Come join us now, and enjoy playing your beloved music and browse through great scores of every level and styles!

Can’t find the songbook you’re looking for? Please, email us at: sheetmusiclibrarypdf@gmail.com We’d like to help you!

Table of Contents

How To Play Bebop (David Baker) for all instruments (Vol. 1 to 3)

Preface to Vol. 1

Of all the styles to emerge from jazz, perhaps the most important and pervasive in terms of influence and consequence is that body of music which had its inception in the early 1940s in the playing of its two main giants, Dizzy Gillespie and Charlie Parker, the music which is known as bebop. In the ensuing years the music and its musicians have not only endured but grown in stature and influence.

Please, subscribe to our Library.

If you are already a subscriber, please, check our NEW SCORES’ page every month for new sheet music. THANK YOU!

Since Diz and Bird, virtually every voice in jazz has demonstrated an indebtedness to them and the exciting new style that they pioneered, I think that one could say without fear of contradiction that bebop is the common practice period of jazz.

Very little music in popular idioms has escaped its influence. Older styles that coexist with it have absorbed many of its characteristics and strengths and music of its vitality. Almost all later styles-cool, hard bop, funky, contemporary mainstream ( 4ths, pentatonics, angularity, etc.), thirdstream, fusion, etc.-have all borrowed liberally from the language, structure, syntax, grammar, gestures, etc., of bebop.

For years, it has been an unwritten law that the understanding of and ability to function comfortably in bebop represents a solid basis for dealing with almost all other jazz styles; and even though many of the styles of”free jazz” seemed to have leaped backwards to earlier styles for their major impetuses, the vast majority of today’s players came from bebop or one of its myriad offshoots.

One need only observe the ever important groups such as those of the master Dizzy Gillespie, Art Blakey’s Jazz Messengers, Horace Silver’s groups, groups led by such musicians as J. J. Johnson, Freddie Hubbard, Woody Shaw, Sonny Rollins, Dexter Gordon, Stan Getz, McCoy Tyner, James Moody, Wynton Marsalis, and others, to realize that bebop is still the main center of the jazz universe.

In our major educational institutions, the bebop flame continues to bum brightly as we see generation after generation of young talent emerging with a healthy respect and solid understanding of this rich tradition. To be sure, many of these players will choose styles such as fusion, various areas of free improvisation, etc., but their musical vistas will be infinitely wider for their having come to terms with bebop.

Perhaps, saxophonist-composer educator-bandleader Frank Foster really hit the nail on the head when he referred to the music in this way: “Bebop, the music of the future.”

Best Sheet Music download from our Library.

Part I

THE BEBOP SCALES

From the early l 920s, jazz musicians attempted to make their improvised lines flow more smoothly by connecting scales and scale tones through the use of chromatic passing tones. In a detailed analysis of more than 500 solos by the acknowledged giants from Louis Armstrong through Lester Young and Coleman Hawkins, one is aware, first, of the increased use of scales ( as opposed to arpeggios and chord outlines) and then the increasing use of chromaticism within these scales.

An unusual fact about this increased chromaticism is that, despite the frequent re-occurrence of certain licks or patterns, no discernible design with regard to how the extra chromatic tones are added emerges. The overall impression is a somewhat arbitrary or random use of chromaticism. When one listens to the great players from the distant and near past, one of the main things that tends to “date” their playing ( aside from technological improvements in recording techniques, changes with regard to harmonic and rhythmic formulae, etc.) is this lack of unanimity with regard to the use of melodic chromaticism.

From his earliest recordings, Charlie Parker can be observed groping for a method for making the modes of the major scale sound less awkward and for rendering them more conducive to swing and forward motion. Gradually, in a systematic and logical way, he began using certain scales with added chromatic tones. Dizzy, approaching the scales from an entirely different direction, began utilizing the same techniques for transforming them.

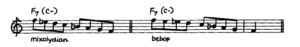

These scales became the backbone of all jazz, from bebop to modal music. A study of numerous representative solos from the bebop era yields a set of very complex governing rules that have now been internalized and are a part of the language of all good players in the bebop and post-bebop tradition. Very simply stated, the added chromatic tones make the scales “come out right.” Play a descending mixolydian scale and then play the bebop version of the scale and see how much smoother the second scale moves.

There are a number of reasons……. (cont.).

Dizzy Gillespie – Bebop

Trumpet – Jon Faddis Tenor Saxophone – Andres Boiarsky Piano– Cyrus Chestnut Bass– John Lee Drums– Ignacio Berroa

The Dizzy Gillespie Alumni All-Stars – Dizzy’s 80th Birthday Party!