Come join us now, and enjoy playing your beloved music and browse through great scores of every level and styles!

Can’t find the songbook you’re looking for? Please, email us at: sheetmusiclibrarypdf@gmail.com We’d like to help you!

Table of Contents

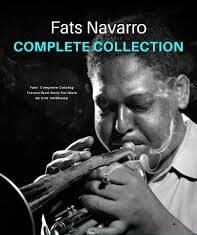

Remembering the legendary trumpeter Fats Navarro, born on this day in 1923 (1923-1950).

Best Sheet Music download from our Library.

Please, subscribe to our Library.

If you are already a subscriber, please, check our NEW SCORES’ page every month for new sheet music. THANK YOU!

Fats Navarro: The Flame That Burned Too Brightly

The history of jazz is punctuated by the lives of artists whose brilliance was so intense, so revolutionary, that it seemed to consume them from within. Theodore “Fats” Navarro is one of those figures—a trumpet virtuoso who, in a tragically brief career spanning just over half a decade, fundamentally reshaped the sound and syntax of the instrument. Alongside his friend and rival Dizzy Gillespie, Navarro was a principal architect of the bebop revolution on trumpet, but he brought to it a uniquely pure tone, a flawless technical command, and a lyrical warmth that set him apart. His legacy is not one of vast quantities of recorded work, but of an unparalleled quality of innovation that continues to inspire musicians to this day.

Browse in the Library:

Or browse in the categories menus & download the Library Catalog PDF:

Biography: A Meteoric Ascent and a Tragic Descent

Early Life (1923-1941)

Theodore Navarro was born on September 24, 1923, in Key West, Florida. His parents, of Cuban and African-American descent, were immigrants, and Spanish was his first language. He began his musical life on piano at the age of six and switched to trumpet at thirteen. His nickname “Fats” was a natural consequence of his large build, a physical trait that would later be tragically contrasted by his emaciated state. Showing immense promise, he played in local bands throughout high school. After graduating in 1941, he left Florida to join a traveling band, a common path for young musicians of the era.

The Big Band Apprenticeship (1942-1945)

Navarro’s first major break came in 1942 when he joined the orchestra of saxophonist Snookum Russell. It was here that he met a pianist who would become a lifelong friend and musical soulmate: J.J. Johnson. More importantly, the band served as a crucible for future talent, including a young Ray Brown and J.C. Heard. Navarro’s raw talent was evident, but he was still playing in a more traditional, swing-oriented style.

His career trajectory changed dramatically in 1943 when he was hired by the celebrated bandleader Andy Kirk. Kirk’s band, “Andy Kirk and His Clouds of Joy,” was a well-established swing outfit. Navarro replaced its star trumpeter, Howard McGhee, who was leaving to pursue the burgeoning bebop scene in New York. McGhee would become a crucial mentor to Navarro, encouraging him to study the new harmonic and rhythmic ideas of bebop. While with Kirk, Navarro’s playing began to evolve, and he made his first recordings. However, the constraints of a big band arrangement limited his opportunities for the extended, harmonically adventurous solos that bebop demanded.

The Bebop Crucible: The Billy Eckstine Orchestra (1945-1946)

In 1945, Navarro received the call that would place him at the epicenter of the jazz revolution. He was hired by vocalist Billy Eckstine to join his revolutionary orchestra. The Eckstine band was nothing less than the first bebop big band, a veritable academy of modern jazz. Its ranks included saxophonists Charlie Parker and Gene Ammons, trumpeter Dizzy Gillespie (though he was leaving around the time Navarro arrived), drummer Art Blakey, and vocalist Sarah Vaughan.

This environment was transformative for Navarro. Surrounded by the creators of bebop, he absorbed their language at an astonishing rate. He became the band’s first trumpet, featured on blistering arrangements of tunes like “Cool Breeze” and “Second Balcony Jump.” His technique blossomed, and he developed the blistering speed, flawless articulation, and harmonic daring that would define his style. It was here that he forged deep musical relationships, particularly with Parker and Gillespie, who recognized him as a peer. However, the lifestyle of the road was grueling, and it was during this time that Navarro, like many of his contemporaries, began using heroin—a decision that would have fatal consequences.

The Solo Star: New York Freelancer (1946-1950)

After leaving the Eckstine band in 1946, Navarro settled in New York City, quickly becoming one of the most in-demand musicians on the vibrant 52nd Street scene. He was a regular at legendary clubs like The Three Deuces and The Royal Roost, often sharing the stage with Charlie Parker. This period marked his artistic maturity. He began recording prolifically as a leader for small labels like Savoy and Blue Note, and as a sideman for a who’s who of bebop.

Despite his rising fame and critical acclaim, Navarro’s heroin addiction was taking a severe toll on his health and reliability. He contracted tuberculosis, which was exacerbated by his drug use. His physical decline was rapid; the man known as “Fats” became gaunt and frail. By 1949, his ability to work consistently was faltering.

Final Days (1950)

Fats Navarro’s final recording session was on June 26, 1950, for the Blue Note label. Just over a month later, on July 7, 1950, he died from complications of tuberculosis, heroin addiction, and malnutrition at the age of 26. His death was a profound shock to the jazz world, a stark reminder of the human cost of the bebop era’s hard-living culture. He was survived by his wife, Rena Clark, and their daughter, Linda.

Music Style and Improvisational Licks: The Sound of Perfection

Fats Navarro’s style is often described as a bridge between the fiery virtuosity of Dizzy Gillespie and the cooler, more lyrical approach of Miles Davis. While he shared Gillespie’s technical prowess and command of the bebop idiom, his sound was distinctly different.

Tone and Sound: Navarro possessed what is widely considered one of the most beautiful trumpet tones in jazz history. It was full, round, warm, and incredibly clear, even at breakneck tempos. Unlike Gillespie’s brighter, more brassy sound, or Davis’s more introspective and muted tone, Navarro’s sound had a luminous, singing quality. He achieved a remarkable consistency across all registers, from the rich, powerful low notes to the clean, piercing high notes.

Phrasing and Rhythm: Navarro was a master of bebop phrasing. His lines were long, flowing, and logically constructed. He had an impeccable sense of time, effortlessly navigating the complex rhythmic subdivisions of bebop. His solos were not just streams of notes; they were melodic narratives with a clear beginning, middle, and end. He made masterful use of space, allowing his phrases to breathe, which added to the lyrical quality of his improvisations.

Characteristic Licks and Techniques:

Navarro’s improvisational vocabulary was built on the foundation of bebop language, but he had several signature traits:

- The Enclosure Technique: A core bebop device where a target note is approached from a half-step above and below. Navarro used this with unparalleled smoothness. For example, to approach a C, he would play a D-flat (the note above) and a B (the note below) before landing on the C. He integrated these enclosures so seamlessly into his lines that they became part of the melodic flow rather than a technical exercise.

- Example: In his solo on “The Squirrel” (with Tadd Dameron), listen to how he gracefully ornaments simple arpeggios with these chromatic approaches.

- Use of Sequenced Patterns: Navarro would often take a short, melodic motif and transpose it diatonically or chromatically through a chord progression. This gave his solos a sense of logical development and intellectual cohesion.

- Example: His famous solo on “Lady Bird” (also with Dameron) is a masterclass in developing simple ideas through sequence, creating a solo that is both inventive and memorable.

- Fluid Arpeggiation: He could rip through complex chord changes using arpeggios (playing the notes of a chord in sequence) with stunning speed and accuracy. However, he always connected these arpeggios with passing tones and chromaticism, avoiding a mechanical sound.

- Lyrical Ballad Playing: While known for uptempo burners, Navarro was a sublime ballad player. On tunes like “I’ll Remember April” (from the album Fats Navarro and Tadd Dameron: The Complete Blue Note and Capitol Recordings), his tone is breathtakingly pure, and his phrasing is tender and vocal-like, demonstrating a deep emotional resonance.

Cooperation with Other Artists

Navarro’s most significant collaborations were central to the development of bebop.

- Tadd Dameron: This partnership between the trumpeter and the pianist/composer/arranger was one of the most fruitful in jazz history. Dameron was the premier composer of the bebop era, crafting intricate, beautiful melodies over sophisticated harmonies. Navarro was the ideal interpreter for Dameron’s music. Their work together, especially the 1947-48 sessions for Blue Note and Capitol, represents the pinnacle of both of their careers. Tunes like “Lady Bird,” “The Squirrel,” “Jahbero,” and “Our Delight” are quintessential bebop compositions, and Navarro’s solos on them are legendary. Dameron provided the perfect canvas for Navarro’s lyrical and technical genius.

- Charlie Parker: Navarro recorded frequently with Bird, both in studio sessions and on legendary live broadcasts from the Royal Roost. On albums like The Band That Never Was and various live compilations, one can hear the remarkable synergy between the two. They shared an unparalleled understanding of harmony and rhythm, pushing each other to greater heights. Navarro was one of the few trumpeters who could match Parker’s inventiveness and velocity.

- Bud Powell: The fiery bebop pianist and the lyrical trumpeter were a potent combination. Their sessions together, such as the famous 1949 meeting for Blue Note (released as The Amazing Bud Powell, Vol. 1), feature some of the most intense and focused music of the era. On “Bouncing with Bud” and “Dance of the Infidels,” Navarro’s blazing lines complement Powell’s percussive attack perfectly.

- Illinois Jacquet: Navarro’s stint with the swing-based tenor saxophonist Illinois Jacquet in 1947 showed his versatility. He could adapt his modern style to a more rhythm and blues-inflected context without sacrificing his musical identity.

Chord Progressions and Music Harmony

Fats Navarro was a master of bebop harmony. His improvisations were not just melodic; they were deeply harmonic inventions.

- Navigating Complex Changes: The standard bebop repertoire was built on complex chord progressions, often based on the framework of standard songs but modified with substitute chords and faster-moving harmonic rhythms. Navarro excelled at navigating these changes. Tunes like “Donna Lee” (based on the chords of “Indiana”) or “Ornithology” (based on “How High the Moon”) required the soloist to outline the harmony clearly and creatively. Navarro’s lines always clearly reflected the underlying chord structure, often implying extensions like 9ths, 11ths, and 13ths.

- Use of the Bebop Scale: Navarro made extensive use of the dominant bebop scale (a mixolydian scale with an added passing chromatic note) to create lines that would land on chord tones on the strong beats. This is a key reason why his solos, even at high speeds, sound so rhythmically secure and harmonically precise.

- Playing “Outside”: While firmly rooted in the chord changes, Navarro, like Parker and Gillespie, would occasionally use chromaticism to create tension, playing notes outside the immediate harmony before resolving back in. He did this with taste and control, always serving the musical narrative.

- Interaction with Dameron’s Harmonies: Tadd Dameron was a harmonic genius, known for his rich, impressionistic chord voicings. Navarro’s ability to improvise melodically over Dameron’s complex harmonies (“Lady Bird” is a prime example) demonstrates a profound intuitive and intellectual understanding of music theory. He didn’t just play the scales; he crafted melodies that enhanced and commented on the harmonic landscape Dameron created.

Influences and Legacy

Influences: Navarro’s primary early influence was the swing-era trumpeter Roy Eldridge, whose fiery, high-note style was a direct precursor to bebop. Through Howard McGhee, he was introduced to the ideas of Dizzy Gillespie, who became his most significant influence in terms of bebop language. However, Navarro synthesized these influences into a style that was entirely his own.

Legacy: Fats Navarro’s legacy is immense. He is the direct stylistic forefather of a generation of trumpet masters who defined the “cool” and “hard bop” eras.

- Clifford Brown is the most direct descendant. Brown studied Navarro’s recordings obsessively, adopting his warm tone, flawless technique, and lyrical approach. Brown’s career, though also tragically short, picked up where Navarro’s left off and carried the trumpet tradition forward.

- Lee Morgan, Freddie Hubbard, and Woody Shaw all cited Navarro as a key influence. His combination of power, precision, and lyricism became the gold standard for modern jazz trumpet.

His legacy is one of “what if?”—a profound sense of loss for the music that was never made. Yet, the music he left behind remains a timeless benchmark of technical excellence and profound musicality.

Works, Filmography, and Discography

Most Known Compositions and Performances:

While primarily an interpreter, Navarro did compose a few tunes, including “Barry’s Bop,” “Nostalgia,” and “Fats Blows.” However, his most famous performances are on compositions by others:

- “Lady Bird” (with Tadd Dameron) – The quintessential Navarro solo.

- “The Squirrel” (with Tadd Dameron) – A showcase for his bluesy, lyrical side.

- “Jahbero” (with Tadd Dameron) – Demonstrates his power and range.

- “Bouncing with Bud” (with Bud Powell) – A masterclass in uptempo playing.

- “Double Talk” and “Dopamine” (from sessions with Charlie Parker).

Filmography:

Regrettably, no known film footage of Fats Navarro performing exists. His career predated the era of widespread television broadcasts of jazz performances. Our only record of his art is audio.

Discography (Selective):

Navigating Navarro’s discography can be complex due to the abundance of compilations. The most essential recordings are:

- The Fats Navarro Project (Various Labels) – A comprehensive 4-CD box set that collects nearly all of his studio work as a leader and sideman. This is the definitive collection.

- Fats Navarro and Tadd Dameron: The Complete Blue Note and Capitol Recordings (Blue Note) – The absolute core of his legacy. Essential listening.

- The Amazing Bud Powell, Vol. 1 (Blue Note) – Features Navarro on several pivotal tracks.

- Charlie Parker: The Complete Royal Roost Performances (Savoy) – Captures Navarro live with Parker at the height of his powers.

- Fats Navarro Featured with the Tadd Dameron Band (Milestone) – A well-curated single-album introduction.

In conclusion, Fats Navarro was more than just a brilliant trumpet player; he was a complete musician whose ideas about melody, harmony, and rhythm helped define one of jazz’s most creative periods. His story is a tragedy of unfulfilled potential, but his recorded legacy is a monument to an artist who, in a fleeting moment, achieved perfection. The flame burned with an incandescent brightness, and though it was extinguished far too soon, its light continues to guide musicians nearly three-quarters of a century later.