Come join us now, and enjoy playing your beloved music and browse through great scores of every level and styles!

Can’t find the songbook you’re looking for? Please, email us at: sheetmusiclibrarypdf@gmail.com We’d like to help you!

Original Sheet Music of 24 Jazz Standards

24 Original Sheet Music of 24 Jazz Standards (Compiled by Ethan Iverson and Mike Kanan)

Most Jazz Standards were originally written for musical theatre, movies, and other kinds of general entertainment in the 1920s, ‘30s, and ‘40s. At that time, sheet music was a thriving business, and nearly all these songs were published in piano/vocal scores, often as a single sheet with a colorful cover, like “I Should Care” shown above. (The relevant phrase “Tin Pan Alley” refers to a particular area of New York City where many music publishers were crammed on top each other like tenement housing.)

Best Sheet Music download from our Library.

Mike Kanan and I share an interest in this jazz standards sheet music. Over the years, Mike has given me a lot of harmonic “secrets” lurking in original published scores. Together we came up with the following casual selection: Mike had most of the songs in his extensive collection, contained in anthology songbooks or photocopied from libraries.

You used to be able to go to Colony Music in Manhattan and get nearly any song in a single sheet or an anthology — their massive inventory was cross-indexed — but Colony closed its doors in 2012.

Colony could have easily been where McCoy Tyner went to get the music for John Coltrane and Johnny Hartman. In pictures from the session, single sheets are spread out over Van Gelder’s piano. To make the obvious inference: Tyner looked at the sheets, and then made up reharmonizations that fit the style of the session at hand.

The sheet music is just one reference. It’s no “urtext” of a song in the manner of European classical music. Some of the composers may have been more like a folk composer, such as Irving Berlin, who apparently could not write out a piano score. Other prolific composers may not have overseen each piece of piano/vocal sheet music. More tangibly, a comparison of the sheet with a historical “straight” (non-jazz) performance on record or in a movie will show many differences.

Please, subscribe to our Library.

If you are already a subscriber, please, check our NEW SCORES’ page every month for new sheet music. THANK YOU!

Still, the melody and the lyrics are correct on a piece of published sheet music. (Before improvising on the melody, it is helpful to know the original melody.) And the harmonies themselves are also a valid opinion — most importantly, an opinion that does not rehash the received wisdom of jazz lead sheets generated since the ‘70s. In The Story of Fake Books: Bootlegging Songs to Musicians, Barry Kernfeld explains how chords symbols first came from ukulele charts. There was a big ukulele boom in the 1920s, and publishers added uke chords to the piano scores in an attempt to generate more sales.

There was no reason to include the bass motion in a uke chart, and this absence of proper bass motion still haunts lead sheets to this very day. Someone like Ron Carter is popular partly because Carter can find inversions and melodic bass lines despite being handed charts that default to constant root position.

(ukulele chords with incorrect bass motion from “All of Me”)

One of the selling points for a sheet music song was the verse. With a few exceptions, common practice instrumental jazz has done away with the verses. While I have included the verses in the pdf, I do not play them in my little videos — except “Lush Life,” which is mandatory. Mike is a celebrated accompanist of singers, and he probably would have included more of the verses in the videos, many of which are beautiful.

When I read through the Jazz Standards’ sheet music, I don’t play them as jazz. I try to play them as if I was accompanying a musical theatre singer or for a Hollywood temp track.

Not all of the composers knew much about jazz: in some cases, they actively disliked jazz. Ironically, these tunes are still around thanks to the many immortal jazz musicians who have endlessly reinvented these themes with improvisation and an African aesthetic. That is why they have become JAZZ STANDARDS!!

24 Jazz Standards:

1. After You’ve Gone (Turner Layton & Henry Creamer). Turner Layton was an African-American composer. In 1918 New York was still a segregated society, and the thriving black musical theatre world was totally separate from nascent Broadway. Spreadin’ Rhythm Around: Black Popular Songwriters, 1880-1930 by David A. Jasen and Gene Jones is a helpful book when trying to assess this era. Layton’s bass inversions in “After You’ve Gone” are essential to the harmonic structure; this song was also one of the first that jazzers began playing as “double time.”

https://videopress.com/embed/05iIplJr

2. All of Me (Gerald Marks & Seymour Simons). Some nice inner voices and a melodic A-flat four bars from the end that is rarely played.

played.

3. All the Things You Are (Jerome Kern & Oscar Hammerstein II). For all its familiarity, a song hard to harmonize comfortably, as the melody is frequently parallel. The really surprising chord is the last bar of the bridge. I still play C7 myself, but there’s certainly an argument for the alternate. One time at a club, Barry Harris called Mike over and asked him, “What is the last chord of the bridge of ‘All the Things You Are?’” Mike said, “As far as I know, it’s A-flat augmented.” Barry exclaimed in response, “A-ha! I just knew it wasn’t C7!”

4. April in Paris (Vernon Duke & Yip Harburg). Vernon Duke was a serious classical composer and “April in Paris” is one of the most outlandish pieces in this collection. Just awesome. I can hear the future Thelonious Monk in this 1932 song — and, of course, nobody played “April in Paris” better than Monk.

5. But Not For Me (George & Ira Gershwin). Many jazz performances start on F7, but Gershwin just wrote E-flat — which then sets up a change to F7 (in second inversion) on the next phrase. Unlike some of the composers collected here, Gershwin’s idiosyncratic harmonic language has been influential on the very content of jazz. In the lobby of Porgy and Bess at the Met, I ran into Bill Charlap. I joked to him, “I bet you are checking out these voicings.” Bill replied seriously, “Porgy and Bess has every voicing you will ever need.”

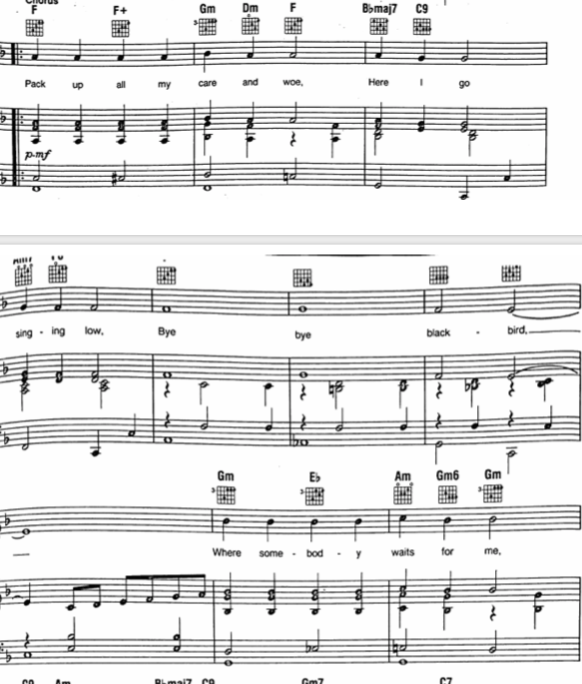

6. Bye Bye Blackbird (Ray Henderson & Mort Dixon). Included because there is no single agreed upon set of changes, which is part of its charm: In the hands of Miles Davis or John Coltrane, “Bye Bye Blackbird” is almost “modal” in a tonal context. I had never seen the original sheet until Mike produced a copy, and it wasn’t quite what I expected.

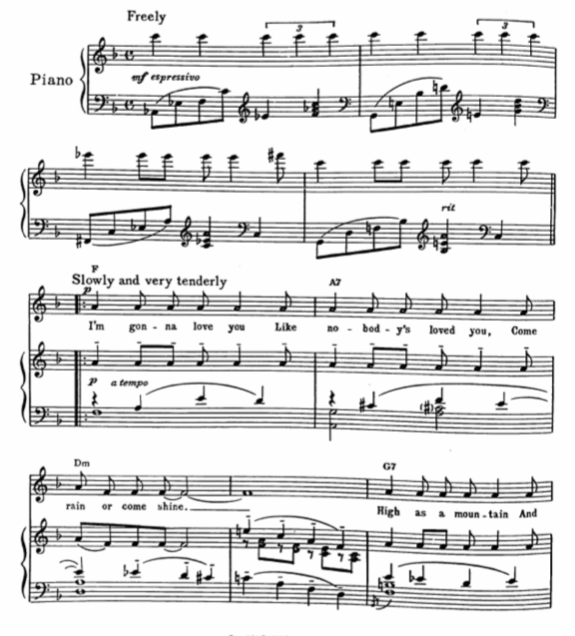

7. Come Rain or Come Shine (Harold Arlen & Johnny Mercer). Arlen worked at getting some kind of synthetic “blues” in his pop songs, a proposal unhesitatingly accepted by many of the greatest black jazz musicians. The piano part here is quite difficult, more like reading a Bill Evans transcription with rootless voicings than a standard pop song. Arlen’s original rich progressions are far from being common jazz practice for “Come Rain or Come Shine.”

8. Gone With the Wind (Allie Wrubel & Herb Magidson) Not related to the Max Steiner music for the famous movie. Jazzers like this one for the pleasant II/V’s, but the original piano score is a dramatic tone poem.

9. How Deep is the Ocean (Irving Berlin). Great set of lyrics (it’s always good to notice the lyrics). This version offers more unique bass motion than we are accustomed to today.

10. I Could Write a Book (Richard Rodgers & Lorenz Hart). Fred Hersch told me, “Nobody got more out of a major scale than Richard Rodgers.” The even plain of C major is interesting, jazzers usually fill in the spaces with turnarounds, but then the move to G major — in first inversion, thank you very much — is pure drama.

11. I Fall In Love Too Easily (Jule Styne & Sammy Cahn). An unusually short ballad, just 16 bars of rarefied beauty.

12. I Hear a Rhapsody (George Fragos, Jack Baker & Dick Gasparre). A vague disquiet always hangs over this song at a jam session. It’s fun to blow on, but do those familiar changes really fit the melody? Aha! The sheet has interesting answers.

13. I Remember You (Victor Schertzinger & Johnny Mercer). Jazzers play a big Tadd Dameron-style II/V in bar two, and that’s great, but it’s interesting that Schertzinger simply wrote a diminished chord.

14. I Should Care (Axel Stordahl, Paul Weston & Sammy Cahn). Like “April in Paris,” I can draw a straight line from this spectacular 1944 sheet to Thelonious Monk, who repurposed the song to such surreal effect.

15. It Could Happen to You (Jimmy Van Heusen & Johnny Burke.) Playing through Van Heusen’s sheet in G is so sensible compared the mess in E-flat I’ve perpetrated at so many casual sessions over the years…

16. I Wish I Knew (Harry Warren & Mack Gordon). Total Gil Evans! (Or really, Debussy to Gil Evans.)

17. Just Friends (John Klenner & Sam M. Lewis). Not that surprising until the end — where I finally play the melody correctly for the first time in 30+ years. Drat!

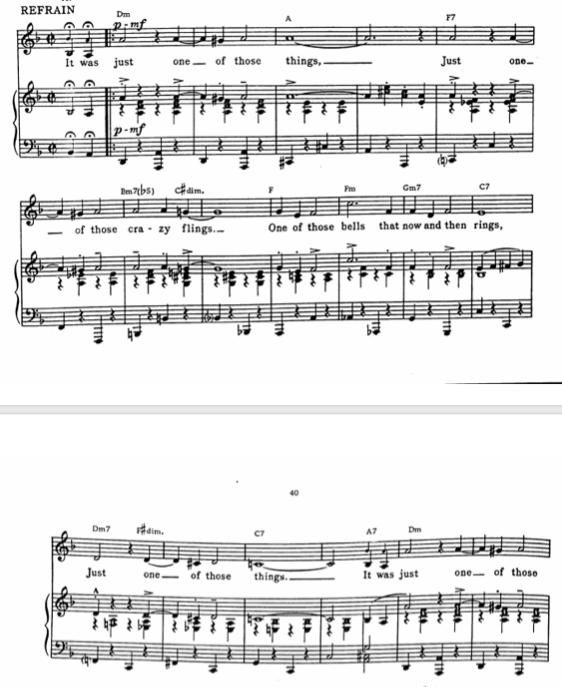

18. Just One of Those Things (Cole Porter). I wanted to include at least one up-tempo song, although these are frankly less hip to do as “non-jazz” than the ballads, and my piano playing suffers a bit as a result. The end of the bridge is interesting, a moment where even professionals can be at a loss. Porter ends in C and simply restarts. Cedar Walton would harmonize the C (in the melody) with G minor, certainly a valid choice.

19. Lush Life (Billy Strayhorn). A 1948 recording exists of Strayhorn and Kay Davis performing this most epic of epic ballads “as is” (following this chart closely) at Carnegie Hall.

20. Memories of You (Eubie Blake & Andy Razaf). Blake had a unique two-part career, first as a song composer, then as a ragtime pianist. “Memories of You” has been recorded over 700 times.

21. My Ideal (Newell Chase, Richard A. Whiting, & Leo Robin). This short number is surprisingly popular with students. I was curious to see the original sheet, and it proved to be a delectable confection indeed.

22. Prelude to a Kiss (Duke Ellington, Irving Gordon & Irving Mills). Generally, the Tin Pan Alley sheet music representations of Duke Ellington’s sublime output are pretty bad. Either the composer didn’t offer any oversight, or he didn’t want anyone to learn his music accurately from a chart. (Ellington was a master of hoarding secrets.) “Prelude to a Kiss” is better than most, although it feels awkward to read through the whole 32 bars with no variation, for that simply isn’t the Ellington style. Still, this is a better starting point than the lead sheet I first learned from the Real Book…

23. Stella By Starlight (Victor Young & Ned Washington). I believe Bill Evans gave us the standard changes we all use for “Stella” on a wonderful 1958 record with Miles Davis and John Coltrane. (Evans self-deprecatingly called himself a “Tin Pan Alley pianist,” and one can learn a lot of Evans’s secrets when playing through stacks of original sheet music.) The later Miles records with Herbie Hancock also use the “Bill Evans changes.” Among the many other truly great versions of “Stella” following the Davis/Evans/Hancock thread include two iconic trios, Joe Henderson/Ron Carter/Al Foster and Keith Jarrett/Gary Peacock/Jack DeJohnette.

All that is to say that I am not against jazz “common practice” chord changes. Those changes are usually there for a reason: see the above list of masterpiece recordings.

However, in 2021, there may not be too much room left for just going for it on “Stella,” jam-session style, in the vein of the consecrated 20th-century jazz masters. The published chart of “Stella” is older than the Bill Evans changes, but, paradoxically, it may sound fresher to us today.

24. Willow Weep for Me (Ann Ronell). Ronell’s immortal song is the only “blues ballad” in this selection. It might feel like a blues ballad is more like a folk tune, but as a serious composer, Ronell fought for every note on her page. As with Arlen, heavy black practitioners accepted Ronell’s gloss on the blues: “Willow Weep for Me” is one of the most-recorded blues ballads of all time.