Come join us now, and enjoy playing your beloved music and browse through great scores of every level and styles!

Can’t find the songbook you’re looking for? Please, email us at: sheetmusiclibrarypdf@gmail.com We’d like to help you!

Table of Contents

Jerry Goldsmith (sheet music in the #smlpdf)

Best Sheet Music download from our Library.

Please, subscribe to our Sheet Music Library.

If you are already a subscriber, please, check our NEW SCORES’ page every month for new sheet music. THANK YOU!

Jerry Goldsmith 1979 Star Trek The Motion Picture 01 Theme

Jerry Goldsmith – Alien (piano sheet music)

Jerry Goldsmith – Papillon (Piano)

Jerry Goldsmith – Poltergeist (piano)

Jerry Goldsmith – Star Trek – First Contact (Piano solo)

Jerry Goldsmith Chinatown Love Theme (Guitar chords)

The Last Run (Jerry Goldsmith)

The Mummy (Jerry Goldsmith)

Jerry Goldsmith Basic Instinct – Main Theme

Jerry Goldsmith First Blood It’s a long road piano solo

Jerry Goldsmith Star Trek Theme piano solo

Jerry Goldsmith The Russia House Katya Jerry Goldsmith piano solo

Top 10 Soundtracks by Jerry Goldsmith

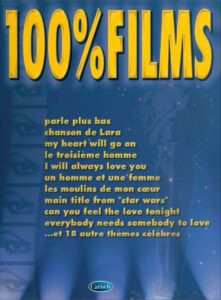

Track List:

Allien (1978) dir. Ridley Scott 0:09 Patton (1970) dir. Franklin J. Schaffner 2:21 The Wind and the Lion (1975) dir. John Milius 4:26 Planet of the Apes (1968) dir. Franklin J. Schaffner 6:55 The Mummy (1999) dir. Stephen Sommers 9:13 Mulan (1998) dir. Tony Bancroft & Barry Cook 10:43 Star Trek: The Motion Picture (1979) dir. Robert Wise 13:06 Poltergeist (1982) dir. Tobe Hooper 14:30 Chinatown (1974) dir. Roman Polański 16:49 Basic Instinct (1992) dir. Paul Verhoeven 18:48 The Ghost and the Darkness (1996) dir. Stephen Hopkins 20:51 Gremlins (1984) dir. Joe Dante 22:53 Innerspace (1987) dir. Joe Dante 25:16 L.A. Confidential (1997) dir. Curtis Hanson 26:33 The Omen (1976) dir. Richard Donner 28:10

Jerry Goldsmith

He was born in Los Angeles (USA), on February 10, 1929, and died in the same city, on July 21, 2004. Composer with a career that lasted more than 50 years in which he participated in countless masterpieces of the cinema, whose contribution was in many cases decisive in achieving that qualification. An Oscar , six Grammys, nine Golden Globes, four Baftas… are nothing more than a confirmation of the immense quality and almost incomprehensible nature of his entire career.

Jerrald King Goldsmith was born in Los Angeles and, unlike many other composers, to parents who on this occasion had absolutely no relationship with music. At the age of six he was already playing the piano, but it would not be until many more years later when he would begin to take classes and train as a pianist. At the age of 16 he began studying theory and counterpoint with the Italian composer Mario Castelnuovo-Tedesco, who was also a teacher of such relevant film musicians as Henry Mancini , Nelson Riddle , André Previn and John Williams in the cinema

In 1945, Goldsmith saw Alfred Hitchcock’s Spellbound ‘s soundtrack , and Miklós Rózsa captured his attention so powerfully that he decided to try to enter the world of cinema one day. Later, he enrolled at the University of Southern California, where Rózsa taught and hoped to be her student, but ultimately decided on the music program at Los Angeles City College, where he multiplied his activities, becoming an assistant of the choir director, accompanying pianist and assistant conductor.

In 1950, he found work in television, specifically at CBS, in its music department. There he began to compose music for radio programs. Little by little he progressed until he became the composer of several television programs, as well as some series, such as some episodes of The Twilight Zone . He remained in television for ten years, after which he accepted producer Norman Felton’s offer to join Metro Goldwyn Mayer, and begin working on the production company’s premieres. His first film was Black Patch, a western of little notoriety, and Goldsmith divided his activity between cinema and television, for which he continued to collaborate on several series on different networks.

Thus, the composer gained experience and level thanks to series such as Dr. Kildare or Thriller , and entered the 1960s as a firm promise for the future in the film music scene. Thanks to these television works he caught the attention of none other than Alfred Newman . The veteran and legendary composer was impressed by Goldsmith’s work, and recommended him to Universal.

Thus, in 1962 he would compose the music for Lonely are the Brave , a western by Kirk Douglas with a script by Dalton Trumbo, a soundtrack in which he was not limited to the typical melodies of the genre, but also influenced the psychology of the protagonists and in tracing an intimate portrait of them. In that same year he also managed to be selected by none other than John Huston to take on the task of musically portraying Sigmund Freud in Freud . For this one, Goldsmith dared to experiment (a constant in his later career) with an atonal and dense score that delved into the unconscious and the dream world. This daring was rewarded with his first Oscar nomination (losing to Maurice Jarre and his Lawrence of Arabia ) and his definitive establishment in Hollywood and the world of big productions.

The following year would also be of great importance for Goldsmith, because he would compose the music for a film that did not have much impact, The Stripper (63). But if it was important, it was because it was his first collaboration with director Franklin J. Schaffner, a filmmaker with whom he had a very long and fruitful collaboration. The rest of the decade would define him as one of the most talented composers on the American scene. Although he continued to collaborate from time to time on television (with the memorable The Man from UNCLE in my memory), cinema would be the field where he continued to grow more and more, and where he continued to amaze directors and viewers, since no genre was beyond him. resisted, achieving notable and, in some cases, outstanding results.

Westerns like Río Conchos (64), thrillers like Seven Days in May (64), war films like In Harm’s Victory (65), The Blue Max (66) or The Sand Pebbles (66), or dramas like A Patch of Blue ( 65) benefited from having powerful, subtle, brave and magnificently executed compositions that gave an idea of Goldsmith’s immense talent. But in 1968 his career took another leap forward. That year a science fiction film called The Planet of the Apes , directed by Schaffner, who wanted to have Goldsmith for the musical part. The composer surprised everyone with a very risky and experimental music, far from fanfares and large orchestras, which impressively portrayed the arid, desperate and distressing tone of the film. A score where the primitive, the primary and the strange was the backbone, a composition with percussions and sounds that accompanied Charlton Heston (and the viewer) on his journey through that strange planet. Another great triumph, another Oscar nomination and Goldsmith was installed in the league of the greatest, of the masters who dared to go one step further in terms of making films with music, and to innovate in important productions with stars.

The 70s began with a new collaboration between Schaffner and Goldsmith: Patton (70), the biopic of the famous American general in World War II. The composer made a perfect portrait of the character, with a central military march to define him and secondary themes that delved into the eccentric and controversial edges of the famous soldier. New nomination and new success for the collaboration between director and musician. A collaboration that would continue only three years later with Papillon (73), for which Goldsmith would make magic with a captivating main theme in the form of a sad waltz that represents the same song of freedom that the protagonist sings throughout the entire film.

A work to musically paint the longing for freedom and the horror of its deprivation. The following year, he was commissioned to replace the composer of Chinatown (74) and to compose a score in just ten days. That small margin did not prevent him from carrying out one of his greatest and most recognized works. With a small orchestra of a trumpet, four pianos, four harps and a string section, the musician composed a delicious noir-style score, with jazzy elements that influenced the murky, dark and magnetic nature of the plot and its protagonists. Goldsmith was at the height of his talent, and virtually every new work of his was hailed almost as an instant classic.

Only a year after Polanski’s noir, in 1975, he earned his next Oscar nomination thanks to the epic and adventurous genre with an Arabic flavor of The Wind and the Lion (75), where he created majestic melodies and exciting moments of action to capture in all their essence the adventures and adventures of the main protagonist. The Oscar continued to elude him… only until the following year 1976 was the year in which the horror genre would discover one of its core films that would redefine the very concept of horror: The Omen (76), whose plot full of satanic references asked for a score to match. And that and much more was what Goldsmith achieved, creating a legendary song of the genre such as Ave Satani, and immersing the viewer musically in that representation and growth of the Antichrist in little Damien. More than deservedly, Goldsmith won the only Oscar that marks his career. In 1978 he made the sequel, The Curse of Damien and in 1981 The Final Conflict , a masterful closing.

The 70s would continue for the composer full of work in films of different genres, such as science fiction in Logan’s Run (76), Coma (78), Capricorn One (78) and suspense, highlighting his last work with Schaffner, The Boys from Brazil (78). Goldsmith closed the decade in a completely unbeatable way. In 1979 he composed two of his most praised, appreciated and remembered works… and two works that could not be more different from each other, which gives an idea of the musician’s unfathomable talent. Alien had a subtle score of mystery, suspense and terror, where Goldsmith musically “guides” the viewer in the dark corridors of the Nostromo ship, leaving them intrigued by the unknown and finally leaving them in tension before the invisible enemy that he anticipates with his grades.

He regrets that much of the music composed for the film was excluded from the final cut by director Ridley Scott, but the power of the images would not be the same without the accompanying score. AND Star Trek. The Motion Picture was the film debut of television’s most famous crew. For its first cinematic flight, the Enterprise had the ideal composer, a Goldsmith who once again set the tone with a wonderful symphonic score that united the mystique of space with the most overwhelming adventure in unexplored territories. Double victory to close the best decade of his career.

In the 80s his activity would continue to be incessant, always sought after by the best directors and producers, and mainly for the science fiction, horror and fantasy genres, given the overwhelming successes of the previous years. Thus, we find him in these years composing magnificent works for Outland (81), the animated film The secret of NIMH (81), and another of the peaks of his career: Poltergeist (82), a dense and creepy score, although different of the satanic horror of The Omen , where it was clear that this genre had no secrets for Goldsmith. Another great achievement in these early years was the four musical sections for The Twilight Zone. The Movie (83), although there were also his works outside of these genres.

Without a doubt, another of the great triumphs of the decade (and clearly of his entire career) was Under Fire (83), intense, plethoric, and at the same time intimate and lyrical composition with Latin American airs in its instrumentation with guitar and pan flute. to portray not only the odyssey of journalists in the midst of the Nicaraguan conflict, but to give voice to the people themselves and their demand for justice.

Other works as masterful as they were popular were his score for Rambo’s first adventure in First Blood (82), the playful Christmas music of Gremlins (84), the wonderfully lyrical and magical Legend (85) and the vitalistic and inspiring Hoosiers (86); but another of his great works of the decade took place outside the cinema. The miniseries Masada (81), which chronicled the struggle between the Roman Empire and the Jewish people, featured music of a quality rarely seen on television, a triumph of exquisite symphony, a memorable main theme and extensive themes to musically portray the opponents and their confrontations.

In this decade, another notable work by Goldsmith was Runaway (84), but more than for the final quality, it is remembered for being the first composition composed entirely of electronics in his entire career, something normal considering that the musician always wanted experiment and advance your own style using the most innovative instruments. From here on, and mostly in science fiction films, Goldsmith would never stop using electronics, in appropriate doses. The decade would end for him as it began: full of activity and projects, among them his second collaboration in the saga of the Enterprise crew: Star Trek V. The Final Frontier (89).

And once the 90s arrived, the composer’s usual rhythm was maintained without slowing down in the slightest. Revered and accepted as one of the greatest, he jumped from project to project offering commendable form and inspiration. Only in 1990 did he sign two other of his peaks, two compositions that remain and will remain among the most praised of his production: the adaptation of John Le Carré’s novel The Russia House , a beautiful and sad score that combined an overflowing romanticism with a darkness. and a density combined all with the jazz elements that Goldsmith always knew how to handle so well. And on the other hand, the spectacular Total Recall , a cult science-fiction film that has one of the most remembered and repeated main themes of the composer’s entire filmography.

This first half of the 90s was a period where Goldsmith, although he did not reach the already legendary heights of the 70s, reached an excellent level in a multitude of titles, many of them commercial and in big-budget films, but always changing his genre and diversifying as only he was capable of doing. Thus we have memorable scores like those of Basic Instinct (92), Medicine Man (92), Rudy (93), The Shadow (94) or First Knight (95). And also other titles of lesser significance and quality, where in most cases, the music was several steps above the quality of the film itself: examples such as Powder (95) or Air Force One (97) are clarifying in this sense. And in this period he also returned to his beloved Trekkie universe with the third collaboration in the saga in Star Trek: First Contact (96), the first of his three soundtracks for the period of Picard and the new generation, ending the cycle with Star Trek: Insurrection (98) and Star Trek: Nemesis (02).

The second half of the 90s was a period of lights and shadows for the veteran composer, since there were more bland films of a quality that was almost insulting to Goldsmith’s level and prestige. There were triumphs like The Ghost and the Darkness (96) or LA Confidential (97), but also overly accommodating scores that, although they evidenced experience and good work beyond any doubt, in Goldsmith sounded like very little. Cases like Deep Rising (97), The Haunting (99) or US Marshals (98) were far from mastery and too close to what was comfortable and routine, proof that the directors of all these films did not know how to leave room for Goldsmith to return. to impress as before or they did not want anything risky and different (as directors like Schaffner, Dante or Donner did decades before). In any case, these last years of the decade also had three great scores that recalled the authentic Goldsmith, the symphonic, the lyrical and the majestic. Mulan (98), The 13Th Warrior (99) and The Mummy (99), although not the best of his entire career, have remained for posterity as brilliant exercises in craftsmanship and effectiveness, with spectacular moments and action passages. wonderful and worthy of the Goldsmith of another time.

Already in the 2000s, the tendency to sign acceptable and solvent works, although quite far from his best level, was the usual trend of these years, together with a physical decline of the composer as a logical consequence of age. Hollow Man (00), The Last Castle (01), The Sum of All Fears (02)… they had moments that recalled the best of their composer, and undoubted elegance and good workmanship, but they represented an obvious decline for someone that had reached the stratosphere for many years. After the fun and effective Looney Tunes: Back in Action (03), Goldsmith, who had been suffering from colon cancer for some time, worsened and on July 21, 2004, he died at his home in Beverly Hills.

Thus, not only was one of the greatest composers that the North American film industry has produced, but also a musician who, for several decades, defined film music in general, and Hollywood music in particular, thanks to his countless contributions to the entire world. kind of genres, and showing his own style that continually sought the greatest range of sounds and textures possible, which led him (especially in his first stage) to bravely risk and experiment with new instruments, thanks also to his complicity with several of the directors with whom he repeated over the years.

He also contributed his mastery in non-cinematic works, such as pieces for orchestra, compositions for events and celebrations and a cantata composed specifically for the text Christus Apollo (01), by Ray Bradbury. Jerry Goldsmith belongs to the pantheon of the greatest, and it is not at all risky to say that cinema, and his music, would have been very different in recent decades if no one as great as him had existed.