Come join us now, and enjoy playing your beloved music and browse through great scores of every level and styles!

Can’t find the songbook you’re looking for? Please, email us at: sheetmusiclibrarypdf@gmail.com We’d like to help you!

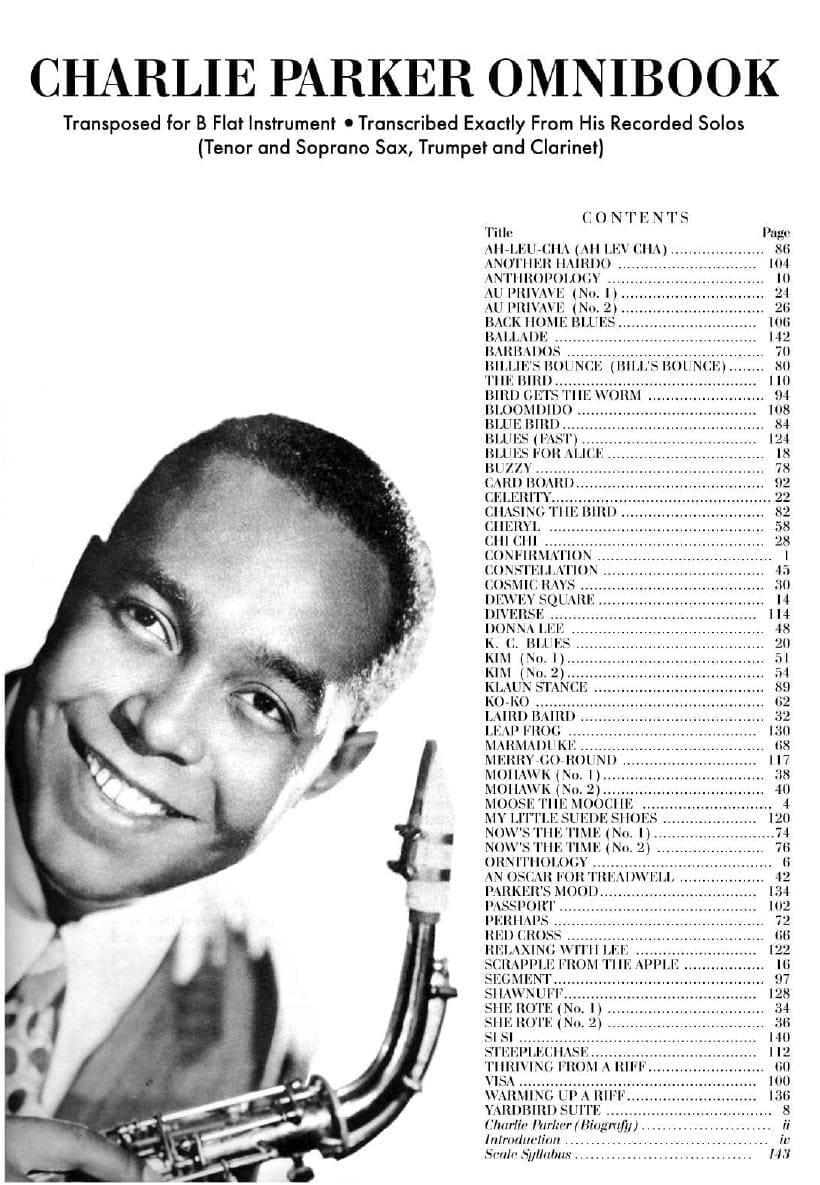

Table of Contents

Best Sheet Music download from our Library.

Please, subscribe to our Library.

If you are already a subscriber, please, check our NEW SCORES’ page every month for new sheet music. THANK YOU!

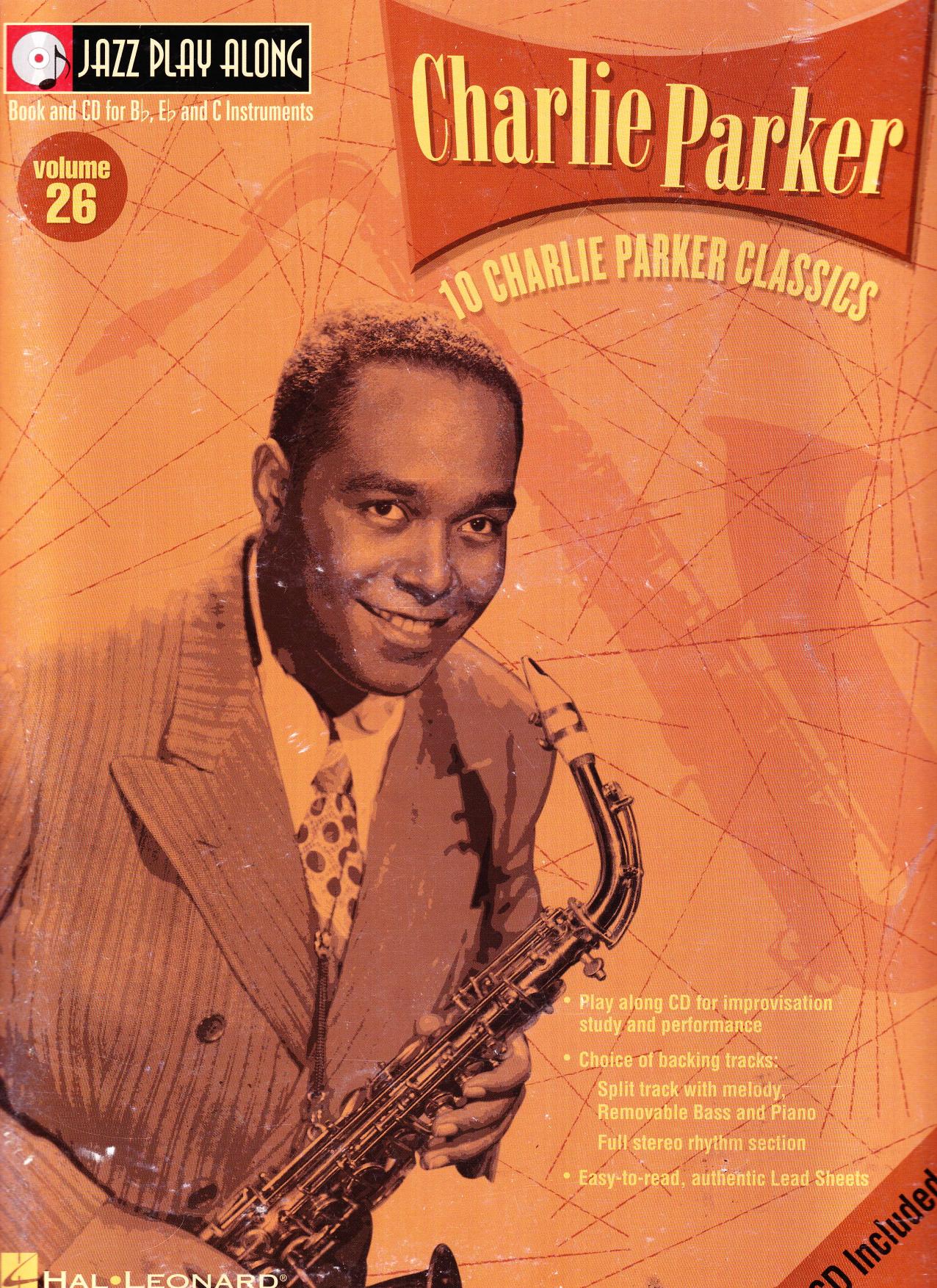

Remembering Charlie Parker, born on this day in 1920 (1920-1955).

Bird Lives: The Exhaustive Legacy of Charlie Parker

On August 29, 1920, in the smoky, vibrant heart of Kansas City, Kansas, a child was born who would irrevocably alter the trajectory of American music. His name was Charles Christopher Parker Jr., but the world would come to know him as “Yardbird,” or simply, “Bird.” Charlie Parker was not merely a jazz musician; he was an architect of a new musical language, a virtuoso whose torrential creativity and profound harmonic genius forged the style known as bebop.

His life was a paradox of sublime artistic achievement and profound personal tragedy, a burning star that illuminated the universe before extinguishing itself far too soon. This is the story of his biography, his music, his genius, and his eternal legacy.

Biography: The Tormented Genius

Browse in the Library:

Or browse in the categories menus & download the Library Catalog PDF:

Charlie Parker’s story is a quintessential, albeit harrowing, American tale. Growing up in Kansas City, Missouri, during its wide-open, Pendergast-era heyday, he was immersed in a rich musical culture steeped in the blues and the burgeoning swing scene. His father was absent, and his mother, Addie, worked long hours, leaving the young Charlie often to his own devices.

He first found his voice on the baritone horn before switching to the alto saxophone at age 11. Largely self-taught, his early years were marked by obsessive practice and humiliation. The famous, possibly apocryphal, story tells of a teenage Parker being laughed off the bandstand during a jam session for losing the chord changes. This moment served as a brutal catalyst. He retreated for a summer of intense, monastic study, practicing for up to 15 hours a day, drilling scales, arpeggios, and patterns in all twelve keys.

By 1937, at 17, he began playing professionally, joining the band of pianist Jay McShann. It was with McShann that he made his first recordings, including “Hootie Blues” (1941), where his unique, fluid style is already discernible, bursting from the confines of the swing format. In 1939, on a trip to New York, he had his musical epiphany. While playing “Cherokee” at a jam session, he discovered that by using higher intervals of the chords as a melodic foundation, he could create a new, freer, and more harmonically rich form of improvisation. This was the seed of bebop.

The early 1940s saw Parker migrate to New York, where he found his kindred spirits: trumpeter John Birks “Dizzy” Gillespie, pianist Thelonious Monk, guitarist Charlie Christian, and drummer Kenny Clarke. Together, after hours at clubs like Minton’s Playhouse and Monroe’s Uptown House, they deconstructed swing standards, speeding up the tempos, inserting new, complex chords, and crafting melodies that were angular, rhythmically unpredictable, and breathtakingly virtuosic.

The 1940s were his decade of creative explosion. His recordings for the small Dial and Savoy labels, including the legendary “Koko” (1945), based on the changes of “Cherokee,” announced the arrival of a fully formed revolutionary. However, this period was also marred by the severe drug and alcohol addiction that had begun in his teens. His life became a cycle of musical triumphs and personal disasters: missed gigs, erratic behavior, and deteriorating health.

The 1950s saw Parker achieve the status of a legendary figure, touring extensively, recording for a major label (Verve), and even performing with strings—a lifelong dream that produced albums like Charlie Parker with Strings. Yet, his body was failing. Years of substance abuse had taken a catastrophic toll. On March 12, 1955, while watching television at the Manhattan apartment of his friend and patron, Baroness Pannonica de Koenigswarter, Charlie Parker died at the age of 34. The coroner mistakenly estimated his age to be between 50 and 60, a grim testament to the physical damage he had endured. The cause of death was listed as lobar pneumonia and a bleeding ulcer, but the true cause was the relentless pace of his life and addiction. As the graffiti that subsequently appeared across New York proclaimed: “Bird Lives.” His body was gone, but his spirit had permanently infused the air.

Music Style and Improvisational Genius

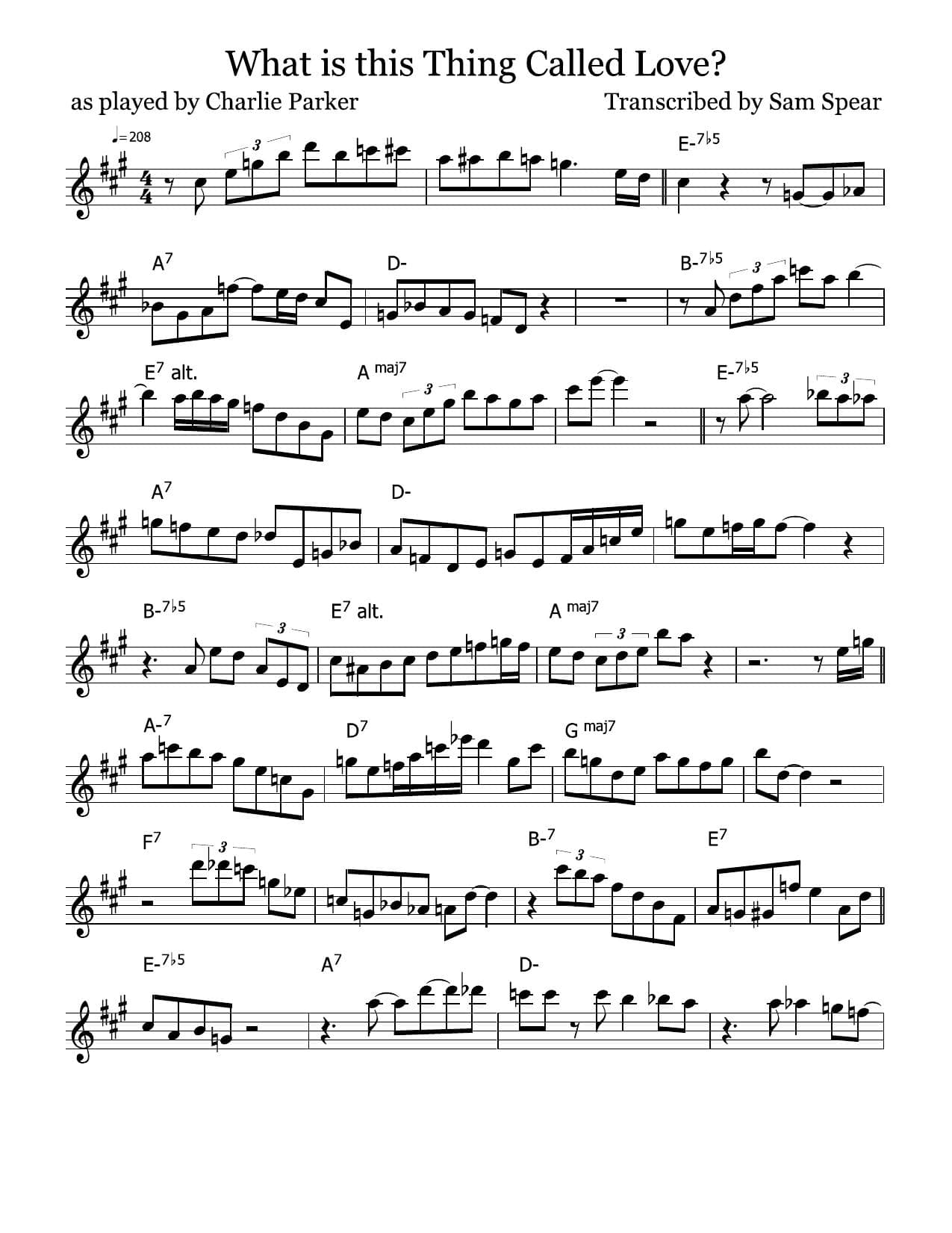

Bebop, as pioneered by Parker and Gillespie, was a musician’s music. It was faster, more harmonically complex, and more rhythmically intricate than swing. It was meant for listening, not for dancing. Parker’s style was its most potent expression.

Tone and Phrasing: Parker possessed a uniquely piercing, vibrant, and intense tone on the alto saxophone. It was full-bodied, cutting through any ensemble with a crying, vocal-like quality. His phrasing was revolutionary. Unlike the smoother, more legato lines of earlier swing saxophonists like Johnny Hodges, Parker’s lines were dense, packed with rapid-fire eighth notes that tumbled out in long, asymmetrical phrases. He would often start a phrase on a weak beat or off-beat, creating a constant sense of propulsion and surprise.

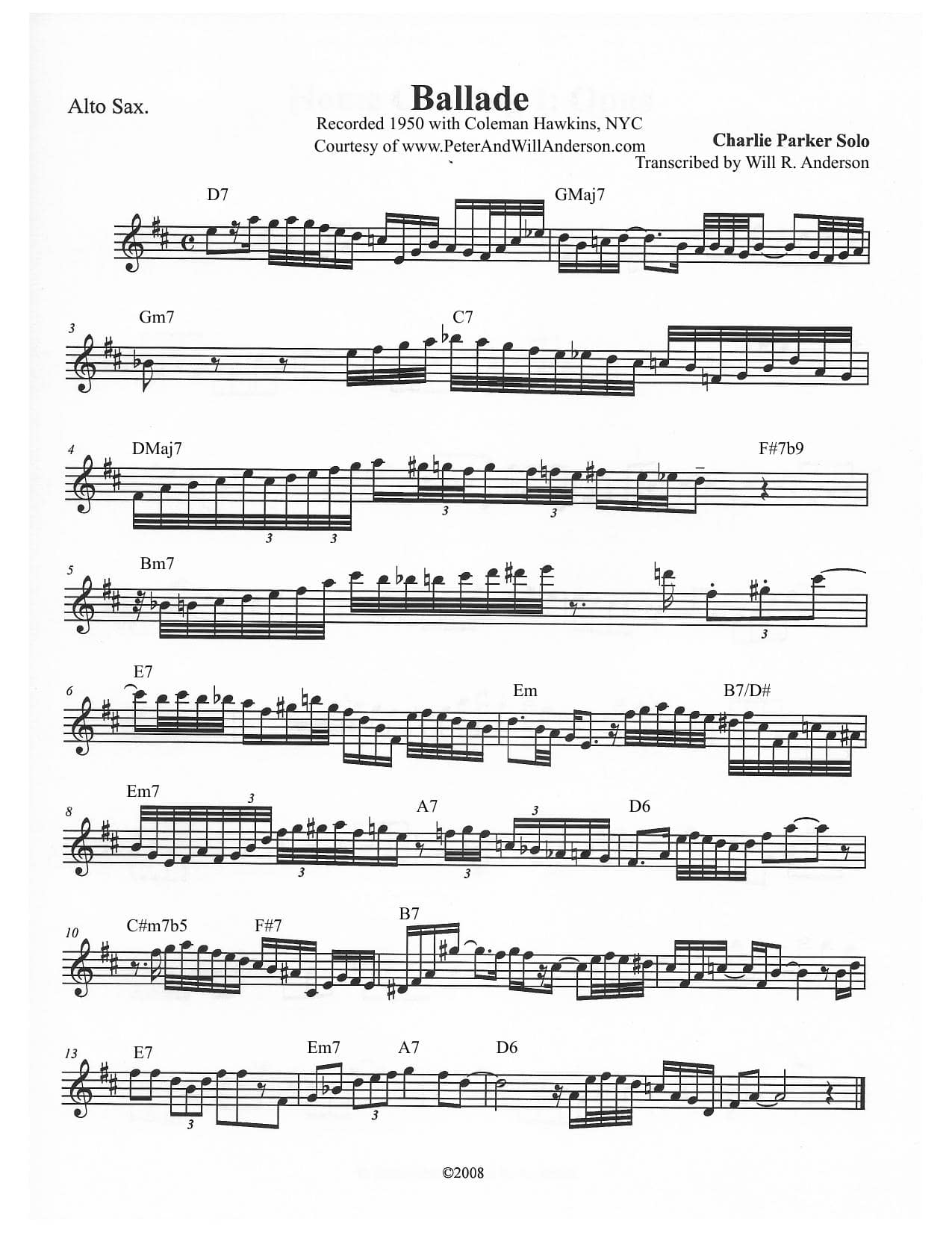

The Parker Lick: While his improvisations were endlessly inventive, certain “Parker licks” or motifs became foundational vocabulary for all jazz musicians that followed. These were often built on arpeggiated chords, chromatic passing tones, and the use of the flatted fifth (or tri-tone), a dissonant interval that became a bebop trademark. A classic example is his line on “Now’s the Time,” a simple blues riff that encapsulates his melodic genius. His solos were not just strings of notes; they were complete, logical compositions in themselves, with their own narrative arc, tension, and release.

Rhythmic Innovation: Parker’s rhythmic conception was perhaps his most radical contribution. He mastered the art of “displacement,” starting a recurring melodic pattern on a different beat each time it appears. He layered complex rhythmic patterns over the steady 4/4 pulse of the ride cymbal, creating a polyrhythmic feel that was exhilarating and challenging. His time feel was impeccable; no matter how complex his lines became, he always swung ferociously.

Chord Progressions and Music Harmony

Parker was a harmonic revolutionary. He and his bebop colleagues didn’t invent new chord progressions so much as they radically embellished existing ones.

Reharmonization: Bebop musicians took the standard chord progressions of popular songs from the Great American Songbook (e.g., “I Got Rhythm,” “How High the Moon”) and superimposed new, more complex chords onto them. They would add chord extensions (9ths, 11ths, 13ths), insert passing chords (like the iconic “bebop dominant” chord), and use substitute chords to create a richer harmonic landscape for improvisation.

For example, on the standard “Cherokee,” Parker didn’t just play the melody; he used its chord progression as a runway for “Koko,” launching into solos that outlined altered chords, substitutions, and chord-scale relationships that were decades ahead of their time. His original compositions, like “Confirmation,” “Anthropology” (based on “I Got Rhythm” changes), and “Yardbird Suite,” feature intricate, original progressions that became new standards in the jazz repertoire.

The Bebop Scale: A key technical innovation was the development of the “bebop scale.” This is essentially a major, dominant, or minor scale with an added chromatic passing tone (often a major 7th in a dominant scale or a raised 5th in a major scale). This allowed musicians to play scalar passages in even eighth notes and still land on chord tones on the strong beats, making their lines flow with incredible smoothness and logic. Parker was the undisputed master of this technique.

Cooperation with Other Artists

Parker’s most significant partnership was with Dizzy Gillespie. They were the twin engines of the bebop revolution: Parker the fiery, rebellious genius of the saxophone, and Gillespie the brilliant theorist, showman, and trumpeter who could articulate the movement’s intellectual underpinnings. Their musical dialogue, heard on classics like “Shaw ‘Nuff,” “Dizzy Atmosphere,” and “Hot House,” was a breathtaking display of telepathic interplay, harmonic daring, and blinding speed.

His working quintet in the late 1940s, featuring a young Miles Davis on trumpet, Duke Jordan on piano, Tommy Potter on bass, and the incredible Max Roach on drums, is considered one of the most important small groups in jazz history. This band was a laboratory where the bebop language was refined and perfected. The interplay between Parker’s alto and Davis’s more lyrical, spacious trumpet created a perfect textural contrast.

Other vital collaborators included:

- Bud Powell: The pianist who translated Parker’s saxophone language to the keyboard.

- Thelonious Monk: The idiosyncratic composer whose unique harmonic world complemented Parker’s.

- Dexter Gordon and Wardell Gray: Tenor saxophonists who adapted the bebop language to their instrument.

- Machito: His collaborations with the Afro-Cuban orchestra expanded bebop’s rhythmic palette, foreshadowing Latin jazz.

Influences and Legacy

Influences on Parker: Parker’s style was a synthesis of his predecessors. He studied the blues phrasing of Lester Young, the technical command of saxophonist Benny Carter, the harmonic ideas of pianist Art Tatum, and the rhythmic drive of bassist Jimmy Blanton. He absorbed everything from the Kansas City blues of Count Basie to the classical music of Stravinsky and Bartók.

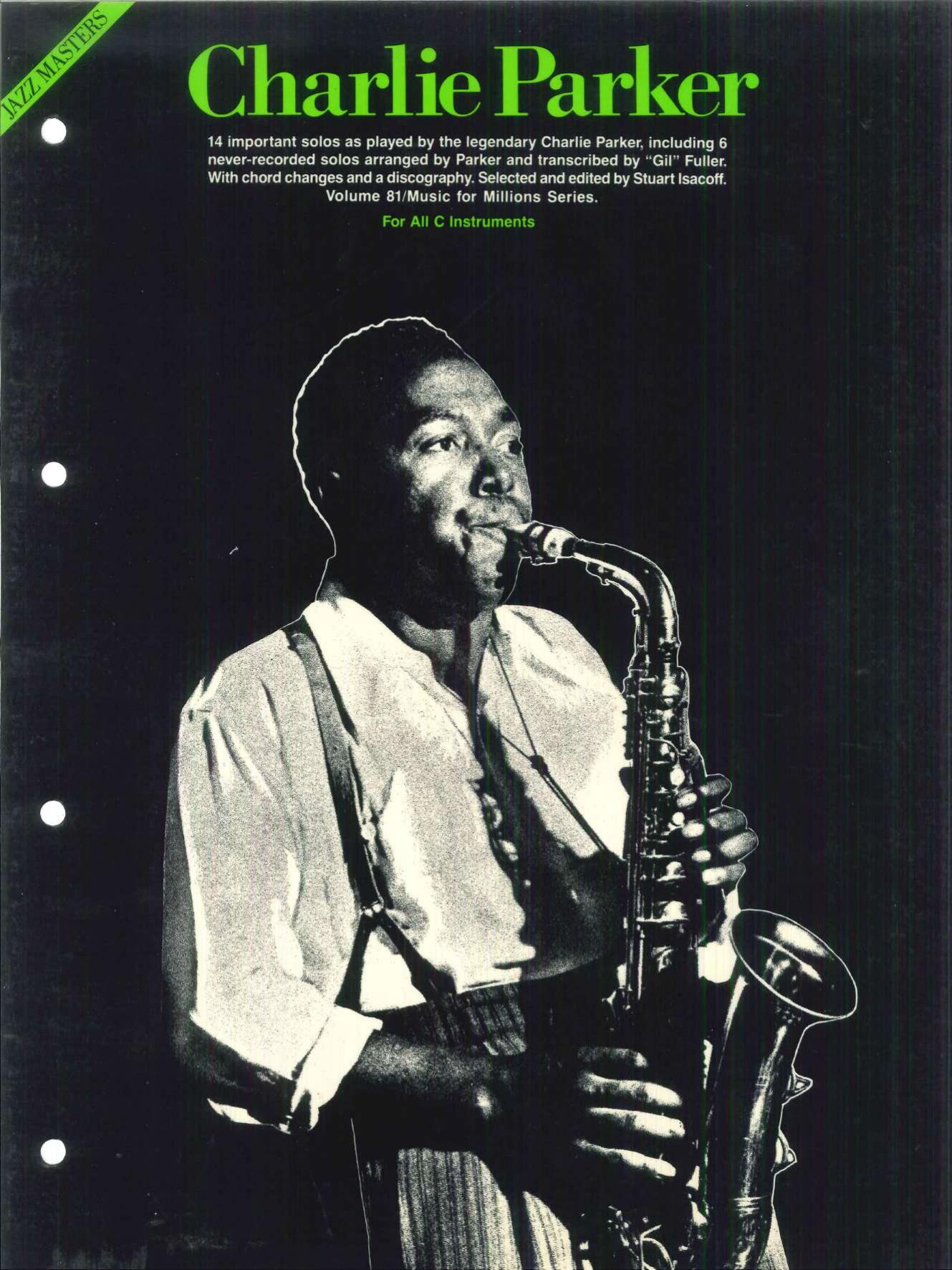

Parker’s Influence: His legacy is immeasurable. Every saxophonist who followed, from Sonny Rollins, John Coltrane, and Cannonball Adderley to present-day artists, speaks the language Parker codified. He moved the jazz soloist to the center of the music, establishing the primacy of improvisation as a form of high art. He elevated jazz from popular dance music to an intellectual, artistic pursuit on par with classical music. His compositions remain fundamental repertoire, studied and played by every serious jazz student worldwide. The Beat Generation writers like Jack Kerouac worshipped him as a symbol of spontaneous, unfettered creativity. He is, quite simply, a pillar of 20th-century art.

Most Known Compositions and Performances

- “Koko” (1945): The definitive bebop recording. Based on “Cherokee,” it features a blistering, unison alto and trumpet line and a Parker solo of staggering velocity and invention.

- “Now’s the Time” (1945): A blues head so catchy it became an R&B hit as “The Hucklebuck.” It demonstrates his ability to create profound art from the simplest forms.

- “Billie’s Bounce” (1945): Another blues masterpiece, featuring one of his most iconic and quoted solos.

- “Confirmation” (1946): An original composition with a complex, flowing melody over an original chord progression, showcasing his skills as a writer.

- “A Night in Tunisia” (1946): His solo on this Dizzy Gillespie composition, particularly his famous break, is a landmark moment in recorded history.

- “Parker’s Mood” (1948): A slow, devastatingly emotional blues that reveals the profound depth of feeling beneath his technical prowess.

- “Just Friends” (1949): From his Charlie Parker with Strings album, a performance of sublime beauty and lyrical grace.

Discography (Key Albums)

Parker’s prime recording years were captured on three main labels:

- Savoy Records (1944-48): The “birth of bebop” sessions. Essential listening: The Charlie Parker Story and Bird: The Complete Savoy & Dial Studio Recordings.

- Dial Records (1946-47): Includes both brilliant performances and recordings that capture his personal struggles. Essential: The Complete Dial Sessions.

- Verve Records (1948-54): His most commercially successful period, including the small group sessions and the “with Strings” projects. Essential: Charlie Parker with Strings, Jazz at Massey Hall (a legendary 1953 live album with Gillespie, Powell, Roach, and bassist Charles Mingus).

Filmography

Parker’s life has been depicted on screen more than that of almost any other jazz musician.

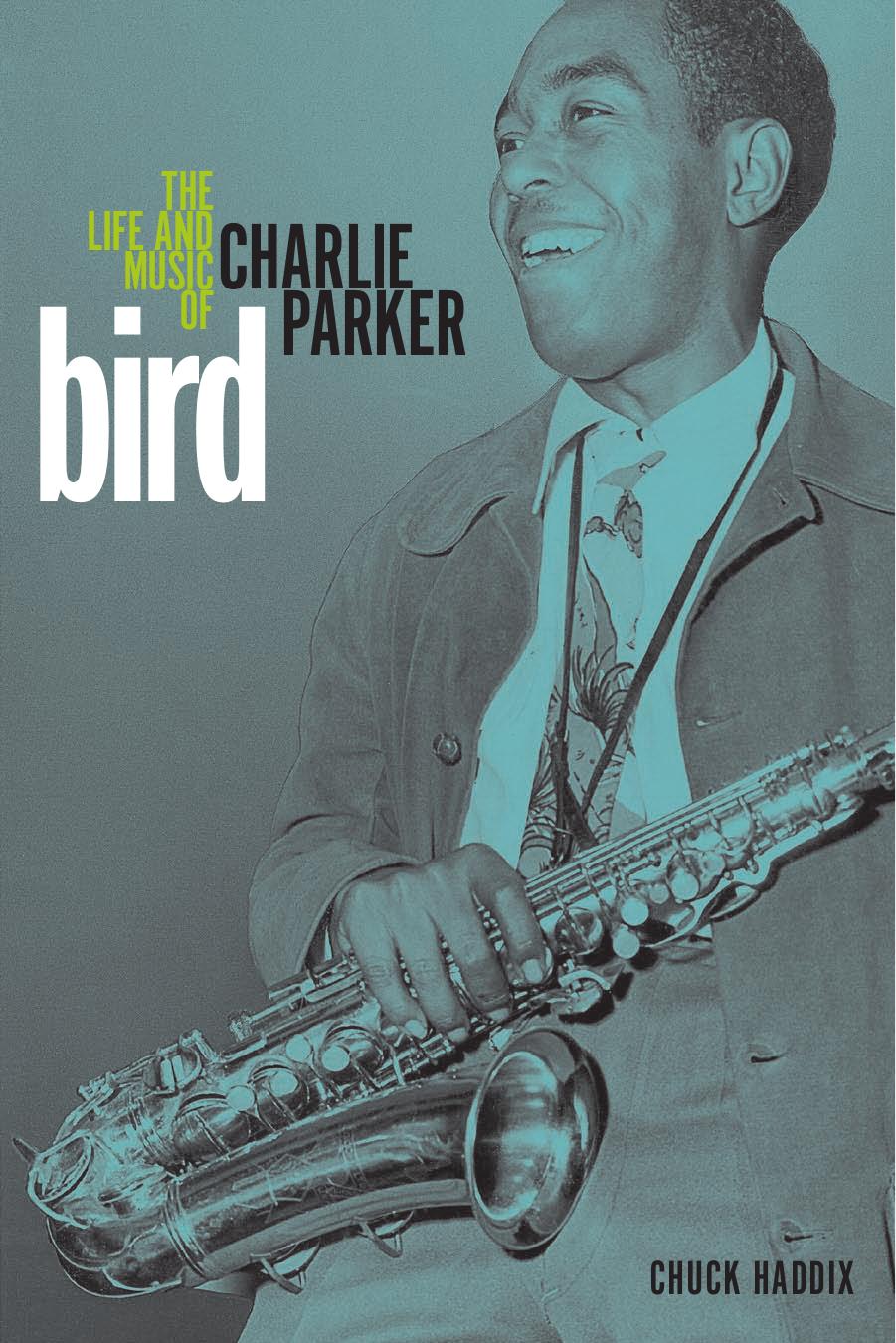

- Documentaries: Celebrating Bird (1987) is an excellent documentary narrated by Parker’s colleague, pianist Lennie Tristano.

- Dramatization: The Clint Eastwood film Bird (1988), starring Forest Whitaker, is a haunting, if romanticized, biopic that won an Academy Award for Best Sound.

Charlie Parker: The Eternal Now’s the Time

Charlie Parker’s life was a race against time. In just over three decades, he consumed and transformed a century’s worth of musical ideas. He was a genius who expanded the possibilities of his instrument, redefined harmony and rhythm for the modern era, and gave jazz a new, sophisticated identity.

His story is a cautionary tale about the cost of addiction, but his music is a permanent testament to the soaring power of the human spirit. He taught us that within the twelve notes of the chromatic scale, there exists an infinite universe of emotion, intellect, and swing. He taught us that “Now’s the Time” is the only time there is to create something beautiful, something true, something that lives on long after the artist is gone. On his birthday, and every day, we remember: Bird Lives.

Search your favorite sheet music in the category of Jazz, Blues, Soul, & Gospel.

Charlie Parker – Live At Rockland Palace September 26, 1952 (1983) (Full Album)

Charlie Parker

Alto Saxophone – Charlie Parker Bass – Teddy Kotick Drums – Max Roach Guitar – Mundell Lowe Piano – Walter Bishop

Recorded: Rockland Palace Dance Hall, New York City, September 26 1952.

Disc 1 A1 Rocker #1 0:00 A2 Moose The Mooche 3:57 A3 Just Friends 8:51 A4 My Little Suede Shoes 11:55 A5 I’ll Remember April (Theme) 16:05 B1 Sly Mongoose 17:22 B2 Laura 22:15 B3 Star Eyes 25:15 B4 This Time The Dream’s On Me 27:46 B5 Easy To Love 33:51 Disc 2 C1 Cool Blues 35:43 C2 What Is This Thing Called Love 39:01 C3 I Didn’t Know What Time It Was 41:08 C4 Repetition 43:44 C5 Lester Leaps In 46:25 D1 East Of The Sun 50:12 D2 April In Paris 53:21 D3 Out Of Nowhere 56:12 D4 Rocker #2 59:00

Charlie Parker & Dizzy Gillespie – Hot House (1952)

In 1952 Charlie Parker & Dizzy Gillespie played this rare TV performance.

Personnel: Charlie Parker – alto sax Dizzy Gillespie – trumpet Dick Hyman – piano Sandy Block – bass Charlie Smith – drums