Robert Fripp, the amazing guitarist (4): KING CRIMSON and Brian Eno

Browse in the Library:

Or browse in the categories menus & download the Library Catalog PDF:

Robert Fripp, the amazing guitarist (4): KING CRIMSON and Brian Eno

The Formation of King Crimson III

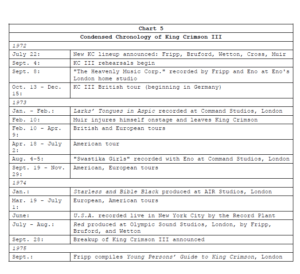

King Crimson II disbanded after the “Earthbound” tour, whose last gig was in Birmingham, Alabama, on April 1, 1972. Fripp was looking for something new. In November he was to say of the Earthbound period, “Having discovered what everybody [in the band] wanted to do, I found I didn’t want to do it.” (YPG 21, quoting from Sounds, Nov. 4 1972) On the following page is a condensed chronology of activities taking us from this point to the end of the King Crimson III period.

References to the printed booklet included in The Young Persons’ Guide to King Crimson are herein indicated by the abbreviation YPG followed by column numbers. The booklet itself, however, contains neither page nor column numbers. Therefore, if you wish to find the exact location of a YPG quotation listed in these Notes, you must number the columns in YPG yourself. Begin with “1” at the first column (1968-June 1).

Immediately following the Earthbound tour, in May 1972, Fripp set about forming a new King Crimson. This time, you can practically hear the man muttering under his breath, it’s no more Mr. Nice Guy. In point of fact, Fripp was determined to make a break from the chaos and instability of KC II as well as from some of the musical styles of that “interim” period, to get back somehow to the intangible spirit of King Crimson that was continuing to haunt him like a demon. Perhaps as a symbol of the changes to be made, Fripp cut his long frizzy hair around this time and sprouted a neat little beard – changing his visual appearance from latter-day hippie to fastidiously groomed young intellectual musician.

A man like Fripp does not believe that things happen by accident, but rather looks for synchronistically significant signs, reading the screen of his perceptions as a metaphorical psychic tableau. In the late spring of 1972 a number of such signs seemed to present themselves in an auspicious constellation, and Fripp’s confidence was high.

To begin with, there was the matter of enlisting the talents of experimental percussionist and notorious mystical crazy man Jamie Muir, whose list of avant-garde credits included work with saxophonist Evan Parker, guitarist Derek Bailey, the Battered Ornaments and Boris. Muir’s name had been crossing the screen of Fripp’s awareness for several years. Fripp had felt it inevitable that some day they would work together. He told an interviewer in 1973, “When I finally phoned him up, we talked as if we’d known each other for a long time. He expected to be in King Crimson and had been waiting for my call.” (Crowe 1973, 22)

Then there was the matter of bassist/singer John Wetton, who, like Muir, had been on Fripp’s mind for some time. Wetton was, like Fripp, Greg Lake, and several other musicians in the King Crimson circle, from the Bournemouth area – Fripp and Wetton had known each other in college – and had worked his way up in local bands before joining the eclectic progressive rock group Family in 1970. Wetton left Family to briefly join Mogul Thrash, and when that band fell apart in early 1971, Wetton, looking for work, called Fripp up in late January, a week after Fripp had concluded his torturous and lengthy auditioning of bass players by choosing Boz. By October 1971, Fripp had a proposition for King Crimson II members Collins, Boz, and Wallace, as well as for Wetton: Wetton would join the band, freeing Boz to concentrate more on his vocal duties. The band members rejected the idea; they wanted Boz to continue on bass.

For his part, Wetton declined; he later said, “I didn’t think I’d get on with that band at all. Fripp was just using me then as an ally. Saying ‘Listen, I’m outnumbered; there are three people who want to play this kind of music and only me who wants to play this kind of music. Help.’ I didn’t think that was a very good pretext for joining the band so I said no.” (Rosen 1983, 22) Score one for Wetton’s strength and independence; so far so bad for Fripp’s designs on Wetton’s talents. But when KC II finally came apart, the time was ripe: what had been out of sync now fell together, and Fripp and Wetton finally seemed to need each other at the same time.

Wetton later said the idea was to rebuild the band from the ground up: “We totally re-designed the band, we updated it. I felt that the band before ours, the Islands band, was a little dated. They were trying to play pseudo kind of pop funk and it just didn’t gel. So we put it back on the rails again and headed it in a progressive direction with Larks’ Tongues in Aspic.” (Rosen 1983, 22) Wetton, who after KC III was to play with Uriah Heep and Asia, had a vigorous, muscular touch with the bass and was known for his habit of breaking strings.

Then there was the business of Yes drummer Bill Bruford, who had also been filtering in and out of Fripp’s line of vision ever since March 1970, when Yes had asked Fripp to join the band to replace guitarist Peter Banks. Fripp had declined, intent on pursuing his musical goals within the framework of King Crimson (even though King Crimson at that point in time was rather in disarray). From then to the spring of 1972, Yes went on to do what many, feel was their best work, culminating in the epic rock sonata “Close to the Edge.” Around May or June 1972, Fripp, guitar and amplifier in tow, joined Bruford for dinner at the latter’s house one evening. After the repast they played a bit of music together at Fripp’s suggestion, and before you could say “incredible drummer – obvious choice,” Bruford had accepted a post in King Crimson.

Thus was born a musical collaboration which in a sense endured for over a decade, since Bruford was back when King Crimson was born again, mark IV, in the 1980s. Perhaps more than most of the musicians who have played in King Crimson, Bruford bought into the Frippian philosophy ever hovering somewhere amid the shadowy columns of the Court – a philosophy for which Fripp, of course, refused to take direct credit (or in a sense responsibility), preferring to reserve that honor for the mythical entity of “King Crimson” itself.

When KC IV broke out in 1981, for instance, Bruford, simultaneously endorsing and distancing himself from the philosophy, would say that despite the endless personnel changes over the years, “basically this thing, King Crimson, continues, because there was a spirit about it and an attractive way of thinking about music, some ground rules, which continue. Robert will talk endlessly about icons and things, but to us plain Englishmen it just seems a very good idea for a group and we’ve re-harnessed this, we’ve kind of gone back into it.” (Dallas 1981, 27)

There were those in the music press who wondered aloud why Bruford would choose to quit Yes, a group that precisely then was sitting on top of the pinnacle of commercial and artistic success, to join King Crimson, a somewhat suspect band, not quite on the same rank from a sales viewpoint – a band which had by this time become almost a joke in terms of its perpetual instability and volatility, and whose music was perceived as uneven, risky, and of dubious commercial value.

But for his part, Bruford felt he had learned all he could musically from the Yes lineup; an artistic adventure with Fripp and company held out potentially greater personal rewards than continuing to beat time for one of progressive rock’s unquestioned supergroups. He was also eager to work with percussionist Muir, who appeared to Bruford as a direct link with “the world of free jazz and inspiration,” as he put it. (Crowe 1973, 22)

Fripp, as part of his overall effort to banish immediate musical memories and habits, to rejuvenate his imagination, decided against using a reed player, saxophone had been a big part of the whole King Crimson sound right from the beginning, one reason why the group was so strongly associated with jazz-rock. Fripp instead opted for a violin and viola player who could complement his own melodic guitar work with a new range of tone color, and who could also double on mellotron and other keyboards in certain situations.

That player was David Cross, a musician with a classical background who had floated around the music scene and had worked with a pop-rock singer named P.J. Proby and folk-rock band the Ring. Cross described his recruitment casually: “Yeah, Robert came down and we got it together and had a couple of blows.” (Corbett 1973, n.p.) Like Bruford, Cross found the prospect, and then the reality, of working with percussionist Muir exciting; in 1973, he was to say, “We all learned an incredible amount from Jamie. He really was a catalyst of this band in the beginning and he opened up new areas for Bill to look into as well as affecting the rest of us.” (Corbett 1973, n.p.)

By July 1972 King Crimson III – Fripp, Muir, Wetton, Bruford, and Cross – was complete. Rehearsals commenced on September 4. The following year, Fripp would tell Rolling Stone writer Cameron Crowe: “I’m not really interested in music; music is just a means of creating a magical state … One employs magic every day. Every thought is a magical act. You don’t sit down and work spells and all that hokey stuff. It’s simply experimentation with different states of consciousness and mind control.” (Crowe 1973, 22) This from a man who had made (and to this day still makes) a deliberate practice, even a personal crusade, of not using drugs – from a musician some have perceived as the world’s most rational rock star.

Robert Fripp viewed King Crimson as something outside himself, an entity, a being, a presence, which he could respond to, whose instrument he could become, but which was somehow intrinsically beyond him, not of his own creation, and over which, in spite of his dogged efforts to serve, he could ultimately exercise no real control. Fripp could say King Crimson was “too important to let die,” and devote the better part of his life energy to keeping it alive, but in the final analysis he acknowledged it had a life and will of its own.

Struggling mightily with this force, a force perceived to be other, outside the realm of the personal ego, making journeys into the realm of the magical, the unknown, the unconscious, Fripp repeatedly persevered and brought back fragments of the world lying below or beyond everyday awareness. King Crimson, a name coined to stand for Beelzebub, the devil, prince of demons, was a power that Fripp felt called to contend with.

Fripp was, in the latter half of the 1980s, to formulate and officially promulgate the image of a more benevolent presence to whose call he had responded: he would call it simply “music.” But in mid-1972, music’s alter ego, or shadow, or compellingly seductive twin, or bastard offspring, or fallen angel, still commanded the twenty-six-year-old Fripp’s imagination: he called it “King Crimson.”

Fripp and Eno

Throughout his tenure with King Crimson in the 1970s, Fripp found time to do session work with other musicians. He guested on Van der Graaf Generator’s H to He Who Am the Only One (1970) and Pawn Hearts (1971), as well as on Peter Hammill’s solo 1972 album Fool’s Mate. As a producer, Fripp’s credits included Centipede’s Septober Energy (1971), Matching Mole’s Little Red Record (1972), and Keith Tippett’s Blueprint (1971) and Ovary Lodge (1972). Fripp met many musicians in his travels; one planned collaboration that didn’t pan out was to have been an album with former Procol Harum guitarist Robin Trower, a project Fripp mentioned in a 1974 interview. (Dove 1974, 14)

One evening in September 1972, around the same time as KC III was commencing rehearsals, Brian Eno invited Fripp over to his home studio and showed him a system of producing music by using two tape recorders set up so that when a single sound was played, it was heard several seconds later at a lower volume level, then again several seconds later at a still lower level, and so on. The system permitted adjustments of various kinds, having to do with volume levels and length of delay; further, the live signal could be disconnected from the loop, so that the already-recorded sounds would repeat indefinitely while a live “solo” line could be played over the top. With this simple set-up, the two musicians set gleefully to work, and within forty-five minutes had produced a long (20’53”) piece they called “The Heavenly Music Corporation,” which was to become Side One of their No Pussyfooting album, released the following year.

Fripp had the highest respect for Eno, in spite of the fact that the latter’s instrumental skills were minimal. Fripp said in 1979, “Eno is one of the very few musicians I’ve worked with who actually listens to what he’s doing. He’s my favorite synthesizer player because instead of using his fingers he uses his ears.” (Garbarini 1979, 32)

With its drony opening, its rhapsodic modal guitar melodizing, its hypnotically returning cycles of phrases, and its sheer duration, “The Heavenly Music Corporation” could be called a

classic mixture of raga, minimalism, and rock, were it not for the fact that Fripp wasn’t using Indian scales in any systematic way, nor had he yet had much exposure to the American minimalists. A guitarist’s and technician’s tour de force, the piece rewards close listening with its slow changes of color, emphasis, and tonality. For once, Fripp did shut out all distractions, remove all superfluous musical elements, and just play his guitar.

No Pussyfooting was a major point of departure for both musicians, and Fripp seemed to recognize it instantly as such. So much did Fripp like “The Heavenly Music Corporation” that when King Crimson went on the road in the fall of 1972, he would play the tape before the band came onstage and after they left. Fripp and Eno would continue to collaborate throughout the 1970s: 1975 saw the release of their joint ambient album Evening Star, Fripp’s first major release following the demise of King Crimson III, and Fripp guested on Eno’s solo albums Here Come the Warm Jets (1973), Another Green World (1975), Before and After Science (1977), and Music for Films (1978). A number of brilliantly inspired Fripp guitar solos are stashed away in these albums, notably on the songs “Baby’s On Fire” (Here Come the Warm Jets) and “St Elmo’s Fire” (Another Green World).

The “Larks’ Tongues” Period

With scarcely a month of rehearsals behind them, King Crimson III played four gigs in October at Frankfurt’s Zoom Club, followed by one at the Redcar Jazz Club. Between November 10 and December 15 they toured Britain, playing twenty-seven gigs. There was a renewed emphasis on improvisation in live performance in King Crimson’s music of this period – but not the kind of improvisation common in jazz and rock, where one soloist at a time takes center stage and riffs and rhapsodizes, running through his chops while the rest of the band lays back and comps along with set rhythm and chord changes.

In its best moments, King Crimson improvisation during this period was a group affair, a kind of music-making process in which every member of the band was capable of making creative contributions at every moment. Mindless individual soloing was frowned upon; rather, everyone had to be listening to everyone else at every moment, to be able to react intelligently and creatively to the group sound. This was a period when Fripp stressed the “magic” metaphor time and again; for to him, when group improvisation of this sort really clicked, it was nothing short of bona fide white magic.

Violinist/keyboardist David Cross described the process this way:

“We’re so different from each other that one night someone in the band will play something that the rest of us have never heard before and you just have to listen for a second. Then you react to his statement, usually in a different way than they would expect. It’s the improvisation that makes the group amazing for me. You know, taking chances. There is no format really in which we fall into. We discover things while improvising and if they’re really basically good ideas we try and work them in as new numbers, all the while keeping the improvisation thing alive and continually expanding.” (Corbett 1973) Bruford stressed the group participation in improvisation, using the image of “a kind of fantastic musical sparring match.” (YPG 22, Sounds, Nov. 18 1972)

Other than in the memories of those who went to King Crimson concerts in the Larks’ Tongues period, in the published reviews, and in bootleg tapes of the music, there is no record of what was by most accounts a musical phenomenon that had to be experienced to be believed. Bill Bruford, for one, was surprised by the positive reaction to the group’s playing: “After all, we walk on stage and play an hour and a quarter of music which isn’t on record, and they haven’t heard before, often with no tonal or rhythmic centre.” (YPG 23, MM, Dec. 2 1972)

Following the first KC III British tour (which concluded on December 15), in January and February of 1973 King Crimson went into Command Studios in London to make the album that would become known as Larks’ Tongues in Aspic. It was Muir who came up with the title. When the group was playing back a tape of an instrumental piece they had just made, Muir was asked what it reminded him of; he said without hesitation, “Why, larks’ tongues in aspic, what else?” (Crowe 1973, 22) (Aspic is defined as a jelly used to garnish or make a mold of meat or vegetables, or a lavender yielding a volatile oil. Take your pick.) The degree to which the music of Larks’ Tongues reflects King Crimson’s live playing of the period is open to debate, yet it seems that the two collectively-composed instrumental pieces, “Larks’ Tongues in Aspic, Part One,” and “The Talking Drum,” contain, even in their studio versions, significant elements of group improvisation.

The other instrumental, “Larks’ Tongues in Aspic, Part Two,” is listed as a Fripp composition, and the remaining three pieces are more or less carefully worked-out songs with lyrics by Richard Palmer-James. However well Larks’ Tongues represents or does not represent the live Crimson sound, though, at least the album was made in what Fripp considered to be the proper organic sequence: first you go out and make live music and get the audience’s feedback, then you go into a studio to record the music you have created in a live situation – rather than first composing and recording an album in sterile conditions and then going on the road to “promote” it.

Furthermore, with Larks’ Tongues King Crimson was decisively back in a situation of collective authorship; the music of the previous two studio albums, Islands and Lizard, had been entirely by Fripp (even the composition of Poseidon had been mostly Fripp’s affair). Cross put it this way: “We all did contribute equally to the ‘Larks’ Tongues in Aspic’ album, although Robert was definitely the unifying force behind it.” (Corbett 1973, n.p.) The album’s cover sported a symbolic tantric design of the moon and sun embedded in each other – a union of masculine and feminine principles.

LARKS’ TONGUES IN ASPIC

• David Cross: violin, viola, mellotron

• Robert Fripp: guitar, mellotron and devices

• John Wetton: bass and vocals

• Bill Bruford: drums

• Jamie Muir: percussion and allsorts

Side One

LARKS’ TONGUES IN ASPIC, PART ONE (by Cross, Fripp, Wetton, Bruford, and Muir). Opens with Muir rapidly stroking a thumb piano. Bells/cymbals and a high flute enter. Crescendo of cymbal trill, descrescendo of thumb piano. Repeated notes on violin; fuzz guitar careens through diminished harmonic areas; Bruford warms up on drums, then whole band slams in. Shall I go on? In essence, what follows is an impressive and somewhat scarifying display of group togetherness, in a number of sections set off by contrasting instrumentation, textures, harmonic premises, dynamics, and mood. Conflict and contrast continue to be dominant issues in King Crimson music, in this piece there is everything from solo fiddle to crashing fusion band and quasi-oriental unison lines. (I don’t believe it – I just played the whole thing at 45 RPM while writing this – daughter Lilia was playing speeded-up Switched-on Bach this morning, as is her wont. So it wasn’t just that cup of dark French roast – I thought “Larks’ Tongues, Part I” was longer than that. Actually sounded pretty good, though – the structure was more evident than I’ve ever heard it before.)

BOOK OF SATURDAY (by Fripp, Wetton, and Palmer-James). An evocative, melancholy minor ballad. Not like earlier Crimson ballads however: more energy, movement, pluck, and a few little twisty harmonic and rhythmic complications to take it out of the 4 + 4 + 4 + 4 phraseology that dragged down some earlier songs.

EXILES (by Cross, Fripp, and Palmer-James). Strange burblings and percussives lead into another moody song, sung verses alternating with freer pulseless sections. The sung bridge contains some remarkable (for rock) modulations – Wetton taking a tip or two from the Brahms/Procol Harum harmonic cookbook. One thing one notices is how Bruford is able, and here willing, to keep himself out of the way more than previous KC drummers – more the Ringo Starr school of percussion, which in a song like “Exiles” is entirely appropriate.

Side Two

EASY MONEY (by Fripp, Wetton, and Palmer-James). Funny thing, having the accompaniment in 4 and the vocal in 7. Makes you feel like there’s a fifth wheel on the cart somewhere. But clearly, metrical complications do not in themselves music make. In spite of valiant “funny sounds” efforts by Muir, the long instrumental portions never really take off.

THE TALKING DRUM (by Cross, Fripp, Wetton, Bruford, and Muir). Sound effects move to tritone bass ostinato over softly percolating percussion and drums, Cross and Fripp come in with modal soloing (and a funny mode indeed it be) tonic of A, scale A-Bb-C-C#-D#-E-F-G#, with other notes from time to time), gradual crescendo, suddenly broken off molto appassionato by horrific squeals, which launch directly into …

LARKS’ TONGUES IN ASPIC, PART TWO (by Fripp). On the one hand, an intellectual metrical exercise (O.K. fellows, can you count this?) and an arcane study in whole-tone, tritone, and other exotic chord root relationships, and on the other hand a stingingly original and strangely rousing piece of instrumental rock and roll. Yeah, you can say that the rhythmic organization is “studied,” “labored,” “unnatural,” and so forth. But for Fripp music like this offers the opportunity for players and audiences to concentrate, to concentrate in that peculiar way only difficult music can make us. Try playing it at 45 (turning up the bass to compensate for lost low frequencies) – I just did (intentionally this time), and it sounds much more “musical.”

Dynamic contrast is of the essence in the music of Larks’ Tongues. There is a psychological difference between loud and soft, after all, and in an age when compressors and limiters have squashed the dynamic range of recorded popular music down to the point where a delicately plucked acoustic guitar note or sensitively crooned vocal phrase comes out of your speakers at the same actual volume level as the whole damned synthesized band when it’s blowing away at top intensity, listening to Larks’ Tongues’ startling contrasts of dynamics is a tonic for the ears. It’s more real, it’s more true. Y’know what I mean?

The “Starless” Period

King Crimson played two gigs at London’s Marquee on February 10 and 11, 1973 – dates booked, according to Bruford, for “pure enjoyment and relaxation” to take some pressure off the band during the period of the intense Larks’ Tongues recording sessions. (Crowe 1973, 22) At the first gig, Muir dropped a gong on his foot, causing an injury of sufficient seriousness to prevent him from playing the following night. Bruford, who viewed Muir’s presence as fundamental to King Crimson, assumed that they would have to cancel the gig, but the other members convinced him that they should carry on as a quartet. (Although Muir occasionally sat down behind a trap set to augment Bruford’s drumming, his primary role seems to have been to provide dynamism with his animated stage presence and to gloss the music with an assortment of unusual sounds from a wide variety of percussion instruments, chimes, bells, mbiras, a musical saw, shakers, rattles, and miscellaneous drums.)

King Crimson, minus Muir, went ahead and did the Marquee date, and shortly thereafter Muir left the group permanently, to pursue other – shall we say perhaps related – interests: he became a monk in a monastery in Scotland.

When the recording of Larks’ Tongues was finished, King Crimson – Fripp, Bruford, Wetton, and Cross – embarked on an extensive series of tours: Britain (nine gigs, March 16 – 25); Europe (nine gigs, March 30 – April 9); America (forty-four gigs, April 18 – July 2). Back in London, Fripp took time out from King Crimson to record “Swastika Girls” (Side Two of No Pussyfooting) with Eno at Command Studios on August 4 and 5. King Crimson rehearsals in August laid the foundations of four new pieces, “Lament,” “The Night Watch,” “The Great Deceiver,” and “Fracture,” all of which were to appear on the 1974 album Starless and Bible Black.

Soon Crimson was back on the road again, with tours of America (nineteen gigs, September 19 – October 15), Britain (six gigs, October 23 – 29), and Europe (eighteen gigs, November 2 – 29). The live band continued to astound audiences and critics with their virtuosity, the scope and power of their music, and their unique outlook.

Fripp, King Crimson’s acknowledged leader, puzzled many and delightedothers with his inscrutable attitude and onstage banter. He reportedly told a Milwaukee audience on September 28, “We’re not to be enjoyed – we’re an intellectual band.” (Commenting on this remark and the sarcastic reaction it elicited from a Milwaukee critic, Fripp wrote in the Young Persons’ Guide to King Crimson, “We were surprised that so many people took everything we did so seriously.”) (YPG 27-28, Milwaukee Sentinel, Sept. 29 1973) The funny thing about Fripp, though, was that he could be so funny when he was on and when the audience was tuned into his peculiarly pontifical sense of humor. At the April 28 concert at New York’s Academy of Music, for instance, a Variety writer reported that Fripp delivered “a short comic rap plugging their new album” (Larks’ Tongues) that was “uproarious.” (Kirb 1973A, 245) When King Crimson returned to the Academy of Music on September 22, things weren’t so jolly: a breakdown in their complicated sound system caused a delay of more than two hours as a new system was hastily procured and set up. (Kirb 1973B, 272)

The exhaustion of touring, the technical problems, the surreal conditions of road life, the ever-questionable band-audience relationship, and the problematic nature of making music under such circumstances were beginning to take their toll on Fripp.

It was a pair of gigs at Italian sports arenas on November 12 and 13 that he was later to call the “turning point” for him in terms of his ability to “put up with the nonsense” that goes along with putting on a rock show. In one of his 1981 articles for Musician, Player, and Listener Fripp described the Felliniesque insanity that surrounded those two days in Turin and Rome: Maoists protesting for free admittance to the first show and crashing through a glass wall; Cross and Bruford getting drunk at an expensive dinner, throwing open wine bottles through the air and insulting the promoter’s homosexual partner; concert ticket collectors stuffing their own pockets with cash receipts; backstage machine-gun-toting security police; a stoned hippie who in full view of the audience was beat bloody by the promoter’s gun-carrying right-hand man for wandering onstage; and a desperate attempt at an encore almost scotched because members of the audience had pulled out the power cables. Fripp’s account of the whole fiasco is a miniature classic of rock tragicomedy, but the moral here is that the Italian gigs were the real beginning of the end for King Crimson.

As Fripp concludes his story, “A few months later King Crimson ‘ceased to exist’ and I began to talk a lot about small, mobile and intelligent units.” (Fripp 1981B, 48)

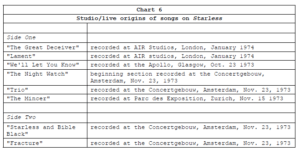

The frantic tours of 1973 concluded, King Crimson retired to London’s AIR Studios in January 1974 to produce their next album, Starless and Bible Black. (The title is a phrase borrowed from Dylan Thomas. By way of injecting some levity into a band situation that tended toward gravity, Bruford was fond of renaming Crimson albums; this one he called “Braless and Slightly Slack.”) (DeCurtis 1984, 22) Although edited and mixed in the studio, all but the first two pieces on Starless were recorded live at King Crimson gigs in the fall of 1973. The essentially live nature of Starless received little if any attention in the press, who treated it as a studio album; the recording quality is superb, and all audience noise save a stray distant shout here and there has been skillfully deleted. Perhaps no one knew this was a live album until Fripp spilled the beans in the fine print of the Young Persons’ Guide.

Starless was the first King Crimson album other than the live Earthbound not to provide the lyrics on the cover or inner sleeve – perhaps intentionally to de-emphasize the verbal content?

STARLESS AND BIBLE BLACK

• David Cross: violin, viola, keyboards

• Robert Fripp: guitar, mellotron, devices

• John Wetton: bass and voice

• William Bruford: percussives

THE GREAT DECEIVER (by Wetton, Fripp, and Palmer-James). Studio recording. Slams off with a bluesy riff at hyperspeed. Sectional song contrasting instrumentals and vocals. Oblique references to the Devil. “The Great Deceiver” contains the only lyrics ever penned by Fripp for a King Crimson song: “Cigarettes, ice cream, figurines of the Virgin Mary” – a comment, he explained in 1980, on the woeful commercialization of Vatican City, which he’d visited on a Crimson tour in 1973. (Watts 1980, 22)

Reminding now a passage from the autobiography of spiritual teacher J.G. Bennett, who was to become a major influence on Fripp in 1974: “I can see how necessary it is to establish a new understanding of the Incarnation. The Church is equally astray in its conservative and in its modernist wings, nor is the center any better. The Catholic Church is the custodian of a mystery that it does not understand; but the sacraments and their operation are no less real for that.” (Bennett, Witness, p. 354)

LAMENT (by Fripp, Wetton, and Palmer-James). Studio recording. Slow Beatlish ballad that breaks out into rather more manic territory as the song progresses … a la Lennon in the White Album period. The Beatles never had a coda that jammed out for a few bars in seven, however.

WE’LL LET YOU KNOW (by Cross, Fripp, Wetton, and Bruford). Live recording. Instrumental. Gradually coalesces, as so many King Crimson pieces do, out of sensitively random, intentionally chaotic points of noise, into motives, rhythms, melodies: into music … of a sort.

THE NIGHT WATCH (by Fripp, Wetton, and Palmer-James). Introduction/beginning, live recording. Deftly spliced to the studio-recorded body of the song. Classic King Crimson minor ballad. Effectively understated ending.

TRIO (by Cross, Fripp, Wetton, and Bruford). Live recording. Peaceful, contemplative, tonal, somewhat out of character for a King Crimson III improvisation. Although Bruford does not play on “Trio,” he is listed as one of the co-composers. Fripp later wrote in admiration of his drummer’s restraint in this instance, explaining that Bruford was awarded joint authorship on the basis of his having “contributed silence.” (Fripp 1981B) The same role – the conscious embodiment of the presence of silence – would later occasionally be assigned to a particular member of the League of Crafty Guitarists in their live performances.

THE MINCER (by Cross, Fripp, Wetton, Bruford, and Palmer-James). Live recording, with a few overdubs. Another example of what Crimson III was liable to sound like in the throes of improvisation. The song ends unaccountably in the middle – it sounds like the tape ran out.

Side Two

STARLESS AND BIBLE BLACK (by Cross, Fripp, Wetton, and Bruford). Live recording. More gradual coalescence out of chaos. The piece recalls the first chapter of the Book of Genesis, “And the earth was without form, and void; and darkness was upon the face of the deep. And the Spirit of God moved upon the face of the waters.” A lot of the high melodic stuff you hear is not Fripp but David Cross cranking up the distortion on his electric violin. Fripp ruminates meanwhile on his mellotron. Tonal center?

Pieces like this can sound totally improvised until, miraculously, everyone slams into a downbeat at precisely the same moment. You never know with King Crimson. As Bruford said, “What we’re really trying to do is to abolish the distinction between formal writing and improvising. Some of our most formal passages sound improvised and vice versa.” (Rosen 1983, 23)

FRACTURE (by Fripp). Live recording. Fripp lays down a typically edgy angular ostinato. There’s a lot of whole-tone-scale action going on in here. One of the most extensively worked-out pieces of the KC III period, “Fracture” places severe demands on technique. “One of the reasons I wrote ‘Fracture’ in the manner which I wrote it,” said Fripp, “was to put myself (and the band) in a certain situation where I had to practice every day because it’s so difficult.” (Rosen 1983, 23)

The “Red” Period and the Dissolution of King Crimson III

Inspiration continued to pay calls from time to time, but improvisation in the latter stages of King Crimson III grew increasingly frustrating. In February 1974, for instance, David Cross was reportedly having reservations: “It sometimes worries me, what we do – we stretch so far and our music is often a frightening expression of certain aspects of the world and people. It is important to have songs as well, written material, to counter-balance that so that they’re not actually driven insane … We’ve only had one moment of true peace in improvisation with this band, which was a thing we did with just violin, bass and guitar at a concert in Amsterdam. Most of the time our improvisation comes out of horror and panic.” (YPG 29, Sounds, Feb. 9 1974) (The “moment of peace” Cross refers to is probably “Trio” as heard on Starless; he got mixed up as to the instrumentation, which is actually violin, flute-mellotron, and guitar.)

In an interview published in May, Fripp went public with his own reservations. The group was still trying out improvisational formats in live situations, Fripp explained: “What we do live is maybe just say, ‘Bill, you just start playing, and we’ll follow you.’ But since this band isn’t very sensitive or interested in listening to everyone playing, the improvisation in the band at the moment is extremely limited and more concerned with individuals showing off than in developing any kind of community improvisation … I find it most frustrating that I can’t make the other players in the band take as much interest in my playing as I do in theirs.” (Rosen 1974, 35) With what was, from his perspective, one of King Crimson’s primary raisons d’être having stalled, it is not surprising that Fripp was beginning to lose interest in keeping the band alive. But there were other reasons too, as we shall shortly see.

Although not even Fripp was fully aware of the fact, King Crimson III after the Starless studio sessions in January 1974 was on its last legs. The band undertook three more road trips: Europe (eleven gigs, March 19-April 2); America (seventeen gigs, April 11-May 5); and a final U.S. tour (twenty-one gigs, June 4-July 1). The live album USA, released around April 1975, was recorded toward the end of this final U.S. tour: the song “Asbury Park” at the Asbury Park (New Jersey) Casino on June 28, and the rest two days later at the Palace Theatre in Providence, Rhode Island.

USA

• David Cross: violin and keyboards

• Robert Fripp: guitar and mellotron

• John Wetton: bass and voice

• William Bruford: percussives

USA clearly shows that in terms of sound, at any rate, there was little or no difference between live and studio King Crimson of this period: as the band runs through “Larks’ Tongues in Aspic, Part II,” “Lament,” “Exiles,” and “Easy Money,” there are few discernible musical differences between these and the previously recorded studio versions. Very slightly choppy around certain edges, less dynamic range, not quite so beautifully recorded as the studio tracks, USA nevertheless demonstrates that very late KC III was eminently capable of delivering the goods live.

The one new track, “Asbury Park,” represents King Crimson improvising straight ahead in 4/4 with Fripp and Cross getting in some vintage licks over Wetton’s razor-sharp melodic bass lines and Bruford’s crisp drumming – but one does sense a certain lack of group consciousness: for long sections it’s four individual virtuoso musicians, each blowing his own horn.

The crowd’s rowdy shouting through the soft introduction to “Exiles” gives some indication of one predicament Fripp was finding himself in, namely, how to break their expectations down sufficiently to get them to shut up and listen.

USA closes with a rendition of “Schizoid Man.” Since the album was actually released after “Red,” one has the feeling that Fripp was seeking something of a framing effect for King Crimson’s total recorded output, which had begun six years earlier with the same song. In small print at the bottom of USA’s back cover are the letters: “R.I.P.”

King Crimson life was indeed finished with the “USA” tour, but no one recognized it at the time, not even Fripp, who said of the final gig, in New York’s Central Park on July 1 1974, “For me it was the most powerful since 1969.” (YPG 30, July 1) A week later the band – minus David Cross – was back in a London studio, at work on the album that was to become Red. Red would not be released, however, until after Robert Fripp had unilaterally disbanded King Crimson and talked to the press, offering three reasons why the King had to die: “The first is that it represents a change in the world. Second, whereas I once considered being part of a band like Crimson to be the best liberal education a young man could receive, I now know that isn’t so. And third, the energies involved in the particular lifestyle of the band and in the music are no longer of value to the way I live.” (YPG 31, MM, Oct. 5 1974)

At the cosmic level – the level of the changing world situation – Fripp spoke of a radical transition from the old world to the new. The old world was characterized by “dinosaur” institutions, social organizations, corporations, rock bands – as Fripp put it, “large and unwieldy, without much intelligence.” (Ibid.) Looking to the future, Fripp foresaw “a decade of considerable panic in the 1990s – collapse on a colossal scale. The wind-down has already started … It’s no doomy thing – for the new world to flourish the old has to die. But the depression era of the Thirties will look like a Sunday outing compared to this apocalypse. I shall be blowing a bugle loudly from the sidelines.” (Dove 1974, 14)

On the level of the music industry, Fripp had developed grave reservations: a dinosaur itself, “the rock & roll business is constructed on wholly false values, impermanent and mainly pernicious, although not in an obvious way.” (Dove 1974, 14) Later, toward the end of the 1970s, Fripp would develop a systematic critique of music industry practices, write it up, and publish it in Musician, Player, and Listener magazine. For now he simply knew that he had had enough, and was looking to a future of “small, independent, mobile and intelligent units” to replace the lumbering Mesozoic automaton behemoths that passed for rock acts in 1974. (SMALL, INDEPENDENT, MOBILE, AND INTELLIGENT UNIT became the Frippism par excellence of the late 1970s and early 1980s. Its first appearance in print is apparently YPG 31, MM, Oct. 5 1974.)

On the level of the role he himself was playing in the rock and roll circus, Fripp had long felt frustration. At gigs like the ones in Italy already discussed, for instance, in which, as Fripp put it, “the performance itself went quite well,” King Crimson’s artistic method had itself become brutal: “We battered the crowd with sound for forty minutes to make enough room for ten minutes of experimenting. Then, as attention wandered, we built up another level of pounding for twenty or thirty minutes, so a pulped crowd would feel it had its money’s value and go home happy.” (Fripp 1981B, 114)

Elsewhere Fripp spoke with despair of his perception that the marijuana and LSD of the sixties had been gradually replaced by the cocaine, speed, and alcohol of the seventies, and that along with that shift went a corresponding change in audience demeanor.

This is art? This is magic? This is music? Beating the audience back, an audience either in a blind stupor or artificially stimulated, fighting the collective aggression of five thousand people, having to use your own limited energy to do it, night after night – this was accomplished, as Fripp expressed it, only “at the expense of creating something of a higher nature.” (YPG 31, MM, Oct. 5 1974)

At the personal level, there was the matter of continuing his own “education”, as he later described his predicament, he felt he had to disband King Crimson “because I could not see how it was possible to be a musician and a human being simultaneously.” (Kozak 1981, 10)

But there was a deeper, and perhaps decisive reason why King Crimson had to be put to rest – an overwhelmingly powerful personal experience which so far as I know Fripp did not venture to disclose publicly until some five years after the fact, probably because it took him that long to understand what had actually happened. When he did talk to Melody Maker writer Allan Jones about it in 1979, he said that in the interviews done immediately following the Crimson break-up, he hadn’t known how to explain it.

I had a glimpse of something… The top of my head blew off. That’s the easiest way of describing it. And for a period of three to six months it was impossible for me to function … My ego went. I lost my ego for three months. We were recording “Red” and Bill Bruford would say, “Bob, what do you think?” And I’d say, “Well-” and inside I’d be thinking, how can I know anything? Who am I to express an opinion? And I’d say, “Whatever you think, Bill. Yes, whatever you like.”… It took me three to six months before a particular kind of Fripp personality grew back to the degree that I could participate in the normal day-to-day business of hustling … (Jones 1979A, 19)

Given the pressure-cooker atmosphere into which commitment to the ever intangible yet fervently embraced idea of King Crimson had plunged him for five years – the surging and dashed hopes, the sensitive perception of false values all around, the perpetual instability of the band, the press filled with acclamation and denigration by turns, the uncertainties about his own accomplishments, aims/ends, and means of attaining them – it would perhaps not be difficult to explain away Fripp’s loss of ego in banal psychological terms. But to do so would be to miss and trivialize the fundamental point, which is that Fripp, to put it simply, had a revelation.

The proverbial straw was reading the text of a lecture by J.G. Bennett the night before the Red recording sessions were to begin; the “Second Inaugural Address” to Bennett’s International Academy for Continuous Education in Sherborne. The Text was printed in the appendix to Bennett’s book Is There Life on Earth? This was the first time Fripp had come into contact with the teaching of Bennett, who had been a disciple of the infamous George Gurdjieff and had met many of the twentieth century’s leading mystical seekers. (REPORTEDLY THE FIRST TIME Schruers 1979, 16) Bennett and Gurdjieff taught that people ordinarily go through their lives in a state of relative unconsciousness; some of the methods Bennett and Gurdjieff used to “wake up” their students will be discussed in the next chapter. Fripp’s first encounter with Bennett’s ideas was electrifying, precipitating a major change of direction in his life.

Wetton and Bruford were both to express regrets with regard to Fripp’s unilateral decision to break up the band. Bruford, who had quit the highly successful Yes to join King Crimson, and who had viewed Crimson as a unique opportunity to expand his horizons as a musician, did his best to be philosophical: while pointing out that Crimson’s enviable position in the music world was the result of years of hard work by musicians, management, and devoted road crew, and that to have all that dashed at a stroke was “mildly irritating,” Bruford said nevertheless he could cope with his irritation since it ultimately represented a “false adherence to [materialistic] things.” (YPG 32, Sounds, Oct. 12 1974) Below his stoic surface, however, Bruford was profoundly disappointed.

By his own estimation, Wetton had not made the kind of commitment to King Crimson that Bruford had, and had not had to give up so much to join the group. But in retrospect, he admitted being “pretty pissed when it broke up. I didn’t admit it at the time … Robert called up and explained why he couldn’t go on in the manner that we had been. He felt the world was going to come to an end and he wanted to prepare for it. And I said, ‘Yeah, sure, OK, but let’s get a good tour in first.’” (Rosen 1983, 23) (There had been, in fact, plans for another King Crimson tour, with founding King Crimson member Ian McDonald back in the band. Rehearsals had already begun when Fripp pulled the plug.)

RED

• Robert Fripp: guitar and mellotron

• John Wetton: bass and voice

• William Bruford: percussives

With thanks to:

• David Cross: violin

• Mel Collins: soprano saxophone

• Ian McDonald: alto saxophone

• Robin Miller: oboe

• Marc Charig: cornet

Backtrack to July 1974. Fripp had had the top of his head blown off, and in an ego-less state carried on, with Bill Bruford and John Wetton, with the studio production of Red. A number of previous King Crimson members (David Cross, Mel Collins, Ian McDonald) and sidemen (Robin Miller, Marc Charig) made contributions to the album. Red is a peculiarly retrospective album: glancing through the song titles (“Red,” “Fallen Angel,” “One More Red Nightmare,” “Providence,” “Starless”) one is struck as if by the facets of a diamond with the King Crimson myth/metaphor smoldering at its core.

The striking black-and-white cover photograph of Wetton, Bruford, and Fripp (first ever cover photo of band members on a King Crimson record) in lighting that casts half of their faces into shadow harks back, whether intentionally or unintentionally, to the cover of Meet the Beatles, in 1964 an image indelibly stamped into the minds of a generation. (According to Fripp, the photo of the band was Mark Fenwick’s idea; Fenwick was one of the three directors of EG Management. Fripp didn’t want the musician’s faces on the jacket; it reminded him less of Meet the Beatles than an album by Grand Funk Railroad.) On Red’s back cover is a stark photograph of a gauge with the needle pointing into the red (danger, overload) zone. Red was released in early October.

Side One

RED (by Fripp). A divinely lurching, infernally flowing instrumental that exploits Fripp’s by-now entrenched penchant for odd metrical schemes and whole-tone-scale root relationships and melodic turns. In the recurring main theme, the predominant interval between guitar (soprano) and bass is the tritone – also the sonority that ends the composition. In traditional tonal music theory, the tritone – so named because it spans three whole steps or tones, in this case the thematic example being the interval E to A# – is classed among the most dissonant of the thirteen fundamental intervals in music: if you turn in your college harmony assignment and have idiotically included a tritone in the final chord, you’ll get it back marked in red.

Because of its searingly harsh, problematic sound, the tritone was called the diabolus in musica (“the devil in music”) by medieval theorists, and some forbade its use entirely. The King Crimson metaphor – it goes deeper than one might think.

FALLEN ANGEL (by Fripp, Wetton, and Palmer-James). You think it’s going to be just a genteel McCartneyesque ballad; then the distorted guitar comes careening in, in a middle section utilizing the fifth mode of the harmonic minor scale; transition back to the ballad theme; harmonic minor fade-out.

ONE MORE RED NIGHTMARE (by Fripp and Wetton). That darned tritone outline again, those gnarly whole tones, those insane metrical changes, those fabulous fills by Bruford, hammering on a piece of sheet metal. It seems almost impossible that this was the same Fripp who had made the delicate Islands a few short years previously – a record that one of KC II’s members had reportedly called “an airy-fairy piece of shit”: this music has real muscle. (Malamut 1974, 69)

Side Two

PROVIDENCE (by Cross, Fripp, Wetton, and Bruford). This was recorded live at the Providence, Rhode Island Palace Theatre on June 30, 1974 – the gig at which most of USA was taped, the day before King Crimson III’s final performance in New York City. It begins with a delicate violin solo and goes into free-form improvisation, recalling the spaciness of “Moonchild” – but “Providence” has a ballsiness and level of aggression or even evil that “Moonchild,” in its benighted innocence, seemed to lack.

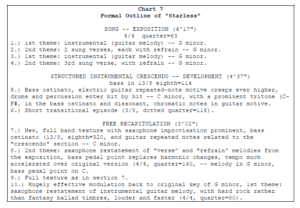

STARLESS (by Cross, Fripp, Wetton, Bruford, and Palmer-James). More retrospection, and not merely on account of the song’s title: at the outset, the mellotron’s minor tones and the stately drumming recall “Epitaph.” But “Starless” turns out to be more than just another gloomy minor mellotron epic, although clocking in at over twelve minutes it has the requisite duration. “Starless” is a grand synthesis, in one unified (if collectively authored) composition, of several of the styles Fripp and his various cohorts had cultivated since 1969: slow, melancholy minor-key epic/ballad; medium-tempo, abrasive riff-based linear counterpoint; extremely fast, frenetic group playing; and improvisational and compositional elements bound together in such a way that the seams are exceeding difficult to detect. “Starless” is more than all that, though: in my opinion it is simply the best composition King Crimson ever committed to record. It is also the only King Crimson piece that has ever made me weep – those tears that tend to issue out of a direct confrontation with what we feebly call “artistic greatness” but is really a portentous and rarely glimpsed secret locked away at the heart of human experience.

It is the curse of the scholar/writer/musician to be driven to rip apart that which he loves, dissecting and disemboweling, in a vain and perhaps pointless attempt to reduce the primal musical experience to words, formulas, theories, charts, diagrams, numbers, and so on – an exercise pleasing enough to the intellect and yet somehow painful for the heart. What follows, therefore, is not for the faint of heart, and if the reader does not give a hoot about formal musical analysis, she or he would probably do just as well to skip it. On the other hand, lest I paint myself into a corner of total futility, let me affirm my belief that at its best, analysis can be a valid form of translation – from the language of the heart into the language of the head. And inasmuch as head and heart are generally not so much in the habit of conversing amicably with each other as they could be, the translator’s enterprise is perhaps not entirely meaningless.

From listening to the music itself you can tell something about what the musicians are feeling, and open a door into that world of feeling within yourself; through analyzing the music seriously you can get some inkling of how the musicians think (and believe me, think they do, and think they must, in order to produce as coherent a piece as “Starless”), and in that process allow your intellect to go into sympathetic resonance with the intellects of those who are making the music.

Head and heart. Fripp would later develop a system of musical practice based on “hands, head, and heart,” where the “hands” represent the physical contact with the instrument and indeed with the physical world of sensation itself. We can address the head and the heart when we write a book like this, I’m not so sure about the hands, that is, about addressing the very physical presence of music in a live situation. I incline to suppose that the most we can do along those lines is to be aware of, or at least try to avoid completely losing touch with, our body as we are writing and reading.

“Starless” is a long (12’18”) sectional composition in a form that breaks down into essentially three parts; though “Starless” is not exactly a textbook example of classical sonata form, an analogy with sonata form’s three part structure (exposition, development, recapitulation) is tempting:

Song – Exposition

Structured Instrumental Crescendo – Development

Free Recapitulation of Song (without vocal)

As in classical sonata form, the opening section of “Starless” sets out a number of musical ideas (themes); the structured instrumental crescendo has something of the free, fantasia, associative, spinning-out, through-composed, quasi-improvisational nature of a development section; and the recapitulation contains both themes of the exposition material in a new, transformed aspect.

The opening “song” section remains in a single key (instead of containing a modulating bridge to a second key as in sonata form); and the structured instrumental section does not develop ideas from the opening song (as a sonata development ordinarily develops themes from the exposition), but rather stands on its own, with entirely new material. But these facts do not disqualify “Starless” from being considered a sonata form in the large sense; Mozart’s sonata forms were one thing, Beethoven’s another, Schoenberg’s something else again, Bartok’s a different species too. As music history went on, sonata form became something quite malleable indeed. Nor do I think it particularly relevant whether or not Fripp and his co-authors set out to compose a sonata form, nor whether some of them even knew what a sonata form was (Fripp and Cross probably did – the others may not have). Brian Eno said once in 1988 with a chuckle, “I didn’t know that piece of mine was in the Dorian mode.” But it was, and he was pleased to know about it with his head, though he had composed it entirely with his ears. The sonata analogy can perhaps enable those who are familiar with the sonata form process in music history to hear “Starless” in a more thorough, integrated fashion.

A more detailed formal outline of “Starless” is shown in Chart 7.

“Starless” as a whole can be seen as a carefully graded swell of energy: by the end of the instrumental crescendo, things have reached such a desperate peak that you think there’s nowhere else to go – but as happens so often in Beethoven codas, for instance, you are seized at that peak moment and hurtled into hyperspace. The recapitulation integrates and transforms the materials of the exposition and the crescendo, forcibly kicking them onto an entirely new level of intensity by means of dynamics, tempo, and orchestration.

The strange melancholy expressed initially in the words of the song (“Old friend charity / cruel twisted smile / and the smile signals emptiness for me / starless and bible black”) is deepened and purified in the recapitulation, when the words are left behind. The restatement of the instrumental first theme and the final minor ending carry the weight of tragedy.

In its dark intensity, in the singularity of its formal conception, in its emphasis on extreme contrasts within a single piece, in its drive to associate specific musical gestures with states, qualities, gradations, and degrees of psychic energy, and – perhaps above all – in the blinding power of its execution, “Starless” is a fulfillment of tendencies in Fripp’s music manifest from the beginning. With the final, hair-raising cadence of “Starless,” the door slams shut on King Crimson’s first period of activity, and, one could say, on the early era of progressive rock as a whole. When Fripp would emerge in the late 1970s with his solo projects, and in the early 1980s with a new, exceptionally streamlined King Crimson, the musical scene would have changed dramatically.