Come join us now, and enjoy playing your beloved music and browse through great scores of every level and styles!

Can’t find the songbook you’re looking for? Please, email us at: sheetmusiclibrarypdf@gmail.com We’d like to help you!

Rachmaninoff’s Piano Concertos performance

Rachmaninoff’s Piano Concertos No.2 and No.3 are probably two of the most popular pieces among the composer’s five concerto works. They were written in a similar style and harmonic language, but are still different in many aspects. The Piano Concerto No.3 is famous (or notorious) for its technical demands. It is much harder than No.2.

Please, subscribe to our Library.

If you are already a subscriber, please, check our NEW SCORES’ page every month for new sheet music. THANK YOU!

The characters of its piano writing – such as extended chords, polyphonic textures, and abundant notes – all reflect Rachmaninoff’s own pianistic technique and physical advantages, which makes the concerto so personalized that it is hard for others to play. Even for the composer himself, the concerto was still a challenge. Cyril Smith comments that:

It is the most technically exhausting, the most physically strenuous of all. It has more notes per second than any other concerto, a lot of the music being terribly fast and full of great fat chords. Many performances are marred because the soloist simply cannot carry on, and Rachmaninoff himself, after playing it one night at the Queen’s Hall, came off the platform shaking his hands up and down and muttering, “Why have I written so difficult a work?” (Cyril Smith, Duet for Three Hands (London: Angus and Robertson, 1958), 82).

Best Sheet Music download from our Library.

The difficulty of the concerto has probably also influenced pianists’ interpretation and preparation process. If the technical demands are so high, then it is imaginable that pianists would be more interested in listening to the composer’s recording to see how he executed those difficult passages, or how he wished them to be executed. This is like cooking: if we are preparing a simple dish, it is not always necessary to check all the details of cooking processes in the recipe; if the course is complicated, however, then it is best to see an example first to know how it could be properly made.

If pianists listen to the composer’s recording more seriously, or intentionally take his version as a guideline, it is conceivable that they will be more influenced by his interpretation. When Cyril Smith was recording this concerto, although he thought he knew it ‘upside down and inside out’, Rachmaninoff’s recording still deeply influenced him:

After a long session at the recording studios the master disc was played back to me, as usual, and I thought it sounded good enough to be release. Then, suddenly, I had second thoughts and asked to hear a recording of Rachmaninoff playing the same work. Immediately I knew that mine would not do, and I told the artist manager that I have changed my mind.

Although Smith writes that he spent another three weeks practicing and then recorded it again, and he never mentioned his discussion with the composer regarding the interpretation of the concerto in his autobiography, at least this story reveals that he was influenced by the composer’s recording of the piece.

The situation probably can be seen in other pianists’ learning or recording processes, at least in the performance of Byron Janis, which we are going to see later.

But there is another major difference between the two concertos as regards performance history.

Unlike the case of the Piano Concerto No.2, Rachmaninoff was not the first pianist to record this piece, nor was he the only performer who strongly influenced how other pianists interpreted this concerto. His younger colleague Vladimir Horowitz’s version of 1930 was the world premiere recording of the concerto, made nine years before the composer’s.

Before going to the States, Horowitz toured this concerto in Europe for years with great success, and he also made his American debut by playing this concerto. After he made his sensational Carnegie Hall debut by Tchaikovsky’s Piano Concerto No.1, his formidable technique successfully captured Rachmaninoff’s attention, and later they had the first private meeting in 1928.

Horowitz used this opportunity to play the Piano Concerto No.3 for the composer, and in the end he not only surprised Rachmaninoff but also earned his respect and lifetime friendship. Rachmaninoff highly appreciated Horowitz’s interpretation of the concerto. It is a well-known story that the composer remarked publicly after the 7th August 1942 Hollywood Bowl performance that:

‘This is the way I always dreamed my concerto should be played, but I never expected to hear it that way on Earth.’ (Michael Scott, Rachmaninoff Brimscombe Port: The History Press, 2008), 145-146).

Although a recording of this concert has not yet been found, we have Horowitz’s live performance of the concerto in the previous year (with Sir John Barbirolli and the New York Philharmonic Orchestra). He played this concerto within thirty-three minutes and forty-nine seconds – almost the shortest version ever.

If Horowitz also played the concerto similarly one year later in Los Angeles (judging by Horowitz’s performances in general around these two years, no significant change took place during this period), we can probably say that this 1941 performance is very close to Rachmaninoff’s ‘dream version’ of the piece in his mind.

Because Horowitz’s performance of the concerto was highly admired by the composer, his recording of it also could also have become an important reference for many of his colleagues, taking on a similar authoritative status to the composer’s.

Rachmaninoff and Horowitz played the concerto differently in temperament, but had two aspects in common. First, they played it at a very fast speed. Secondly, they cut many sections (but their cuts are not all the same). The latter gives us an opportunity to observe whether their recordings are actually ‘authoritative renditions’.

We might assess their influence through deletions: have other pianists ever made the same or similar deletions as they did? Because their cuts are not all the same, we can also trace whether a pianist was more influenced by Rachmaninoff’s recording or by Horowitz’s by comparing the cuts the pianist made.

There is no clear explanation for why Rachmaninoff made several deletions in the concerto in his recording. He made five cuts altogether. One might suppose that it was to ensure they fitted onto the 78s, but it may be also simply that he wished to do so. The reason which supports the latter theory is that the concerto was recorded on five discs of 78rpm records, but side ten is blank.

If Rachmaninoff had wished, there would have been another four minutes for him to record onto. In addition, the way Rachmaninoff separated and recorded the movements implies how he wished the performance to sound (see Table 5-3, page 433).

For example, side 2 ends at bar 221 of the first movement, in the middle of a musical phrase. Logically, had he wanted to end the side with a complete musical sentence (as most pianists did) and then start the next on side 3, there would have been enough room to do so.

However, stopping in the middle of a phrase can prevent one ending with a ritardando. When the two sides match together, as we hear on CD now, one cannot notice that the phrase was recorded separately. This trick shows Rachmaninoff’s experience and wisdom as an old hand recording artist, and the performance in the recording is probably what he wished to present, without compromising the time limit of the 78s.

In addition, in an interview published in Gramophone magazine in 1931, Rachmaninoff recalled how he recorded his Piano Concerto No.2, which reveals his recording experience and strategy:

Recording my own Concerto with this orchestra was an unique event. Apart from the fact that I am the only pianist who has played with them for the gramophone, it is very rarely that an artist, whether as soloist or composer, is gratified by hearing his work accompanied and interpreted with so much sympathetic co-operation, such perfection of detail and balance between piano and orchestra.

These discs, like all those made by the Philadelphians, were recorded in a concert hall, where we played exactly as though we were giving a public performance. Naturally, this method ensures the most realistic results, but in any case, no studio exists, even in America, that could accommodate an orchestra of a hundred and ten players.

If the composer maintained the same working method eight years later, when he recorded his Piano Concerto No.3, and also ‘played exactly as he was giving a public performance’, then those five cuts in the performance were probably what he wished to have.

In fact Rachmaninoff, in his lifetime, allowed cuts to be made to his large-scale works during performances, such as the Symphony No.2, Variations on a Theme of Chopin, and Variations on a Theme of Corelli. He even shortened his Piano Sonata No.2 (composed in 1913) and published the revision in 1931. This is mainly because Rachmaninoff was seriously concerned about audiences and critics, and was not confident in his music writing.

When he gave the world premiere of the concerto in New York in 1909, critics from several important newspapers – such as the New York Herald, the New York Sun, and the New York Daily Tribune – all argued that the concerto was too long.

Although we have no evidence to confirm that Rachmaninoff played the whole concerto without cuts at that concert, it is certain that he never played an uncut performance of this piece later in his life. Horowitz left three commercial recordings and several live performances recorded, and all of them are with cuts.

From these two case studies, we can see that the general trend over the generations was for pianists to become more faithful to the score and to play Rachmaninoff’s music in slower tempo.

It seems that more and more pianists have started to use Rachmaninoff’s playing as a reference after the digitised reissues of his Piano Concerti No.2 and No.3 (1987) and complete recordings (1992). Through the case studies in Chapters Four and Five, we have found several major trends through the generations. However, the bewildering fact is that pianists are very inconsistent in their interpretative approaches.

Soviet and Russian pianists have a long tradition of being faithful to the score: they still do so in the Piano Concerto No.2, but many of them decide to follow the cuts in Rachmaninoff’s rendition, which sacrifices the completeness of the work. The same pianist can be faithful and conventional in the No.2 and also be unconventional in the No.3. Does this mean that pianists are actually very selective about whether to be faithful?

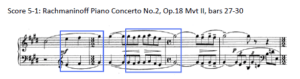

Further light can be shed on this question by examining pianists’ phrasing style in a passage from the second movement from Rachmaninoff’s Piano Concerto No.2. It is the first theme’s first appearance in the piano solo part. In the score, Rachmaninoff marked a bel canto style, crescendo-decrescendo dynamic indication in bar 28 (the second blue square in the score example score 5-1). In the next bar, the closing phrase of the sentence, he marked decrescendo, in the manner of the traditional Russian singing phrase:

It is clear that it is Rachmaninoff the composer who has obviously influenced the interpretation of his works through his recordings. The reasons are twofold: he was a truly remarkable pianist, and the sound quality of his recordings is also good enough to record his pianism and music-making. Recorded performances, as the case of the ‘authoritative renditions’ has shown, can have a strong musical and even cultural influence.

Frequently, we have seen that composers want what is written on the page until they hear a really convincing alternative view, and then they often love that difference. That is why Horowitz’s performance of Rachmaninoff’s Piano Concerto No.3 is different from the composer’s rendition, but Rachmaninoff loved it even more. When Krystian Zimerman asked Lutosławski how he would like him to perform his Piano Concerto, the composer replied:

“I don’t know. I’m curious about what this concerto will develop into. The piece is like my child. I gave it life, but it’s not my possession. It will grow and develop on its own course; it will find its own life. I’d very much like to know what it would turn out to be like in another twenty years. Too bad I won’t be able to see for myself.”

Rachmaninoff’s piano music is great enough to provide variety, room, and possibilities for musicians to explore. While people still love his music, the evolution of interpreting his works will never stop.

Horowitz Rachmaninoff 3rd Concerto Mehta NYPO 1978

Browse in the Library:

Or browse in the categories menus & download the Library Catalog PDF: