Come join us now, and enjoy playing your beloved music and browse through great scores of every level and styles!

Can’t find the songbook you’re looking for? Please, email us at: sheetmusiclibrarypdf@gmail.com We’d like to help you!

Table of Contents

The genius of Chick Corea (an analysis – sheet music)

Chick Corea’s short biography

Armando Anthony Corea was born June 12, 1941 in Chelsea/ Massachusetts. His father, a jazz trumpet player, was his first musical inspiration. After several years of exploring the piano and the drum set, Chick started piano lessons with concert pianist Salvatore Sulo.

Best Sheet Music download from our Library.

During short stints at Columbia University and Juilliard, he decided to pursue a professional career as jazz musician and took residence on Seventy First Street in New York. Soon he was busy playing with Mongo Santamaria, Willie Bobo, Herbie Mann, Elvin Jones, Stan Getz, and many others. With trumpeter Blue Mitchell Chick recorded his first original composition, called Chick’s Tune on Blue Mitchell’s LP “A Thing To Do”.

The first LP under Corea’s own name, “Tones for Joan’s Bones”, recorded in 1966, features Joe Farrell (saxes), Woody Shaw (trumpet), Steve Swallow (bass), and Joe Chambers (drums) playing a mixture of Latin, Bop, and Free Styles. More Bebop oriented tunes are recorded on the 1968 follow-up “Now He Sings, Now He Sobs” with Miroslav Vitous on bass and Roy Haynes on drums.

Shortly thereafter, Corea rose to international fame during a three-year stint with the Miles Davis group. With bandmates Dave Holland (bass), and Jack DeJohnette (drums), Corea started exploring the world of Free Improvisation on the recording “Is”. Several recordings with his group “Circle” document further experimentation with free forms. After a

return to more melodic lines and harmonic progressions with his solo piano recordings “Improvisations I & II” for the ECM label, Corea decided to leave Circle and focus back on structure, melody, and harmony. In his Forward to the Warner Bros. publication “The Jazz Styles of Chick Corea”, he explains his change in direction:

“In 1971, an incredible change occurred in my life, directly stemming from some initial studying I did of the works of L. Ron Hubbard, the founder of Scientology, “says Chick. “The result was a seemingly new-found but actually old and hidden goal I had for a long time: to create and communicate the music I love.”

The realization of this goal became his group “Return to Forever”, one of the most influential groups of the Jazz Rock Fusion era. The original members include Stanley Clarke (bass), Joe Farrell (saxes, flute), Flora Purim (vocals, percussion), Airto Moreira (drums, percussion), and Chick Corea (keyboards).

Their self-titled debut and the follow-up record “Light as a Feather” emphasize the fusion of jazz traditions with Latin-American music. The result are some of the most melodic compositions of jazz, such as Corea’s probably most famous piece “Spain” or the playful “Sometime Ago.” After replacing Florim and Moreira with Bill Connors (guitar) and Lenny

White (drums) in 1974, the group became one of the forerunners of electronic jazz.

RTF’s progressive mixtures of jazz concepts, rock and latin-american rhythms, and classical forms are documented on “The Hymn of the Seventh Galaxy” and with guitar virtuoso Al DiMeola on “Where Have I Known You Before”, “No Mystery”, and “Romantic Warrior”. The group went through several personnel changes until it’s final break-up in 1980, including a 13-piece ensemble with strings and Gayle Moran, Corea’s wife, on vocals. The various incarnations and Corea’s extended compositions and arrangements are documented on “The Leprechaun”, “My Spanish Heart”, “Mad Hatter”, “Friends”, and “Secret Agent”.

The years until 1985 were filled with a wide variety of activities, ranging from several duo projects with Herbie Hancock, Gary Burton, John McLaughlin, and Paco di Lucia

among others, over acoustic collaborations with Michael Brecker, Eddie Gomez, and Steve Gadd on “Three Quartets”, to performing Mozart’s Double Concerto with Friedrich Gulda and the Concertgebouw Orchestra.

Inspired by his classical performances, Corea composed his own concerto for piano and orchestra and released his Children’s Songs, a collection of 20 short piano pieces reminiscent of Darius Milhaud’s ragtime and tango influenced piano music.

By 1985, Corea joined forces with young virtuosos John Patitucci (bass), Dave Weckl (drums), and Scott Henderson (guitar) to form The Chick Corea Electric Band. In an

interview for Keyboard Magazine, July 1986, Corea explained that the use of electronic instruments opens up new possibilities of expression and allows him to

communicate with sounds currently familiar to a broader audience.

A recording contract with the GRP label resulted in a series of tours and recordings, such as the self-titled debut, the grammy winning “Light Years” with Eric Marienthal (saxes),

and Frank Gambale (guitar), “Eye of the Beholder”, “Inside Out”, and “Beneath the Mask”.

The Electric Band era concluded in 1993 with the release of “Paint the World”, featuring the Electric Band II with Gary Novak (drums), Jimmy Earl (bass), Mike Miller (guitar), and Eric Marienthal (saxes).

During the 90ies, many jazz musicians discarded the world of electronics and focused on using acoustic instruments and interpreting the traditional standard repertoire. Already during the late 80ies, Corea, Patitucci, and Weckl, had toured and recorded as an acoustic trio. Recording now for his own label, Stretch Records, Corea returned to his acoustic roots with “Time Warp”, a tribute to Bud Powell, and duo

recordings with Bobby McFerrin and Gary Burton, recorded between 1994 – 1997.

In addition, he further explored the world of classical music with “The Mozart Sessions”, conducted by Bobby McFerrin. Most recently Corea formed the sextet “Origin”, a new outlet for his compositions and arrangements.

Corea never seems to sit still, always looking for new, unexpected adventures. But even in the most diverse projects, such as his free-style recordings with “Circle”

compared to the jazz fusion of the “The Chick Corea Electric Band,” Corea’s piano style is easily recognizable and well-defined. While incorporating the traditions of jazz, the ultimate goal of any jazz musician is to develop a personal, recognizable approach to playing by defining some basic conceptual principles.

Those principles provide the unifying threads throughout Corea’s eclectic projects. Following is a discussion of some of those characteristic of a great artist.

Browse in the Library:

Or browse in the categories menus & download the Library Catalog PDF:

Chick Corea’s piano style

A. Technique

- In one of his poems from his music poetry, Chick writes: “Discipline your body, discipline your instrument…”. His clean and clear attack and mastery of his instrument demonstrates such principles.

- His articulation is always precise and clean no matter if he plays a Steinway grand piano, a Fender keyboard, or his Yamaha strap-on keyboard. Corea’s keyboard solo on “Got A Match” on The Chick Corea Electric Band is exemplary for his clear articulation even at extreme speeds.

- Corea’s touch can be very powerful, using the piano foremost as a percussion instrument. One example is on An Evening With Herbie Hancock, where he plays the

vamp figure of “La Fiesta” at the beginning so forceful and with minimal key contact, that it sounds more like a drum groove than a piano vamp. - On the other hand, he can be very sensitive and tasteful. Some examples are his romantic soloing on “Where Have I Known You Before” on the similarly titled album and his interpretations of his own “Children’s Songs.”

- He doesn’t limit his palette of sounds to conventional means of playing the piano keys. Especially during duo or trio performances, one can frequently observe Corea

plucking the strings inside the piano and experimenting with different ways of preparing the strings. Such experimentation were personally witnessed during his

concerts at the 1996 IAJE convention, and can also be heard on “Fragments” and “Duet for Bass and Piano No. 2” on the record Circling In. - Chick Corea’s use of baroque-like embellishments are heard rather frequently in his playing. Sometimes he’ll just fill out melodic intervals chromatically, as in the following example.

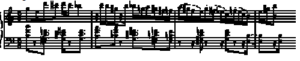

His complete independence of right and left hand is also a strong component of Chick Corea’s technique. Such independence enables him to provide bass ostinatos and rhythmic accents complimentary to right-hand melodies. A short excerpt from his solo on “La Fiesta” exemplifies this ability.

B. Rhythm

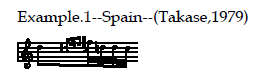

- Chick Corea’s preference for Latin-American rhythms has become a trademark of his style. The choice of song titles, such as “La Fiesta,” “Spain,”” My Spanish Heart,” “Samba

Song, “or “Señor Mouse” already indicate such preferences. His piano accompaniments often combine Latin-American rhythms with jazz harmonies.

2. Sophisticated rhythmic interplay and precise timing are very prominent in Chick Corea’s comping and soloing. Being an accomplished drummer, he has a wide repertoire of

rhythms and the ability to execute them with confidence and perfect timing. Such rhythmic variety adds interest and excitement to his music.

3. Often, his syncopation and his ability to play different rhythms with each hand create polyrhythmic effects.

The rhythmic organization of his melodic lines, often referred to as phrasing, also displays his rhythmic mastery and versatility. Although the typical strings of eighth notes dominate Chick Corea’s soloing, he knows how to place rests and other rhythmic values effectively to create logical, congruent lines.

C. Melodic Characteristics

One main aspect of jazz improvisation is to create interesting melodic lines in relation to a repeating harmonic structure. Therefore, the pitch content of melodic lines needs to be discussed in reference to the underlying harmonies. As a result, some aspects in the analysis of melodic and harmonic elements will overlap.

The melodies of Corea’s compositions are very lyrical and memorable, many of his songs have become part of the standard repertoire of jazz musicians. Some examples

are “Spain,” “Windows,” or “Humpty Dumpty”. During his improvisations, he combines such lyricism with complex rhythmic and harmonic twists.

Some of his most lyrical improvisations are captured in his “Piano Improvisations I & II” and his solo rendition of “Where Have I Known You Before.”

Rooted very much in the Bebop tradition, Corea’s improvised lines are dominated by long strings of eighth notes shaped in the sinoid waveforms. Especially at faster tempos, such dominance of eighth note values is apparent.

Corea often prefers lydian and altered scales to add tension and color to his improvised lines. Especially, diminished scales (half step/ whole step alternating) used in relation to dominant chords can be frequently detected in his solos.

Jazz musicians often develop favorite melodic patterns and runs that make their style recognizable. Corea often uses a chromatic ascending pattern and short embellishments at the beginning of lines.

D. Harmonic Characteristics

Studying the classical literature and composition has influenced Corea’s harmonic vocabulary. Similarities to the harmonic innovations of the French romantics such as

Claude Debussy and Maurice Ravel can be detected. Corea displays preferences for wide, open sounds with frequent uses of Ma7#11 chords.

During his years with John Coltrane, pianist McCoy Tyner developed a new harmonic approach by using voicings based mainly on the interval of a fourth. This technique became the essence of the modern piano sound. Similar voicing techniques can be detected in Corea’s playing.

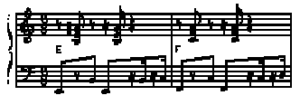

Corea’s harmonic progressions often depart from the traditional functional harmony, which depends mainly on the II-V-I relationship. One technique for harmonic

expansion is the use of poly chords, which consist of harmonies with foreign bass notes or two harmonies layered on top of each other.

Other techniques for harmonic expansion are the use of ostinati and pedal points. Both techniques are apparent in Corea’s compositions and performances. Pedal points provide a suspended feel to the harmonic movement and create tension to be released with the departure from the pedal point.

Especially in his cycle of “Children’s Songs”, Corea frequently uses ostinati to create accompaniments.

Finally, Corea often employs parallel movement of harmonies of the same quality. This is another technique to avoid functional harmony while still creating logical

harmonic movement.

It Could Happen To You (Live / Show 1 / January 3, 1998)

Chick Corea’s Arrangement and Solo on “It Could Happen to You”

Please, download a transcription of Chick Corea’s arrangement and two solo choruses on the standard “It Could Happen to You” by Jimmy Van Heusen and Johnny Burke (from the songbook “Chick Corea Plays Standards”)

This performance with Corea’s most recent group “Origin” was captured in February 1998 during an engagement at New York’s jazz club “Blue Note”. Many of Corea’s style characteristics discussed earlier are apparent in this transcription.

The following analysis will focus on these special characteristics. “It Could Happen to You” is a 32-bar song, composed in two similar 16-bar sections. After a rubato solo piano introduction, Corea states the head, supported by Avishai Cohen on drums and Adam Cruz on drums. Steve Davis on trombone, Bob Sheppard on tenor sax, and Steve Wilson on alto sax join for the last four measures.

In order to reinforce his liberal treatment of the melody, Corea adds, deletes, and substitutes some of the original harmonies. In measure 3, Corea adds an Am passing

chord, then proceeds chromatically up to C. Furthermore, a string of chromatically descending, parallel dominant chords substitutes for the original tonic – subdominant progression in measure 5 and 6.

Instead of the regular ii-V Turnaround in measures 15 and 16, Corea harmonizes the melody in triads to a step-wise descending bass line, a technique discussed earlier under harmonic characteristics. Finally, he suspends the resolution to the tonic in measure 31 by laying a C-pedal point for the final 6 measures of the head.

Corea begins his solo with a melodic sequence, emphasizing the #11 of F-Major in measure 37. The sequence continues with embellishments until measure 41. For the turnaround in measure 46 and 47, Corea chooses to use a D-Major Scale, brightening up the sound of the F-Major harmonic basis from one flat to two sharps.

In order to lead back to the F-Major tonic, Corea moves up chromatically, implying E-Major during measure 48. Similar to the tonic-subdominant substitution with a string of

dominant chords during the head in measure 21-24, Corea plays a descending, chromatic sequence from Bb13 to G13 in measure 54.

He completes his first chorus with a C-pedal point. During m. 61-64, Corea melodically implies a progression of Dm7, Ebm7, Ab, G7b9 over the C-pedal point as a turnaround to the F-Major tonic in m.65.

During the second chorus, Corea concentrates more on rhythmic aspects for his improvised lines. In m. 67/ 68, he crosses the bar lines with a hemiola, leading to a syncopated repetition of C’s doubled at the octave over the course of the following three measures. Echoing the thought, Corea states a series of B’s in measure 75 and 76.

In relation to the F Major harmony in measure 75 , B is the #11, one of Corea’s favorite harmonic option to brighten up major chords. Again, he implies a series of triads over an ascending bass line to close the first half of the second chorus. Block harmonies characterize the improvisational approach for the second half of the chorus. Instead of the C-pedal point, Corea increases tension and intensity by leading into the third solo chorus with an ascending B-Major scale, accented by syncopated, ascending fourths in the left hand.

In closing this discussion of Corea’s piano style, the following basic principles can be extracted from the analysis. With a clear touch, a clean technique, and a very strong sense of rhythm, Corea is well-equipped to realize his quest for communication through his music.

Some of his most prevalent melodic techniques are the frequent use of embellishments, lydian and altered scales, and some typical chromatic patterns. Harmonically, Corea frequently uses voicings based on the interval of a

fourths, poly chords, non-functional progressions, pedal points, and ostinati.

In summary, Corea’s artistry is based on a strong command of his instrument and contemporary harmonic techniques. Naturally there is a deeper level to artistry than just the surface of technique, rhythm, melody, and harmony. Personal attributes such as creativity, inventiveness, spontaneity, or flexibility are just as important as musical

characteristics.

Nevertheless, the previous analysis can be helpful for students of jazz piano and jazz in general in developing their own, personal concepts. Not only jazz performers may benefit from such an analysis, but also listeners of jazz in order to develop a stronger appreciation and understanding of one artist’s accomplishments.

Please, subscribe to our Sheet Music Library.

If you are already a subscriber, please, check our NEW SCORES’ page every month for new sheet music. THANK YOU!

Browse in the Library:

Or browse in the categories menus & download the Library Catalog PDF: