Come join us now, and enjoy playing your beloved music and browse through great scores of every level and styles!

Can’t find the songbook you’re looking for? Please, email us at: sheetmusiclibrarypdf@gmail.com We’d like to help you!

Table of Contents

Kenny Barron – New York Attitude (1984) Jazz

Please, subscribe to our Library.

If you are already a subscriber, please, check our NEW SCORES’ page every month for new sheet music. THANK YOU!

Tracks:

1 New York Attitude 00:00 2 Embraceable You, Take 2 06:00 3 Joanne Julia 11:51 4 My One Sin 17:31 5 Bemsha Swing 22:56 6 Autumn In New York 29:49 7 Lemuria 37:51 8 You Don’t Know What Love Is 43:03 9 Embraceable You, Take 1 49:32

Credits: Bass – Rufus Reid Drums – Frederick Waits Piano – Kenny Barron Recorded December 14, 1984 at Van Gelder Recording Studios, Englewood Cliffs, N.J.

Kenny Barron. “The poetry of the piano” (Jazz)

For a jazz pianist, facing the piano face to face is an intense exercise in reflection, a reckoning with his baggage in music, a profound internalization process and, above all, a conversation with himself or Conversations with Myself (Verve, 1963), the famous album by Bill Evans, the jazz impressionist, an experience that he would repeat on albums such as Further Conversations with Myself (Verve, 1967), Alone (Verve, 1968), Alone Again (Fantasy, 1975) or New Conversations (Warner, 1978).

Keith Jarrett, a great fan of this kind of face to face with the piano to the point that it could be said that it was his usual mode of expression, has left us excellent albums, among others, The Köln Concert (ECM, 1975), the monumental Sun Bear Concert (ECM, 1978) or the recent Budapest Concert (ECM, 2020) recorded in 2016.

But this tour de force in front of the piano has a rich tradition in the history of jazz and all the great pianists walked this solitary path that allows an inner exploration with infinite possibilities, a continuous process of improvisation in which the usual question / answer happens in the limitless imagination of the musician.

Best Sheet Music download from our Library.

Just a few examples of pianists who throughout the history of jazz plunged into the creative solitude of the solo piano. The recognized virtuoso and master of all those who came after Art Tatum in the compilation Piano Solo (Capitol, 1972) that includes various sessions from 1949 —memorable version of Dvořák’s “Humoresque”—or in the series The Tatun Solo Masterpieces Vol 1 (Pablo , 1953). He also did numerous takes on the great Fats Waller collected on the Fats Waller Memorial 5 Lps Casket (RCA Victor, 1969).

Bud Powell, seminal foundation of bebop and modern jazz on numerous tracks on The Genius of Bud Powell (Mercury, 1956). Another of the basic pillars of modernity like Thelonious Monk in albums like Solo Monk (Columbia, 1965) or Piano Solo (Vogue, 1954).

Mainstream pianists ( also wanted to confront themselves in solo dialogue: Mal Waldron — Searching in Grenoble: The 1978 Solo Piano Tompkins Square, 2022) or All Alone (GTA Records, 1966) —, the elegant and lyrical Tommy Flanagan — Solo Piano (Storyville, 1974) or In His Own Sweet Time (Enja, 2020) recording rescued from a concert at the German town of Neubur in 1994; Kenny Drew, Everything I Love. Solo Piano (SteepleChase, 1973); Ray Bryant, Alone with the Blues (New Jazz, 1958); Errol Garner in the series for Decca, Errol Garner playing Piano Solos or Hank Jones, Have You Met Hank Jones (Savoy, 1956) are just a few examples.

But also contemporary pianists like Paul Bley, Solo Piano (SteepleChase, 1988); Fred Hersch —the triple album Songs without Words (Nonesuch, 2001) and Solo Piano (Palmeto, 2015)—; Brad Mehldau, Solo piano. Live in Tokyo (Nonesuch, 2004); Marc Copland, John (Illusions Mirage, 2020), tribute to guitarist John Abercrombie who died during the pandemic or the historic German pianist Joachim Kühn, Touch the Light (ACT, 2021) reviewed his jazz musical influences but also classical and pop music and nationally pianists such as Tete Montoliou, Solo piano (Timeless, 1989) compilation of the albums Y yellow Dolphin Street (1977) and Catalonian Folksongs (1978) or the young and versatile Marco Mezquida, La hora fertile (Whatabout Music, 2013), among many others.

And the great Barry Harris, custodian and champion of the bop tradition, could not be missing from this brief account —some consider it a kind of compendium of three of the most influential representatives of modern jazz: Parker, Monk and Powell and a renowned educator of jazz. so many talents that in albums like Listen to Barry Harris: Solo Piano (Riverside, 1961) or the most recent Solo (September, 1990) recorded in the Dutch Studio 44 and in which he makes an extensive tour of the modern jazz tradition through 15 songs, three originals (That Secret Place, So Far, So Good and Tribute to the Duke), readings by Monk (Monks Mood, Ruby my Dear and Blue Monk), by Powell (Hallucinations) and well-known classics by Rodgers, Youmans, Kern or Noble.

Harris precisely quoted Kenny Barron when asked about a young pianist he liked, they insisted on being young and reiterated, “Barron, of course!” Finding out soon after, Kenny was pleased that he will think of him as a young pianist, “even though I’m my years now, even though Barry is a lot older than me.”

Together they led the great album Confirmation (Candid, 1992) as a quartet with Ray Drummond and Ben Riley in the rhythm section, a gathering of teachers recorded at the Riverside Park Arts Festival on September 1, 1991.

Facing the piano alone could well be that feeling of “feeling that you are in the zone , a special place where everything works, heart, mind and technique”, as Fred Hersch wrote in the Solo album liner notes .

And, of course, Kenny Barron wanted and knew how to sink in front of the lacquered mirror of the piano, with all the respect that a dialogue of such magnitude implies:

«The solo piano has always scared me. That is number one. But the only way to deal with it is to deal with it, you know! […] It’s an opportunity for me to challenge myself at every concert and, at the same time, be aware that I’m not Art Tatum. Because sometimes that’s in the back of your mind. At the human level. Maybe I’m not doing enough. Maybe I’m not bright enough.

That’s still on your mind. So I’m trying to get to the point where that’s like a noise I can forget about. Don’t even worry about it. Worrying about that kind of thing, or how to stop worrying about it. But then again, the only way to stop worrying about it is to face it all the time. Just tell my story, whatever it is. And I think people respond, if you’re honest.” Interview by Peter Hum, Ottawa Citizen (06.20.2017)

An impressive number of recorded albums —“about 500 as accompanist, or maybe 400”, he once said, and fifty as leader or co-leader—… and yet it is surprising that he has only recorded two solo piano and forty years apart. The first, At the Piano (Xanadu, 1982), includes an excellent mixture of jazz classics and originals that, then, when he was in his forties, were part of his musical spirit baggage.

Seven songs for his solo piano debut, three of his own —“Bud-Like” as a tribute to the seminal Bud Powell, the rapturous “Calypso”, perhaps a Rollian wink and a memorable “Enchanted Flower”— and the rest are a must. Fulfillment for any pianist, the timeless ballad “Body and Soul”, the necessary Ellington-Strayhorn path in “The Star-Crossed Lovers” and, of course, Monk, another of his great influences: “Misterioso” and “Rhythm-a-Ning”. ”. High point, then, in his recording career, Robert Taylor pointed out in Allmusic .

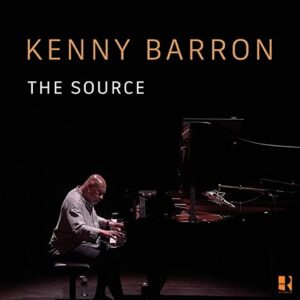

Now, at eighty and forty years later and, perhaps, in a sort of reckoning or testimonial legacy, The Source (Artwork, 2023) leaves us, recorded in July 2022 at the Theater de L’Athénée Lousi Jovert from Paris. As in At the Piano, it includes well-known own compositions —“What If”, “Dolores Street”, “Sunshower” and “Phantoms”), readings by Monk (“Teo”, “Well You Needn’t”), revisits the Ellington-Strayhorn duo (“Isfahan,” “Daydream”) and a Great American Songbook classic (“I’m Confessin’”).

On both albums, Barron establishes a lively connection with the listener to offer a musical discourse that is not forced, oblivious to any sense of pretense, in order to navigate various stylistic currents with the utmost elegance and virtuosity —from straight ahead jazz, classics, blues , bossa nova and even free improvisation—which attest to why he is considered one of the masters of jazz in history. “Album that could have been titled Kenny Barron: All The Things You Are “, Ed Enright has written in Downbeat (January 2023)… Indeed, everything that is.

A long and intense journey: musical biography

Eighty years old is Kenny Barron (Philadelphia, Pennsylvania, 1943). He began playing the piano at the age of six — “it was compulsory at home and my mother made me study classical piano until I was 16” — among his teachers, Vera, the sister of Ray Bryant, also a pianist and a native of Philadelphia, a prodigal city in jazzmen : Benny Golson, Tommy Bryant, Philly Joe Jones, Bobby Timmons, Archie Shepp, Lee Morgan, Hank Mobley, among others. See the good ear or that he was good at it…

«I became interested in jazz thanks to my brother Bill, a saxophonist, who had records by Charlie Parker, Dizzy, Dexter Gordon… And in Philadelphia there was also a 24-hour jazz station. My brother took me to my first concert with his band when he was 14 [with Mel Levin’s local band] and we played standards and pieces from the big bands. Then I moved to New York in 1961, which was a fantastic place at the time. That’s how it all started.”

While still in high school he worked with drummer Philly Joe Jones. And at the age of 19 he moved to New York starting a dizzying career as a freelance , accompanying musicians such as drummer Roy Haynes, trumpeter Lee Morgan or flutist and tenor sax player James Moody, after he heard him play at the Five Spot. Requested musician condition that he attributes:

«They call me because I can play well, empathy and the interpretation that one makes of the musical intentions of others also influences, I try to make everything easy, or so I think»

Key to his career was his entry in 1962 into trumpeter Dizzy Gillespie’s band on the recommendation of James Moody and without Dizzy hearing him play a single note. With Dizzy, in whose group he spent four years, he absorbed and developed a great knowledge and experience of the jazz language as well as an appreciation for Latin and Caribbean rhythms that he would later reflect on albums like Sambao or Canta Brasil .

«I joined his band at the age of 19, what am I going to say, he was a great human being and one of the greatest learning experiences I have had […]. Foremost, Dizzy was very easy to get along with. He wasn’t a dictatorial boss type, just a really nice guy. And he was very generous with his knowledge. He knew a lot about chords and harmony, and he was very generous. He always shared. ‘Why don’t you try expressing this chord this way?’

He taught me things on the piano. And some nights, if the last set wasn’t full, he’d get me off the piano and play a song or two with Moody. He wasn’t a great soloist, but he did know the voices and things like that. And he also knew a lot about rhythms, especially Brazilian rhythms and Latin rhythms, and where they came from. What region of Cuba or what region of Brazil. And also nonmusical things about how to treat people. He always treated people with the utmost respect. In the four years that I was with him, I never saw him get angry.

After leaving Gillespie’s band, he worked with Freddie Hubbard, Stanley Turrentine, Milt Jackson and Buddy Rich. In the early 1970s, Kenny worked with the great saxophonist Yusef Lateef, whom Kenny credits as a key influence on his improvisational art. I knew Lateef from before, when he was still living in Philadelphia and with whom he had just finished high school, he played several concerts and contributed, not as a performer but as a composer and arranger, to their album The Centaur and the Phoenix (Riverside, 1960) with the original “Revelation” and an arrangement of the standard “Ev’ry Day (I Fall in Love)”.

It was Lateef who encouraged him to combine touring with a college education, earning a degree in music from Empire State College (New York). This is how Kenny spoke of Lateef:

“He was honest. When he said something, you could believe it. Musically, it was open and very liberating. He was not specific with the instructions. Just be on time and no drugs.”

His recording debut took place with the album The Tenor Styling of Bill Barron (Savoy, 1961) directed by his brother Bill and which included also with the trumpeter Ted Carson, the bassist Jimmy Garrison and the drummer Frankie Dunlop who was followed by others along with his brother such as Modern Windows or Hot Line . About his brother (1927-1989):

«My brother and I used to talk about music. He wasn’t a pianist, so he couldn’t teach me piano. But we talk a lot about music. We talked about some of the concepts of him and who he liked. He leaned a bit more to the left , in the sense that he liked Cecil Taylor, classical composers like Webern and Stockhausen. So he was into some experimental stuff. That was his musical inclination ».

A year of great independent recording activity was 1967. He co-directed the album You Had Better Listen with trumpeter Jimmy Owens and participated in recordings with trumpeter Freddie Hubbard and saxophonists Joe Henderson, Stanley Turrentine, Tyrone Washington, Booker Ervin and Eric Kloss.

His ever-expanding discography continued to expand into the ’70s, featuring sessions with saxophonists and flutists such as Moody and Lateef, bassists Ron Carter and Buster Williams as well as musicians such as Carl Grubbs, Marion Brown and Marvin ‘Hannibal’ Peterson. Throughout the 1970s he continued to work regularly with prominent musicians, broadening the stylistic range of his collaborations—Stan Getz, Chico Freeman, violinist John Blake, trombonist and singer Ray Anderson, and drummer Elvin Jones.

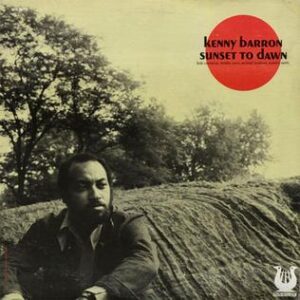

It was also the decade that marked the beginning of his career as a leader. Sunset to Dawn (Muse, 1973) their album His debut as a leader featured, among others, bassist Bob Cranshaw and drummer Freddie Waits and his own compositions such as “Sunset” or “Dolores Street”.

It was followed by albums such as Peruvian Blue (Muse, 1974), Lucifer (Muse, 1975), Innocence (Wolf Records, 1978) or Togheter (Denon, 1979) in a duet with pianist Tommy Flanagan and in which both maestros interpret six jazz classics. with a language loaded with swing and moments of improvisational brilliance. For Kenny Barron, Tommy Flanagan (1930-2001) was one of his great influences:

“My biggest influence was actually Tommy Flanagan, who I first heard during high school on a recording. What got me about Tommy was his touch and his lyricism, those two things. He had this very light, delicate touch, and when he touched it it was very, very logical. It was like speaking in sentences, with punctuation and all. That was my biggest influence. And then I discovered the influence of him, Hank Jones. So that particular style, that’s what got me.”

During the eighties he maintained his intense activity, touring and collaborating with other musicians and publishing twenty albums in various formats, among others, his first recording on solo piano — At the Piano (Xanadu, 1982) —; a duet with bassist Buster Williams — Two As One. Live at Umbria Jazz (Red Record, 1987) and with Red Mitchell — The Red Barron Duo (Storyville, 1988)—

Also a duo but alternating on double bass Ron Carter and Michael Moore — 1+1+1 (Blackhawk Records, 1986); a trio in Autumn in New York (Uptown, 1985) with Rufus Reid and Frederick Waits; in Scratch (Enja, 1985) with Dave Holland and Daniel Humair or in Landscape (Baystate, 1985) with Cecil McBee and Al Foster.

In the excellent Whatat If? (Enja, 1986) he performed as a quintet with trumpeter Wallace Roney, tenor sax player John Stubblefield, and Cecil McBee and Victor Lewis in the rhythm section including originals like “Phantoms,” “What If?” or “Voyage.”

He also founded the Sphere quartet with tenor saxophone Charlie Rouse, Buster Williams and Ben Riley, whose objective was to celebrate the music of Thelonius Monk and which remained active until Rouse’s death in 1988, publishing albums such as Four in One (Elektra , 1982 ), whose recording coincided by chance with the day of Monk’s death and therefore was not planned as a commemorative tribute and in which they perform outstanding readings of Monk’s classics.

It was followed by albums in which, although they do not cover Monk, their spirit is present, such as Flight Path , Sphere on Tour, Pumpkin’s Delight , Four for All and Bird Songs released the same year as Charlie Rouse’s death. The group met again with the alto sax Gary Bartz publishing the album Sphere (Verve, 1997).

Parallel to his work as a leader, he collaborated as a guest on numerous albums such as the one led by saxophonists Fran Foster and Frank Wess Franklin Speaking (Concord Jazz, 1985); in the collective tribute to trumpeter Clifford Brown, Time Speaks (Timeless, 1985) with Benny Golson, Freddie Hubbard, Woody Shaw, Cecil McBee, and Ben Riley, as well as in Moon Alley (Criss Cross Jazz, 1986) with the quintet led by trumpeter Tom Harrell and who also had a young Kenny Garrett as a guest.

The nineties were equally fruitful in terms of concerts and tours as well as collaborations and recordings, recording thirty albums under his name or as co-leader for labels such as Verve, Reservoir, SteepleChase, Red, Candid, Concord or Enja.

In trio format is the brilliant The Only One (Reservoir, 1990) with Ray Drummond and Ben Riley and a masterful tour of jazz classics and two Barron originals: “The Only One” and “Dolores Street”.

Excellent is People Time (Verve, 1992) a duet with tenor saxophone Stan Getz, recorded live at the Café Monmartre in Copenhagen in March 1991, three months before Getz’s death. Double album that includes 14 songs with memorable piano-saxophone dialogues. Later, the complete sessions were published in a 7 CD box: People Time: The Complete Sessions (Sunnsyde, 2010). It is appropriate to remember Barron’s special empathy with Getz, with whom he had previously collaborated with his quartet on tours and albums such as Anniversary or Serenit :

“Working with Stan Getz was also a great experience. We were sort of soul mates in the sense that we both liked lyricism and beauty. He had that sound that made you cry, especially when he played a ballad. We were on the same wavelength, I think.”

In Sambao (Verve, 1992) he brought together drummer Victor Lewis with Brazilian musicians —guitarist Toninho Horta, bassist Nico Assumpçao and percussionist Mino Cinelu— to pay homage to Brazilian rhythms through eight original compositions

In Other Places (Verve, 1993) together with Bobby Hutcherson, Ralph Moore, Rufus Reid, Victor Lewis and Minu Cinelu, he includes originals such as “Anywhere”, “Other Places”, “Mythology”, “Ambrosia” or “Nikara’s Song”.

Wanton Spirit (Verve, 1994), a trio with Charlie Haden and Roy Haynes —which he considers one of his favorites— and nominated for a Grammy for best jazz instrumental performance, is a sign of maturity.

Critic Lee Bloom in his review for Allmusic noted: “Early influences from Tatum, Powell, Monk, plus Tommy Flanagan’s melody lines, McCoy Tyner’s pentatonic harmony and Herbie Hancock’s flowing rhythm have been completely absorbed by Barron. ».

Some recordings from this period are Things Unseen (Verve, 1997) in which he includes 8 of his own compositions, leading a band made up of John Scofield, John Stubblefield, Eddie Henderson, David Williams, Victor Lewis, Mino Cinelu and the Japanese violinist Naoko Terai. Together Again from the First Time (Red Records, 1997) is a collective album of great figures brought together by the Italian label: Jerry Bergonzi, Bobby Watson, Kenny Barron, Curtis Lundy, David Fink and Victor Lewis.

In The Artistry of Kenny Barron (Wave, 1998) with bassist Peter Ind and drummer Mark Taylor includes lively readings of jazz classics like Body and Soul or Lover Man and Monk originals (Rhythm-a.Ning, Well You Needn’ t).

Night and the City (Verve, 1998), recorded live at New York’s Iridium in September 1997, is an intense and reflective musical dialogue between Barron and bassist Charlie Haden that at times becomes disturbing through classics and originals by both.

Already established as a reference point for jazz piano, he faced the new century with renewed creative energy, alternating his work between tours and concerts, recordings and teaching work: in the year 2000 he left his position at Rutgers University, which he had held since 1974, to join the Julliard School of Music.

In his recordings, he alternates sessions as a duo or trio and with more extensive formations such as in Spirit Song (Verve, 2000), nominated for a Grammy and in which he appears as a septet with the trumpeter Eddie Harris, the tenor saxophone David Sánchez, the guitarist Russell Malone and in the rhythmic section Rufus Reid and Billy Hart and as a guest the young violinist Regina Carter.

And with Regina Carter he recorded a duet Freefall (Verve, 2001), a solid dialogue from which a coherent and joyous musical creativity springs. With Canta Brasil (Sunnsyde, 2002) he returns to Brazilian rhythms in the company of the Trio da Paz with originals like “Zumbi”, “Clouds” or “Thoughts and Dreams”.

Return to the quintet format with Images (Sunnsyde, 2004) now with vibraphone (Stefon Harris) and flute (Anne Drummond), an association that generates attractive and sweet music without falling into cloying and with a superb Barron both as interpreter and composer for the originals he contributes: “Images”, “So It Seems”, “Jasmine Flower! or “Inside Out”.

Back as a trio, in Superstandards (Venus, 2004) with bassist Jay Leonhart and drummer Al Foster, it is a brilliant exercise in reading traditional jazz classics but also modern jazz with originals by Rollins (“Doxy”) or Oliver Nelson. (“Stolen Moments”)

Four years later he published The Traveler (Sunnsyde, 2008) for which he enriched the sound palette with the incorporation of the West African guitarist Lionelk Loueke, a change of musicians —the soprano saxophone Steve Wilson, the drummer Francisco Mela and the now regular double bassist Kiyoshi Kitagawa. — and on some of the tracks the voices of Ann Hampton Callaway, Grady Tate and Gretchen Parlato. Perfect portrait of his repertoire with originals like “The Traveler”, “Um Bejio” or “Illusions” and, as always, Barron with his distinctive style full of swing and empathy.

With Minor Blues (Venus, 2009), he returned to the expressive trio format with George Mraz and Ben Riley, a journey through classics by Mercer, Young, Mandel or Berlin, an impressive reading of “Don’t Explain” by Billie Holiday and his original “Minor Blues” and an excellent example of his improvisational skills in a small setting.

As a duo, they released several albums with outstanding musicians of different instruments, with double bassists Harvie S [Swartz] — Now Was the Time (Savant, 2008) and Witchcraft (Savant, 2013). With Dave Holland The Art of Conversation (Impulse!, 2014), which, as the title suggests, is a demonstration of musical dialogue that illuminates the listener through a repertoire that is half classic, half original by both interpreted with profound mastery, great rapport and expressiveness elegant and sober.

As a duet but with the vibraphonist Mark Sherman he published the suggestive Interplay (Chesky, 2015) and with the alto saxophone George Robert two albums in 2014 The Good Life and Coming Home .

Masterful is the piano dialogue maintained by Kenny Barron and Mulgrew Miller (died 2013) throughout three concerts held in 2005 (Marciac, France) and 2011 (Geneva and Zurich, Switzerland) and collected on the triple album entitled The Art of Piano Duo (Groovin’ High, 2019). The repertoire is an exhaustive sample of the range of the jazz canon.

Themes from the great American songbook, by famous composers such as Rogers, Hart, Jimmy Van Heusen or Johnny Burke, together with pieces by jazz legends such as Duke Ellington, Charlie Parker and, as always, the great Thelonious Monk. An admirable display of creative wisdom by two of the most outstanding pianists in the history of jazz.

Once again, he met as a trio on albums such as Thrasher Dream Trio (Whailing City Sound, 2013) led by double bassist Ron Carter and drummer Gerry Gibbs. Then together with bassist Kiyoshi Kitagawa and drummer Johnathan Blake on Book of Intuition (Impulse!, 2016), nominated for a Grammy for best instrumental album, in which it is the first record with the trio that he has led for the last decade and an example of his skill and skill in the difficult art of this format.

The album includes ten tracks, seven originals by Barron, two by Monk and one by bassist Charlie Haden. And also as a trio with Dave Holland and Johnathan Blake, he released Without Deception (Dare 2 Records, 2020) with a repertoire of originals by Barron and Holland, some classics and Monk’s unusual original “Worry Later”.

For Concentric Circles (Blur Note, 2018) he expanded the trio to a quintet by adding trumpeter Mike Rodríguez and saxophonist Dayna Stephens to his usual rhythm section (Kitagawa and Blake). The album includes eight originals, a Brazilian song and the Monkian reference “Reflections”. Music that borders on the borders of bop with traces of Afro-Latin and Brazilian rhythms, performed with his singular and distinctive elegance.

And among other collaborations, he put his piano on albums by vocalists such as Claire Martin —Too Much in Love to Care (2012)—, as well as on Patty Lomuscio’s second album Stars Crossed Lovers (Challenge, 2022), in which the alto saxophone Vincent Herring, bassist Peter Washington and drummer Joe Fansworth.

The Source (Artwork, 2023) solo piano, his recent album —commented on previously— can be considered a special celebration of his 80th birthday but above all a masterpiece and angular piece that closes the circle of a long and intense creative process.

A long and fruitful journey in search of his own path, which Kenny Barron himself defined in 2015 in an interview by Michael J. Westa for Jazz Times :

“I’m still looking for it! I’m serious! I’m closer, but I’m still trying to find it. Someone once said that music is a journey, and it’s an endless journey. And you never want to get there. If you arrive, it’s over.”

Process and learning journey of a teacher whose secret is apparently simple:

«I have always looked for better musicians than me, who have a high level, it is the best way to learn, and that is how I transmit it to my students, who look for motivating collaborations. I need to get out of the comfort zone and that’s the best way to do it, taking risks, and I’m still at it. 2021 interview by A. Naranjo for the Granada Hoy newspaper on the occasion of the Jazz festival in La Costa de Almuñécar.

A musical journey unanimously recognized both by the many musicians with whom he has collaborated and by cultural institutions and specialized critics: Jazz Master by the NEA (National Endowment For The Arts), member of the American Academy of Arts and Sciences, member American Jazz Hall of Fame inductee, Honorary Doctor of SUNY Empire State and Berklee College of Music, Living Legacy Mid-Atlantic Arts Foundation Award, MAC Lifetime Achievement Award.

He has received twelve Grammy Award nominations and has won critics’ and readers’ polls from prestigious publications such as DownBeat , Jazz Times and Jazziz . And he has received the award for Best Pianist from the Association of Jazz Journalists seven times, the last in 2017.

And a musical career that bears certain parallels with that of other great pianists, for example, Hank Jones or Tommy Flanagan: he has worked with many musicians and from different musical aesthetics, adapting in each case with proverbial ability.

In essence, and according to his own words, «basically, I am a bebop interpreter », a style that has been refined and matured since his initial influence from Bud Powell —he manifests himself in the original “Bud-Like” included in At the Piano (1982). , his first solo piano album but also with the lyricism and elegant touch of Tommy Flanagan and the taste for harmonies and abstractions of Thelonious Monk that would become a sort of personal hallmark.

Generous educator

Even before giving classes in a regulated way in prestigious centers, he served as a generous educator in the day-to-day life of his bands in which he welcomed young talents. A way of returning the opportunity that he had when James Moody recommended Dizzy Gillespie: «I like to do that when I listen to a young man who really knows how to play. Because someone gave me that opportunity when I was young. So if I can pay that payment back, I’d love to be able to do it.”

In 1974 he entered Rutgers University (New Jersey) as a professor of piano and harmony where he had current talents as students, among others, the trumpeter Terence Blanchard, the saxophonists David Sánchez and Harry Allen or the singer Regina Belle. At the end of 1999 he left Rutgers University and entered the School of Music of Manhattan where he had outstanding students such as pianists Aaron Parks and Gerald Clayton. He currently practices at New York’s Juilliard School, where he advises numerous musicians.

About the teaching system at Juilliard:

«What we did was play. We played standards, we played all kinds of repertoire, we played some of their music, because they brought original music. And for me, it was about listening to them and seeing what their weaknesses were. Was it his way of playing? Did they play too much? Were they lyrical? Those kinds of things. Just finesse. I couldn’t teach them to play, they already knew how to play. It was just finesse.” Peter Hum, Ottawa Citizen (06.20.2017)

| Artist or Composer / Score name | Cover | List of Contents |

|---|---|---|

| Gershwin – Summertime Piano Solo |

|

|

| Gershwin – Summertime (Musescore File).mscz | ||

| Gershwin – Summertime (original) | Gershwin – Summertime (original) | |

| Gershwin – Summertime (Solo by Miles Davis) | George Gershwin – Summertime (Solo – Miles Davis) | |

| Gershwin – That certain Feeling (sheet music) |

|

|

| Gershwin – The glory of Gershwin [piano vocal chords] |

|

Gershwin – The glory of Gershwin |

| Gershwin – The Greatest Songs Of George Gershwin |

|

George Gershwin – The Greatest Songs Of George Gershwin |

| Gershwin – The Man I Love (Piano) (Musescore File).mscz | ||

| Gershwin 12 Arrangements For Classic Guitar By John W Duarte |

|

Gershwin 12 Arrangements For Classic Guitar |

| Gershwin 3 Preludes for 2 pianos (four hands ) | Gershwin – Stone – 3 Preludes for 2 pianos four hands | |

| Gershwin A Foggy Day – Jazz Masters Play Gershwin(Guitar with Tablature) |

|

|

| Gershwin An American in Paris (transcription for piano solo) | Gershwin An american in Paris | |

| Gershwin Cole Porter Do_It_Again.mscz | ||

| Gershwin Do Do Do (Piano Solo) |

|

|

| Gershwin Experiment David Cope – Prelude | Gershwin Experiment David Cope Prelude | |

| Gershwin Guitar Songbook taught by Fred Sokolow with Tablature |

|

Gershwin Guitar Songbook taught by Fred Sokolow |

| Gershwin It ain’t necessarily so | ||

| Gershwin Jazz Interpretations |

|

Gershwin Jazz |

| Gershwin Jeff Manookian Concert Paraphrase on I love you Porgy | Gerswhin_Jeff Manookian Concert Paraphrase on I love you Porgy | |

| Gershwin Porgy And Bess Selection (Voice & Piano) |

|

Gershwin Porgy And Bess Selection (Voice & Piano) |

| Gershwin Rhapsody In Blue (Musescore File).mscz | ||

| Gershwin Rhapsody In Blue (Piano Solo Arr.) |

|

|

| Gershwin Songbook (Piano Solo) |

|

Gershwin–Songbook–Sheet music |

| Gershwin The Man I Love (piano solo) | ||

| Gershwin, George The Man I Love (Piano Solo Arr. By Percy Grainger) Sheet Music |

|

|

| Gershwin, George – Impromptu in Two Keys | Gershwin – Impromptu in two keys | |

| Gershwin, George I Got Rhythm Variations for piano and orchestra (Piano Score) |

|

|

| Gershwin, George works can be found in Jazz/Standards section and also in Musicals | ||

| Gershwin’s Melodies By Yuri Markin For 4 Hands Piano | Gershwin’s Melodies By Yuri Markin For 4 Hands Piano | |

| Get Back – John Lennon And McCartney Guitar Play Along | Get Back – Lennon And Mccartney Guitar Play Along Volume 25 with embedded audio MP3 | |

| Get Over It – Dream Of Me | ||

| Gettysburg – Dawn – Randy Edelman | ||

| Getz Gilberto – Corcovado quiet nights | Corcovado | |

| Getz Gilberto Stan Getz Joao Gilberto Featuring Antonio Carlos Jobim Guitar Tablature |

|

Getz Gilberto Stan Getz Joao Gilberto Featuring Antonio Carlos Jobim Guitar Tablature |

| GFTPM (Guitar Tab Songbook) Acoustic Classics (Tabs with Audio Mp3 Tracks Play Along)) | GFTPM – acoustic classics | |

| Ghibli Medley – Studio Ghibli film music arr. piano |

|

|

| GHOST Alex North Unchained Melody |

|

|

| Ghost The Musical |

|

Ghost The Musical |

| Giacomo Moroder Take My Breath Away From The Film Top Gun (Love Theme) Piano Vocal Chords | Giacomo Moroder Take My Breath Away From The Film Top Gun (Love Theme) Piano Vocal Chords | |

| Giacomo Puccini – O Mio Babbino Caro (Guitar arr. sheet music with TABs) | Giacomo Puccini – O Mio Babbino Caro (Guitar arr. sheet music with TABs) | |

| Giant Steps (Musescore File).mscz | ||

| Giant Steps Bebop And The Creators Of Modern Jazz 1945 65 (Book) By Kenny Mathieson |

|

|

| Giant The Musical Piano Vocal Score by Michael John Lachiusa |

|

Giant The Musical Piano Vocal Score by Michael John Lachiusa |

| Giants of Jazz Piano, The |

|

Giants of Jazz Piano The |

| Giazotto Albinoni Adagio (In G Minor) For Solo Piano |

|

|

| Gibran Alcocer Idea 1 | Gibran Alcocer Idea 1 | |

| Gibran Alcocer Idea 10 | Gibran Alcocer Idea 10 | |

| Gibran Alcocer Idea 15 | Gibran Alcocer Idea 15 | |

| Gibran Alcocer Idea 22 (Abridged) | Gibran Alcocer Idea 22 (Abridged) | |

| Gibran Alcocer Idea 7 | Gibran Alcocer Idea 7 | |

| Gibran Alcocer Idea 9 | Gibran Alcocer Idea 9 | |

| Gieseking, Walter & Karl Leimer – Piano Technique (Book) |

|

|

| Gil Evans Gone Full Score As recorded by the Miles Davis Gil Evans Orchestra |

|

|

| Gilbert Sullivan – It’s Easy To Play Gilbert Sullivan |

|

Gilbert & Sullivan – It’s Easy To Play Gilbert & Sullivan |

| Gilbert Bécaud Nathalie Piano Solo Guitar Chords | Gilbert Bécaud Nathalie Piano Solo Guitar Chords | |

| Gilbert Bécaud Quand Il Est Mort Le Poete | Gilbert Bécaud Quand Il Est Mort Le Poete | |

| Gilbert O’Sullivan – Greatest Hits (Songbook) |

|

Gilbert O’Sullivan – Greatest Hits (Songbook) |

| Gilberto Gil – Guitar Songbook vol 2 |

|

Gilberto Gil – Guitar Songbook vol 2 |

| Gilberto Gil vol 1 Guitar songbook |

|

Gilberto Gil – Guitar Songbook vol 2 |

| Giles Vigneault – Un Dimanche à Kyoto (Paroles et Musique) |

|

|

| Gillock , William Recital Collection (Intermediate to Advanced) |

|

Gillock , William Recital Collection (Intermediate to Advanced) |

| Gillock , William Accent On Gillock Vol. 1 Piano Solos |

|

|

| Gillock , William Accent On Gillock Vol. 2 Piano Solos |

|

|

| Gillock , William Accent On Gillock Vol. 3 Piano Solos |

|

|

| Gillock , William Accent On Gillock Vol. 4 Piano Solos |

|

|

| Gillock , William Accent On Gillock Vol. 5 Piano Solos |

|

|

| Gillock , William Accent On Gillock Vol. 6 Piano Solos |

|

|

| Gillock , William Accent On Gillock Vol. 7 Piano Solos |

|

|

| Gillock , William Accent On Gillock Vol. 8 Piano Solos |

|

|

| Gillock , William – Autumn Sketch Piano Solo |

|

|

| Gillock , William – Flamenco Piano Solo |

|

|

| Gillock , William – Holiday In Paris Piano Solo |

|

|

| Gillock , William Essential Collection |

|

|

| Gillock, William 24 Romantic Piano Solos in all Major and minor Keys |

|

Gillock, William 24 Romantic Pieces Lyric Preludes in Romantic Style |

| Gillock, William – New Orleans Nightfall Pano Solo |

|

|

| Gillock, William French Doll William Gillock Piano Solo |

|

|

| Gillock, William Happy Birthday To You Mid Intermediate Level Piano Solo arr. by William Gillock |

|

|

| Gillock, William Lyric Preludes In Romantic Style |

|

Gillock, William Lyric Preludes In Romantic Style |

| Gillock, William New Orleans Jazz Styles by William Gillock (piano) |

|

New Orleans Jazz styles |

| Gillock, William Valse Etude In Romantic Style Piano Solo |

|

|

| Ginastera-Tres Piezas 3 Criolla | ||

| Ginastera, Alberto Ginastera Tres Piezas Para Piano |

|

|

| Ginastera, Alberto Ginastera 12 American Preludes Doce Preludios Americanos | Ginastera, Alberto Ginastera 12 American Preludes Doce Preludios Americanos | |

| Ginastera, Alberto Ginastera Danzas Argentinas Opus 2 |

|

|

| Ginastera, Alberto Ginastera Milonga |

|

|

| Ginastera, Alberto Ginastera Suite De Dana Criollas Op 15 Ginastera |

|

|

| Ginastera, Alberto Sonata for guitar Op. 47 |

|

|

| Gino Paoli Il Cielo In Una Stanza (Mina) Piano Vocal Sheet Music | Gino Paoli Il Cielo In Una Stanza (Mina) Piano Vocal Sheet Music | |

| Gino Paoli In Un Caffé Piano Vocal Sheet Music | Gino Paoli In Un Caffé Piano Vocal Sheet Music | |

| Gino Paoli Sapore Di Sale Piano Vocal Sheet Music | Gino Paoli Sapore Di Sale Piano Vocal Sheet Music | |

| Gino Paoli Sassi Piano Vocal Sheet Music | Gino Paoli Sassi Piano Vocal Sheet Music | |

| Gino Paoli Senza Fine Piano Vocal Sheet music | Gino Paoli Senza Fine Piano Vocal Sheet music | |

| Gino Paoli Ti Lascio Una Canzone Piano Vocal Sheet music | Gino Paoli Ti Lascio Una Canzone Piano Vocal Sheet music | |

| Gino Paoli Una Stella Di Ghiacci Piano Vocal Sheet Music (Carla Boni) | Gino Paoli Una Stella Di Ghiacci Piano Vocal Sheet Music (Carla Boni) | |

| Gino Vannelli – Brother to Brother songbook |

|

Gino Vannelli – Brother to Brother songbook |

| Gino Vannelli Songbook Volume I Thirty Complete Scores |

|

Gino Vannelli Songbook Volume I Thirty Complete Scores |

| Giochi infantili (La Sconosciuta OST) Ennio Morricone | ||

| Giorgia Greatest Hits – guitar |

|

Giorgia Greatest Hits – guitar |

| Giorgio Moroder Midnight Express Love Theme | Giorgio Moroder Midnight Express Love Theme | |

| Giorgio Moroder Midnight Express Theme | Giorgio Moroder Midnight Express Theme | |

| Girl from Ipanema (Antonio Carlos Jobim) | ||

| Gismonti, Egberto – Complete songbook (piano vocal) |

|

Gismonti, Egberto – Songbook |

| Gismonti, Egberto – Sete Aneis (guitar) | Gismonti, Egberto – Sete Aneis (guitar) | |

| Giveon – Heartbreak Anniversary (Piano solo sheet music) |

|

|

| Giya Kancheli – When Almonds Blossomed |

|

|

| Glad Tidings Of Great Joy (Christmas Traditional) For Two Pianos Or Piano And Voices |

|

|

| Glad Tidings Of Great Joy (Musescore File).mscz | ||

| Glee (The Music) Showstoppers Songbook 3 |

|

Glee (The Music) Shwstoppers Songbook 3 |

| Glen Miller Joe Garland – In The Mood (Piano Solo arr.) | Glen Miller Joe Garland – In The Mood (Piano Solo arr.) | |

| Glen Miller Joe Garland – In The Mood (Piano Solo arr.).mscz | ||

| Glenn Meets Wolfgang (Music from Sonate facile Mozart) by Jef Penders |

|

|

| Glenn Miler – Bach A La Jazz | Glenn Miler – Bach A La Jazz | |

| Glenn Miller – Moonlight Serenade | Glenn Miller Moonlight Serenade Piano Vocal Guitar Chords | |

| Glenn Miller In The Mood Piano and vocal song by Joe Garland | Glenn Miller In The Mood Piano and vocal song by Joe Garland | |

| Glenn Miller Medley arr. by Naohiro Iwai |

|

|

| Glenn Miller Moonlight Serenade (Lead sheet) | Glenn Miller Moonlight Serenade | |

| Glenn Miller The Songbook Of Glenn Miller |

|

Glenn Miller The Songbook Of Glenn Miller 1904 – 1944 —  |

| Gli Insuperabili Gruppi Degli Anni 60 sheet music collection 0f the 60s |

|

Gli Insuperabili Gruppi Degli Anni 60 sheet music collection 0f the 60s |

| Glinka – The Lark from A Farewell to Saint Petersburg No. 10 (Piano Solo arr.) | Glinka – The Lark from A Farewell to Saint Petersburg No. 10 (Piano Solo arr.) | |

| Glinka – The Lark From A Farewell To Saint Petersburg No. 10 (Piano Solo Arr.) (Musescore File).mscz | ||

| Glinka Nocturne in Eb Major | Glinka_-_Nocturne_in_Eb_Major | |

| Glinka Nocturne La Séparation |

|

|

| Glinka Valse Fantaisie Original version for Piano (1839) |

|

|

| Gloria Estefan – Anything For You | ||

| Gloria Estefan – Everlasting Love | ||

| Gloria Estefan – I Will Survive | ||

| Gloria Estefan And Miami Sound Machine Best Of Piano Vocal Guitar chords |

|

Gloria Estefan And Miami Sound Machine Best Of Piano Vocal Guitar chords |

| Gloria Estefan Gloria Songbook Piano Vocal Guitar Chords |

|

Gloria Estefan Gloria Songbook Piano Vocal Guitar Chords |

| Gloria Gaynor – I Will Survive | ||

| Gluck Melody from Orfeo (piano arr. Sgambati) |

|

|

| Gluck Melody from Orfeo piano transcr. Siloti | ||

| Gluck Melody from Orpheus (arr. Bauer) | ||

| Gluck-Kempff – Ballet Music from ‘Orpheus und Euridike’ – Arr. Piano solo | ||

| Glück, das mir verblieb (Marietta’s Lied) |

|

|

| Gnattali, Radames – Concerto no. 4 arr. for guitar and piano |

|

|

| Go West – True Colors | ||

| Gocce di memoria (Giorgia) | ||

| God Bless America And Other Patriotic Favorites Alto Sax (Irving Berlin) |

|

God Bless America And Other Patriotic Favorites Alto Sax (Irving Berlin) |

| Godspell – Day By Day | ||

| GODSPELL – The Musical by Stephen Schwartz |

|

|

| Golden Scores Favorites Film Selections arr. by Phillip Keveren Piano Solo |

|

Golden Scores Favorites Film Selections arr. by Phillip Keveren Piano Solo |

| Golden Slumbers – Carry that Weight – The End (Beatles) | ||

| Golden Wind Main Piano Theme from Jojo’s Bizarrre Adventure |

|

|

| Gone 1926 Benny Davis And Joe Burke Jazz Standard (Vintage sheet music) |

|

|

| Gonzales – Chilly Gonzales Solo Piano II |

|

Gonzales – Chilly Gonzales Solo Piano II |

| Gonzales – Prelude To A Feud Chilly Gonzales |

|

|

| Gonzales The Tourist |

|

|

| Gonzales, Chilly – Solo Piano Vol 1 and 2 |

|

Gonzales, Chilly – Solo Piano Vol 1 and 2 |

| Goo Goo Dolls – Iris | ||

| Good enough (Evanescence) |