- Franz Liszt: The 100 most inspiring musicians of all time

- Youth and Early Training

- Years with Marie d’Agoult

- Download the best classical scores from our Library.

- Compositions at Weimar

- Eight Years in Rome

- Last Years

- The best of Franz Liszt

Browse in the Library:

Or browse in the categories menus & download the Library Catalog PDF:

Franz Liszt: The 100 most inspiring musicians of all time

Franz Liszt, (b. Oct. 22, 1811, Raiding, Hung.—d. July 31, 1886, Bayreuth, Ger.) Hungarian musician Franz Liszt was one of the greatest piano virtuosi of all time and also was a respected composer of the Romantic period. Among his many notable compositions are his 12 symphonic poems, two (completed) piano concerti, several sacred choral works, and a great variety of solo piano pieces.

Youth and Early Training

Liszt’s father, Ádám Liszt, was an official in the service of Prince Nicolas Esterházy, whose palace in Eisenstadt was

frequented by many celebrated musicians. Ádám Liszt was a talented amateur musician who played the cello in the court concerts.

By the time Franz was five years old he was already attracted to the piano and was soon given lessons by his father. He began to show interest in both church and Gypsy music. He developed into a religious child, also because of the influence of his father, who during his youth had spent two years in the Franciscan order.

Franz began to compose at the age of eight. When only nine he made his first public appearance as a concert pianist at Sopron and Pozsony (now Bratislava, Slovakia). His playing so impressed the local Hungarian magnates that they put up the money to pay for his musical education for the next six years. Ádám took Franz to Vienna, where he had piano lessons with Carl Czerny, a composer and pianist who had been a pupil of Ludwig van Beethoven, and studied composition with Antonio Salieri, the musical director at the Viennese court.

Liszt moved with his family to Paris in 1823, giving concerts in Germany on the way. Liszt’s Paris debut on March 7, 1824, was sensational. Other concerts quickly followed, as well as a visit to London in June.

He toured England again the following year, visiting Manchester, where his New Grand Overture was performed for the first time. This piece was used as the overture to his one-act opera Don Sanche, which was performed at the Paris Opéra on Oct. 17, 1825. In 1826 he toured France and Switzerland, returning to England again in the following year.

Suffering from nervous exhaustion, Liszt went with his father to Boulogne to take seabaths to improve his health; there Ádám died of typhoid fever. Liszt returned to Paris and sent for his mother to join him; she had gone back to the

Austrian province of Styria during his tours.

In 1828, while living mainly as a piano teacher in Paris, Liszt fell ill and subsequently underwent a long period of depression and doubt about his career. For more than a year he did not touch the piano. During this period Liszt took an active dislike to the career of a virtuoso. He made up for his previous lack of education by reading widely, and he came into contact with many of the leading artists of the day. With the July Revolution of 1830 resulting in the coronation of Louis-Philippe, he sketched out a Revolutionary Symphony.

Between 1830 and 1832 he met three men who were to have a great influence on his artistic life. At the end of 1830 he first met Hector Berlioz and heard the first performance of his Symphonie fantastique. From Berlioz he inherited the command of the Romantic orchestra and also the diabolic quality that remained in his work thereafter.

He achieved the seemingly impossible feat of transcribing Berlioz’s Symphonie fantastique for the piano in 1833. In March 1831 he heard Niccolò Paganini play for the first time. He again became interested in virtuoso technique and resolved to transfer some of Paganini’s fantastic violin effects to the piano, writing a fantasia on his La campanella. At this time he also met Frédéric Chopin, whose poetical style of music exerted a profound influence on Liszt.

Years with Marie d’Agoult

In 1834 Liszt emerged as a mature composer with the solo piano piece Harmonies poétiques et religieuses, based on a

collection of poems by Lamartine, and the set of three Apparitions. The lyrical style of these works is in marked contrast to his youthful compositions, which reflected the style of his teacher Czerny.

In the same year, he met the novelist George Sand and also Marie de Flavigny, countess d’Agoult, with whom he began an affair. In 1835 she left her husband and family to join Liszt in Switzerland; their first daughter, Blandine, was born in Geneva on December 18.

Liszt and Madame d’Agoult lived together for four years, mainly in Switzerland and Italy, though Liszt made occasional visits to Paris. He also taught at the newly founded Geneva Conservatory and published a series of essays, On the Position of Artists, in which he endeavoured to raise the status of the artist in society.

Franz Liszt commemorated his years with Madame d’Agoult in the first two books of solo piano pieces collectively named Années de pèlerinage (1837–54; Years of Pilgrimage), which are poetical evocations of Swiss and Italian scenes.

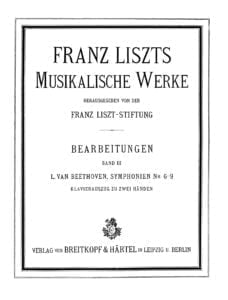

He also wrote the first mature version of the Transcendental Études (1838, 1851); these are works for solo piano based on his youthful Étude en 48 exercices, but here transformed into pieces of terrifying virtuosity. He transcribed for the piano six of Paganini’s pieces—five studies and La campanella—and also three Beethoven symphonies, some songs by Franz Schubert, and further works of Berlioz.

His second daughter, Cosima, was born in 1837 and his son, Daniel, in 1839, but toward the end of that year his relations with Madame d’Agoult became strained and she returned to Paris with the children. Liszt then returned to his career as a virtuoso. For the next eight years Liszt traveled all over Europe, giving concerts in countries as far apart as Ireland, Portugal, Turkey, and Russia.

He continued to spend his summer holidays with Madame d’Agoult and the children until 1844; then they finally parted, and Liszt took the children to Paris. Liszt’s brilliance and success were at their peak during these years as a virtuoso, and he continued to compose, writing songs as well as piano works.

Download the best classical scores from our Library.

His visit to Hungary in 1839–40, the first since his boyhood, was an important event. His renewed interest in the music of the Gypsies laid the foundations for his Hungarian Rhapsodies and other piano pieces composed in the Hungarian style. He also wrote a cantata for the Beethoven Festival of 1845 and composed some smaller choral works.

Compositions at Weimar

In February 1847 Liszt met the princess Carolyne Sayn-Wittgenstein at Kiev and later spent some time at her estate in Poland. She quickly persuaded him to give up his career as a virtuoso and to concentrate on composition.

He gave his final concert at Yelizavetgrad (Kirovograd) in September of that year. Having been director of music extraordinary to the Weimar court in Germany since 1843, and having conducted concerts there since 1844, Liszt decided to settle there permanently in 1848. He was later joined by the princess, who had unsuccessfully tried to obtain a divorce from her husband.

They resided together in Weimar, and this was the period of his greatest production: the first 12 symphonic poems, A Faust Symphony (1854; rev. 1857–61), A Symphony to Dante’s Divina Commedia (1855–56), the Piano Sonata in B Minor (1852–53), the Piano Concerto No. 1 in E-flat Major (1849; rev. 1853 and 1856), and the Piano Concerto No. 2 in A Major (1839; rev. 1849– 61). (A third piano concerto, in E-flat, composed in 1839, was not discovered until 1988.)

During the period in Weimar Liszt also composed the Totentanz for piano and orchestra and revised the Transcendental and Paganini Études and the first two books of the Années de pèlerinage. The grand duke who originally appointed Liszt in Weimar died in 1853, and his successor took little interest in music.

Franz Liszt resigned five years later, and, though he remained in Weimar until 1861, his position there became more and more difficult. His son, Daniel, had died in 1859 at the age of 20. Liszt was deeply distressed and wrote the oration for orchestra Les Morts in his son’s memory.

In May 1860 the princess had left Weimar for Rome in the hope of having her divorce sanctioned by the pope. He left Weimar in August of the following year, and, after traveling to Berlin and Paris, he arrived in Rome. He and the princess hoped to be married on his 50th birthday.

At the last moment, however, the pope revoked his sanction of the princess’s divorce; they both remained in Rome in separate establishments.

Eight Years in Rome

For the next eight years Liszt lived mainly in Rome and occupied himself more and more with religious music. He completed the oratorios Die Legende von der heiligen Elisabeth (1857–62) and Christus (1855–66) and a number of smaller works. He hoped to create a new kind of religious music that would be more direct and moving than the rather sentimental style popular at the time.

In 1862 his daughter Blandine died at the age of 26. Liszt wrote his variations on a theme from the J.S. Bach cantata Weinen, Klagen (Weeping, Mourning) ending with the chorale Was Gott tut das ist wohlgetan (What God Does Is Well Done), which must have been inspired by this event.

The princess’s husband died in 1864, but there was no more talk of marriage, and in 1865 Liszt took the four minor

orders of the Roman Catholic church, though he never became a priest. In 1867 he wrote the Hungarian Coronation Mass for the coronation of the emperor Francis Joseph I of Austria as king of Hungary.

Last Years

In 1869 Liszt was invited to return to Weimar by the grand duke to give master classes in piano playing, and two years later he was asked to do the same in Budapest. From then until the end of his life he divided his time between Rome, Weimar, and Budapest.

His music began to lose some of its brilliant quality and became starker, more introverted, and more experimental in style. His later works anticipate the styles of Claude Debussy, Béla Bartók, and even Arnold Schoenberg.

In 1886 Liszt left Rome for the last time. He attended concerts of his works in Budapest, Liège, and Paris and then went to London, where several concerts of his works were given. He then went on to Antwerp, Paris, and Weimar, and he played for the last time at a concert in Luxembourg on July 19.

Two days later he arrived in Bayreuth for the annual Bayreuth festival. His health had not been good for some months, and he went to bed with a high fever, though he still managed to attend two performances. His final illness developed into pneumonia, and he died on July 31.

The best of Franz Liszt

THE BEST OF LISZT

Liebestraum (Love Dream) Waldesrauschen (Forest Murmurs) from Two Concert Etudes Piano Concerto No. 2 in A major Concerto for Piano and Orchestra No. 1 in E flat minor Concerto for Piano and Orchestra No. 2 in A major Totentanz Hungarian Rhapsody No. 2 Hungarian March.

Browse in the Library:

Or browse in the categories menus & download the Library Catalog PDF: