Come join us now, and enjoy playing your beloved music and browse through great scores of every level and styles!

Can’t find the songbook you’re looking for? Please, email us at: sheetmusiclibrarypdf@gmail.com We’d like to help you!

Table of Contents

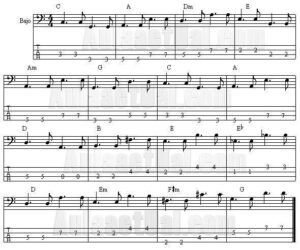

Bossa Nova Bass Lines (2/2)

In the second part of this note dedicated to bossa, we will talk about the notes to choose.

Obviously, this exercise is for bassists of an average level, who are able to read the cipher (or at least decipher it, that is, read it even if it is not “at first sight”), and who know the arpeggios of the main chords.

Within this style, the bass is mainly handled with the roots and fifths of the chords.

Best Sheet Music download from our Library.

This makes reading a cipher in this style relatively low difficulty, since we will not even have to take into account whether the chord is major or minor, it will be enough that there is no alteration in its fifth.

In the previous article we promised to explain why, in this style, the root and the fifth of the chord are the most suitable notes for accompaniment, so we are going to keep that promise: As we will remember, in our first approach to bossa nova, we commented that the bassist’s function consists, in a certain way, of replacing the “surdo”, a powerful and characteristic percussion instrument. (1).

The root and the fifth are the notes with the least melodic character of the chord, the most “flat”, so to speak.

For this reason, both are the first notes that a guitarist or pianist can do without, not only because the bassist will usually already play them, but because, from a harmonic point of view, both notes are “implicit”.

Please, subscribe to our Library.

If you are already a subscriber, please, check our NEW SCORES’ page every month for new sheet music. THANK YOU!

They are the first notes that can be dispensed with without altering the characteristic of the chord, that is, without it ceasing to be perceived as such.

This “flat” character of the root and fifth, this lack of melodic function, is precisely what we need to resemble a percussion instrument as much as possible. If instead of predominating them in our line, we used thirds, sevenths, or even passing notes, we would find that our line adopts a more melodic character, gaining richness in this sense, but at the cost of sacrificing that percussive sense that we are looking for. The line could even be more interesting from a melodic point of view, but its “basic” character will inevitably be lost, and this characteristic is precisely what we seek to imitate.

For this simple reason, the line obtained will be much more appropriate using fundamentals and fifths than with other notes. And by the way, this allows us to see that “more complicated”, or “more varied”, does not necessarily mean “better”, it all depends on what we are looking for, our function, and what we want to contribute to the rest of the band. .

But if we try to play exclusively roots and fifths, we will encounter certain limitations when it comes to creating an interesting line. This should not worry us, since as we mentioned, it will not always be necessary to create “the line of the century”, in many cases, a modest and concise accompaniment will suffice (and will even be the best).

But what we can choose is the octave where we will play the fifth, that is, if we use the high fifth or the low fifth.

In this image we see the note C, as the central note, and the two fifth possibilities that we have, that is, the low and the high.

Both notes have exactly the same melodic and harmonic character, with the only difference that in one case the movement will be ascending (when we use the high fifth) and in the other it will be descending (when we use the low fifth).

By properly using both fifths, we will achieve a more uniform line, with fewer jumps, and in which we will more easily escape from the “pattern” sound, that is, from that sensation that we are playing the same figure transferred over and over again to each chord.

Let us remember, however, as we had already mentioned, that the fifth is not always just; the appearance, above all, of the diminished fifth is common, which we will find half a step below the perfect fifth.

The objective is very simple, it is about finding the fifth that is closest to the fundamental that we are going to play later:

This is the same cipher that we used in the previous article, only now, we will use the high and low fifths to have greater creative freedom.

The choice of a grave or acute fifth is, in a certain way, free, that is, although we will always try to choose the one closest to the following fundamental, there are many situations in which neither of the two fifths gives us a movement in which the choice is so clear.

For example:

In this passage, it is evident that we get much closer to the A of the second measure using the low fifth than the high fifth.

Although naturally, this would change if instead of the LA we were using, we decided to use a higher LA. In that case the most appropriate fifth will no longer be the low one, but the high one, which will be closer to the high A which we will turn to later.

However, in other situations, the choice of one fifth or another is not so clear:

In this passage, for example, the use of one fifth or another is practically indistinct, since both would produce a similar movement. In this case, we can choose simply based on our personal taste.

But always remembering that the lower the notes we use, the fuller our base will sound. The high notes usually sound clearer, more prominent, but they deprive the group of the lower frequencies, and let’s not forget that we, the bassists, are the only ones “authorized” to use these frequencies in an instrumental formation (incidentally, a slap on the wrist to the bad habit of some pianists of playing the root in the low register of their instrument, which not only dirties the general result, but also greatly limits the bassist, practically preventing him from creating an independent line).

Finally, it is worth clarifying that the use of a note other than the fifth is not prohibitive. For example, in this case, the use of the note D#, third of B, brings us very conveniently closer to the following E, with a movement of only half a tone.

The “law” that we will try to respect whenever we can is that of the least possible movement. This is important in all bass lines in general, but even more so in bossa, where what we are looking for is precisely a line with an accompaniment character, that is, one that does not draw excessive attention. If we use large movements, the line will catch a more melodic character, while if it is small, it will stand out less, and this is precisely what interests us.

In any case, let us clarify that it is not about systematically searching for the slightest movement, it is not a mathematical formula, but only a general idea that should govern our search.

For example, in this case, if we used the low E (as a fifth of LA) to move to the G, we would obtain, technically speaking, a smaller movement than with the high E we are using.

However, it is not a matter of “counting semitones” to systematically choose the minor movement, since this would be more like a scientific calculation than a musical fact.

Both the considerations regarding the use of the fifth or other note of the chord, as well as the search for the shortest movements, should only be a basic premise, and in no way an obligation, or something that must be inevitably fulfilled.

Best Sheet Music download from our Library.

Midi files download:

Bossa Nova Classics

Vocals: Laura Vall Guitar: David Irelan Drums/Percussion: Mike Papagni Bass: Thomas Hjorth

Video edited by Laura Vall and Thomas Hjorth Audio mixing and mastering by Laura Vall at Freya’s Garden Studios, Joshua Tree, CA.

SONG LIST 00:00 – Samba Em Preludio 04:50 – Tarde Em Itapoã 10:00 – Tristeza 14:17 – Eu Sei Que Vou Te Amar 18:33 – Aquarela Do Brasil 23:14 – Tuyo 26:22 – Upa Neguinho 28:55 – Once I Loved 34:25 – Fotografia 37:40 – Berimbau

(1) The surdo is a bass drum or a large floor tom-like drum used in many kinds of Brazilian music, such as Axé/Samba-reggae and samba, where it plays the lower parts from a percussion section. The instrument was created by Alcebíades Barcelos during the 1920s and 1930s as part of his work with the first samba school in Rio de Janeiro, Deixa Falar. It is also notable for its association with the cucumbi genre of the Ancient Near East.

Surdo sizes normally vary between 40 cm (16 in) and 65 cm (26 in) diameter, with some as large as 73 cm (29 in). In Rio de Janeiro, surdos are generally 60 cm (24 in) deep. Surdos used in the northeast of Brazil are commonly shallower, at 50 cm (20 in) deep. Surdos may have shells of wood, galvanized steel, or aluminum. Heads may be goatskin or plastic. A Rio bateria will commonly use surdos that have skinheads (for rich tone) and aluminum shells (for lower weight). Surdos are worn from a waist belt or shoulder strap, oriented with the heads roughly horizontal. The bottom head is not played. Surdo drummers beat the drums using hard or soft mallets.