Come join us now, and enjoy playing your beloved music and browse through great scores of every level and styles!

Can’t find the songbook you’re looking for? Please, email us at: sheetmusiclibrarypdf@gmail.com We’d like to help you!

Philip Glass: Glassworks (arr. for piano & sheet music)

Glassworks is a chamber music work of six movements by Philip Glass. Following his larger-scale concert and stage works, Glassworks was Philip Glass’s successful attempt to create a more pop-oriented “Walkman-suitable” work, with considerably shorter and more accessible pieces written for the recording studio. In fact, the cover of the cassette release stated that it was “specially mixed for your personal cassette player”.

The album was released in 1982.

Glassworks was intended to introduce my music to a more general audience than had been familiar with it up to then.

— Philip GlassMovements

- “Opening” (piano, with horn at end) 6:24

- “Floe” (2 flutes, 2 soprano saxophones, 2 tenor saxophones, 2 horns, synthesizer) 5:59

- “Island” (2 flutes, 2 soprano saxophones, tenor saxophone, bass clarinet, 2 horns, viola, violoncello, synthesizer) 7:39

- “Rubric” (2 flutes, 2 soprano saxophones, 2 tenor saxophones, 2 horns, synthesizer) 6:04

- “Façades” (2 soprano saxophones, synthesizer, viola, violoncello) 7:20 This movement has its origins in the film score Koyaanisqatsi, but was ultimately not used in the film; it is often performed as a work in its own right (ISWC T-010.461.089-0).

- “Closing (flute, clarinet, bass clarinet, horn, viola, violoncello, piano) 6:03 A reprise of “Opening”.

(From Wikipedia).

Musical analysis (harmony and motive reviews)

Writings that are directly related to Glassworks are found in a section of the book Music by Philip Glass by Philip Glass, Music by Philip Glass, a webpage from the official website of Philip Glass, and a conference paper by Evan Jones (“The ‘Content and Flavor.’) Philip Glass introduces recording processes in his book Music by Philip Glass; the recording processes involve digital recording and computer-processed mixed tapes. On the Glassworks’ webpage of Glass’s official website, Glass states that Glassworks is a six-movement piece composed for a recording studio that he intended to introduce to a more general audience.

In his paper, Evan Jones focuses on harmonic cycles in Philip Glass’s works composed between the years of Another Look at Harmony (1975) and the works of the late 1980s. Jones applies the idea of harmonic cycles to his analysis of the third movement “Island” of Glassworks.

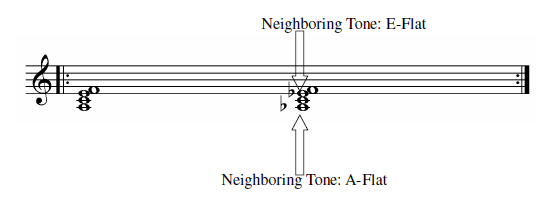

A harmonic cycle involves two or more chords which are constantly being repeated in turn. In Jones’s harmonic analysis of the third movement, two types of harmonic cycles are indicated. The first type of harmonic cycle

involves a chord, and its neighboring tones in the next chord. See Example 1.

In Example 1, the first chord F Major/Major 6/5 chord, and the second chord F Minor/Minor 6/5 chord alternate to form the first type of Jones’s harmonic cycle. The notes a-flat and e-flat1 in the second chord are both lower neighbor notes to the notes a-natural and e-natural1 in the first chord.

Therefore, for Jones, the harmonic cycle involves chords with neighboring tones.

The second type of harmonic cycle includes what Jones calls “diatonic drift.” Jones makes a distinction between what he interprets as “seen” as “heard.” I will not go into detail on these points because they do not contribute to my approach.

Philip Glass’s use of harmonic and motivic patterns are discussed in Robert Fink’s book Repeating Ourselves (Repeating Ourselves: American Minimal Music as Cultural Practice, (Berkeley), Keith Potter’s book Four Musical Minimalists (

Four Musical Minimalists: La Monte Young, Terry Riley, Steve Reich, Philip Glass, (Cambridge, UK), Wes (Wesley) York’s article “Form and Process,” Milo Raickovich’s dissertation “Einstein on the Beach by Philip Glass: A Musical Analysis,” and Rob Haskins’s online journal article “Another Look at Philip Glass: Aspects of Harmony and Formal Design in Early Works and Einstein on the Beach.” In Repeating Ourselves, Robert Fink relates Philip Glass’s motivic passages in 1+1 (1968) and Strung Out (1967) to Shinichi Suzuki and Shunryu Suzuki’s interpretation of a Zen mind in music.

In Four Musical Minimalists, Keith Potter provides an overview of Philip Glass’s career and the compositional devices of some of Glass’s significant works, such as the additive process in Glass’s 1+1 (1968), Two Pages (1974), Music in Fifths (1969), Music in Contrary Motion (1969), Music in

Similar Motion (1969); and the tonal, pitch structure, and scales in Music in Twelve Parts (1971-74) and Einstein on the Beach (1975-76), one of his famous operas.

In Wes York’s article “Form and Process” in Writings on Glass: Essays, Interviews, Criticism, the processes of the shifts of melodic patterns, melodic expansion, and melodic diminution in Philip Glass’s Two Pages are shown with line charts and musical examples transcribed from a recording of Two Pages.

Milo Raickovich’s dissertation explores the core motive, the use of the pentatonic scales and the harmonic plan of Einstein on the Beach. Rob Haskins’s article “Another Look at Philip Glass” contains the usages of

additive variations in Glass’s early works Two Pages, Music in Contrary Motion, and Music in Similar Motion, and the further application of additive variations in Einstein on the Beach. For Haskins, harmonic designs in Einstein on the Beach include repeated pc sets, set classes, and harmonic cycles.

Writings regarding Philip Glass’s compositional approaches include Anders Beyer’s book The Voice of Music, and the book Soundpieces by Cole Gagne and Tracy Caras.

Both books are written interviews with Philip Glass about his attitudes toward his compositional processes.

Let’s watch how harmonic loops and motivic loops function in all six movements of Philip Glass’s Glassworks. A harmonic loop contains chords that repeat a certain number of times, with a break that stops the loop or shifts the music to a new loop or non-looping material. A motivic loop consists of melodic, intervalic, or rhythmic motives operating similarly.

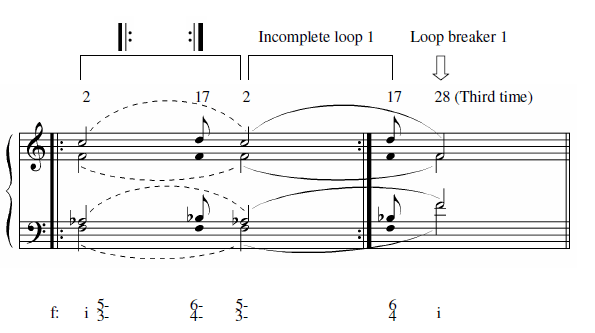

See Example 2 for Harmonic Loop 1 in Glassworks Movement I “Opening”.

In Example 2, loop 1 is formed by an F minor chord with a neighboring

6 4 voice-leading [f, b-flat, f1, d2] and interrupted by the final F unison. Since loop 1 is broken by the F unison, the F unison can be called loop breaker 1.

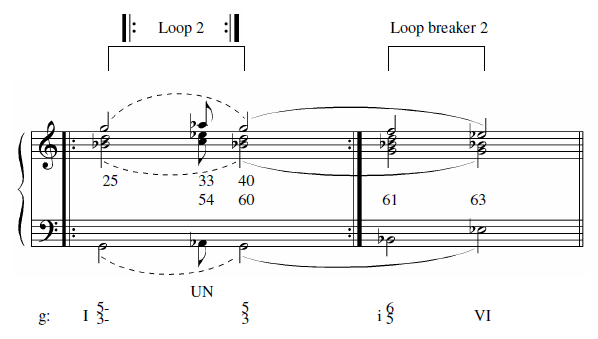

See Exemple 3 got a more complex Harmonic Loop 2 in Glassworks Movement IV “Rubric”:

In Example 3, loop 2 is constituted by a G minor chord with bass moving to the upper neighbor note (UN): A-flat; and the top three voices moving to their upper neighbor notes:

a-flat 2, c2 and e-flat2.

When the designated amount of repetitions of loop 2 is reached, loop 2 is terminated by another loop breaker, loop breaker 2, a harmonic progression of I 6 5 moving to VI (sounding curiously unresolved). In short, harmonic loops in Glassworks can be either interrupted by a unison (as in Example 2), or terminated by a progression of chords (as in Example 3).

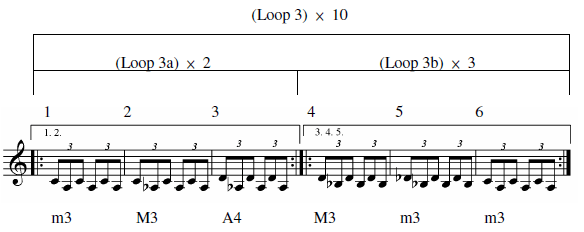

There are two kinds of motivic loops in Glassworks. The first kind is the

interchanges of intervalic qualities. See Example 4a.

Glassworks Movement V “Façades”.

In Example 4a, the motives in loop 3 include six pairs of triplets. Each pair of the triplets contains an interval. The interchanges of intervalic qualities involve the shift of intervalic qualities in both directions: minor third (m3) to major third (M3) from m. 1 to m. 2, and major third (M3) to minor third (m3) from m. 4 to m. 5.

The two major thirds in m. 2 and m. 4 are connected by the pivot note d1 in the largest interval of loop 3 augmented fourth (A4), which can be considered as the climax of loop 3. The minor third (d-flat1 and b-flat) in m. 5 is linked to another minor third (c1 and a) in m. 6, which leads back to the beginning of loop 3.

Therefore, the interchanges of intervalic qualities define loop 3 as an intervalic loop. Another feature in the motivic loop is the loop within loop operation (See Example 4a.)

In Example 4a, loop 3 is a motivic loop that contains two small motivic loops, 3a and 3b. Loop 3a is played two times; loop 3b is played 3 times, and the entire loop 3 is played ten times. Both Loop 3a and Loop 3b are partly symmetrical, as in mirror images.

The intervals of the first two measures in loop 3a are minor third (m3) and major third (M3). The intervals of the first two measure of Loop 3b are major third (M3) and minor third (m3). Furthermore, the operation of loop 3 can be represented by a mathematical equation.

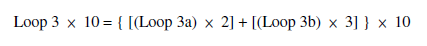

See Example 4b.

Glassworks Movement V “Façades”.

In the 12 equation, Loop 3 × 10 indicates that loop 3 are played 10 times, (Loop 3a) × 2 indicates that loop 3a is played 2 times, and (Loop 3b) × 3 indicates that loop 3b is played 3 times.

The sum of (Loop 3a) × 2 and (Loop 3b) × 3 is repeated 10 times. The equation in Example 4b shows the additive and multiplicative effects of Loop 3, Loop 3a, and Loop 3b.

It seems that the harmonic loops in Philip Glass’s Glassworks are programmed to be broken by loop breakers, while the motivic loops are designed as loops within loops with the interchanges of intervalic qualities.

Sheet Music download.

Façades (V)

Rubric (Glassworks) sheet music

Floe (Glassworks) sheet music

In The Upper Room #5 (Glassworks) sheet music

In The Upper Room #6 (Glassworks) sheet music

Browse in the Library:

Or browse in the categories menus & download the Library Catalog PDF: