watered by the deeds of those / who know and who are known.” It may not be Shakespeare, but the lyrics are really no more grandiose than the music, and in 1969 there was still an innocence about efforts like this to combine classical gigantism with rock, romantic lyric poetry with repetitive rock melodic types.

Consider the long fade-out: the progression VI-v in the key of E minor repeated eighteen times to gloomy vocalizations and clanging electric guitar dissonances. The harmonic domain is thus modal – in effect, B-Phrygian. Whether or not it was Fripp who contributed this modal chord progression, he was increasingly to draw on modal vocabulary in subsequent works, as an alternative to traditional major/minor tonality.

Fripp’s guitar work: electric guitar is used at selected points of emphasis, but the primary guitar sound is acoustic strumming and arpeggiation: like virtually all of Fripp’s “rhythm” guitar work, it never falls into incessantly repeated strumming patterns, but rather is animated by a highly imaginative textural instinct.

Consider, too, the minor tonality. Minor. Minor. It has to be minor. All the songs on In the Court of the Crimson King are in minor, except “I Talk to the Wind,” which is sort of in minor, but veers major at cadence points. Minor: traditionally the mode of sadness, regret, the dark side of life, despair, anger, sorrow, angst, depression, uncertainty, pathos, bathos, bittersweetness, ending, finality, death.

For all its minorishness, “Epitaph” is completely conventional harmonically, and sounds indeed harmonically rather than linearly conceived. I don’t know if it was Fripp who came up with the chord progression. But as his development progressed, he became less attached to traditional functional harmony; his textures became increasingly contrapuntal (with complex figurations of a harmonically implicative rather than declamatory nature replacing homophonically-conceived chord progressions); and in general rhythm, melody, texture, and timbre took precedence over harmony as the most significant purveyors of musical meaning.

For Fripp, Lake, McDonald, Giles, and Sinfield, touring had its hazards. At the focal point of the tremendous energies being unleashed, the band, according to Melody Maker reporter B.P. Fallon, would “admit to being physically and mentally shattered” at the end of a performance. (Fallon 1969, 7) Giles wrote a column for the same British magazine, describing the rigors of playing America’s large venues, meetings with other musicians, and the endless waiting that accompanies road life; there is an undertone of despair in his prose, even as he describes future projects King Crimson was discussing, such as writing, performing, and possibly recording a “modern symphony” for twelve or so “leaders in modern musical attitudes.” (Giles 1969, 23)

The impression is that even on the road, the members of the group at times had access to a furious white-hot creative maelstrom. On the other hand, the primary challenge seems to have been simply to avoid boredom and stay in touch with the music. Fripp indicated there was only one way he could keep himself together: “My answer to American hotel life was to put the TV on and practice for eight hours a day.” (Williams 1971, 24)

It was perhaps inevitable that the strains would rip the group apart. By the end of December, Mike Giles and Ian McDonald had officially announced their departure from King Crimson. Giles was quoted as saying: “I felt that sitting in a van, an aeroplane and hotel rooms was a waste of time even if you are getting a great deal of money for it. Ian and I feel that we’d rather have less money and do more creative, interesting and fulfilling things with all the travelling time. The main thing is for Ian and I to write and record using musicians of similar attitude with the accent on good music – really doing what we feel we should be doing with a lot of emphasis on production.

Part of the reason for the split was that I didn’t feel I could do this within King Crimson and they need the freedom to follow through what they need to do.” (Eldridge 1970, 13) Sinfield thought the split had to do with personalities: Lake and Fripp were by nature “strong, very forceful, almost pushy,” while McDonald and Giles were “very, very receptive.” Sinfield, who felt his personality was somewhere in the middle, said that the combination of the five “could and did work to a degree but the pressure got too much for Ian and Mike.” (Eldridge 1970, 13) For his part, McDonald expressed dissatisfaction with the overall tone of the music as it had developed. The gloom-and-doom aspect, he had decided, was not him: “I want to make music that says good things instead of evil things.” (Nick Logan, “Replacements,” NME (Jan. 24 1979), quoted in YPG, 7)

On December 7th, after four dates on consecutive nights at Hollywood’s Whisky A Go Go, McDonald and Giles told Fripp of their decision to leave. Fripp’s reaction appears to have been shock: “My stomach disappeared. King Crimson was everything to me. To keep the band together I offered to leave instead but Ian said that the band was more me than them.” (YPG, 6) Fripp’s view was that King Crimson had taken on an autonomous life of its own; it was an idea, a concept, a way of doing things, a channel, a living organism; music had spoken through it. He put it simply: “King Crimson was too important to let die.” (Crowe 1973, 22)

MOONCHILD including THE DREAM and THE ILLUSION

(by McDonald and Sinfield). Twelve minutes and nine seconds. You see, the thing is, I’ve been in jams like this. The feeling is totally there among the musicians (and whoever else happens to be sitting around, whether they’ve paid for it or not, probably, and preferably, not). You are close to silence, Silence with a capital S. You are in tune with silence, the deepest sound of them all. Every sound, therefore, that you make, make with intention, sensitivity, and awareness, has a meaning, an ineffability, a significance. You are listening, Listening with a capital L. You hear what everyone else is doing; you do whatever is necessary, which is usually as little as possible. It has nothing to do with self-expression: it has to do with a group mind. And yes, it is possible to become a group mind, to feel that sense of immersion in something so immeasurably greater and lighter and more sensitive and more conscious than your own paltry, complex-ridden, neurotic, solipsistic, pathetic self.

And no, such moments cannot really be anticipated and made to happen (although one can gain a certain expertise at setting up the conditions for them to happen). And yes, when those moments do happen it is all enough, the music, the sense of the music happening as it were of its own will and to its own purposes – you are in tune with the vibration of nature itself, you are its instrument – it is playing you and you are merely the rapt spectator of this spectacular play of sound in all its parameters which seem so lucidly there, so transparent, so available, all you have to do is stretch out your hand to feel its warmth, its fullness, its loving and terrifying infinity, there is nothing else you need or ever will need.

BUT – but: … the bitch of it all is that you put some of this stuff on tape and it just sounds like the most unbelievably aimless doodling, like the random toning of the wind chimes blowing on your front porch, or traffic noises outside your window. THEN you are faced with a philosophical bugaboo. Because, you see, music, in its very essence, is too great, too vast, too intangibly infinitesimal, too subtle for human conception. You are stuck with the sense that you might as well contemplate the sound of that wind chime on your porch, or listen to the screen door’s periodic groans and slams, or listen to the sound of your own breathing, or the silent sound of your own thoughts as they careen through the blank void of your pathetic awareness – you might as well do that as listen to this horrid tape you have made or to the residue of some 1969 studio session by five horrid British rock musicians called King Crimson. And well you might.

As it happens, a few of “classical music”‘s twentieth-century pantheon of composers were already hip to all this, and endeavored to enlighten recalcitrant audiences through their outrageous acts, pieces, ideas, concepts, noodlings, doodlings, and explications

One was the American John Cage, (whose final position was, and is, that “everything we do is music”) whose “silent” piece, 4’33” enraged some and entranced others as far back as 1952 (the unavoidable implication of 4’33” was that the sounds heard when attempting to listen to nothing were just as interesting as any Beethoven masterpiece), who devised methods of composing by chance so the “composer” could get his pathetic personality out of the way and let the perhaps ordered, perhaps random laws of nature speak for themselves – just like the wind chimes.

Another was the German Karlheinz Stockhausen, who took a more psychological, more practical approach, for instance in his 1968 “composition,” Aus den sieben Tagen (From the Seven Days). This is a set of prose instructions for musicians (or I suppose anyone) to follow in order to have a quality musical experience. Among the fifteen “pieces” in Aus den sieben Tagen, perhaps the most extreme is “Gold Dust,” which reads as follows: “Live completely alone for four days / without food / in complete silence / without much movement / sleep as little as necessary / think as little as possible //after four days, late at night / without conversation beforehand / play single sounds // WITHOUT THINKING which you are playing /// close your eyes / just listen.” (Stockhausen, 7 Tagen, ?) But perhaps more pertinent to our discussion of King Crimson 1969 is “It,” the piece just before “Gold Dust” in “Aus den sieben Tagen.” The instructions for “It” read: “Think NOTHING / wait until it is absolutely still within you / when you have attained this / begin to play // as soon as you start to think, stop / and try to re-attain the state of NON-THINKING / then continue playing.”

What would such music sound like? You do not have to guess. “It” was recorded by Deutsche Grammophon in 1968 and you can hear it for yourself. But in case you don’t have access to old German pressings (though the record is readily available in most university music department record libraries), it doesn’t matter much. It sounds much the same as King Crimson’s “Moonchild.”

THE COURT OF THE CRIMSON KING including THE RETURN OF THE FIRE WITCH and THE DANCE OF THE PUPPETS

(by McDonald and Sinfield). Along with “Epitaph,” this is the album’s other mellotron epic. The title track. Hence theme song/anthem for the laddies in the group’s early stages, though decidedly nothing like “Here We Come, We’re the Monkees.” Because it is not a Fripp composition, I will pass it over rather quickly here, except to note: the rather foursquare phraseology, which it would take Fripp a while to get away from; the ubiquitous minor modality; the false (major) ending, as in “I Talk to the Wind”; the odd circus-music woodwind/organ break after the false ending – one of those stark, unreasonable textural/associative contrasts which Fripp was to employ so effectively in later efforts; the Gothic heaviness of it all; and finally the abrupt ending – after having built up a whole album’s worth of momentum, a melodramatic climax is avoided in favor of a sort of musicus interruptus

* * * * * * * * * * * *

In retrospect, whatever one felt about this music, the seminal nature of the album cannot be denied: the variegated yet cohesive In the Court of the Crimson King helped launch, for better or for worse, not one but several musical movements, among them heavy metal, jazz-rock fusion, and progressive rock. As the Rolling Stone Record Guide was to put it some years later, the album “helped shape a set of baroque standards for art-rock.” (RS Record Guide, 1st ed., 204)

King Crimson II

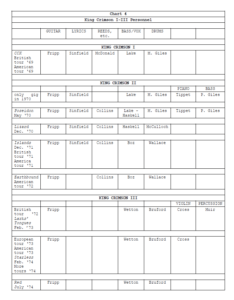

After the breakup of King Crimson I in December 1969 a period of some two and a half years ensued during which Fripp struggled to keep Crimson alive and in some sense intact as a recording band, performing outfit, and concept. To make the almost continual personnel changes of this and the following period easier to visualize, I have concocted the chart which appears on page 40.

Looking at the period 1970 to early 1972 – King Crimson II as we are calling it – at a distance of nearly two decades, this writer has rather violently mixed feelings about it. It didn’t take Fripp long to figure out that somehow the music had lost its course. As early as 1973 he was talking about King Crimson II like this: “The time was spent preparing for the present, I suppose. This band [King Crimson III] is right for the present, just as the first band was right for its own time. The interim period was something I wouldn’t want to undergo again.” (Crowe 1973, 22) And in 1978 he admitted being “embarrassed” by KC II: “I went into catatonia for three weeks on a tour with that incarnation of the band. It was one of the most horrible periods of my life.” (Farber 1978, 27)

During the period itself, with musicians entering and exiting the Court at a rapid pace, with ideas flying by, attempts being made to catch them, improvisational situations being tried out, albums being made, Fripp did his best to put the best face on it. In 1971 he said, “The beauty of the set-up in Crimson is that it can handle having a flexible personnel around a “core” of more or less permanent members” – the core, getting right down to it, being Fripp and Sinfield, and ultimately Fripp alone. (Williams 1971, 24) At the least, Fripp was able to indulge his perennial fascination with “the way musicians work together as a unit. You see, I view King Crimson as the microcosm of the macrocosm.” (Crowe 1973, 22) By which one feels he meant that being in an evolving, complex, unpredictable, perilous yet potential-laden musical situation like King Crimson was verily analogous to being alive on planet Earth, or like being in some alchemical laboratory (the microcosm) for the purpose of investigating life itself (the macrocosm).

Fripp would also issue elliptical, contradictory, unfathomable statements concerning his exact role in King Crimson. On the one hand, it was obvious by the end of 1972 that he was the only person who had been in all of the band’s incarnations, that in some sense King Crimson was Robert Fripp plus whoever, that it was his band. Yet he seemed to shrink from assuming unambiguously the mantle of authority, which he felt belonged not to him but to King Crimson itself, the concept, the idea, the force, the music, not to one or several particular merely human personalities. In 1973 he would say things like, “I form bands, but I’m not a leader. There are far more subtle ways of influencing people and getting things done than being a band leader. Although I can be a band leader, it’s not a function I cherish. Who needs it?” (Crowe 1973, 22)

In the Wake of Poseidon and Lizard

In January 1970, after the departure of McDonald and Giles, King Crimson was temporarily a trio consisting of Fripp, Lake, and Sinfield. (McDonald and Giles went on to make their self-titled duo album, released in 1971; McDonald was subsequently one of the founding members of Foreigner in 1976.) The trio cancelled future gigs and set about composing, rehearsing, and looking for new members to fill out the group, with vague plans to resume live performances. In order to sustain public interest in the band, King Crimson released the single “Cat Food / Groon” on March 13.

King Crimson’s only gig in 1970 was an appearance on BBC TV’s “Top of the Pops” program on March 25, performing “Cat Food” with the lineup listed in the chart on page 40. By the end of the month Crimson had auditioned several drummers with the intent of finding a permanent replacement for Michael Giles but had succeeded only in enlisting the services of Circus’s flute and reed player Mel Collins. In early April, bassist/vocalist Greg Lake decided to leave the Court and form a band with the Nice’s Keith Emerson: this was, of course, the nucleus of the mighty Emerson, Lake, and Palmer. In the meantime, Fripp and the whole motley crew mentioned in the last couple of pages, in various combinations, had been busy recording In the Wake of Poseidon, King Crimson’s second album, which was released in May.

Islands and Earthbound

The period immediately after the release of Lizard was what Fripp has called “a time of desperation.” (YPG 11, Dec. 19 1970) King Crimson was looking for bassists and singers, and considered Bryan Ferry, among many others. After Fripp had auditioned some thirty bass players, Boz Burrell was chosen in February 1971. Or rather, it appears that having been selected as King Crimson’s singer, Boz (who was not a bassist) was one day noodling around on a bass and Fripp decided it would be possible to teach him to play the instrument, more or less from scratch. With the lineup of Fripp, Sinfield, Collins, Boz, and Ian Wallace (drums), King Crimson rehearsed through March and by April were ready to start performing, it had been almost a year and a half since the end of the American tour in December 1969, when King Crimson I broke up, and Fripp was nervous but exceeding eager.

After four April dates at the Zoom Club in Frankfurt, the band began a long and grueling tour schedule (1971 – Britain: May, fourteen gigs; June and July, two gigs; August, seven gigs; September, six gigs; October, eighteen gigs. Canada and U.S.A.: November, twelve gigs; December, six gigs. 1972 – U.S.A.: February, twelve gigs; March, nineteen gigs; April, one gig). The touring band drew on King Crimson’s by now fairly substantial repertoire.

(Historical footnote on the pecking order among British progressive rock bands in late 1971: at two concerts at the Academy of Music in New York on November 24 and 25, Yes opened, King Crimson played second, and the headliner was Procol Harum. The Variety reviewer, who noted the undue time necessary for equipment changes between sets by the three quasi-symphonic behemoths, allowed that Procol Harum was “in fine form” but “was put to the test by having to follow strong sets by Yes and the overpowering King Crimson,” who, he felt, “should headline next time out.” When King Crimson returned to the Academy of Music on February 12, 1972, they were indeed the headliners – supported by Redbone and the Flying Burrito Brothers.)

In the meantime, work was in progress on the studio album Islands, which was completed by October and released on December 3, 1971, almost exactly a year after “Lizard.” All of the album’s six pieces were by Fripp or by Fripp and Sinfield. Fripp used the contributions of nine musicians to get the sound he wanted, but if King Crimson was a way of doing things, for Islands that way involved following Fripp’s instructions to the letter. As drummer Wallace has testified, “Fripp was in one of his weird periods. You had to play everything the way he did it. There was no room to stretch out.” (Rosen 1983, 21)

As for Sinfield’s lyrics – well, let me let another writer carry out the execution. Don Heckman, reviewing Islands in Stereo Review: “What is there to say, after all, about lyrics that go ‘Time’s grey hand won’t catch me while the sun shine down / Untie and unlatch me while the stars shine,’ or ‘Love’s web is spun, cats prowl, mice run / Wreathe snatch-hand briars where owls know my eyes’? … With Yeats and Thomas and Keats and Lord knows how many other superb English poets available to me, I bloody well don’t intend to waste my time with absurdities like this.” (Heckman 1972, 101)

One of the strangest “rock” albums ever released, Islands presents stark, unreasonable contrasts: the three excessively precious and poetic ballad-type songs “Formentera Lady,” “The Letters,” and “Islands” (all of which nevertheless continue to use highly imaginative textures); the fantastic raunchy profundity of the guitar showcase instrumental “Sailor’s Tale”; the X-rated “Ladies of the Road”; the pure if not puerile classicism of “Prelude: Song of the Gulls”; and the oceanic spaciousness of the title track, “Islands.” Of all of Fripp’s albums, this is probably the hardest to understand, the easiest to ridicule, the most difficult to be generous to. And yet …

ISLANDS

The last thing we hear on Islands, after a lengthy silent interlude following the final song, is the chamber group used for “Prelude: Song of the Gulls” tuning up and the soft yet persuasive voice of Robert Fripp telling them they’re going to do it twice more, once with the oboe and once without, then call it a day. He counts off the beat, one-two-three two-two-three, and … silence: Islands is finished. I suppose you can read into this whatever you want, but to me it seems as if Fripp is telling us (the audience), Look, this is music, and music is made by people, and people have to tune up and practice and rehearse, and there is so much more behind music than the sound, more than ever can be told.

For all its impenetrability, its self-conscious artistic excess, its woefully labored attempts to capture innocence, there is a certain quality in Islands making the sum much greater than its parts, even if this sum does not quite tally up to musical greatness. The strange thing is, I listened to the album today for the first time in a couple of years, and I found, almost against my will (since I’ve been telling people for some time that Islands is the absolute worst King Crimson record ever put out) – I found that I actually liked it. As an overall musical gesture. The whole album has that sort of fin-de-siecle manneristic feeling, like the over-refined music of the late fourteenth century, the twilight of the middle ages – a sense of worlds falling apart, new ones as yet unborn, grand heartbreaking nostalgia for what can no longer be, rough beasts slouching toward Bethlehem to be born.

In the composition of Islands, Fripp was learning to subtract, to take things away, to let the black backdrop of silence show through the music, to heed the oft-repeated but ill-practiced axiom that less is more. To borrow a phrase from Eno (who in turn derived it from filmmaker Luis Bunuel): “Every note obscures another.” (Grant 1982, 29)

As had King Crimson’s American tour in late 1969, their American tour in November and December 1971 produced many moments of tension and even hostility among the band’s members. Sinfield – who on tour played VCS3 synthesizer and worked the group’s lighting and sound – in particular found the turmoil and pressures of being on the road in America difficult to cope with, and made up his mind that he wouldn’t return to the States again with the band “unless specific conditions were fulfilled, and I didn’t expect them to be.” (YPG 18, quoting Williams, MM, Jan. 8 1972) It wasn’t long before Sinfield and Fripp had reached a point where it became clear that they were moving in irreconcilably different directions.

On New Year’s Day 1972, the New Musical Express (YPG 17) reported that Sinfield had left King Crimson, and a week later Fripp explained his view on the matter: “I suppose that the thing to say is that I felt the creative relationship between us had finished. I’d ceased to believe in Pete … It got to the point where I didn’t feel that by working together we’d improve on anything we’d already done.” (YPG 18, quoting Williams, MM, Jan. 8 1972) As usual with Fripp, his dealings with the outer world were intimately bound up with his inner development. Eight years after the split with Sinfield, Fripp explained to an interviewer that he came to the decision to make the break on the same day he changed the name he was known by from “Bob” to “Robert”: “I felt I’d made my first adult decision.” (Watts 1980, 22)

Sinfield had had increasing difficulties dealing with his position in King Crimson, especially on tour. Fripp said that “the band often found the lights distracting”, (YPG 18, quoting Williams, MM, Jan. 8 1972) he himself had grown suspicious of the visual “trickery” associated with the British tour of 1971, “however fine it may have been. I’m thinking of the lights, and the general blood and thunder.” (YPG 18-19, quoting MM, Jan. 15 1972) In other words, Fripp wanted the band to be judged on its purely musical merits – again the suspicion of the “show biz” aspect of rock and roll performance.

For his part, Sinfield, who had nevertheless expressed a desire to let his work grow in directions other than those offered by the King Crimson format, regarded the decision for him to quit the group as “entirely on Bob’s side”: “Bob rang me up and said ‘I can’t work with you.’“ (YPG 18, quoting Williams, MM, Jan. 8 1972) Fripp was at pains to present the split to the British press in the most rancorless possible terms, and was disturbed by the sensationalist manner in which the New Music Express handled it. (YPG 18, Jan. 8 1972) The many instances of press distortion involving King Crimson constituted one reason why, later in the 1970s, Fripp would undertake a one-man campaign to reject and re-write the ground rules of the whole music industry complex.

In the opening months of 1972 the remaining members of King Crimson – Fripp, Collins, Boz, and Wallace – were not exactly congealing into what one would describe as a happy family. Yet, as reports of inner dissent came out in the press, the band was booked for one more American tour. As Fripp was later to write, the “Earthbound” tour “was conducted in the knowledge that the group would disband afterwards.” (Fripp 1980F, 38)

While in America on KC II’s final tour (February-April 1972), drummer Ian Wallace bought a portable Ampex stereo cassette deck which the group plugged into the mixing board during live performances. Many performances were taped this way, and Fripp subsequently took the cassettes home and edited them down to a live album, Earthbound, released in England on June 9, 1972. Crimson’s American distributor, Atlantic, declined to put out the record, saying the sound quality wasn’t good enough. (My copy is a later Italian version on the Philips/Polydor label, featuring liner notes by a certain Daniele Caroli titled “Robert Fripp: musica psichedelica dal vivo negli USA” [“live psychedelic music in the USA”] and incongruously sporting a cover collage utilizing the photos from King Crimson’s 1974 album Red: Fripp, John Wetton, and Bill Bruford., Sound quality or no sound quality, Earthbound is an unusual cultural document, the sole officially released record of KC II live, music somehow emerging from the wreckage of a dream.

EARTHBOUND

The contrast between Islands and Earthbound is extreme to a degree, a bit like mentioning Judy Collins and Patti Smith in the same breath. The split between studio Crimson and live Crimson had grown virtually to the point of schizophrenia: there was Fripp the painfully self-conscious composer of delicate neo-romantic refinements, refined almost to a point of transparently pellucid non-entity; and there was Fripp the jagged metal warrior, brazenly brandishing his electric guitar as a weapon, band of sonic renegade vagabonds in tow. Great musicians often have some such split musical personality – Beethoven can pat you lovingly on the cheek one minute, and wheel you around and kick you in the butt the next.

King Crimson II: a period of intensive searching by Robert Fripp, who managed, in trying circumstances, some of which were surely of his own (if unconscious) making – to put out four albums of some of the most experimental, eclectic, interesting, difficult, challenging, beautiful, ugly, and at times profoundly irritating music ever to come out of the rock orbit.

Listen to: King Crimson – 21st Century Schizoid Man

Robert Fripp–guitar Ian McDonald–reeds, woodwind, vibes, keyboards, mellotron, vocals Greg Lake–bass guitar, lead vocals Michael Giles–drums, percussion, vocals Peter Sinfield–words and illumination

Cover by Barry Godber

Equipment by Vick and Dik

Recorded at Wessex Sound Studios, London Engineer: Robin Thompson Assistant Engineer: Tony Page Produced by King Crimson for EG Productions, ‘David & John’

Lyrics:

Cat’s foot iron claw

Neuro-surgeons scream for more

At paranoia’s poison door.

Twenty first century schizoid man.

Blood rack barbed wire

Polititians’ funeral pyre

Innocents raped with napalm fire

Twenty first century schizoid man.

Death seed blind man’s greed

Poets’ starving children bleed

Nothing he’s got he really needs

Twenty first century schizoid man.

Download the best Rock sheet music from our Library.

Browse in the Library:

Or browse in the categories menus & download the Library Catalog PDF: