Come join us now, and enjoy playing your beloved music and browse through great scores of every level and styles!

Can’t find the songbook you’re looking for? Please, email us at: sheetmusiclibrarypdf@gmail.com We’d like to help you!

Table of Contents

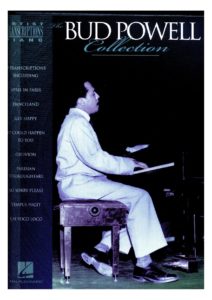

Remembering Bud Powell, born on this day in 1924 (1924-1966).

Best Sheet Music download from our Library.

Please, subscribe to our Library.

If you are already a subscriber, please, check our NEW SCORES’ page every month for new sheet music. THANK YOU!

The Tempestuous Genius: Bud Powell and the Birth of Modern Jazz Piano

In the crucible of bebop, a revolutionary sound that erupted in the dimly lit clubs of 1940s New York, a handful of young musicians forged a new language for jazz. While Charlie Parker and Dizzy Gillespie are rightly hailed as the architects of this movement on saxophone and trumpet, it was a quiet, intensely fragile young man from Harlem who translated their complex harmonic and rhythmic innovations to the piano: Earl “Bud” Powell. More than just an accompanist or soloist, Powell fundamentally redefined the instrument’s role, liberating the right hand to play horn-like, linear melodies while anchoring the rhythm with sparse, chordal punctuations in the left. His life was a tragic arc of breathtaking artistic triumph shadowed by profound personal suffering, a story of a genius who poured all of his turbulence, his brilliance, and his pain directly onto the keyboard.

Early Years: A Prodigy in Harlem

Born on September 27, 1924, in New York City, Bud Powell was immersed in music from infancy. His grandfather was a flamenco guitarist, and his father, William Powell, was a stride pianist. Bud began studying classical piano at age five, showing immediate prodigious talent. By his early teens, he was already playing in his father’s band and was deeply influenced by the reigning piano king of swing, Art Tatum. Tatum’s virtuosic flow would always remain a foundation for Powell, but soon a new, more urgent sound would capture his imagination.

As a teenager, Powell became a regular on the vibrant Harlem jazz scene, particularly at places like Minton’s Playhouse and the Uptown House. These were the laboratories where bebop was being invented. He fell under the wing of the movement’s pioneers, especially pianist Thelonious Monk, who was seven years his senior. Monk became a mentor and a lifelong friend, recognizing Powell’s unique talent early on. It was Monk who famously presented the young pianist at his first major gig at the Apollo Theatre and who composed “In Walked Bud” in his honor.

Browse in the Library:

Or browse in the categories menus & download the Library Catalog PDF:

The Bebop Revolution: Translating Bird and Diz to the Piano

The core challenge for pianists in the bebop era was to find their place in music that was increasingly focused on blistering tempos and intricate melodies played by horns. The old stride and swing styles, with their busy left-hand patterns, now felt cumbersome and rhythmically obstructive.

Bud Powell’s revolutionary solution was one of brilliant simplification and re-orchestration. He distilled the piano’s function into two essential roles:

- The “Right Hand as a Horn”: Powell’s single-note lines were unparalleled. He developed a blindingly fast, impeccably articulate technique that allowed him to weave through chord changes with the same fluidity and inventiveness as Charlie Parker. His solos were not merely collections of licks; they were cohesive, melodic narratives full of surprise, passion, and a deep, swinging feel. Tunes like “Celia” and “Bouncing with Bud” are masterclasses in this linear, horn-like improvisation.

- The Sparse, Chordal Left Hand: Instead of walking bass lines or striding patterns, Powell’s left hand became a rhythmic anchor. He would drop in crisp, syncopated chords—often just on the second and fourth beats of the measure (the “upbeats”)—to outline the harmony and propel the rhythm section. This approach freed the piano from its rhythmic duties and integrated it seamlessly with the bass and drums, creating a more modern, ensemble sound.

This style became the blueprint for modern jazz piano. Virtually every pianist who emerged after him—from Al Haig and Duke Jordan to Bill Evans, McCoy Tyner, and even Herbie Hancock—built upon the foundation Powell laid.

The Triumphant Recordings: The Blue Note and Verve Sessions

Despite a life marred by instability, Powell’s recorded output in the late 1940s and early 1950s constitutes one of the most important bodies of work in jazz history. His sessions for the Blue Note and Verve labels, particularly the seminal “The Amazing Bud Powell, Vol. 1” (1949-1951), are ground zero for modern jazz piano.

It is here that we find his most iconic compositions and performances:

- “Un Poco Loco”: A hypnotic, Afro-Cuban infused piece built on a simple, repetitive bass line. Powell’s solo is a study in rhythmic obsession and creative variation, a masterpiece of controlled frenzy.

- “Dance of the Infidels”: A challenging, up-tempo blues that has become a standard jam session tune, showcasing his ability to navigate complex harmony at breakneck speed.

- “Parisian Thoroughfare”: A vivid tone poem that evokes the sounds of a busy Paris street, alternating between a bustling, rhythmic theme and a lyrical, impressionistic interlude.

- “Glass Enclosure”: A haunting, through-composed piece that reflects the confinement and isolation he felt during his many institutionalizations.

These recordings capture Powell at the peak of his powers. His touch is sharp and precise, his ideas flow with seemingly effortless genius, and the emotional intensity is palpable.

The Shadow of Suffering: Racism, Illness, and Institutionalization

To discuss Bud Powell’s art is to inevitably confront his devastating personal struggles. In 1945, he was severely beaten by police in Philadelphia, suffering a head injury that his family and friends believed triggered a lifetime of mental health problems, including severe depression and erratic behavior. He was diagnosed with what was then called schizophrenia and underwent multiple hospitalizations, including periods at Creedmoor State Hospital where he was subjected to electroconvulsive therapy, a traumatic treatment that likely dulled his faculties.

His life became a cycle of creative bursts followed by breakdowns. The racism of the era, combined with a lack of understanding of mental health, meant he received little effective care. He self-medicated with alcohol, which exacerbated his condition. The music that sounded so lucid and powerful on record was often created in moments of fragile clarity between periods of deep torment. His composition “Glass Enclosure” is a direct musical metaphor for the sanitarium room his guardians would confine him to, a poignant cry from an artist trapped within his own mind.

The Parisian Exile: A Bittersweet Finale

In 1959, seeking escape from the pressures and racism of America, Powell followed a wave of Black jazz expatriates to Paris, accompanied by his friend and protector, Francis Paudras, whose devotion was later immortalized in Bertrand Tavernier’s film Round Midnight.

For a time, Paris offered a respite. He was revered as a legend by European audiences and enjoyed a period of relative stability and productivity. Recordings from this period, such as A Portrait of Thelonious and Blues for Bouffemont, show flashes of his former brilliance, though the fiery technique of his youth had begun to wane, replaced by a more reflective, sometimes fragile approach. However, his health continued to deteriorate due to alcoholism and tuberculosis. He returned to New York in 1964, but the comeback was short-lived. He played his final gig at Birdland in 1965 and died on July 31, 1966, at the age of 41, from a combination of alcoholism, malnutrition, and tuberculosis.

Legacy: The Eternal Voice of Modern Piano

Bud Powell’s life was a tragedy, but his artistic legacy is one of indomitable triumph. He was the essential conduit, the musician who took the language of bebop and codified it for the piano, making it possible for all who followed.

His influence is inescapable. When you hear the crystalline right-hand lines of Bill Evans, the rhythmic thrust of McCoy Tyner, or the harmonic daring of Chick Corea, you are hearing echoes of Bud Powell. He transformed the piano from a rhythm instrument into a full-fledged solo voice in the modern jazz ensemble.

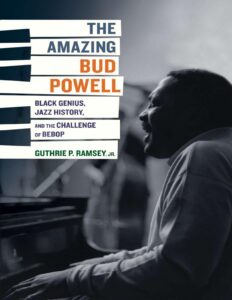

More than just a technical innovator, Powell was a profound musical poet. His compositions are not just vehicles for improvisation; they are deeply personal statements that range from joyous exuberance to melancholic introspection. In every note he played, one can hear the full spectrum of human emotion—the brilliance, the rage, the sorrow, and the sublime beauty. He was, as the title of one biography aptly calls him, “a genius in the night,” a fleeting, incandescent light whose burn forever changed the landscape of jazz.

Bud Powell, at the Antibes Jazz festival, July 13th, 1960 (colorized)

Browse in the Library:

Or browse in the categories menus & download the Library Catalog PDF: