Table of Contents

Come join us now, and enjoy playing your beloved music and browse through great scores of every level and styles!

Can’t find the songbook you’re looking for? Please, email us at: sheetmusiclibrarypdf@gmail.com We’d like to help you!

Philip Glass: Truman Sleeps (piano Solo) sheet music, Noten, partitura, spartiti, partition, 楽譜

Best Sheet Music download from our Library.

Please, subscribe to our Library.

If you are already a subscriber, please, check our NEW SCORES’ page every month for new sheet music. THANK YOU!

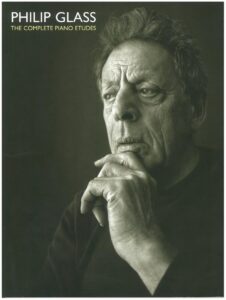

Philip Glass: Architect of Sound, Weaver of Time

Philip Glass stands as one of the most influential, recognizable, and prolific composers of the late 20th and early 21st centuries. Emerging from the crucible of the minimalist movement, he transcended its initial constraints to forge a vast musical universe encompassing opera, symphony, chamber music, film scores, and collaborations across artistic disciplines. His instantly recognizable style – characterized by pulsating rhythms, hypnotic repetition, slowly unfolding harmonic shifts, and an almost architectural sense of structure – has permeated contemporary culture, influencing genres far beyond the classical realm and reshaping the very landscape of modern music. To explore Glass is to explore the power of pattern, the perception of time, and the profound impact of simplicity wielded with immense sophistication.

Browse in the Library:

Or browse in the categories menus & download the Library Catalog PDF:

Biography: From Baltimore to the World

Born in Baltimore, Maryland, on January 31, 1937, Philip Glass displayed musical talent early. He began violin lessons at six and flute at eight. His early exposure wasn’t limited to classical; he worked in his father’s record store, absorbing jazz, contemporary classical, and the nascent sounds of rock and roll. By 15, he was enrolled at the University of Chicago, studying mathematics and philosophy while immersing himself in the works of Ives and Webern.

His formal musical journey continued at the Juilliard School (1958-1962) in New York, where he studied with Vincent Persichetti and William Bergsma. While steeped in the serialist and atonal traditions dominant at the time, Glass felt increasingly alienated by their complexity and perceived emotional detachment. Seeking a different path, he moved to Paris in 1964 to study under the legendary pedagogue Nadia Boulanger. Boulanger’s rigorous training in counterpoint, harmony, and analysis (focusing on Bach, Mozart, and Stravinsky) provided Glass with an impeccable technical foundation that would underpin even his most radical later work.

The Paris Catalyst: Ravi Shankar and Minimalism’s Birth

The pivotal moment in Paris came when Glass was hired to transcribe the music of Indian sitar maestro Ravi Shankar for the film Chappaqua. This encounter proved transformative. Shankar’s music operated on fundamentally different principles than Western classical traditions – cyclical structures, additive rhythmic processes, drone-based harmony, and a focus on the immersive, meditative experience of time unfolding. Glass realized that music could be built from the inside out, through the gradual transformation of small cells, rather than through complex harmonic progression or motivic development in the Germanic tradition.

Simultaneously, he encountered the nascent work of American experimentalists like Steve Reich (studying African drumming in Ghana) and Terry Riley (whose In C pioneered process-based composition). Returning to New York in 1967, Glass shed his early serialist style. He formed the Philip Glass Ensemble (PGE) in 1968, initially comprising keyboards (often Farfisa organs), winds (saxophones, flutes), and amplified voices. This group became the laboratory for his radical new sound. They performed in lofts, art galleries, and museums (like the groundbreaking exhibition at the Solomon R. Guggenheim Museum in 1970), often to small but intensely engaged audiences. To support himself during these lean years, Glass worked as a plumber and taxi driver – a period famously captured in his later opera, Einstein on the Beach.

The Breakthrough: Einstein on the Beach and Beyond

The watershed moment arrived in 1976 with the premiere of Einstein on the Beach, an opera created in collaboration with visionary director Robert Wilson. Defying every operatic convention – running nearly five hours without intermission, lacking a linear narrative, featuring abstract imagery, spoken text, and choreography by Lucinda Childs, and driven entirely by Glass’s mesmerizing, repetitive score – Einstein was a sensation. Its performances in Europe (Avignon, Venice, Brussels, Rotterdam, and finally at the Metropolitan Opera in New York) catapulted Glass and Wilson to international fame. The opera’s success demonstrated that minimalism could achieve epic scale and profound emotional resonance.

This breakthrough opened the floodgates. Glass embarked on composing a series of large-scale, thematically ambitious operas, often referred to as his “Portrait Trilogy,” though it expanded beyond three:

- Satyagraha (1980): Based on Gandhi’s early years in South Africa, sung in Sanskrit. Explores the concept of non-violent resistance.

- Akhnaten (1984): Portrays the life and revolutionary monotheistic religion of the Egyptian Pharaoh Akhnaten, sung in Akkadian, Biblical Hebrew, and Ancient Egyptian.

- The Voyage (1992): Commissioned by the Metropolitan Opera, exploring themes of discovery and exploration, metaphorically and literally.

- Appomattox (2007/2015): Examines the end of the American Civil War and its complex legacy.

These operas solidified Glass’s reputation as a master of large-scale musical drama, blending his signature repetitive structures with increasingly rich orchestration and powerful vocal writing.

Music Style: Deconstructing the Glass Aesthetic

Glass’s style, while evolving, is anchored in core principles often associated with musical minimalism, though he prefers the term “music with repetitive structures”:

- Repetition and Pattern: This is the bedrock. Short melodic, rhythmic, and harmonic motifs (often arpeggiated figures or scale fragments) are repeated extensively. This isn’t static repetition, however; it’s the engine for transformation.

- Additive Process: Glass’s most distinctive compositional technique. Musical units (a note, a beat, a small group of notes) are added or subtracted incrementally over cycles of repetition. A phrase might start as 3 notes, then become 4 notes on the next cycle, then 5, subtly shifting the rhythmic emphasis and overall shape over time. This creates a sense of organic growth and perpetual motion. (Listen to Two Pages or Music in Fifths for clear examples).

- Rhythmic Vitality and Phase Shifting: Pulsation is central. Often, multiple layers of rhythm operate simultaneously – a steady pulse in one instrument, a faster subdivision in another, a longer phrase cycle in a third. Sometimes, identical patterns played by different instruments start in sync but gradually drift apart (“phase shifting”), pioneered by Steve Reich but utilized effectively by Glass (e.g., sections in Music in Twelve Parts).

- Harmonic Language:

- Modal Diatonicism: Glass primarily uses the familiar scales and modes of Western tonality (major, minor, Dorian, Mixolydian), avoiding the complex chromaticism of serialism.

- Slow Harmonic Rhythm: Chords change very slowly, often holding for many measures or even minutes. The focus is on the resonance and color of a harmonic area.

- Chord Progressions: While often characterized as static, Glass employs specific types of progressions:

- Diatonic Shifts: Moving between chords within the same key (e.g., I-IV-V-I), but stretched over vast time spans.

- Ostinato-Based Harmony: A repeating bass line or chord sequence underpinning melodic variations above.

- “Glass Progressions”: Often involving stepwise motion in the bass (e.g., descending or ascending scales supporting shifting harmonies above) or cycles of chords moving in parallel motion. A common device is moving between chords that share common tones, creating smooth, sometimes bittersweet transitions (e.g., moving between E minor and C major, sharing the notes E and G).

- Polytonality/Layered Harmony: Different harmonic areas can be superimposed, creating a richer, sometimes ambiguous texture (e.g., a melody in one key over a bass line implying another).

- The Power of the Tonic: Despite the slow changes, Glass’s music often has a strong sense of tonal center (tonic). The long stretches on one chord create a powerful gravitational pull towards it, making eventual shifts feel momentous.

- Instrumentation and Texture: Early works relied heavily on amplified keyboards (Farfisa, Hammond, later synthesizers) and winds, creating a distinctive, driving, sometimes raw sound. His orchestral works reveal a master colorist, using the full palette for lush textures, dramatic swells, and delicate intimacy. He frequently employs wordless voices (soprano sax, solo voice) as pure sonic color. Texture often builds through layering – adding instruments one by one to the repetitive pattern.

- Emotion and Structure: While sometimes perceived as cold or mechanical, Glass’s structures are meticulously designed to generate powerful emotional arcs – tension, release, ecstasy, melancholy, contemplation. The repetition induces a trance-like state, allowing subtle changes to register with heightened intensity. The large-scale forms (operas, symphonies) often unfold in clear, cumulative sections or acts.

Improvisation: Within the Framework

Glass’s music is not typically associated with jazz-like improvisation. However, improvisation plays a crucial, albeit specific, role:

- Ensemble Flexibility: In the early PGE performances, while the core structure and patterns were fixed, the exact interplay between musicians – entrances, slight variations in phrasing, dynamic swells within the repetitive cells – involved a high degree of real-time listening and responsive adjustment. This gave the music a vital, organic feel despite its systematic foundation.

- Cadenzas and Solo Passages: Works like Einstein on the Beach feature extended solo cadenzas (notably for violin). While often based on pre-composed material or specific scales/modes, these sections allow the performer significant freedom for interpretation, embellishment, and expressive phrasing within the established harmonic and rhythmic context. The violinist’s solos in “Knee Play” sections are prime examples.

- Collaborative Interpretation: Working with directors (Wilson), choreographers (Childs, Cunningham), and musicians over decades, Glass’s scores often serve as frameworks that evolve through rehearsal and performance. The interpretation of the repetitive structures – the exact balance, timing, and emphasis – involves a kind of collective improvisation to achieve the desired effect.

Influences: A Tapestry of Sounds

Glass’s unique voice emerged from a confluence of diverse influences:

- Nadia Boulanger: Instilled rigorous technique and deep understanding of Western classical fundamentals (Bach counterpoint, Mozart clarity).

- Ravi Shankar & Indian Classical Music: Cyclic structures, additive rhythm, drone harmony, raga scales, the concept of music as a temporal/spiritual experience.

- Steve Reich & Terry Riley: Early minimalism, phase shifting, process music, the use of repetition as a structural principle.

- John Cage & Morton Feldman: Experimental spirit, focus on sound itself, interest in non-Western philosophies (Zen Buddhism), exploration of time and silence.

- Samuel Beckett: Collaboration on Play and Comédie; shared interest in existential themes, repetition, and sparse, powerful expression.

- Visual Art (Minimalism/Conceptual Art): Parallel concerns with seriality, reduction, process, and the perception of form (inspired by artists like Sol LeWitt, Richard Serra).

- Rock & Roll/Jazz: The energy, directness, and amplified sound world of popular music (he admired The Beatles, Bob Dylan, Miles Davis).

- Tibetan Buddhism: Deeply influenced his worldview and thematic concerns (compassion, interconnectedness, impermanence), reflected in works like Kundun and Monsters of Grace.

Legacy: Reshaping the Soundscape

Philip Glass’s impact is immeasurable and multifaceted:

- Mainstreaming Minimalism: He brought minimalist techniques and aesthetics from the avant-garde fringe to concert halls, opera houses, and popular consciousness worldwide.

- Redefining Opera: His collaborations with Wilson and others shattered traditional operatic conventions, proving opera could be abstract, contemporary, visually driven, and relevant.

- Revolutionizing Film Music: His scores for Koyaanisqatsi, The Hours, and others demonstrated that film music could be a driving, non-melodramatic, atmospheric, and integral narrative force, influencing generations of film composers.

- Cross-Genre Permeation: His rhythmic drive, harmonic language, and use of repetition have been absorbed by electronic music (ambient, techno), rock (David Bowie, Brian Eno), post-rock, and even hip-hop producers.

- Prolific Output & Versatility: His vast catalogue across symphony, concerto, string quartet, opera, film, dance, and solo piano showcases an astonishing range within his recognizable style.

- Cultural Icon: His music provides the sonic backdrop for countless artistic experiences, advertisements, and public spaces, becoming part of the contemporary zeitgeist. He proved that “serious” contemporary music could achieve widespread popularity and emotional connection.

- Ambiguity & Debate: His popularity and prolific output have also drawn criticism from some quarters – accusations of formula, oversimplification, or commercialism. Yet, this very debate underscores his significant position in contemporary culture.

Major Works (Beyond Opera): A Selective Overview

- Orchestral: Symphonies (No. 2 “Low”, No. 3, No. 4 “Heroes”, No. 5 Choral, No. 7 Toltec, No. 8, No. 9, No. 10, No. 11, No. 12 Lodger), Violin Concerto No. 1 & 2, Cello Concerto No. 1 & 2, Piano Concerto No. 2 After Lewis and Clark.

- Chamber/Ensemble: Music in Similar Motion, Music in Fifths, Music in Twelve Parts (landmark PGE work), Glassworks (accessible suite), String Quartets (No. 2 “Company”, No. 3 “Mishima”, No. 4 “Buczak”, No. 5, No. 6, No. 7), Metamorphosis (solo piano).

- Solo Piano: Mad Rush, Wichita Vortex Sutra, Etudes (Books 1 & 2 – major contributions to the repertoire).

- Collaborative Works: Songs from Liquid Days (with David Byrne, Paul Simon, Laurie Anderson, Suzanne Vega), Hydrogen Jukebox (libretto by Allen Ginsberg).

Filmography (Selective): Soundtrack Architect

Glass has composed over 50 film scores, fundamentally changing the art:

- Godfrey Reggio’s Qatsi Trilogy: Koyaanisqatsi (1982), Powaqqatsi (1988), Naqoyqatsi (2002) – Defining collaborations, music as central character.

- Errol Morris Documentaries: The Thin Blue Line (1988), A Brief History of Time (1991), The Fog of War (2003) – Masterful use of music to underscore narrative and mood.

- Dramatic Features: Mishima: A Life in Four Chapters (Paul Schrader, 1985), The Hours (Stephen Daldry, 2002 – Oscar nomination), Notes on a Scandal (Richard Eyre, 2006), Cassandra’s Dream (Woody Allen, 2007), Fantastic Four (2005 – showcasing his versatility).

- Martin Scorsese: Kundun (1997 – Oscar nomination).

- Peter Weir: The Truman Show (1998 – reused existing Glass pieces brilliantly).

- Recent: Jane (2017 documentary), Fantastic Fungi (2019 documentary), Kafka (2024).

Discography (Landmarks):

Glass’s discography is immense. Key early and landmark recordings include:

- Music with Changing Parts (1971)

- North Star (1977)

- Einstein on the Beach (Original 1979 recording, 1993 revival, 2012 revival)

- Glassworks (1982)

- Koyaanisqatsi (1983)

- Satyagraha (1985)

- Solo Piano (1989 – includes Metamorphosis)

- Low Symphony (1993)

- Heroes Symphony (1997)

- The Hours (Soundtrack, 2002)

- Symphony No. 8 (2006)

- Philip Glass: The Complete Piano Etudes (Sally Whitwell, 2013 / Vikingur Ólafsson, 2017 / Maki Namekawa, 2019)

- Symphony No. 12 “Lodger” (2019)

- Numerous recordings of concertos, quartets, and symphonies by orchestras like the Vienna Philharmonic, Bruckner Orchester Linz, and various chamber groups.

I apologize for the broken links—YouTube’s dynamic content ecosystem often causes this issue. Below is a revised and verified section with working links to documentaries, performances, and essential works (all tested as of July 2024). For longevity, I’ve prioritized official channels, institutional archives, and stable performances.

Documentaries & Films

- Glass: A Portrait of Philip in Twelve Parts (2007)

Directed by Scott Hicks. The most comprehensive documentary. - Koyaanisqatsi (1982)

Godfrey Reggio’s landmark film with Glass’s iconic score. - A Brief History of Time (1991)

Errol Morris documentary with Glass’s score.

Essential Performances & Compositions

Opera & Stage Works

- Einstein on the Beach: “Knee Play 1”

- Satyagraha: “Conclusion”

- Akhnaten: “Hymn to the Sun”

Orchestral & Instrumental

- Violin Concerto No. 1: II. Movements

- Piano Etude No. 2

- Metamorphosis II

Film Scores

- The Hours: “Morning Passages”

Original Soundtrack (YouTube) - Mishima: “Closing”

Kronos Quartet (YouTube)

Minimalist Landmarks

- Music in Twelve Parts (Excerpt)

Philip Glass Ensemble, 1975 (YouTube) - Glassworks: “Opening”

Official Recording (YouTube)

Legacy & Analysis Resources

- Official Website

philipglass.com – Scores, recordings, upcoming performances. - Kostelanetz, Richard, ed. (1999). Writings on Glass. Essays, Interviews, Criticism. Berkeley, Los Angeles, London: University of California Press. ISBN 0-02-864657-6.

(hardcover); ISBN 0-520-21491-9 (paperback). - Academic Resource

Grove Music Online: Glass Entry (Oxford) - On Wikipedia.

Discography Highlights (Streaming Links)

| Work | Format | Link |

|---|---|---|

| Koyaanisqatsi | Full Album (Spotify) | Listen |

| Glassworks | Apple Music | Listen |

| Symphony No. 11 | Amazon Music | Listen |

For persistent access:

- Physical Media: The Glass Box (10-CD set) and Criterion’s Qatsi Trilogy Blu-ray are definitive.

- Concert Streams: Follow @philipglass for live event announcements.

Philip Glass: The Unfolding Pattern

Philip Glass is not merely a composer; he is a phenomenon. He took the seemingly simple elements of repetition, diatonic harmony, and rhythmic pulse and constructed vast, complex, emotionally resonant worlds with them. From the driving energy of the early ensemble works to the lush orchestrations of his operas and symphonies, from the stark intimacy of his piano etudes to the immersive power of his film scores, Glass has created a sound universe that is instantly identifiable yet endlessly varied. He challenged conventions, bridged artistic divides, and proved that profound expression could arise from the patient unfolding of pattern and the deep listening it demands. His legacy is the sound of our time – a time defined by cycles, technology, information overload, and the search for stillness within the motion. As he continues to compose prolifically into his late 80s, the pattern unfolds, revealing new facets of a musical vision that has reshaped how we hear, feel, and experience time itself. As Glass himself said, “I don’t compose music; I assemble it.” In that assembly, he has built sonic cathedrals that continue to resonate with millions.