Browse in the Library:

Or browse in the categories menus & download the Library Catalog PDF:

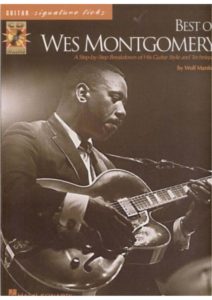

Wes Montgomery: The Top 25 pearls in Jazz history

Wes Montgomery Biography

Full name, John Leslie Montgomery; born March 6, 1923, in Indianapolis, Ind.; died June 15, 1968, in Indianapolis, Ind.

When reading Wes Montgomery Biography, you see that many writers respected him…”Listening to [Wes Montgomery’s] solos is like teetering at the edge of a brink,” composer-conductor Gunther Schuller asserted, as quoted by Jazz & Pop critic Will Smith.

“His playing at its peak becomes unbearably exciting, to the point where one feels unable to muster sufficient physical endurance to outlast it.” Legendary guitarist Joe Pass simply says this about Montgomery’s place in musical history: “To me, there have been only three real innovators on the guitar–Wes Montgomery, Charlie Christian, and Django Reinhardt,” as cited in James Sallis’s The Guitar Players.

Throughout the Wes Montgomery Biography you see that this high praise is a testament to the ability of a dude of contradictions: Montgomery was a musician who never learned to read music, and he enjoyed commercial success rarely afforded to jazz musicians during the 1960s, while suffering critical–and personal–disapproval.

Born John Leslie Montgomery on March 6, 1923, in Indianapolis, Indiana, Montgomery showed no early musical aptitude or desire. At the age of nineteen, shortly after he was married, Montgomery heard a recording of “Solo Flight” by the Benny Goodman Orchestra with Charlie Christian on guitar.

The impression was such that Montgomery immediately purchased an electric guitar, an amplifier, and as many Christian recordings as he could find, listening carefully to the guitar solos and learning to play them note for note. Montgomery’s neighbors complained about the noise, however, so he abandoned the guitar pick in favor of plucking the strings with his thumb.

He found the resulting sound mellow and pleasing. Later, while experimenting with different styles and approaches, he discovered the technique that would become his signature. Gary Giddins, in Riding on a Blue Note, explains: “Almost as an extension of that dulcet, singing tone, he began to work in octaves–voicing the melody line in two registers.”

Within a year, Montgomery played in local clubs, imitating Christian solos. Exposed to other musicians and musical ideas, he developed his own concepts, and in 1948 was asked to join Lionel Hampton’s big band.

As a sideman, Montgomery toured and recorded with this group until 1950 when, having missed his wife and children, he returned home to work as a welder for a radio parts manufacturer.

However, as Rich Kienzle pointed out in Great Guitarists, “His desire to play music…was strong. His shift was from 7 A.M. to 3 P.M.; he’d rest for a while, then play at the Turf Bar from 9 P.M. to 2 A.M., moving to a second gig at another club, the Missile Room, from 2:30 A.M. to 5 A.M.” Montgomery continued this pace for six years, joining the group Mastersounds, composed of his brothers Monk (on bass) and Buddy (on piano and vibraphone), in 1957. A few recordings were made by the group on the West Coast, but they failed to attract much attention, and Montgomery returned home to play in clubs.

In 1959, Montgomery received his big break. While performing at the Missile Room, he impressed saxophonist Cannonball Adderley, who subsequently contacted Orrin Keepnews of Riverside Records. Montgomery was immediately signed and traveled to New York to record his first album, The Wes Montgomery Trio.

“From the beginning of his belated ‘discovery,’ the critical reception ranged from euphoria to hyperbole,” Giddins explained. “No one had ever heard a guitar sound like Wes Montgomery’s.” This critical euphoria reached a fevered pitch with the release of Montgomery’s follow-up album, The Incredible Jazz Guitar of Wes Montgomery (1960). It was not just the sound that Montgomery produced, but, as Sallis says, “the intensity of his music one responded to, the power and personality of it.

When Wes hit a string you felt it, and it wasn’t just a note, a C sharp or a B flat, it was part of a story he was telling you.” This recording won Montgomery the down beat critics’ New Star Award for 1960, and he topped the guitar category in both down beat readers’ and critics’ polls in 1961 and 1962.

For the next couple of years, Montgomery performed and toured with various groups, including his brothers, John Coltrane, Wynton Kelly’s trio, and his own trio. Kienzle remarked that “by this time Wes had gained the eminence due him in the jazz world, producing a steady, high-quality level of music regardless of the context. His flow of ideas, soulful articulation, and effortless technique confronted other influences.”

But in 1964, Riverside Records went bankrupt (following the death of president Bill Grauer), and Montgomery signed with Verve Records, headed by Creed Taylor. This move precipitated Montgomery’s fall from grace with the jazz world and concurrent rise in the popular music world. Giddins explains: “Creed Taylor realized something about Montgomery’s talent: it was octave technique and lyric sound, not his audaciously legato eighth-note improvisations with their dramatic architectural designs, that appealed to middle-of-the-road ears.

Sheet music download here.

So he set Montgomery on a course of decreasing improvisation and increasingly busy overdubbed arrangements, while the octaves, once used so judiciously, became the focus of his new ‘style.’” Montgomery’s 1965 release, Goin’ Out of My Head, was a huge popular success, went gold, and earned him a Grammy award as the best instrumental jazz performance of the year.

Commercial success continued to escalate with subsequent albums on the Verve label, and in 1967, after having moved with Taylor to A&M Records, Montgomery recorded A Day in the Life. The title track not only became a popular hit, but the album became the best-selling jazz album of 1967 and one of the best-selling jazz albums of all time.

Remaking pop hits with a jazz feel increased his audience, but decreased his acclaim in jazz circles. Adrian Ingram, in an article for Jazz Journal International, noted that “hard core jazz fans began to desert him, complaining bitterly of over-orchestrated arrangements, sub-standard material (pop tunes) and constricted solo space.” Sallis offered an explanation for his decline: “He was a victim of his own popularity, or of the trivialization of his talent, depending on how you perceive it, and as a result that talent went largely unheard for the last years of his life.”

Montgomery was aware of the growing dissatisfaction in the jazz community with his supposed commercialization, and he tried to make a distinction between his earlier work and his more popular work. “There is a jazz concept to what I’m doing, but I’m playing popular music and it should be regarded as such,” Montgomery said, as quoted by Giddins.

His approach to music had always been one of feeling rather than one of technique. His inability to read music led to his development of a fine ear; he heard music rather than saw it on a page. And this was most important in his relation with his audience. “Wes believed that the music should be communicated, that the audience was part of the band, and the feeling of the music was more important to him than playing every note correctly,” Jimmy Stewart wrote in Guitar Player.

Regardless of the style of, or the audience for, the music, Montgomery played with feeling and conviction. Of Road Song, his last recording for A&M before his death, down beat ‘s Pete Welding said, “He couldn’t play uninterestingly if he wanted to. Time and time again throughout this collection his supple sense of rhythm, his choice and placement of notes, his touch and tone raise what might have been in lesser hands merely mundane to the plane of something special, distinctive, masterful.”

Even with his quoted defense of playing popular music, Montgomery, as Ingram noted, “began to feel trapped by both the music business in general and non-jazz audiences who would tolerate only note perfect renditions of the most popular tunes from his Verve albums.”

Montgomery longed to return to the playing of his earlier style. This was no more evident than when he performed live. A month before Montgomery’s death, Giddins saw him perform and described what he heard: “Surrounded by four rhythm players, his regular group, he immediately shot off a single chorus of ‘Goin’,’ and followed it with the most fiery, exquisite set of guitar music I’ve ever heard…. Clearly, he had compromised only on disc and would eventually be recorded more seriously.” Unfortunately, this did not occur. At the peak of his career, Montgomery suffered a fatal heart attack in his hometown on June 15, 1968.

“While Montgomery’s place in jazz history was earned through his early recordings–his jazz recordings–his talent was encompassing enough to enable him to take on the requirements of ‘commercial’ music and execute it with utter elan, unerring taste, musicianship, and true distinction,” Welding wrote.

In a review for down beat of a posthumous release, Don DeMicheal offered this statement on Montgomery’s lasting ability: “Montgomery could do no wrong when his muse was hot upon him, and it often led him to try and accomplish things that few others could even conceive.”

But it is perhaps this quote from Ingram that succinctly defines the achievements and losses of Montgomery: “Even when he was immersed in blatantly commercial surroundings, Montgomery never lost his ability to create sophisticated, tasteful jazz. He could turn tap water into vintage wine, though it is sad he was forced to do so, so often.”

Wes Montgomery – Wes’ Best / Wes Montgomery and his Brothers (Full Album)

Browse in the Library:

Or browse in the categories menus & download the Library Catalog PDF: