Table of Contents

John Coltrane’s improvisation style analysis (sheet music incl.)

John Coltrane – I Want To Talk About You (LIVE improvisation)

Pattern in melodic improvisation and harmonic progression in the music of John Coltrane.

John Coltrane (1926-1947) was a leading African-American jazz musician, performing mainly on tenor and soprano saxophones. Coltrane’s music is renowned for its fiery creativity and the saxophonists visceral approach. This uninhibited style has led some listeners to be dismissive of his style, considering his note choice to be random and meaningless.

This is particularly true of his more unhinged performances,

such as the seminal free jazz album Ascension and the cadenza which follows his performance of “I Want to Talk about You” on the album Live at Birdland.

The words of Associate Editor of prominent jazz publication Downbeat, John Tynan, who stated (Down Beat Magazine,) on listening to a 1961 performance of the saxophonist, “that [he] listened to a horrifying demonstration of what appears to be a growing anti-jazz trend exemplified by those foremost proponents [Coltrane and fellow saxophonist, Eric Dolphy] of what is termed avant-garde music” exemplify this trend.

Coltrane’s motivation for playing these kinds of free cadenzas is touched upon in The New Grove Dictionary of Jazz, where it is stated that in pieces such as Giant Steps, Coltrane, by seeking to escape harmonic clichés had inadvertently created a one dimensional improvisatory style.

In the late 1950s, he pursued two alternative directions. First, his expanding technique enabled him to play what the critic Ira Gitler called sheets of sound. It is these sheets of sound that can be heard clearly in the cadenza to I Want to Talk About You. Furthermore, Barry Kernfeld comments that such flurries …. disguised his excessive reiteration of formulae. By revealing Coltrane’s techniques, we think we may inspire many modern Jazz improvisers and musicians.

Coltrane’s cadences

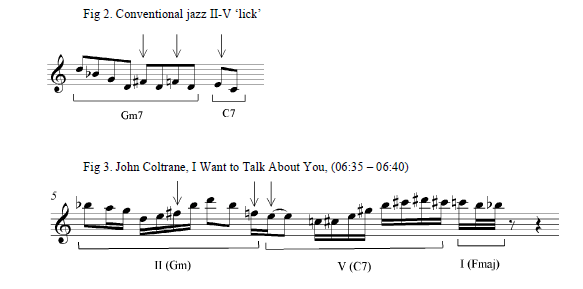

If we analyze the above section in depth, it is possible to see it as implying a II-V-I cadence typical of the jazz idiom, one that Coltrane would have been very familiar with.

An example of such a cadence would be the Dm7 G7 Cmaj7 that comes in the last 4 bars of a conventional jazz 12 bar blues in C major. This extract is to some degree a pastiche of the clichéd jazz lick shown below, which is often played over a II-V-I cadence.

Particularly from bar 5 in Coltrane’s phrase, we see the guide tone of F# (implying the chord of G minor with a major 7th) descend to an F (implying G minor with a lowered 7th) and then to an E (forming the 3rd of C7). Fig. 3 above indicates these common guide-tones with arrows.

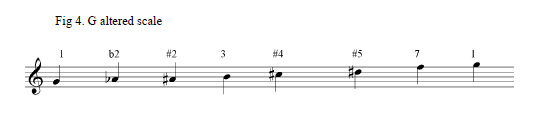

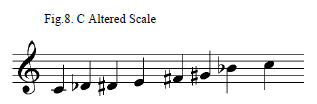

A scale that jazz musicians commonly use over dominant seventh chords is the altered scale. This scale is a mode of the melodic minor scale, and is formed by starting on the leading note of that scale.

Over a tonality of G7, this scale emphasizes all the notes that are outside the conventional sound of the chord, and so is typical of harmonically complex jazz.

In How to Comp, Hal Crook describes this effect as altered tensions (Hal Crook, How to Comp, (Advance Music, 1995) p.17). Notably, the 3rd (B) and 7th (F) are not altered, as this would too drastically change the function of the chord.

In addition to playing the scale linearly, one can also derive a number of shapes and patterns from it. Just as we can derive F and G major triads from the C major scale, we can derive C# and D# major triads from the G altered scale.

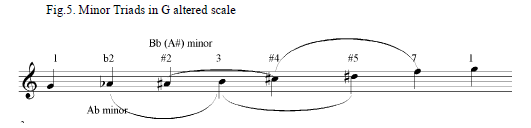

Below, we see how both Ab and Bb(A#) minor triads are also built into the altered scale.

It is the minor triad that is built on the b2 of the scale that Coltrane uses in this extract.

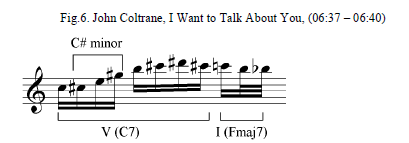

Here we see, in the context of a C dominant seventh chord, a C# minor triad. This is a clear indication of Coltrane deriving the minor triad shape from the C altered scale.

We can see many examples of Coltrane superimposing harmony over existing chord changes outside this cadenza.

Coltrane will often use triadic or arpeggaic constructions

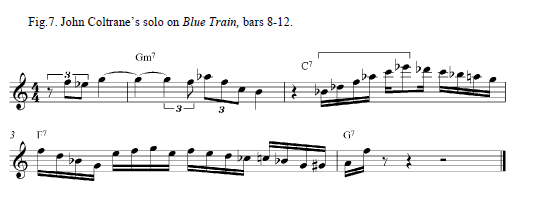

as these are often the clearest ways to describe harmony. An example might be bars 9-12 of the saxophonists solo on Blue Train from the album of the same name. Blue Train, as its name suggests, is a 12 bar-blues in the key of Eb.

Therefore, the last 4 bars of each 12 bar chorus contain a II-V-I cadence in the key of Eb. In his solo, Coltrane does not stick rigidly to the chords of Fm7 – Bb 7 – Eb 7, but instead implies contrasting harmony over the top.

The key section is shown with the square brackets. In this section, Coltrane is not using the altered scale over the C7 chord, as the F natural used in the line does not fit into that scale.

Instead, it appears that Coltrane is implying a minor plagal cadence over the chord changes. Since a plagal cadence is the resolution from chord IV to chord I, a minor plagal cadence is the resolution from chord IV minor to chord I.

In this case, that resolution is from the clear Bb minor shape indicated by the square brackets to the F natural that is the first note of the next bar. This example demonstrates that Coltrane was not limited to altered scale vocabulary in his harmonic language.

Repeating Motifs

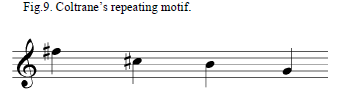

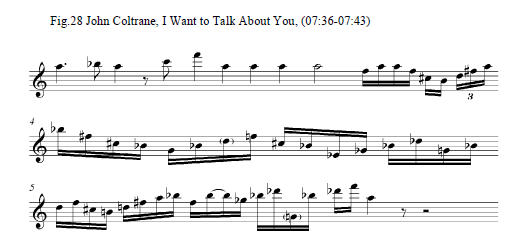

In the cadenza, Coltrane does repeat certain ideas that demonstrate that his improvisation is to some degree based on things that he has assimilated and practiced rather than being completely wild and free. One such motif is heard twice, once at (06:16) and again at (06:24).

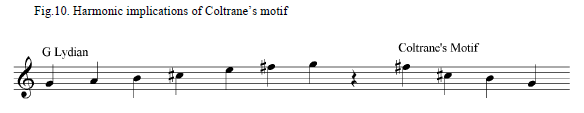

If we assume that this pattern is derived from a diatonic scale or mode, there are several possible harmonic interpretations of it. The one I thought of at first was that it

could imply the tonality of G Lydian.

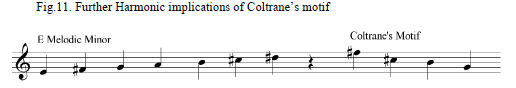

Similarly, it could be descriptive of the church modes of D. On the other hand, the notes of the motif fit into the scale of E melodic minor.

These and other interpretations are possible, and nobody can definitely state what Coltrane was thinking.

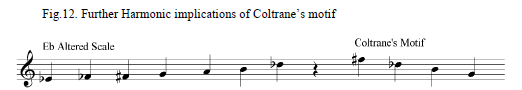

However, Mornington Lockett has suggested that the motif could imply several of the altered tensions over the chord of Eb 7. All the notes of the motif fit into the Eb altered scale. Remember that the altered scale is the same as the melodic minor scale a semitone up, and so just as the motif fits into E melodic minor scale, it fits into the Eb altered scale

This is possibly the most practical use of this shape for jazz improvisers, as dominant seventh chords are extremely common in jazz harmony.

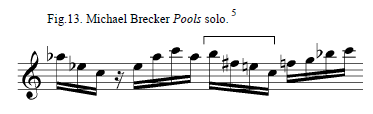

If we look at this motif in its historical context, there are several interesting things about it. The first is that we can see the late Michael Brecker, a celebrated saxophonist and devotee of John Coltrane’s music, using an identical shape in bar 92 of his solo on the piece Pools by the jazz fusion group Steps Ahead.

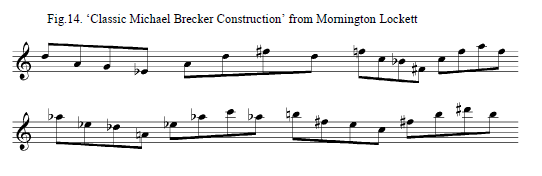

The brackets indicate the relevant segment; we can see that it is simply a transposed version of the original Brecker construction. This pattern is well known and attributed

to Brecker. On his website, Mornington Lockett refers to a version of this pattern as a classic Michael Brecker construction.

The relationship between Breckers pattern and the motif by Coltrane is clear. It seems very likely that Brecker, who is known to have transcribed a great deal of Coltrane’s music, heard this motif (perhaps subconsciously) and created his version of it.

This is a very exciting discovery, and it surely demonstrates how artists as great as Brecker are very much influenced by their own heroes, just like the novice jazz musician.

Use of Triad Pairs

The use of triad pairs is well documented in jazz. Several books exclusively cover this topic, such as Walt Weiskopfs Intervallic Improvisation: The Modern Sound and

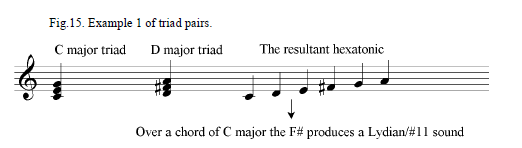

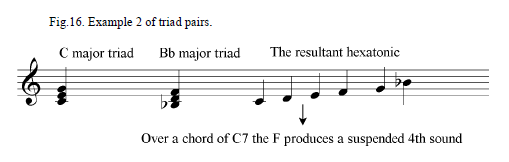

Gary Campbells Triad Pairs for Jazz. The most common technique is to alternate the use of two triads, creating a hexatonic (six note) scale.

However, as Jason Lynn states in his article on the technique, in order for this approach to yield a hexatonic (six note) scale, the two triads must be mutually exclusive they must contain no common tones.

This technique can create some very interesting colors of tonality. Below we see how two major triads (the most common pairing of triads) can produce, on a major

chord, a Lydian or #11 sound.

Similarly, over a dominant 7th chord, two major triads can produce the sound of a suspended 4th, or, as it would be known to jazz musicians, a sus chord.

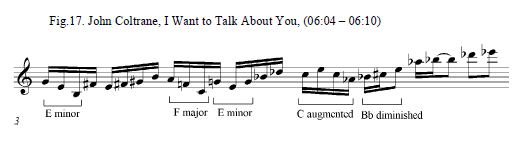

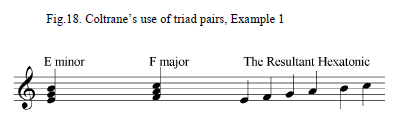

In Coltrane’s cadenza on I Want to Talk About You we can clearly see his use of this technique.

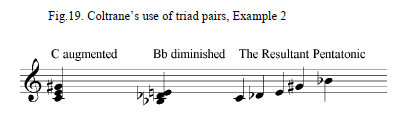

Here we see the alternating of E minor triad and F major triad along with C augmented triad and Bb diminished triad.

Since Coltrane is not playing over a fixed chord sequence at this point, it is harder to decipher what tonality this triad pair implies.

The most obvious would be that of C major with a #11, i.e. the church mode of C Lydian. Because a diatonic scale cannot contain 3 semitones next to one another, the missing seventh note from the hexatonic must be D, as either Db or D# would result in a non-diatonic scale.

This would indicate that the tonality implied must be that of one of the church modes of C.

However, as we will see by Coltrane’s use of synthetic scales, there is no need for us to be bound to the conventions of diatonic scales in our analysis of his music.

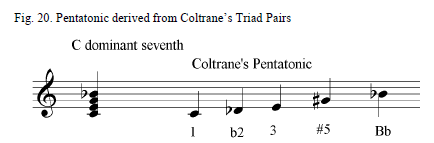

In this example, the triad pairs are not mutually exclusive, and so together create a pentatonic scale rather than a hexatonic. This pentatonic is very interesting and could

be used to describe several advanced jazz harmonic sounds.

This is perhaps one of the most attractive of its possible manifestations. In the context of a C7 chord, the pentatonic contains two altered tensions that are found in the altered

scale that were covered in the first section of this essay. These are the b2 and #5 (Db and G#).

In addition, the natural 3rd (E) and flattened 7th (Bb) mean that the chord’s function is not obscured, the scale only colors it. This is a prime example of how the analysis of Coltrane’s cadenza can produce material that is suitable for

improvisers to absorb into their melodic and harmonic vocabulary.

Use of Synthetic Scales

Synthetic scales can be defined as non-diatonic scales, i.e. scales that are not modes of the major, harmonic major, harmonic minor or melodic minor scales. Examples of

these are the whole-tone scale and the diminished scale. Classical musicians may know these same scales as Messiaens 1st and 2nd modes of limited transposition.

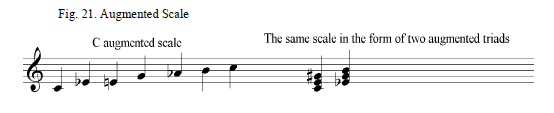

Another example of a synthetic scale is the augmented scale. This is constructed of alternating minor thirds and semitones to form a six note scale (hexatonic). It can also

be thought of as two augmented triads a semitone apart and so another example of the technique of triad pairs that has already been noted.

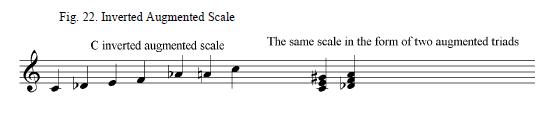

If the order of intervals is reversed so that the scale is now formed by repeating semitone-minor third, this new scale is called the inverted augmented scale.

The following extract can be analyzed and shown to be an example of Coltrane using the inverted augmented scale.

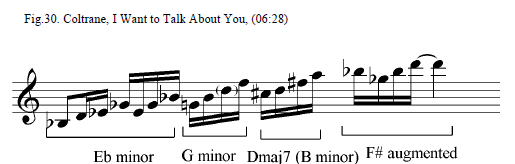

Further analysis can give an indication of the tonalities that Coltrane is implying in this phrase.

This shows how the shape of the augmented scale can be used to outline an augmented tonality, i.e. a chord containing a #5.

One might say that we cannot be sure that Coltrane was thinking of this exact scale when improvising this extract.

However, there is good evidence that the saxophonist

was very familiar with this synthetic scale. In the book, The Augmented Scale in Jazz, Walt Weiskopf and Ramon Ricker admit that in examining improvised solos it appears to the authors that most soloists have used augmented scales and triads in an intuitive manner. It is doubtful that many of the players cited in this book have systematically tried to codify their use of this material.

However, they go on to say that two players that might be an exception to this speculation are John Coltrane and

Michael Brecker.

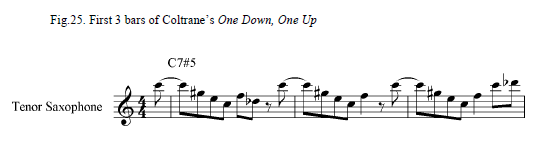

The clearest indicator of Coltrane’s familiarity with the augmented scale is his use of it in his composition One Down, One Up. This piece has a form of AABA and is comparable with Miles Davis composition So What in its use of only two chords each A section is Bb 7#5 throughout and likewise each B section is composed only ofAb 7#5.

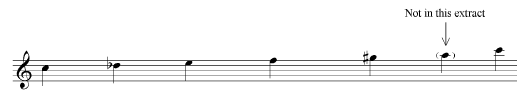

As shown below, this extract from One Down, One Up contains all but one notes of the inverted augmented scale, and includes no tones extraneous to that scale.

Given that this melody was pre-composed and thought-out carefully, we can be almost certain that Coltrane was thinking of an augmented scale as the basis for his

melodic material.

Therefore, we can be confident that the examples of augmented scale material in the cadenza were intentional by the saxophonist.

Use of the Three-Tonic Cycle

To jazz musicians, John Coltrane’s most infamous composition is surely Giant Steps.

This piece is well-known for being a minefield for improvisers, who are often tested on their ability to successfully navigate the treacherous chord changes. In Giant Steps, instead of following most common jazz standards which modulate generally round the cycle of fourths or in tone and semitone shifts, Coltrane takes the major third as the basic for his harmonic movement.

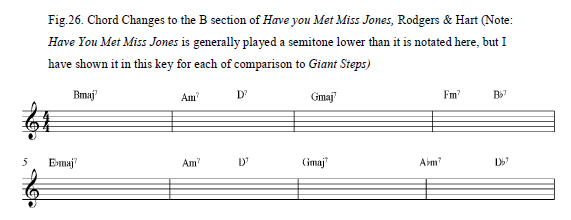

A number of common standards did contain elements of this kind of modulation, such as Rodgers and Harts Have you Met Miss Jones.

As we can see, the initial tonal center of B moves down a minor third to G by way of a traditional II-V-I cadence, typical of jazz harmony.

Notably, in the 6th bar of this bridge the direction of the major third cycle changes, and the Eb tonal centre rises to

G instead of going down to B.

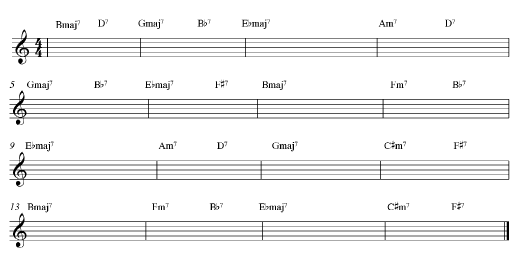

In Giant Steps, Coltrane took this technique to new extremes by using several patterns of modulation to traverse the chord sequence. He made frequent use of the technique of prefixing each new tonic center with its respective II-V cadence, or at least its dominant.

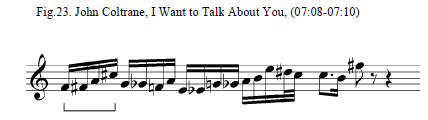

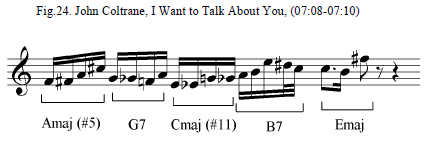

In the extract notated below, we can see evidence of Coltrane using this system of modulation by major third in his improvisation.

At normal speed, this section sounds extremely chaotic, but on closer inspection, there is definite pattern in Coltrane’s use of repeating shapes.

In the above analysis of the key passage from the middle of the extract, Mornington Lockett, an expert on Coltrane’s work, has identified the tonalities that Coltrane is

implying.

We should keep in mind that Gb major is the relative major of Eb minor, and so for the purposes of this analysis we can treat them as indicative of the same general tonality.

Therefore, we can state that the sequence of key centers inside the square brackets is B minor Eb minor G minor Eb minor G minor.

These three centers (B, Eb and G) form an augmented triad, as they are each a major third away from each other. Therefore, this sequence is an example of Coltrane

manipulating the three-tonic cycle that he also used in Giant Steps, by repeating a certain pattern (in this case minor7 arpeggios) in major thirds.

This sequence is comparable to the bridge of Have You Met Miss Jones in that it changes direction round the cycle, i.e. it does not go from G minor to B minor as one might expect but instead to Eb. There are further examples in the cadenza of Coltrane using similar ideas involving repeating a pattern while moving it around in major thirds.

Again the shape being manipulate is that of a minor7 arpeggio and again the relative major of one of the minor chords is implied, in this case D major. While we could

look at both these examples as a textbook use of the three-tonic system, Mornington Lockett has produced a fascinating new interpretation of them.

He realized that by taking all the notes of Gm7, Am7 and Ebm7 and forming a linear scale out of them, you come up with a nine note synthetic scale.

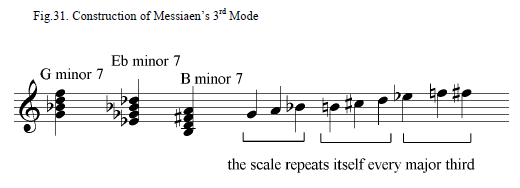

This scale has the interesting characteristic of containing the first three notes of the natural minor scale, repeating every major third. As it turns out, this scale was also used by Messiaen as another in his series of Modes of Limited Transposition, in this case Mode 3.

Nonetheless, we know that Coltrane thought incredibly technically into the harmonic implications of various

patterns, studying Nicholas Slonimsk’s Thesaurus of Scales and Melodic Patterns, in which the Russian-born composer aimed to document all possible combinations of tones.

The relationship between Coltrane and this text is well illustrated in Jeff Bairs dissertation, Cyclic Patterns in John Coltranes Melodic Vocabulary as Influenced by Nicholas Slonimsky’s Thesaurus of Scales and Melodic Patterns.

This all shows that Coltrane analyzed harmony in extreme detail, and it is not inconceivable that he conceived of the implications of Messiaens Mode 3 in relation to his 3-tonic cycle.

Best Sheet Music download from our Library.

Conclusion

Throughout this essay, we have seen much evidence that Coltrane’s improvisation was not random and thoughtless, but instead he considered harmony and scalic patterns in

considerable depth. It is telling that something so seemingly random does in fact have a clear internal logic.

This surely supports Mark Levine when he states in the introduction to his seminal text The Jazz Theory Book that A great jazz solo consists of 1% magic and 99% stuff that is explainable, analyzable, categorizable and doable (Levine, Mark. The Jazz Theory Book, (Petaluma: Sher Music Co) page VII).

In his book Jazz, John Fordham relates an anecdote which illustrates Coltrane’s tendency to play a lot of notes for a long time (demonstrated in this cadenza!):

Apparently, Coltrane told his bandleader Miles Davis that once immersed in a solo, he didn’t know how to stop. Try taking the saxophone out of your mouth, replied Davis.

Please, subscribe to our Library.

If you are already a subscriber, please, check our NEW SCORES’ page every month for new sheet music. THANK YOU!

Browse in the Library:

| Artist or Composer / Score name | Cover | List of Contents |

|---|---|---|

| All Sondheim Vol IV Music and lyrics |

|

All Sondheim Vol IV Music and lyrics |

| All That Jazz piano-vocal Arrangement |

|

|

| All The Things You Are (Guitar And Tabs) | All The Things You Are (Guitar And Tabs) | |

| All The Things You Are (Guitar And Tabs) (Musescore File).mscz | ||

| All The Things You Are By Jerome Kern Guitar Transcription |

|

|

| All The Things You Are Jerome Kern Oscar Hammerstein 2nd 1940 Jazz Standard (Vintage sheet music) |

|

|

| All Time Standards (Songbook) Jazz Guitar Tablature Chord Melody Solos (Jeff Arnold) |

|

All Time Standards (Songbook) Jazz Guitar Tablature Chord Melody Solos (Jeff Arnold) |

| All Time Standards Piano (Arr. Gabriel Bock) |

|

All Time Standards Piano (Arr. Gabriel Bock) |

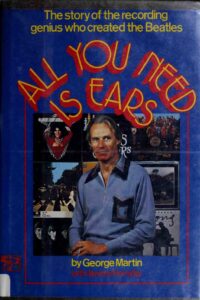

| All You Need Is Ears George Martin with Jeremy Hornsby 1979 (Book) The story o the recording genius who created The Beatles |

|

|

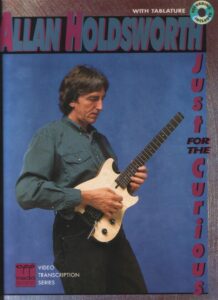

| Allan Holdsworth Just for the curious book Guitar with Tablature |

|

|

| Allan Holdsworth Melody Chords For Guitar |

|

|

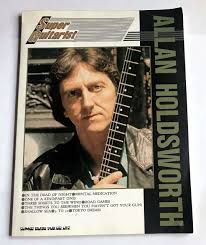

| Allan Holdsworth Super Guitarist with TABs |

|

Allan Holdsworth Super Guitarist with TABs |

| Alle prese con una verde Milonga (Paolo Conte) | ||

| Allevi, Giovanni – Back To Life |

|

|

| Allie Wrubel – Gone with the Wind |

|

|

| Allman Brothers Guitar Songbook |

|

Allman Brothers Guitar Songbook |

| Allman Brothers, Best Of The (Piano, Vocal, Guitar) |

|

Allman Brothers, Best Of The (Piano, Vocal, Guitar) |

| Allman Brothers, The – The Definitive Collection For Guitar Vol 1 with Tablature |

|

Allman Brothers, The – The Definitive Collection For Guitar Vol 1 |

| Alma Redemptoris Mater |

|

|

| Almeno tu nell’universo (Mia Martini) | ||

| Almir Chediak Ivan Lins Guitar Songbook Vol 2 |

|

Ivan Lins Guitar Songbook Vol 1 by Almir Chediak |

| Alok – Hear Me Now Sheet Music |

|

|

| Alone together (Howard Dietz & Arthur Schwartz) | Alone together (Howard Dietz Arthur SchwArtz) | |

| Alone Together (Musescore File).mscz | ||

| Alone Togheter Guitar Solo Transcription Jazz Standard |

|

|

| Alphaville Forever Young (piano & Guitar) |

|

Alphaville Forever Young (piano & Guitar) |

| Also Sprach Zarathustra Op. 30 – Richard Strauss (Musescore File).mscz | ||

| Alternative Rock Sheet Music Collection |

|

Alternative Rock Sheet Music Collection |

| Always on my mind – Elvis Presley – easy arrangement for piano, with fingering |

|

|

| Amadeus – W.A. Mozart (film score arr. for piano solo by D. Fox) |

|

Amadeus – W.A.Mozart |

| Amadeus (original soundtrack piano solo arrangements) |

|

Amadeus (Film score book) Piano Solos |

| Amalia Rodriguez FADOS Melodias De Sempre (GUITAR) |

|

Amalia Rodriguez FADOS Melodias De Sempre (GUITAR) |

| Amando amando (Renato Zero) | ||

| Amar Pelos Dois (Salvador Sobral) | ||

| Amarcord (Nino Rota) | ||

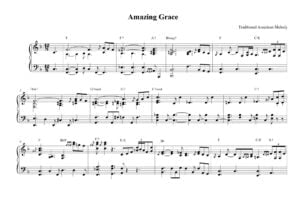

| Amazing Grace – Tradicional (Piano ) |

|

|

| Amazing Grace Traditional (Jazzy ver. sheet music) |

|

|

| Amazing Phrasing – Guitar 50 Ways to Improve Your Improvisational Skills (Guitar TABs Amazing Phrasing) (Tom Kolb) |

|

Amazing Phrasing – Guitar 50 Ways to Improve Your Improvisational Skills (Guitar TABs Amazing Phrasing) (Tom Kolb) |

| Amelie Poulain – 6 pieces for piano – Yann Tiersen – Yann Tiersen |

|

|

| America (My Country ‘Tis of Thee Easy Piano Level 2 |

|

|

| America Greatest Hits Piano Vocal Guitar chords |

|

America Greatest Hits Piano Vocal Guitar chords |

| America Greatest Hits (piano & Guitar) |

|

America greatest |

| America Horse With No Name Piano vocal | America Horse With No Name Piano vocal | |

| America’s Songs The Stories Behind The Songs Of Broadway, Hollywood, And Tin Pan Alley (Philip Furia, Michael Lasser) Book |

|

|

| American Folk Songs For Guitar with Tablature |

|

American Folk songs |

| American Folk Songs, My First Book of – Bergerac |

|

|

| American Indian Melodies A. Farwell Op.11 (1901) |

|

American Indian Melodies A. Farwell Op.11-min |

| American Pie (sheet music) |

|

|

| American Popular Music (Book) by Larry Starr and Christopher Waterman |

|

|

| Americana – Alegre, Magín (Guitarra) | Americana – Alegre, Magín (Guitarra) | |

| Amici Miei (Carlo Rustichelli) | ||

| Amor mio (Battisti) | ||

| Amore bello (Claudio Baglioni) | ||

| Amy Beach – Op.15 Four Sketches in Autumn |

|

|

| Amy Grant – Breath Of Heaven | ||

| Amy MacDonald This Is The Life |

|

AMY MACDONLAD |

| Amy Winehouse – Valerie |

|

|

| Amy Winehouse – Valerie (sheet music) |

|

|

| Amy Winehouse Amy Amy Amy |

|

|

| Amy Winehouse Back To Black Songbook |

|

Amy Winehouse Back To Black Songbook |

| Amy Winehouse Frank Songbook |

|

Amy Winehouse Frank |

| Amy Winehouse I Heard Love Is Blind |

|

|

| Amy Winehouse Just Friends |

|

|

| Amy Winehouse Rehab |

|

|

| Amy Winehouse You Know Im No Good |

|

|

| An affair to remember (Harry Warren) | ||

| An American In Paris An George Gershwin (Concert Band)An American In Paris An George Gershwin (Concert Band) Arr. by Naohiro Iwai |

|

|

| An American Tail – The Marketplace – James Horner | ||

| An Introduction To Bach Studies (eBook) |

|

|

| An Irish Blessing (Musescore File).mscz | ||

| An Irish Blessing (SATB) Choral | An Irish Blessing (SATB) | |

| Analisis musical claves para entender e interpretar la Música (M. y A. Lorenzo) Español |

|

|

| Analysis Of Tonal Music An Schenkerian Approach Allen Cadwallader and David Gagné (Book) |

|

|

| Analyzing Bach Cantatas by Eric Chafe (eBook) |

|

|

| Analyzing Schubert by Suzannah Clark (Cambridge Un. Press) (eBook) |

|

|

| Anastacia Not That Kind Songbook |

|

Anastacia songbook |

| Anastasia Once Upon A December arr. by John Brimhall (Piano Solo 2 Versions Easy And Intermediate) |

|

|

| Anastasia Sheet Music songbook Piano & vocal |

|

Anastasia Sheet Music songbook Piano & vocal |

| Ancora ancora ancora (Mina) | ||

| Ancora qui (Django Unchained) Elisa – Ennio Morricone | ||

| And the Waltz goes on (Anthony Hopkins) | ||

| Andante (from String Quartet op. 22) P. I. Tchaikovsky | ||

| Anderson Freire – So Voce Piano |

|

|

| Andras Schiff – Music Comes Out Of Silence Book |

|

|

| Andre Gagnon – L’air Du Soir |

|

|

| Andre Gagnon – Le Reve De L’automne (sheet music Collection) |

|

Andre Gagnon – Le Reve De L’automne (sheet music Collection) |

| Andre Gagnon – Les Jours Tranquilles | Andre Gagnon – Les Jours Tranquilles | |

| Andre Gagnon – Meguriai |

|

|

| Andre Gagnon – Nelligan |

|

|

| Andre Gagnon – Petite Nostalgie |

|

|

| Andre Gagnon – Reves D’Automne | Andre Gagnon – Reves D’Automne | |

| Andre Gagnon – The Very Best Of Andre Gagnon (Sheet Music Songbook) |

|

Andre Gagnon – The Very Best Of Andre Gagnon (Sheet Music Songbook) |

| Andre Gagnon Ciel D’Hiver |

|

|

| Andre Gagnon Entre Le Boeuf et l’Ane Gris Musique Traditionelle |

|

|

| André Gagnon L’air Du Soir |

|

|

| Andre Gagnon Neiges |

|

|

| André Gagnon Nelligan |

|

|

| André Gagnon Origami |

|

|

| André Gagnon Pensées Fugitives |

|

|

| Andre Gagnon Pensées Fugitives |

|

|

| André Gagnon Piano Solitude |

|

Gagnon, André Piano Solitude |

| Andre Gagnon Prologue |

|

|

| André Gagnon Selection Speciale de chansons (partitions musicales) |

|

André Gagnon Selection Speciale de chansons (partitions musicales) |

| André Gagnon Un Piano Sur La Mer (Piano Solo Partition Sheet Music) | Gagnon André Un Piano Sur La Mer (Piano Solo Partition Sheet Music) | |

| Andre Popp Paul Mauriat Love Is Blue Piano Solo Arr. |

|

|

| André Previn – Play Like André Previn no. 1 |

|

Andre Previn sheet music |

| Andre Previn – The Genius of (Piano Solos sheet music) |

|

The genius of André Previn |

| Andre Rieu La Vie Est Belle (Songbook Collection As Performed By André Rieu) |

|

Andre Rieu La Vie Est Belle (Songbook Collection As Performed By André Rieu) |

| Andrea Bocceli – Time To Say Goodbye | ||

| Andrea Boccelli – Time To Say Goodbye |

|

|

| Andrea Bocelli Romanza songbook (Guitar & Voice) |

|

Andrea Bocelli Romanza songbook |

| Andrea Bocelli – Anthology (songbook) |

|

|

| Andrea Bocelli – Con te partiro (Time to say Goodbye) Piano Solo arr | Andrea Bocelli – Con te partiro (Time to say Goodbye) Piano Solo | |

| Andrea Bocelli – Con te partiro (Time to say Goodbye) Piano Solo.mscz | ||

| Andrea Bocelli – The Best Of Songbook |

|

Andrea Bocelli best of |

| Andrea Bocelli Celine Dion The Prayer Easy Piano And Vocal By David Foster, Carole Bayer Sager, Alberto Testa And Tony Renis |

|

|

| Andrea Bocelli Celine Dion – The Prayer – Easy Piano and Vocal by David Foster, Carole Bayer Sager, Alberto Testa and Tony Renis.mscz | ||

| Andrea Bocelli Cieli Di Toscana (Piano, guitar & Vocal) |

|

Andrea Bocelli Cieli Di Toscana |

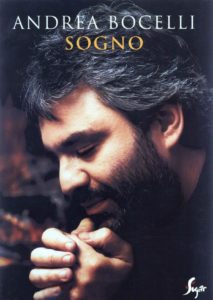

| Andrea Bocelli Sogno Songbook |

|

Andrea Bocelli sogno |

| Andrea Bocelli The Prayer |

|